As far as sailing goes, it had been a summer of frustrations for me, with one boating trip after another canceled or cut short while I dealt with life ashore. A series of job interviews seemed to be heading nowhere I wanted to go. My house was an affliction of leaking faucets, sagging gutters, and wildly overgrown hedges, and the car wasn’t much better—wheel bearings, transmission, tires, all the tedious consequences of chronically unenthusiastic maintenance arriving all at once. Then an unexpected funeral brought me back early from a solo cruise on Georgian Bay. I kept hoping that one morning all these unwelcome obligations would drain away like an ebbing tide, leaving me free to hoist a sail and set out along the margins of the world to find a place where the water’s crooked fingers had dug deep into something worth seeing.

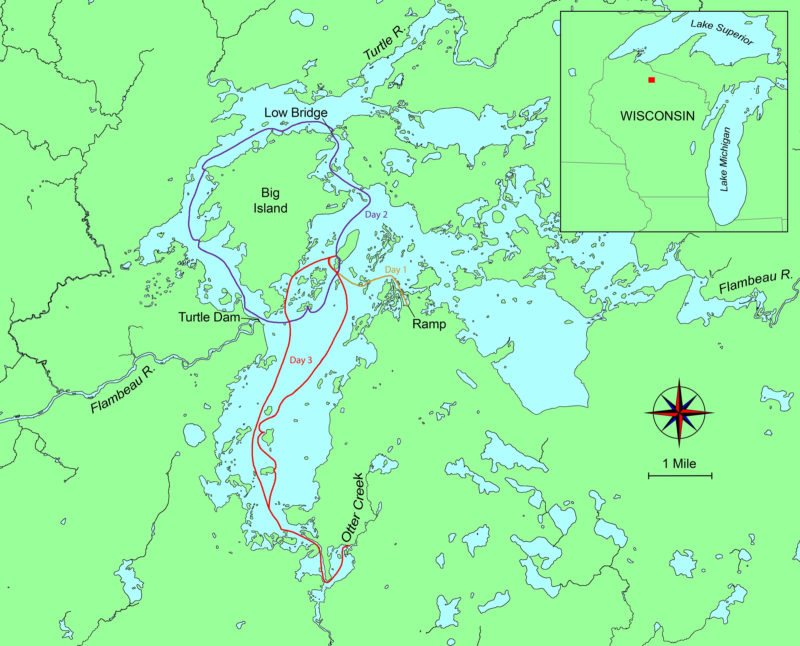

A cold and rainy September seemed likely to finish the dreary season entirely. But then a narrow window of freedom opened unexpectedly just as the weather promised to improve, and I was off with my boat and a pile of camping gear before complications could arise, with no clear destination in mind except “away.” A quick look at a rest-stop road map an hour down the road reminded me of a sprawling lake system in northern Wisconsin, 15 miles from the Michigan border, created by a dam at the confluence of the Turtle and Flambeau rivers. I hadn’t been there for a couple of years, which seemed like reason enough to make it my destination now. After a phone call to convince my brother Lance to meet me there with his Phoenix III for a few days, I was moving again. “The life of a wise man is most of all extemporaneous,” Thoreau assures his readers, and by this definition I am nothing if not wise.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

“Paul Bunyan was too busy a man to think about posterity,” wrote Aldo Leopold, noted conservationist and author of the classic A Sand County Almanac, “but if he had been asked to reserve a spot for posterity to see what the old north woods looked like, he likely would have chosen the Flambeau.” The ancient pine forests of northern Wisconsin were gone before the 20th century began, as Leopold knew all too well; his essay on the Flambeau River is in large part an elegy to a vanished world. By the time he wrote it, sometime in the 1940s, the Turtle-Flambeau Dam near the river’s headwaters was 20 years old. But despite the irresistible advance of modernization—Wisconsin’s burgeoning dairy industry needed such dams for rural electrification—the state government had also moved to preserve a 50-mile stretch of wild river on the upper Flambeau, just below the dam. Leopold again: “Slowly, patiently, and sometimes expensively the Conservation Department has been buying land, removing cottages, warding off unnecessary roads, and in general pushing the clock back, as far as possible, toward the original wilderness.” It was a wilderness that would later expand to include the new man-made lake that had swallowed the floodplains of the two rivers for a few miles above the dam.

As I pulled into the parking lot at the main boat ramp of the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage—all but empty on a Sunday evening in mid-September—it seemed to me that the clock had been pushed back far enough to seem almost irrelevant here. The lake lay hidden within a forest of pines and hardwoods already more than 100 years old. The shoreline wandered across the map in a series of elaborate flourishes for more than 100 miles, enclosing 14,000 acres of water and nearly 200 undeveloped islands—and, almost unbelievably, dozens of free first-come, first-served campsites accessible only by boat. Here was a sail-and-oar wilderness at the scale of a long weekend, along with an astonishing absence of bureaucracy. No fees, no permits, no reservations. The clock, it seemed, had not just been pushed back. In some ways it had stopped running entirely.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorJust minutes from the boat ramp, Lance and I were well on our way into the heart of the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage. Aboard the Alaska, the space between the forward thwart and the mast serves as the cargo hold, leaving the rest of the cockpit clear; storing most of the gear in two large duffel-style dry bags makes unloading simple when camping ashore.

Lance was already at the ramp when I arrived. We launched our boats, hastily transferred gear, parked our cars, and set off under oars down a narrow channel that ran northward between a chain of tiny islands to starboard and a long peninsula to port. When we reached open water, we hoisted our sails and began working our way southwest in light winds as the sun dropped toward the horizon. An hour later, we sailed into the wind shadow of an unnamed island—one of many—near the center of the flowage and turned north again, ghosting along in winds too light to feel. One of the unwritten rules of evening sailing was holding true: the closer we got to our destination, the fainter the breeze became. No matter, though. We were in no hurry. We simply glided along past island after island, moving so slowly that each boat seemed to be floating atop an impressionistic portrait of itself, Monet trading his lilies for lugsails.

We beached our boats below an empty campsite at the northern tip of an unnamed island and unloaded our gear. We had come only 2 miles from the ramp, but distance is not the only measure of solitude. There is magic to camping on an island, however near the mainland it might be—just ask Tom Sawyer or Huck Finn. Two miles on the map had become 100 miles in my mind, a welcome unburdening from life ashore.

Our campsite’s location near the center of the flowage offered a good view of Big Island to the northwest and opportunities for exploring in any direction, no matter what the wind decided to do that day.

Our island had been a low ridge on the east bank of the old Flambeau River before the dam swallowed it up. Now the river was gone, along with a dozen smaller lakes and waterways: Rat Lake, Horseshoe Lake, Townline Lake, Baraboo Lake, Otter Creek, Beaver Creek, and more. But other than the wide band of gravelly beach surrounding each island, the mark of midsummer drawdown at the dam, there was no obvious sign of the lake’s industrial origins. There were a few cabins and lodges along the northern and western sides of the flowage, I knew, but here we seemed surrounded by pure wilderness.

The boats rested in still water while we unloaded gear at camp. The Alaska’s boomless lugsail makes brailing a simple option for quick stops ashore, even without a dedicated brailing line.

After setting up our tents and cooking supper over camp stoves, too lazy to bother with a fire, we watched the moon climb through the treetops. The wind died away entirely as the evening grew darker. When the islands had faded to nothing but jagged silhouettes in the moonlight, I returned to the water’s edge to check on the boats before retreating to my tent for the night. But, as usual, the temptation was too much for me. Instead of going back to camp, I shoved off and set out under oars with no intention but to continue moving slowly through the night until I had seen something of what there was to see.

Working to an easy rhythm with the oars floating lightly in my hands, I glided over water so dark and still that it might have been a photograph. With each stroke, water ran down the oar blades to fall drop by drop onto the surface of the lake, and the sweep of the oars on the recovery drew long arcs of slowly expanding circles alongside the hull. It was the only sign that the boat was moving at all.

I kept rowing gently through a maze of islands that were nothing more than looming shadows in the darkness. For how long—an hour? Two? It was impossible to know. Somewhere out on the water a loon called, and called again. And far above the earth, beyond the darkness of the night sky, the stars continued their slow-moving circumnavigations around the pole star, measuring out the hours almost imperceptibly.

Morning brought an autumn chill and cloudy skies. We dawdled through an unambitious breakfast in camp, waiting for the slow sunrise to dry the dew a bit before setting out for the day. Soon enough, though, we were ready to be moving. Our island campsite was comfortable, especially considering the price—a picnic table, fire ring, and open-air toilet hidden back in the woods—but we hadn’t come this far to stay ashore all day. We pulled out our maps and started to look things over.

A southeasterly breeze made the choice of where to begin an easy one: we would sail north, following the original channel of the Flambeau until we reached the northern shore of the flowage, where we would have to work our way westward under a low bridge and around the northern end of the aptly named Big Island. From there, we’d be entering the course of the Turtle River, which we’d follow down the west side of Big Island to the dam. Then north again, roughly paralleling the old Flambeau channel once more past dozens of smaller islands, to close the loop at camp. Ten miles, give or take. Just about right for a casual day’s journey.

The bridge connects Big Island, on the left, to the mainland. The band of darkened rocks along the shore show that it’s more important to pay attention to the “Low Bridge” sign before the summer draw-down at the dam.

With a base camp to return to, we didn’t need to load much gear—just water bottles, rain jackets, and a few snacks. Then we hoisted our sails and shoved off from the beach, riding north on an easy broad reach. After a mile we turned west, skirting a chain of piney islands on a run dead-downwind, jibing now and then. The breeze was light enough to let my Alaska edge slowly ahead of the Phoenix III—no surprise with an extra 10 square feet of sail, and a waterline more than 2’ longer. But it was really no more than a slight edge. The two boats seemed well-suited for cruising together. Before long, I pulled into a shallow reed bed to drop my sail and mast so we could pass under the bridge connecting Big Island to the mainland. I started to pull out the oars, but we were already moving straight toward the bridge. The wind would push us through, I realized. We drifted easily along the marshy shore and under the low bridge, where a bright yellow sign needlessly proclaimed Caution Low Bridge Narrow Channel. I smiled. There was barely room for the hull to slip between the rocky banks—and that in a narrow sail-and-oar cruiser with a 4′ 8″ beam. I could have stood in the center of the channel, knee-deep in dark water, and touched the stones on each shore. But our boats floated through without so much as brushing the bottom. With water levels so low, I didn’t even have to duck my head.

We beached the boats just north of Big Island, at the end of the road on the northern approach to the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage. Big Island is a state wildlife refuge with miles of trails, and a few boat-in campsites on its eastern shore.

We beached our boats on a wide sandy beach on the far side of the bridge, 3′ below the summer high-water mark. A low tide in the north woods begins in July when the spillways open to maintain water flows for the electric plants downstream, and lasts until spring. No need for complicated anchoring systems or clothesline moorings here—at least, not if we returned before April. But I took my 6-lb Northill anchor up the beach anyway, and set it firmly at the sand’s edge, wary of an unintended marooning should my boat somehow float away. Overkill, I knew, but I’ve learned to accept that overkill is generally more tolerable than underkill.

Overhead, gray clouds were breaking up and streaks of bright blue were showing through. We left our boats on the beach and crossed the bridge onto Big Island to walk a long way along the trails. Autumn was just beginning to show itself in muted browns and oranges, and monarch butterflies flickered back and forth above our heads as we dawdled along. That’s the beauty of a small wilderness: no urgency, no reason to push on for mile after mile. Plenty of time for side trips.

Eventually we returned to the boats and set off again. The Flambeau was behind us; our course followed the Turtle River channel west and south from here, down the western side of Big Island. We sailed a slow beam reach through 100 yards of reedy shallows, rudders kicked up but still dragging, before reaching deep water and turning south.

I’ve logged over 1,000 miles in my brother’s Phoenix III, and now, three years after launching my Alaska, I’m nearing that milestone in it as well. The Phoenix III seems to have the advantage to windward, while the Alaska really takes off with the wind behind the beam.

It had been a while since I’d been on a two-boat trip with Lance, and I was quickly remembering how much I liked it. As always, we made for an unruly armada, breaking formation on the merest whim, but generally remaining in sight. With the wind behind us, the Alaska edged ahead at first; then I cut inside a couple of small islands to hug the shores of Big Island while my brother took the outside route to regain the lead. And promptly surrendered the lead again by landing at one of the campsites on Big Island while I kept drifting slowly along the main channel, sitting to leeward to keep my sail filled in the light breeze. And so it went.

As we reached the far western side of Big Island, the winds picked up and the channel veered south, making for a tough beat. With all the miles I’ve spent aboard my brother’s Phoenix III, I’ve come to appreciate its excellent performance to windward. Now, falling behind in my Alaska, I found myself wishing his boat wouldn’t point quite so high, or tack so quickly, or slice so cleanly through the chop. Or maybe it was more the skipper than the boat. Either way, aboard my Alaska it was getting windy enough to be interesting. Before long, I headed into the wind and dropped the sail to tie in a reef. But the wind kept building, stronger and gustier. Even with a reef in, it was getting to be a handful. And then a double handful. I’ve learned that my Alaska, with its narrow beam, slack bilges, and low sweeping sheer, is not shy about dipping a leeward rail when pressed hard. That had been alarming at first, until I learned to trust that it would heel only so far and then keep sailing right along. Still, I’m too lazy to really enjoy hiking out and pushing hard. Better to keep things in control.

We found several long sandy beaches on the western side of Big Island, overlooking the old channel of the Turtle River. With the wind picking up, I took the opportunity to pull ashore and tie in a second reef.

When I spotted a long sandy beach on the western shore of Big Island, I steered right toward it at speed, sheeting in hard, then pulled up the rudder and let the sheet fly just as the stem scraped the sand. With my weight far back on the sternsheets, the boat glided well up onto shore and ground to a stop. I dropped the sail and tied in a double reef. Lance joined me on the beach a few moments later, and tied in a reef as well—more to let me keep up, I suspected, than because he needed it. But I wasn’t going to try to talk him out of it.

Of course, there is nothing so fickle as the wind. The approaching frontal system swept past quickly in a riotous jumble of clouds and rainy gusts, and before I had managed to sail a half mile, it was time for the full mainsail again. Already the Phoenix III had opened up a wide gap. It was definitely faster to windward, where the Alaska lost ground on each tack, its long flat keel needing to be sailed around in a gentle turn. At least I was finally gaining ground under full sail, I consoled myself. Or at least, not losing ground anymore.

Sailing through the narrow dog-leg channel separating our campsite from the next island to the north made for an interesting light-air challenge. With patience, we both managed to reach camp without resorting to oars.

I followed Lance toward the foot of Big Island, dodging through a field of stumps that would have been hidden at higher water. More than once I found myself tacking within inches of a stump I’d seen too late, hoping I wasn’t about to sail right over another that I hadn’t seen at all. Worse still were the occasional angled logs still rooted in the lake bed but barely visible—or not—above the surface. At one point I felt a booming thump on the hull as I sailed right over one of them. All right, at more than one point. Apparently the warning on the Department of Natural Resources’ map I’d picked up at the boat ramp before launching—“The Turtle-Flambeau Flowage has an abundance of stumps, logs, floating driftwood, and rock bars”—wasn’t as irrelevant to a boat with a mere 7” draft as I had assumed, at least not in September. I glanced at the map again. There, too, was the obligatory “The map should not be used for navigation” disclaimer. Busted again, navigating when I wasn’t supposed to. Sometimes it seems like I’ll never learn.

But finally we sailed free of the stump field—which, I reminded myself, has probably done a lot to keep the jet skis away, so it’s not all bad. And then we tacked past the Turtle Dam with its long line of yellow buoys and turned north again, heading downwind along another string of islands. Off the wind, the Alaska pulled ahead of the Phoenix III, sail area and waterline triumphant again. We finished the day by approaching camp from the east, slipping through the narrow dogleg channel that separated our island from its nearest neighbor, skirting a few downed trees that rose from the water like grasping hands, before sliding up onto our home beach again. An evening of thunderstorms and hard rain drove us to our tents early.

The next day brought clear weather at last. The wind had swung around to the southwest, bringing some fierce gusts, but it wasn’t enough to keep us ashore. We launched our boats and tacked down to the southern tip of our island, where we started to beat our way southward through the biggest stretch of open water on the flowage. Again I waffled back and forth: one reef, two reefs, no reefs. Gusts. No gusts. Strong wind. Light wind. Light wind, strong gusts—an interesting combination, impossible to reef for. Lance pulled ahead steadily in the Phoenix III. I tried not to notice.

We worked our way toward the southern reaches of the flowage, taking time to stop at several islands along the way. A few more thumpings of the centerboard when I cut too close to shore at one point reminded me too late of the “abundance of rock bars” the map had warned about. Still, no harm done. At least, not this time.

Navigating the narrow, twisting channels of the far southern reaches of the flowage involved maneuvering in shifty breezes that seemed to come from all directions at once.

Before long we were well past the farthest point that we reached on our last trip two years earlier, into a chain of smaller lakes that was almost a river again. Tacking and jibing in the shifting gusts that swept the narrow channel, we sailed south and farther south. Finally, though, the low water levels defeated us. At the mouth of Otter Creek, at the very end of the flowage, the Alaska ground to a halt among the reeds, keel dragging in the mud. Even in a kayak I couldn’t have made it into the creek and continued upstream.

Forced to turn around, we sailed our way back to open water with no regrets. It had been a perfect day exploring a wilderness that seemed as if it must have been created for sail and oar. No motors, no people, nothing but sun and wind and solitude, the gentle motion of the waves, an occasional splashing of spray over the coaming. Island after island, tall pines and birches shuffling in the breeze, the quiet splashing of small waves on the shore. Seen from a small boat, the southern half of the Turtle-Flambeau seemed like pure pre-industrial north woods—no cabins, no cottages, no roads, only an unbroken forest of mixed hardwoods and pines.

But of course, like so much that seems too good to be true, the Turtle-Flambeau is as much illusion as it is reality. What looked like pure wilderness was only a clever ruse, I knew, the result of what the Department of Natural Resources calls “a 300′ aesthetic zone”—a fringe of timber left perpetually unharvested around the entire shoreline of the flowage, with provisions for selective logging and intermittent clear-cutting still in place farther inland. Still, it was better than nothing at all. Give me a small boat, a sail, and a good pair of oars, and I’ll work my way along the margins of the world past whatever fringes of the wild remain, wherever they lead. That was exactly what I had come looking for, after all.

September days are short in northern Wisconsin, but the evening light can be magical. For our four-day trip, we had the flowage almost entirely to ourselves.

It was late afternoon by the time we headed north toward camp, paralleling a chain of islands up the western shore of the flowage. Light winds gave way to lighter winds. The sun dropped below the trees, but still the light caught our sails in a soft golden glow even as the water beneath grew ever darker. Eventually we turned up a narrow passage that ran through a jumble of small islands, where the breeze faded almost to nothing. We floated up the channel side by side, the Alaska slowly pulling ahead thanks to its larger mainsail.

Still a mile from camp, we starting to lose the wind. Aboard the Alaska, my simple line-and-bungee “autopilot” took over the steering while I got photographic proof that the Phoenix III isn’t always in the lead.

The sky faded to a deep blue, and stars began appearing overhead. And for more than a mile, for more than an hour, we sat silent and unmoving in our boats, drifting along so slowly that it was hard to perceive any motion at all. Only the faint ripple of our wakes and the whisper of moving water along the hull disturbed the sensation of utter stillness. Weight to leeward to keep some wind in the sails. Steering with the barest nudges of the tiller. Slowly and ever more slowly, our two boats slid over the dark water.

Somewhere a loon called. The moon rose slowly over the trees, casting its rippled light over the water. And far behind me, the victim of a shorter waterline and a smaller sail, my brother’s boat hung altogether motionless atop a sea of blackness, white hull clearly outlined against a seemingly endless backdrop of jagged islands and dark pines. An illusion, I thought to myself again. But one worth seeing.

Our trip ended just as the weather turned, bringing a few miles of rowing through dead calms and a cold rain.

Tom Pamperin is a freelance writer who lives in northwestern Wisconsin. He spends his summers cruising small boats throughout Wisconsin, the North Channel, and along the Texas coast. He is a frequent contributor to Small Boats Monthly and WoodenBoat.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Tom, thank you for another wonderful sail-and-oar exploration.

Chris

Very nice article. Looking forward to rowing and camping on the Turtle-Flambeau in the Gunning Dory that Roger Crawford will be building for me this winter. My father’s people have been in central Wisconsin since the Civil War.

I fished that flowage decades ago. Time to go back with a small boat!

I’m pretty sure I store my boat for the winter in the same shed as your brother stores his. How many “Leenhouts” can there be in Wisconsin, after all? (Don’t know if you remember meeting me, but I interviewed you in Port Townsend while writing an article about John Welsford back in 2011).

By all means, take a boat back there someday. It’s a great place to explore.

That Bolger Oyster Skiff was in Pete’s garage when I first stayed there. It took Pete and I a couple more visits to get it finished off; looked really handsome when we’d done. It was a real pleasure to work on it with him.

Isn’t it odd how connected we are in such very unexpected ways.

John Welsford

Tom,

Thanks for this glimpse at a sail-and-oar destination that is not one of the usual suspects.

Great trip!

Thanks for the comments, everyone. If you’re ever around northern Wisconsin with a boat, the Turtle-Flambeau is definitely worth a trip.

Thanks, Tom. You are an artist with words, camera, and a small boat.

Thanks for the kind words—much appreciated. Just don’t forget I have the help of a good editor at SBM!

Looks like a great trip. I’ve spent many years there but never sailed.

Can you describe the two sail boats (name of plan?) in case I wanted to build one of them?

You can read a bit about Tom’s boat, a Don Kurylko-designed Alaska, here, in an entry on Tom’s web site.

The Phoenix III is designed by Ross Lillistone and plans and information about the design are available from Ross and Duckworks.

Christopher Cunningham, editor, Small Boats

Chris already replied with design information on the two boats–thanks for that. The Alaska designer doesn’t have a website right now, but is still selling plans. You can contact him at [email protected]

Alaska is longer by 3′, but really both boats are very similar in the amount of usable interior space they provide. Either could cruise two adults in decent comfort, but more would feel crowded. I prefer them each as a solo boat. I think they are both more than capable, and suitable for motivated first-time builders willing to learn as they go. Good plans and help from either designer.

FYI, those who may be interested in plans for Don Kurylko’s Alaska design will be interested to learn that Duckworks is now selling them, in either paper form or downloadable pdf. You can find them here, along with the designer’s own commentary about his intentions and thought processes, as well as the plans for his larger Myst design.

Tom, your writing always inspires me. Thank you. This article confirms, in my mind at least, that I am not alone in my appreciation of gentle solitude. Your story has come to me after a recent re-reading of L. Francis Herreshoff’s essay, “The Dry Breakers.” I owe you both a debt of gratitude.

Ross, thanks for the kind words—much appreciated. And of course, without designers like you and Don Kurylko (among many many others) to draw boats that inspire and make possible this kind of travel, we sailors would have to go back to backpacking. I much prefer letting a good boat do the carrying these days!

Great reminder of good sailing waters in Wisconsin. I’ll need to head north this summer.

A great story, well told. Thank you. I had great fun exploring those waters on Google Earth as I savored the trip in my armchair.

Google Earth is a great tool for armchair voyaging, to be sure! Thanks for the kind words; I’m glad you enjoyed the article. Getting close to time for another trip in the north woods for me now that May is here.

I am inspired by your article and my daughter and I are planning to ditch our fall backpack trip for sail camping in the Flambeau. Love this: “… moving so slowly that each boat seemed to be floating atop an impressionistic portrait of itself, Monet trading his lilies for lugsails.”

I am just hearing about SBM and hope to uncover more of your writing.

As I am discovering dinghy camping, it seems that the Brits, French, and Australians are more organized and enthusiastic. I hope to find more about dinghy cruising and camping in the Great Lakes region.