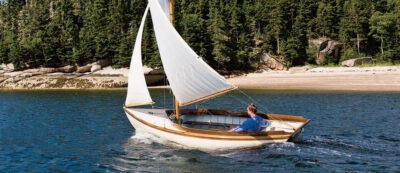

Richard Wilson is a boatbuilding instructor. His smart-looking wooden power dory, Kingfisher, grew out of his desire for a practical inshore craft suitable for sportfishing, flatfish netting, and scuba diving. As a bonus, it also happened to be a good boatbuilding project for his students, which could be completed within the time frame of his course.

Wilson, a master tradesman with years of experience, became a director of his family’s boatbuilding company, Brin Wilson Boats, in 1974, when his father died. In partnership with his brother, he ran the company until 2000, when they made the decision to sell. Today, Wilson is a marine technology tutor at Auckland’s University of Technology, UNITEC.

Photo by John Eichelsheim

Photo by John EichelsheimKingfisher is an outboard-powered skiff whose lineage can be traced back to New England dories. Her topsides are planked in lapstrake plywood, and she has a double bottom that provides both flotation and self-bailing capability.

Wilson owns a vacation home at Marsden Cove, north of Auckland on the shores of Whangarei Harbour, a large, deeply indented, flooded river valley with plenty of the shallow inlets, tidal rivers, and extensive sand flats typical of New Zealand’s northernmost regions. Finding himself without a larger boat for the first time in many years, Wilson decided to design and build a dory after being bitterly disappointed in a lightweight 14′ aluminum runabout he’d bought to explore Whangarei Harbour and beyond. “I hated it,” he explained. “It was noisy, hard-riding, and unstable. And there was no room in it!”

Wilson’s first love is wooden boats. He became interested in design at a very young age. Over the years, ten yachts and three launches ranging between 36′ and 41′ in length have been built to his designs. So designing and building a boat of his own was an obvious solution. The dory is his first small design.

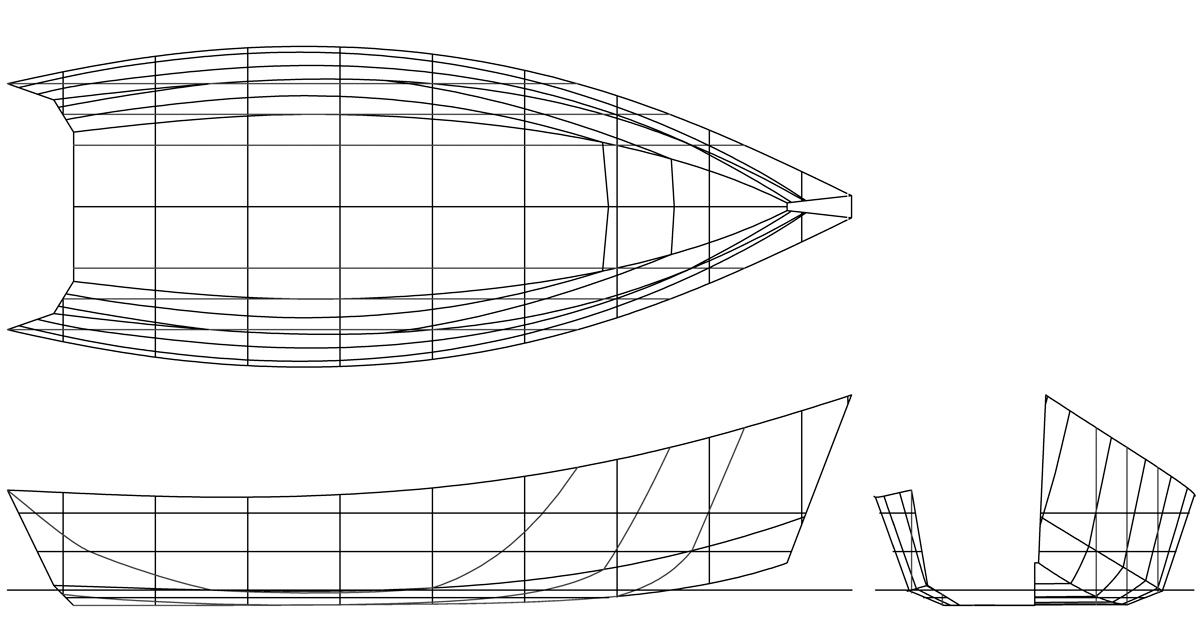

“I wanted a boat with a stable hull that was easily driven by a 20-hp outboard, easily handled by just one person, and easy to build. Kingfisher fits all those criteria.” The boat is a traditional-looking dory with a flat bottom and a double chine. Its high bow, sweeping sheer, moderately raked flat transom, and an outboard motor mounted in a well all contribute to its attractive, clean lines. The decision to mount the motor inboard was partly driven by aesthetics—Wilson feels it’s a better-looking boat in profile if the outboard doesn’t show—and partly by function.

One of Kingfisher’s regular tasks is to set nets for flounder, sole, and other flatfish which abound in Whangarei Harbour, for which her shallow draft is ideal. With this in mind, a raised platform is fitted across the boat’s transom to facilitate setting and retrieving a net over the stern. Working nets over the transom is always the safest procedure, but difficult to achieve with a conventional transom-mounted outboard, which gets in the way and constantly tangles in the net. Aboard Kingfisher, working nets is easy, as is accessing the engine when the boat’s afloat. When the engine’s kicked up it remains inside the line of the transom and well clear of the bottom of the boat.

Photo by John Eichelsheim

Photo by John EichelsheimKingfisher’s outboard motor is mounted in a well—a decision driven largely by aesthetics. It tilts clear of the water while remaining entirely within the boat.

Kingfisher’s construction is in 9mm and 6mm plywood, her topsides lapstrake planked. The bottom is fiberglass-sheathed to just above the upper chine, and all the boat’s timbers are sealed, epoxy glued, and then painted. Wilson uses single-part paint rather than more advanced two-pack systems, as it is more environmentally friendly and requires a less complex application and touchup.

The main floor—the sole—is also fiberglass-sheathed and then painted with a mixture of one-part paint and Epsom salts (magnesium sulfate) to provide an effective nonskid surface. The solid wood in Kingfisher is macrocarpa, a type of cypress, of which there was a supply in Wilson’s workshop at the time of construction. It is commonly used by boatbuilders in New Zealand; North American and European builders will no doubt require a substitute. A subsequent boat was built using yellow cedar, which bends well, is durable, and is a bit more dense than macrocarpa or red cedar.

Kingfisher’s trim is in mahogany, again because it was available to the school at the time of building. Wil- son prefers teak, which can be left to weather, but it’s expensive. The second boat doesn’t use teak either, for the same reasons. (Mahogany does, however, have the advantage from a boatbuilding perspective of requiring several coats of varnish—another skill for Wilson’s students to master.) The students also fabricated the boat’s solid-lumber details, like the knife holders and wooden bow roller, giving them experience in joinery details.

One of Kingfisher’s more interesting features is a sealed floor suspended 4″ above the bottom and 2″ above the upper chine line—effectively an airtight double hull with a volume of 0.5 cubic meter. Aside from offering a flat floor above the waterline inside the boat, which self-drains via two 2″ holes in the transom, it provides buoyancy and security should the outer hull ever be breached. The boat is also easy to clean, as it can simply be hosed down from the inside. Another benefit of the double-chine sealed-floor design is the form’s stability at rest. According to Wilson, a scuba diver can pull himself over the side of the boat with no risk of capsize. Indeed, the boat heels no more than a few inches. Certainly two adults can move around Kingfisher with impunity, barely altering her trim.

The boat is designed to be transported atop a conventional flatbed utility trailer. Most New Zealand households have access to light general-purpose trailers of this type, used to transport bulky or heavy goods, garden waste, and rubbish. The dory sits on the trailer resting on its twin timber keels, spaced 2′ apart and running the full length of boat’s flat bottom. The keels are 43⁄4″ deep and capped with aluminum rubbing strips to protect against wear and tear from contact with the trailer or when taking the ground.

The keels allow the boat to be pulled up a beach or left to sit on the hard when the tide recedes. They also provide lateral stability when the boat’s underway and give a certain amount of protection from damage in shallow water. When the boat’s on plane, air trapped in the tunnel between the keels acts as a cushion, softening the ride.

Photo by John Eichelsheim

Photo by John EichelsheimKingfisher’s twin keels funnel air between them, softening the boat’s ride.The keels also hold the boat upright when beached, and lend great lateral stability when underway.

Kingfisher made easy work of a short, wind against tide chop on Auckland’s Waitemata Harbour, easily soaking up the bumps and delivering a reasonably smooth, dry ride. With two people aboard she achieved a top speed of 14 knots, as recorded on the accompanying photo boat’s GPS. Wilson has managed a maximum of 15 knots with three adults aboard and 12–14 knots with four in ideal sea conditions.

Wilson likes to drive standing up, which is safe enough because the boat is so stable; this steering posture offers better vision forward. When planing, Kingfisher rides on the flat run aft with her bow well up in the air, an impression reinforced by her sheerline. If he’s by himself, the designer employs a simple tiller extension so he can stand or sit farther forward, helping to trim the boat.

In rough conditions, Wilson sits on the timber cross- seat just ahead of the engine box, one of two, painted, solid-wood thwart seats, each pierced with four holes to accommodate fishing rods. Additional angled plastic rod-holders are screwed to the gunwales for a total of 12. This man is serious about sportfishing.

Kingfisher is a remarkably large-volume boat. Unlike some dories, she carries plenty of beam, especially amidships, and her raised floor offers more usable surface area than would be the case if the outer skin were the floor, as is usual.

The interior layout is simple and uncluttered, but very workable: an enclosed locker—essentially an extension of the engine box/well—runs fore-and-aft between the seats down the middle of the boat. A lift-off watertight lid reveals stowage for a portable plastic fuel tank, life jackets, lines, fishing gear, and longer items such as oars and fishing rods. Two inspection hatches in the lock- er’s floor give access to the boat’s airtight under-floor compartment.

Between engine well and storage locker, and part of the same fore-and-aft structure, is an open-topped battery locker. The battery is housed in a proprietary plastic box to protect it from spray or water sloshing around in the lockers, which both drain aft into the engine well. Up under Kingfisher’s short foredeck there’s a self-draining anchor locker below floor level. The solid-wood anchor roller and bollard on the curved foredeck are attractive and functional features.

Kingfisher has been a successful design in every respect: she’s proven to be a capable, safe, stable, and seakindly boat with excellent load-carrying ability. She is economical to run. The design is relatively easy and inexpensive to build, and Wilson’s UNITEC students are able to complete the boat, from lofting to launching, working three days per week over thirteen weeks. Along the way, they learn a useful range of traditional and modern boat-building skills. Best of all, Wilson has created a great little boat that perfectly meets his needs. ![]()

Kingfisher’s combination of flat bottom and double chines provide ample planing surface and minimal pounding. The boat is built of sheet plywood.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2010 and appears here as archival material. The contact information in that Profile is no longer valid and we presume that plans are no longer available.

So many things resonate with this design, among them: simplicity, good looks, and modest power.

Is there anyway to get a set of plans and material list?

I did a search for the designer’s email address and phone number that were listed in the original review and neither was still in service. That’s noted at the end of the review. If any readers know of a source for more information and provide us with details, we’ll pass them along.

—Ed.

Also interested in any plans that might be available.