Building a Thames River Skiff

Within the pages of Eric McKee’s Working Boats of Great Britain there are drawings of a 24′ Thames skiff attributed to W.A.B. Hobbs* at Henley-on-Thames in the very early part of the 20th century. Thames river skiffs were an evolution of the wherries used to transport cargoes and passengers up, down and across the Thames for many years before bridges and other forms of transport put them out of business. Although the vast majority of skiffs have been used for leisure purposes, they are worthy of inclusion in McKee’s book as so many of them have earned a living by being hired out.

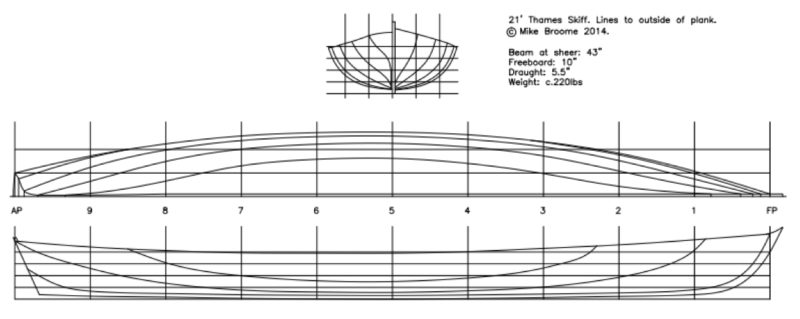

Retired firefighter Lawrence Shillingford decided he wanted to build a version of the Hobbs skiff when he enrolled in the nine-month course at the Boat Building Academy in Lyme Regis, UK, in 2014. The workshop space there was limited so the design was scaled down to 21′ with a CAD program by tutor Mike Broome. The process was by no means simple, primarily because the boat already had very little freeboard. “It was just a question of tweaking it a bit,” Mike said “In essence it’s the same as the Hobbs boat but with more freeboard and a tiny bit more beam.”

Photographs and video by the author

Photographs and video by the authorBuilt in a shop with limited space available, ROSINA MAY is 3′ shorter than the century-old skiff that inspired her builder.

Although Lawrence had planned to retain the Hobbs boat’s two rowing positions, he realized during the lofting that the forward position would be too cramped and that the beam there would be too narrow. He found a drawing of a 21′ skiff with a single rowing position and decided to adopt its interior layout.

Although there is no such thing as a standard Thames river skiff, there are, as Lawrence puts it, “certain ways of doing things.” So, to find out more about skiff-building traditions and practices, he visited two Thames boatbuilding companies: Henwoood and Dean, and Richmond Bridge Boathouses where skiff builder Mark Edwards allowed him to walk around his workshop with a camera and measuring tape.

The building process began by setting up a temporary structure on the workshop floor to which the keel—laminated from two full lengths of oak with a slight amount of rocker—was temporarily fixed. The stem—with the inner part laminated for strength and the outer part solid for aesthetics—and the sternpost were then added. Epoxy was used in all glued joints.

The shapes of the 1″-thick transom and the nine building molds were determined during the lofting process, and the planned position of the top of each plank was also marked on the edges of each of them. Any inaccuracies in the planking lines of a clinker boat will soon be betrayed by the human eye, so after the transom and molds were fixed to the centerline and shored up to the ceiling, a batten was run between each set of planking marks to check the fairness and a few minor adjustments were made.

On each side of the boat there are six ⅜″-thick khaya planks and at the sheer there is a ¾″ thick saxboard, rabbeted so that its inner face is flush with that of the top plank. Lawrence worked from the bottom up, fitting the garboard plank first, a time-consuming process as it was rabbeted into the keel. The academy had obtained khaya, a type of mahogany native to Africa, long enough to do all the planks in one piece, although an entirely forgivable human error resulted in one plank having to be remade with a scarf joint in it. The plank laps were coated with varnish before they were fastened with copper rivets.

Lawrence remained faithful to the traditional Thames skiff system of discontinuous frames. The ⅝″-thick oak futtocks are closely fitted to the inside of the planking and have half joints where necessary. None of the futtocks are taken as far inboard as the centerline. Those in the ends of the boat nearly do and each of them is adjacent to a corresponding floor; amidships, the futtocks and floors are at different stations. Started at the bow, Lawrence riveted the futtocks and floors to the planking and removed the molds as he worked his way aft.

The locks are incorporated into the saxboards and have easily replaced bearing surfaces.

The saxboards were made from especially wide timber so that the fore and aft supports for the oarlocks are an integral part of them. Extended futtocks provide strength across the grain of the saxboards. Each oarlock consists of two vertical tholes and a horizontal sill, all oak and held in place by brass strips so they can be easily removed for repair or replacement.

It was a relatively straightforward process to fit the remaining parts of the boat, including the ½″ x ¾″ khaya rubbing strake; the oak breast hook and stern lodging knees; the stretcher with its three positions to fit rowers of different sizes; the oak and khaya rudder and its yoke; and the khaya thwarts and their oak knees. Time restrictions prevented Lawrence from including two details from the Hobbs drawing: He made slatted bottom boards instead of gratings, and the backrest for the cox’s seat is of oak and khaya rather than framed woven cane.

Another academy student who spent a great deal of time working on Lawrence’s skiff was Brooke Ricketts from Maryland. Brooke’s brother-in-law had felled an oak tree not far from Lyme Regis, and it was from this that the transom, rudder, yoke and seat back were made.

The boat was coated with Deks Olje—three coats of D1 saturating wood oil, applied wet-on-wet, followed by D2 high gloss oil finish—a combination that Lawrence believes will require less maintenance than varnish.

On the academy’s Launch Day in December 2014, Lawrence’s skiff was christened ROSINA MAY, in honor of his mother, and few months later I met with him in Weymouth—about 25 miles east of Lyme Regis—and launched ROSINA MAY from her trailer into the sheltered harbor. Although she felt slightly tippy when I climbed aboard—perhaps not surprising as a narrow waterline beam is an inherent part of the traditional skiff design—as soon as I was seated and rowing it was clear that she is comfortably stable.

It had looked to me as if the distance aft from the rowing thwart to the oarlocks might be too small, but I soon realized that it was just right. Lawrence told me that McKee’s book provided this and other such ergonomic dimensions and that he also had occasional doubts about them during lofting and construction, but centuries of skiff design were clearly proved to be of value.

Each of the students had been obliged to make an oar as part of the course—as well as a hollow plane for working the concave side of its spoon blade—and ROSINA MAY’s oars were made by Lawrence and Brooke. They are to the academy’s standard design but Lawrence and I agreed that oars with blades a couple of inches longer would be better suited to his skiff.

While seating of a sort is provided in the stern, the passenger who’ll be doing the steering sits farther forward to maintain proper trim.

It had been a long time since I had rowed while another person steered. Initially when Lawrence pulled on one of the yoke lines I thought we had been somehow pushed off course by wind or waves and that I should correct it. The reality, however, is that the very long keel gives the boat tremendous directional stability and it needs little help from the oarsman or coxswain to hold its course. Conversely this also makes her hard to turn, so a companion at the rudder is a welcome addition for rowing along a meandering river.

The Thames waterman’s stroke, the traditional form of rowing for a skiff of this type, is described in the Sept/Oct issue of WoodenBoat.

ROSINA MAY is quite heavily built. Lawrence realized she would be when he visited Mark Edwards’s yard but by then he was committed to slightly larger scantlings in some parts of the boat. However, Lawrence is happy that she is strong and, although he isn’t sure of her exact weight, on the launch ramp it was surprisingly easy for the two of us to pull her back up on a trailer with its tires only just touching the water and without using its winch.

Lawrence is contemplating a couple of modifications to the cox’s thwart and back rest to create more leg room. He would, after all, like to have a forward rowing position and so he is thinking of fitting small outriggers—removable for aesthetic and practical reasons—to get the oarlocks far enough outboard.

While Weymouth is geographically the most convenient place for Lawrence to trailer ROSINA MAY from his nearby home, he is looking for a suitable base for her on the River Thames, a wider piece of water where she would be able to mingle with a variety of other elegant rowing boats, and so clearly her natural habitat.![]()

*According to Tony Hobbs, a member of the Hobbs boatbuilding dynasty who was appointed Royal Waterman to Her Majesty the Queen in 1981, he is W.A.B. Hobbs and the book’s reference should have been to W.A. Hobbs, his grandfather. However, the boat shouldn’t have been attributed to W.A. Hobbs. Tony is certain that the boat McKee measured in 1976 was built by Wally Downing in 1906. Downing’s name is inscribed, as is the boatbuilders’ custom, on the underside of the stretcher. At the time, Downing was working for E.T. Ashley of Pangbourne-on-Thames. Ashley’s business and the skiff were later acquired by Hobbs so when McKee measured the boat, she was then owned by Hobbs, hence the confusion, presumably. The boat is now in the Racing and River Boat Museum at Pangbourne.—NS

Nigel Sharp is a lifelong sailor and a freelance marine writer and photographer. He spent 35 years in managerial roles in the boat building and repair industry and has logged thousands of miles in boats big and small, from dinghies to schooners.

Particulars

LOA: 21′

Beam: 43″

Freeboard: 10″

Draft: 5 1⁄2″

Weight: approx 220 lbs

For a lines drawing and a table of offsets, email Mike Broome at the Boat Building Academy. Constructional details largely followed those of the 24′ Hobbs skiff depicted in Working Boats of Britain: Their shape and purpose by Eric McKee.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Those discontinuous frames go back at least as far as the 17th century. The magnificent Queen Mary’s shallop preserved at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich has them as did several other great boats of this type. It must have been common. We used it with building a recreation of George Waymouth’s Light Horseman of 1605. Besides discontinous frames, these boats had the Scandanavian keel and stem structures with narrow deep stems and keels with short vertical scarfs. Waymouth’s boat was a kit boat, something that discontinous frames make easy as the complicated garboard keel lower stem structure can be built and travel as a whole, while the rest of the boat is disassembled for rebuilding.

One of the things that I noticed on these skiff frames is that they are really thin and quite wide so that the vertical nail holes have to be edge drilled with precision. These are all sawn frames and I suspect that the nail holes are drilled off the boat then guide the drilling through the planking. Accuracy is so good and precision is so critical that I wonder if they aren’t done on a drill press.

The other thing I found fascinating in talking with the Thames skiff rowers is “rowing on the strings.” There is a Thames skiff club that shares quarters with the Royal Canoe Club in Teddington. Their boats, at least when racing, have strings that hold the oars down, kind of like gates on modern racing locks. I don’t recall how they are fastened, I think a hole with a knot on one side then a splice that fits over the the other. Anyway, when coming into a float or dock, the string is opened, the oar jumped out then the string reset, and the oar set on top of the string. There is enough pin sticking up so you can still row gently to make the landing or get away from the dock.

A beautiful Thames skiff. Having the video of Lawrence Shillingford rowing made this article really come alive. Thanks.