Not long after our first wedding anniversary—celebrated with an overnight canoe trip on the Narraguagus River in Maine—Sharon and I acquired our first boat, an 18′ Grumman aluminum canoe, complete with transom mount and matching wooden paddles. We are now happily approaching our 40th anniversary and after a lifetime of boating and camping, we felt the urge to semi-retire the old Grumman for a new and special canoe: a long-desired 18′ 6″ wood-and-canvas E.M. White Guide model.

Early wood-and-canvas canoes evolved from Native American birchbark canoes that were in common use in northern New England. Bark canoes were popular, so much so that Maine builders were eventually forced to range farther afield in their search for usable birchbark. The experimental use of readily available, cheaper, and more durable canvas marked the beginnings of a sea change in canoe construction. Early Maine canoe builders developed forms with metal straps where the ribs would be placed. After the ribs were steamed and bent over the form, the planks were applied and then secured with brass tacks. The metal straps on the form clenched the tack points, turning them back into the ribs. The new forms allowed consistent mass-production of canoes at low cost. In the late 1800s, a number of small canoe-building companies formed in and around Old Town, Maine. One of the early successful builders was E.M. White, who modeled his signature canoes after Native Penobscot birchbark designs.

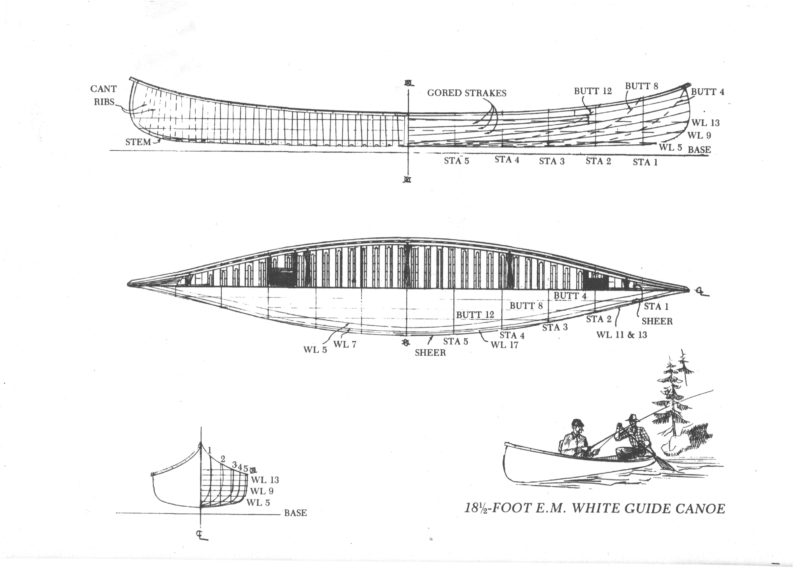

The E.M. White Guide canoe that Sharon and I built is 18′6″ in length overall and has a beam of 37 1⁄4″ and a depth amidships of 13″. Unlike our old Grumman, the symmetrical Guide has a finer entry, making things much easier for the bow paddler. The canoe is slender, with a gorgeous sheerline that distinguishes this canoe from its modern fiberglass or plastic cousins. By omitting intermediate half-ribs but using a keel, floorboards, and lightweight canvas, we brought the overall weight down to just 83 lbs. We wanted to use locally sourced materials as much as possible in our canoe’s construction. The ribs and planking are of northern white cedar. The outwales, handles, and decks are cherry; the inwales are of red spruce, and the seats and thwarts are fashioned of white ash.

Building this “anniversary” canoe ourselves would make it more special. With some past boatbuilding experience, I knew that building a one-off wood-and-canvas canoe could be difficult in part because of the need to first fabricate a rather involved building form. Unless you plan to build a lot of canoes, it is hard to justify the investment of time and money in such a form, which perhaps explains why strip-built canoes are a more popular amateur project.

Fortunately for us, Island Falls Canoe Shop in Atkinson is located less than 15 miles from our home. Island Falls had the forms and jigs we needed to build a White Guide—in fact, Island Falls has many of the original White forms on site, some more than 120 years old. Equally important, Jerry Stelmok and his crew, Keith Stockley and Andrea Myers, have deep experience in building, documenting, and restoring these and other wood-and-canvas craft. We were fortunate to have them as our suppliers and mentors. I began construction, as their student, in November 2014. The project would turn out to be a great way to pass the historically cold and snowy Maine winter of 2014–15.

The definitive book on the construction of the E.M White Guide is Stelmok’s 1980 book, Building the Maine Guide Canoe. I followed this book step-by-step, and began the project in the milling room shaping and sanding ribs, decks, inwales, and stem blanks, creating a “kit” of parts to use in subsequent assemblies. Jerry sawed out the thin (5⁄32″) cedar planking, and together we ran the planking through the thickness sander.

Assembly of the canoe began with bending the ribs—a warming job on a cold winter’s day. The shop was filled with pleasant smells as the ribs steamed. Then ribs were bent on over the form and nailed to inwales previously clamped to the form. When we finished, I had my first peek at what our canoe was going to look like. After fairing the ribs, planking was the next step, and it too was an enjoyable task. Unlike the boatbuilding that I was familiar with, it was a delight to work with such light and easily shaped materials.

Paul LaBrie

Paul LaBrieThe partially built canoe has just been removed from the form. The ends are left unfastened to allow the canoe body to be spread out slightly to ease its removal from the form.

After removing the canoe from the form, it was on to finishing the rest of the hull, including resetting every tack—over 2,000 of them—with hammer and clenching iron. We then installed cant ribs—the small ribs in the extreme bow and stern of the canoe—and the single-piece, breasthook-like decks. We installed temporary thwarts so the canoe would keep its shape during the remaining phases of construction. After getting a few coats of varnish applied to the interior and a coating of oil on the exterior, the canoe moves on to canvasing.

Paul LaBrie

Paul LaBrieThe first base coat of thinned varnish provided good preview of what the finished canoe was going to look like.

A long piece of canvas folded in half lengthwise and stretched between a wall and a post created a tight “hammock” into which we placed the canoe. With specialized pliers we stretched the fabric over the sheer and stems, and tacked it along the edges. After a once-over with a torch to singe the fuzz from the canvas, we applied three hand-rubbed coats of a special filler that waterproofs the canvas and fills its weave to produce a smooth surface. We left the canoe to let the filler dry. That takes at least one month, and in our case this cure time conveniently coincided with the holiday season.

When we returned to the project, the final installation was a straightforward process of fitting finished seats, thwarts, and handles, as well as the construction and fitting of the floorboards. Bringing all of the woodwork to a fine finish required a great deal of sanding and multiple coats of varnish. Over the filled canvas we applied several coats of burgundy-colored paint. We were delighted with the results.

Rosemary Wyman

Rosemary WymanThe final step in canoe construction is adding the shop badge to the deck of the canoe. The folks at Island Falls Canoe say this step is optional, but I thought the badge was a necessary addition. It will always remind me of the project and of the guidance and camaraderie I enjoyed there.

We first launched our new canoe at the Downeast Chapter of the Traditional Small Craft Association spring 2015 gathering on the New Meadows River in Bath, Maine. Spring is a wonderful time to show off a winter’s project to good friends and it helps having knowledgeable folk around to assist with the maiden voyage of any new craft.

First getting into the newly launched canoe, I noticed it was really quite stable—not as stable as our flat-bottomed Grumman, but not tippy either. The gentle roll was to be expected of the semi-oval bottom shape of the White Guide, but I credited the otherwise good nature of the canoe to its length. A shorter canoe would not have been as stable.

Rosemary Wyman

Rosemary WymanThe White Guide is a great solo paddling canoe. White Guides can be built with or without a keel. Those built without keels are more maneuverable and typically used in quick or white water. Our canoe has a keel as my wife Sharon and I tend more to flatwater paddling.

Paddling solo from a kneeling position slightly forward of amidships and with my weight cheated to the side I was paddling on, I was able to make headway into the freshening breeze coming from downriver. The keel enabled the canoe to track well. In short order, however, my 62-year-old knees and legs—not helped by a winter of inactivity—rebelled against my kneeling position. This was not the canoe’s fault. After I took a brief tow from Dave and Rosemary Wyman in their Doug Hylan-designed Beach Pea, experienced paddler Betsy Miller Minott offered her help. With a mid-cove transfer from boat to canoe, Betsy was aboard to paddle the bow position, allowing me to move to the stern seat and paddle from that comfortable perch.

Rosemary Wyman

Rosemary WymanThe White Guide is at its best with two paddlers. I’m paddling with fellow Downeast TSCA member Betsy Miller Minott

With two paddlers aboard, the White Guide flew with easy effort on our part, and we soon passed all of the boats in our Saturday fleet. Windage wasn’t an issue, and the White Guide showed good potential. We quickly reached our island destination, beached the canoe, and settled down for a group lunch.

The tide went out quite a ways during lunch, and our boats were left high and dry. The canoe, thanks to its light weight, was easy for us to carry to the water’s edge. Later in the day, we had an opportunity to save ourselves a lot of paddling by portaging the canoe over a patch of interisland clam flats. Lightness pays dividends at times.

When I arrived back home, I gave the canoe a quick rinse with fresh water and put it safely back in the garage. It’s often been said that simple boats are used more often than larger, more complex ones. For Sharon and me, our experience is that versatile canoes get the most use of all.![]()

After a career in academic technology management, Paul LaBrie operated LaBrie Small Craft, a small boat design, build and restoration company, as a hobby business for 9 years. Paul is currently Treasurer of the Small Reach Regatta and is a member of the Traditional Small Craft Association.

Beam: 36″

Depth: 12 1⁄2″

Weight: 80lbs

Island Falls Canoe in Atkinson Maine, builds, repairs, and restores wood-and-canvas canoes. The shop also conducts classes for those interested in building their own canoes. The White Guide is one of many canoes they have molds for.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Great story, thanks for sharing it. Old wood and canvas canoes are pretty rare here on the windy, salty Texas coast and it was nice hearing about one and your experience building it.

Thanks, Rick!

Great article. I’m sorry I sold my E. M. White a special lightweight Model. Being 83 I now have to find homes for several Old Town wooden canoes.