In 1913, shortly before the start of WWI, England’s Boat Racing Association (BRA), a small club of sailing enthusiasts, called for a design to comply with the following requirements: length 12′, beam 4′8″, and a single 100-sq-ft sail with no battens; she should be a capable rowing boat as well as a good sailing craft, suitable as a tender for larger yachts. The winning design was submitted by an amateur designer named George Cockshott (1875–1952). Eight of the first BRA 12-footers, as they were then known, were built by the Shepherd’s Boat Yard in Bowness on Lake Windermere in northwest England at a cost of £25 each. Several members of the West Kirby Sailing Club near Liverpool ordered BRA 12s and with typical English humor named them after the Royal Navy battleships of the time: DREADNOUGHT, THUNDERER, BELLEROPHON, and SUPERB.

Collection of the Author

Collection of the AuthorThe scene of racing in the 1950s on a lake near the city of Haarlem in the Netherlands is very much the same as it is now.

The design’s popularity spread rapidly. In 1914, eight boats presented themselves at the start of a race in Karachi, then in India. Belgium and Holland adopted the BRA 12s with great enthusiasm. Development of the class in England was curtailed during the war, but in the neutral Netherlands the class flourished and toward the end of WWI there were some 140 of the little boats sailing there.

After the war, voices in England called for an “improved” BRA 12, and the well-known naval architect Morgan Giles came up with a design promised to be faster, more seaworthy, and easier to row. Belgium and the Netherlands by then had the largest fleets of BRA 12s on the water, and they fiercely opposed the adoption of a new design that would make theirs obsolete. The International Yacht Racing Union (IYRU) was called in to arbitrate the situation. While the IYRU approved of the new design, the Low Countries prevailed, and in 1919 at the IYRU meeting the original Cockshott design was officially adopted as a new International class: the International 12-Foot Dinghy.

Roger Smith

Roger SmithWhile the 12′ dinghies are built for racing under sail, they’re outfitted with oarlocks and rowing thwarts to fulfill the class requirement that “each boat shall be built, equipped and finished complete in every respect and so as to be fit for use as a useful yacht’s centerboard dinghy.”

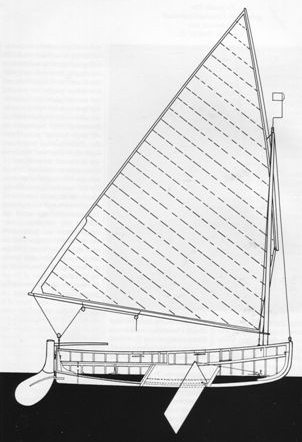

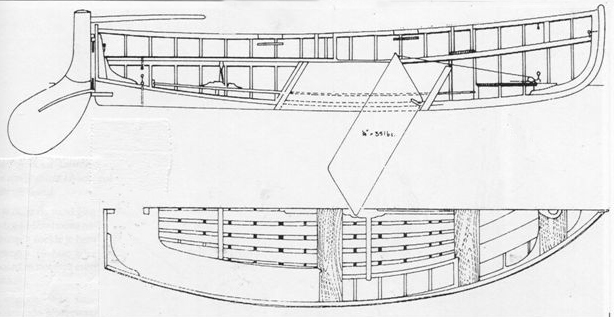

The class is a one-design, meaning that every boat must be identical and have a valid measurement certificate. With their close tolerances, these dinghies were not meant to be built by amateurs, but over the years many have been home-built. Certification required “each boat to be carefully built in strict accordance with the drawings and this specification, and the greatest care must be taken to ensure that all boats are as nearly alike as possible in every respect. Minor deviations from standard may be permitted, at the discretion of the Council of the Association.” The class specifications list the dimensions and material of every part of the boat: the centerboard must be 1/4″ soft steel plate; the steam-bent frames would be of American elm, ½″ thick by 5/8″ wide, spaced 7″ on center; spars were to be solid spruce, although the gaff could be of bamboo; and the 12 strakes are 5/16″ clear straight-grained fir—though later oak and mahogany were allowed as well. Fastenings were screws, bolts, and clench nails and copper, brass, or yellow metal throughout. The hulls might leak when first launched for the season, but after they were fully immersed for a day or so they’d be tight and dry. These dinghies were no lightweights. The 2012 building rules for the Dutch measurement certificate stipulates that the “dry” weight of the bare hull must be a minimum of 229 lbs (104 kg). A new top-of-the-line, race-ready wooden 12-footer built in Europe today can cost as much as €25,000 (about $30,000 US). A good used one can set you back $6,000 to $14,500.

International yards such as Abeking & Rasmussen and de Vries Lentsch built many 12’ dinghies in the 1920s and ’30s, and many of these are still sailing today. The Italian Riva family, famed for their classic speedboats, are also a well-known builders of these boats. Two years ago in England, Stephen Beresford of the Good Wood Boat Company launched a new dinghy with sail number GBR 50.

David Stephenson

David StephensonOn Ullswater, a lake in NW England, Richard Fielden and Stephen Berrisford sail in Force-7 winds on the maiden voyage of dinghy GBR50. She’s one of the few 12-Foot dinghies with reef points.

The dinghy was adopted as the singlehanded boat for the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp. The Dutch took the gold and silver medals—a predictable result, since the only boats entered were the two Dutch ones. The 1924 Paris Olympics saw a French design as the singlehander, but in 1928 at the Amsterdam games the 12 was again chosen as the solo class. Twenty countries competed and this time the Dutch were outclassed: Sweden took the gold, Norway the silver, and Finland the bronze.

The status of the 12-footer as an International class was terminated in 1964, and its popularity declined after that. Despite that, many countries maintained active 12′-dinghy class associations, and upgraded the class rules to suit their sailors’ demands and circumstances. The conservative Dutch changed their rules to improve safety and ease of boat handling: They allowed self-bailers, boom vangs, transom drain holes, and insisted on flotation bags. In Italy, the Associazone Italiana Classe Dinghy 12′ was far more progressive, allowing aluminum masts and booms, pop-up rudders, plywood construction, and, horror of horrors, fiberglass hulls. The Netherlands, Italy and Japan are the current hotbeds for the class, and there are small fleets in Germany, Slovenia, Switzerland, Japan, Lithuania, France, and Turkey. In recent years new boats have been built in Canada, Argentina, the Far East, and the US.

Wietske van Soest

Wietske van SoestAfter jibing in a very strong wind, the bow can dig in but experienced sailors have no trouble maintaining control.

Sailing the 12 does not require great athletic abilities. Anyone can enjoy these boats, whether for relaxation or competition. In light weather the boat is a great singlehander; racing regulations allow a maximum crew of two. The standing lug rig requires the crew to move the yard to the leeward side of the mast with each tack. This is accomplished with tripping lines run port and starboard from the throat. The yard is slightly curved to facilitate this movement, but it still takes a bit of practice. Timing is the key: At the moment that the boat moves through the eye of the wind the yard will slide across with little effort. Sailing in a blow can be hair-raising, particularly on a run with the wind dead astern. With the mast only a few inches aft of the bow, the boat often tries to become a submarine but moving the crew well aft can allow a following wave to flood over the transom. Balance is the key and under ideal conditions one can nearly get the boat on a plane. Jibing in a stiff breeze is practically impossible, and many a racing sailor will tack through a 270-degree turn at a downwind mark. While a reef would be advisable under those conditions not all 12s have them.

Roger Smith

Roger SmithFive dinghies come about in the 100th anniversary race at West Kirby. The woman skippering the Dutch entry #688 is 81-year-old Tonnie Surendonk.

In 2008 an international yearly competition began, aptly named the Cockshott Trophy, and in 2009 the Cockshott family donated a silver challenge cup—first won by George Cockshott in 1902—to be awarded to the overall winner on points each year. Turkey, Italy, and the Netherlands hosted events counting toward points in the years 2010 and 2011 when there were 137 and 178 competitors, respectively; understandably, not all started in all the races. Holland dropped out of hosting the competition, as that country only allowed wooden-hulled boats whereas fiberglass hulls were allowed by the others. In 2012 France, Germany, and Slovenia joined in hosting trophy-point races, with a total of 16 countries represented.

Roger Smith

Roger SmithOn the 100th anniversary of the first race of International 12-Foot Dinghies two Dutch crews race on England’s River Dee near West Kirby in 2013.

In 2013 and 2014 the Royal Loosdrecht Watersport Club hosted the centennial celebrations of the International 12-Foot Dinghy in the Netherlands, with an astonishing total of 187 boats entered, including four brand-new boats. The granddaughter of George Cockshott, Jane Rowe, and her husband Ernest came over from England to take part in the celebrations. Both the Italian and Dutch Post Offices issued special stamps commemorating the centennial. The Associazone Italiana Classe Dinghy 12′ issued a magnificent book: Il Dinghy 12′ Classico Italiano. The Dutch association published their own impressive book, Twaalfvoetsjol: 100 Jaar Klasse (Twelve-Foot Dinghy: 100 Years a Class).

When George Cockshott submitted his drawings to the Boat Racing Association in 1913, it is doubtful he envisioned that a hundred years later the little 12-footer would have a registration in Italy of well over 2,300, that in the Netherlands sail numbers for the wooden 12s have reached nearly 900, and that his granddaughter and 10 countries would be represented at the centennial celebrations of his design.![]()

Evert Moes was born in the Netherlands in 1934 and in his teens campaigned his 12-ft International, H391, PIGLET. After emigrating to Canada in 1960 he became involved in wooden boat building. His latest project was the building of a 9′ 9″ Nutshell Pram from scratch with a modified lug rig similar to the International 12-footer. In summer he sails the waters of the British Columbia’s Gulf Islands.

International 12-Foot Dinghy Particulars

[table]

Length/12′

Beam/4′8″

Depth Amidships/1′8½″

Sail Area/100 sq ft

[/table]

For more information, visit The International Twelve Foot Dinghy Class Association.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Nice boats, great to see racing dinghies that can be rowed. Though standing, not dipping lug, is it not?

Right you are. The International 12-Foot Dinghy Association’s web site steers us toward a designation of standing lug and in John Leather’s book, Spritsails and Lugsails, the 12-Footer’s rig is referred to as a “high peaked standing lug rig.” I’ve made the correction to the text.

Of the standing lug rig, Leather writes: “The standing lugsail…was a refinement of the dipping lugsail…. It was probably developed out of the dipping lug by bringing the tack of the sail to the mast and dipping the heel of the yard around the mast when tacking, instead of having to lower, shift over or dip, and re-set the sail.”

Christopher Cunningham, Editor, Small Boats Monthly

They are generously canvased. Its interesting that few of these boats have reefing points. Maybe they are racing-only craft? I wonder if its possible to to sail one of these single handed in a breeze? The similarly sized Morbic, by Vivier, and Shearwater by Oughtred, both carry a single standing lugsail of 80 sq ft—plus reefing.

Arthur Ransome’s SWALLOW must have been a lot like this.

Ransome’s SWALLOW, described in his series of fictional children’s books titled Swallows and Amazons, was based on a lapstrake dinghy he owned. The boat is described in “The Boats of Swallows and Amazons“ by Stuart Wier.

Christopher Cunningham, Editor, Small Boats Monthly

I am building an International 12 dinghy right now. I have been describing the build in words and pictures on my blog, which can be found at http://www.shipwrightskills.com. Mine will be suitable for more than racing alone and will include reef points.