The Port Townsend Skiff is a boat with a mission: Deliver stellar fuel economy in a good-looking, well-performing package. Russell Brown, the energy behind this boat, observes that our society has “gone to a totally absurd place” in powerboat design. “We came from having incredibly good-looking, sea-kindly motoryachts,” he says, and we’ve drifted into a place of having overweight, overpowered behemoths. The Port Townsend Skiff, in part, is a “relearning of what’s already been learned.”

The design was conceived in answer to a challenge sponsored by this magazine’s mother publication, WoodenBoat, and its sister, Professional BoatBuilder. In that challenge, we sought a boat of trailerable size and weight that would burn no more than two gallons of fuel per hour while maintaining a 10-knot cruising speed and carrying a family of four—or about 800 lbs. With the design parameters in mind, Russell Brown engaged the talented Seattle, Washington–based design firm of Bieker Boats to develop a boat that could be sold in kit form for amateur construction. And thus the Port Townsend Skiff—and the company that sells it, Port Townsend Watercraft—was born.

Matthew P. Murphy

Matthew P. MurphyThe fuel-efficient PT Skiff handles well under a range of conditions and speeds, can carry a load, and moves well with just a 20-hp outboard.

In describing the concept for the new design, Brown recalls an encounter he had with a native Guatemalan dugout canoe many years ago. That boat was 40′ long, piled high with gravel, and moving effortlessly while powered by a 6-hp outboard motor. The boat’s efficiency was a product of its narrow beam. To move such a load in the U.S., says Brown, “you’d add horsepower—the exact opposite of a canoe.”

The Port Townsend Skiff has a narrow waterline, and to this she owes her efficiency and good ride. The boat is initially tender, meaning that she rolls easily to one side when a passenger steps aboard. “What you get for that tenderness,” says Brown, “is efficiency and ability to travel in rough water.” A water-ballast tank in the boat’s bilge firms things up a bit when the boat is at rest, and it provides momentum through a chop when the boat is lightly loaded. It holds 32 gallons of water, and is self-bailing when the boat is moving: simply open a valve, and the tank runs dry. This boat is designed to move—a commuter, at heart.

Matthew P. Murphy

Matthew P. MurphyRussell Brown (at helm) conceived the parameters for the PT Skiff design, and engaged the Seattle-based design firm Bieker Boats to develop the plans and kit. The windshield’s height is adjustable by means of a light line and jam cleat.

While the PT Skiff’s top-end speed is about 25 knots, speed was not the objective. “You could get better top-end speed in a purely planing boat,” Brown says. But for that, you would sacrifice efficiency and handling in the low and mid-speed ranges, and you’d give up some comfort. The Port Townsend Skiff is one comfortable boat in a chop. “The skinny hull is a pain getting in and out of,” says Brown, “but drive over a lumpy sea, and it really pays off.”

Brown and his wife, Ashlyn, trucked the prototype PT Skiff across country last summer to display it at The WoodenBoat Show. After that, they visited WoodenBoat’s Brooklin, Maine, headquarters, where we were able to test the boat—and compare and contrast it with the Design Challenge winner, Marissa (see page 64). It is, indeed, initially tender, but not alarmingly so. It steers nimbly at low speed and in tight quarters and accelerates smoothly, without the planing bump or ill low-speed manners of a pure planing boat. At cruising speed, it takes a 2′ chop with aplomb, and in tight turns it develops a notable bank. The Port Townsend Skiff’s rated horsepower is 25, and that power will yield the aforementioned 25 knots. The boat we tested was equipped with a 20-hp motor—Brown’s preference— and it topped out at 21 1⁄2 knots.

Matthew P. Murphy

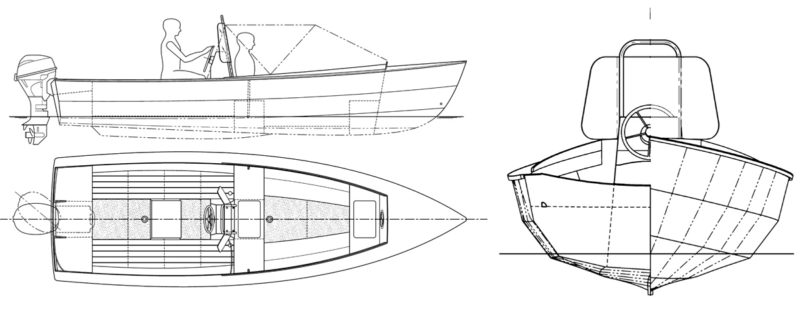

Matthew P. MurphyA sophisticated hull form and light weight are the keys to the PT Skiff’s success. Light weight is achieved through careful choice of materials and good engineering.

It’s not the simplest boat to build,” says Russell Brown of the Port Townsend Skiff’s construction. There is, however, a detailed building

manual that walks through each step of the process. The boat is available in only kit form, and that kit includes hull panels that are joined to full-length sheets by means of a CNC-cut puzzle joint—which is just what it sounds like, and allows for flawless alignment. These panels and other parts are pre-finished before installation.

The hull begins to take shape with the wiring- together of the bottom panels, and to these are joined the next planks. This yields the basic shape of the bottom, which is nestled into a plywood cradle—a part of the kit. There are 10 frames and the transom, and these reinforce the wired-together bottom. The frames have tabs on their edges, and these are indexed to corresponding slots in the skin panels—again making for flawless alignment. Wires are placed at each of these notches to hold things together until gluing. The bottom receives longitudinal members that form an egg-crate structure in concert with the transverse frames, to take the considerable pounding expected on the flatter aft part of the boat. Topside panels are wired to the bottom planks, and this seam is later reinforced by short, tapered frames. In an effort to keep things lightweight, the structure is beefed up where required, and lightened where possible: The bottom panels are 9mm; topsides are 6mm. With everything wired together, the resulting seams are carefully ’glassed.

PT Watercraft

PT WatercraftPT Watercraft estimates that a PT Skiff can be completed, with motor, for $10,000 to $12,000.

I’ve tried here to condense a detailed process into two paragraphs, to give you a sense of how this boat goes together. I’ll end this condensation by simply say- ing that, excluding appendices, the building manual is 258 pages long and includes 630 images. Any attempt by me to explain the nuances of the Port Townsend Skiff’s construction will simply not equal this effort. What you should know, however, is this: The Port Townsend Skiff uses a basic boatbuilding technique—stitch-and-glue— but it uses it in a very refined manner. Careful alignment and gluing will yield a boat vastly more refined than an average stitch-and-glue boat. Craftsmanship is paramount in the construction of a good PT Skiff, but a clever amateur builder should not be daunted by this, because your guide through the process, Russell Brown, is a master of wood-composite construction.

In fact, Russell Brown has been called the epoxy cop. “He’s a clinician with epoxy,” says one friend of Brown’s reputation for clean and precise work with glue. “There’s a lot of epoxy technology in the Port Townsend Skiff,” says Brown—for example, techniques for secondary bonding, whereby bulkheads and other assemblies are fitted and glued to pre-finished hull sides. “There’s a lot more to it than meets the amateur eye. There’s gluing, ’glassing, filleting, and coating, and each requires careful attention if you’re going to get the most out of it.” Brown’s attention to detail is exemplified in the contents of his kit: There are eight different sizes of machined fillet sticks included in the box. “Working cleanly with epoxy makes a high difference in weight,” Brown says. But the results are worthwhile: Brown believes that the boat cannot be built lighter out of another material while still maintaining the same longevity, ease of construction, and low cost.

Matthew P. Murphy

Matthew P. MurphyThe PT Skiff takes some if its design inspiration from the world of performance sailing craft.

So here we have a refined boat and a detailed guide. Although he’d gone to great lengths to make this boat accessible to the dedicated amateur, Russell Brown was initially a bit apprehensive that the details would overwhelm an amateur—that the construction would take an unreasonable amount of time. Testimonial to the contrary arrived at the time of this writing, in early August 2010. Port Townsend Watercraft e-mailed an announcement saying they’d had a rendezvous with their first kit builder and his finished boat. That builder, Jan Brandt, had previously built smaller boats and kayaks. He spent five part-time months, balancing a full-time job and family obligations, building his Port Townsend Skiff.

Matthew P. Murphy

Matthew P. MurphyThe boat’s construction employs proven kit-boat methods, such as the puzzle joint, seen here, that joins the console to the bottom framework.

Curious about the builder’s perspective, I clicked through to PT Watercraft’s online forum, where Brandt had posted the following:

“Hey, I enjoyed it, and now I enjoy being on the water. PIKA has exceeded our expectation in her utility as a runabout and camping boat for the Puget Sound area. We have powered her with a new 25hp E-Tec, which proved plenty powerful. On a recent trip to Deception Pass, fully loaded with 3 adults, 1 child, 8 gal of fuel, and food/gear for the day we averaged 1.25–1.5 gal/h running between 15–18 kn. I am still learning when it’s best to use the water ballast since so far we have been running loaded for every outing.

“One thing is certain, she turns heads wherever she is. Paul and Eric drew a beautiful and functional hull, and Russell provided the insights and experience to build her strong and light. Thanks guys. We are having a blast.” ![]()

PT Watercraft offers a range of kit- boat options for the PT Skiff. The base kit is currently (September ’10) priced at $3,950; the full kit costs $5,680.

For more information about the PT Skiff, visit PT Watercraft.

If one would buy the compete kit, and does not have a build area, is there somewhere to build with professional assistance for an amateur?

Looks like kit is not being made at this time and is unavailable.