"We’re actually here!” John exclaimed through his mask as he met Jonathan and me near the water’s edge in Brooklin, Maine. It was late July and deep into the summer of 2020. Every year we cruise our small boats with our informal sailing group of five, usually starting in June and doing one trip a month. This year, things were obviously a bit off axis. Two of our friends were not able to attend. One decided to shelter-in-place at his Southern winter home and the other lived in a state that made him temporarily persona non grata in Maine unless he quarantined. Our long tradition of rafting up in the evenings and creating festive and delicious multi-course dinners wasn’t going to happen either. Hugging and backslapping were right out. However, even with home routines all thrown to pieces, we stood grinning at each other under our masks. We were going to squeeze in at least one short cruise despite the obstacles.

We rigged our sail-and-oar boats. John was in his Ilur, WAXWING, a 14′ 6″-long standing-lug yawl. Jonathan would sail his cat-ketch fiberglass Sea Pearl 21, INDIGO. I was in my second season of sailing MUSSELS OF DESTINY, a 19′ balanced-lug Caledonia Yawl I had purchased the summer before. Wanting to take advantage of the sea breeze, we quickly set out from our meeting spot near Flye Point on the east end of Herrick Bay. A chain of small, ledge-connected islands extends southeast from the point in a rocky finger indicating the way to Pond Island, our destination for the night. The last link of the chain is Green Island, where a squat, pearl-white lighthouse shone warmly in the low light of the afternoon sun. Almost 2 miles beyond Green was Pond Island, its granite shoreline shining beneath an inky-black band of forest. Just visible at the edge of Pond was Lamp Island, a 50-yard-wide nubble of rock with a crew-cut of stubby grass.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

The 2-3/4-mile crossing from Flye Point went by quickly on a single reach through rows of gentle waves. The wind was steady and out of the south at 12 knots, the nippy sea breeze a refreshing break to the unending string of 90-degree days on the mainland. We pulled into the sand-bottomed waters off a 250-yard-long crescent beach on Pond’s north shore. Such beaches are uncommon along the rocky Downeast coast, making this a very attractive anchorage. The sand and shell holding ground is excellent and the bottom is relatively flat if we were to ground out at low tide. Behind the beach, a wide saltwater marsh full of waving grass would have meant being plagued by mosquitoes, but the steady wind kept them at bay. The beach sand had heated up in the summertime sun, and kept us warm in spite of the cool breeze.

We anchored for the night just off the beach in a bay formed by the blunt northwest point of the island and the 1/4-mile-long bar that connects Lamp Island to Pond. I had anchored here many times in the past, so I was almost positive that I would stay afloat throughout the night. The low was going to be around 4 a.m., and, since the bottom is relatively flat, I did not go to the bother of deploying the boat’s beaching legs.

I stepped over the side into waist-deep water, and the three of us waded ashore and walked the slender tide-exposed stone bar between Pond and Lamp, taking care to not slip and twist an ankle on the weed-slick rocks. Lamp is almost 15’ high, a mound of coarse sand and rounded boulders that sit precariously suspended on its sides, waiting to tumble out onto the bar, as dozens already have. To the northeast the rounded 1,500’ mountain summits of Mount Desert Island rose above the horizon, and to the northwest the sun settled into the gentle rolls of the mainland hills.

Night came rapidly as I set up my skinny bunk by laying floorboard sections on two thwarts. With my dark nylon tarp/tent stretched between the masts and my bed made, I slipped under the covers and soon dozed off. I awoke a little later and saw the comet NEOWISE, a bright silver teardrop smudged among the stars. A steady southerly had picked up, and our three boats had swung around with their bows facing the beach.

Later that night, I woke again to an unusual motion of my boat. I lifted the edge of the fly and peered around. My position hadn’t moved in relation to the shore-based points I had made a mental note of earlier, so MUSSELS wasn’t dragging anchor. Everything seemed normal, “Maybe nothing,” I thought and then I felt that odd sensation again, a barely perceptible stop in the boat’s roll. I looked over the rail into the water and the bottom reflected the beam of my headlamp far too brightly. The keel was just scraping the sand. It was 2 a.m., two hours to low tide and I was going to be aground for at least four hours. So much for my confidence of not running out of water! The Caledonia Yawl would fall off the keel onto its garboard at an angle steep enough to roll me off my bunk. I scrambled out of bed to unearth my stowed beaching legs, and in my rush forward I slipped and banged my shins on a thwart. I should have installed them when I anchored or made them easy to retrieve. I climbed over the gunwale into the water and kicked at the shells and sand to make a hole for the landing pads of the beaching legs to keep MUSSELS upright. The boat was quickly beginning to lean heavily into me as I forced the starboard leg into position. “You’re having fun, this is fun!” I tried to remind myself. I got both legs secure and the boat level, but I was soaking wet. I slipped back into my sleeping bag and slept hard until well after sunup.

Jonathan McNally

Jonathan McNallyEarly morning and our three boats were hard aground off the beach on Pond Island and waiting for the incoming tide. Lamp Island sits at the end of the bar that protects the anchorage.

I awoke to the smell of coffee wafting across the anchorage from INDIGO, which was perched on her skinny but flat bottom farther up the beach. I poked my head out from under the fly and Jonathan raised his mug to me. John’s ancient Italian espresso maker began to sputter in WAXWING as he bustled around his boat, a few yards away. The morning was brilliant and clear, the wind robust and steady.

John Hartmann

John HartmannDuring breakfast on Pond Island, I told Jonathan about my midnight misadventure of installing the beaching legs. I hoisted my sleeping bag with the main halyard to air it out before packing up to get under way.

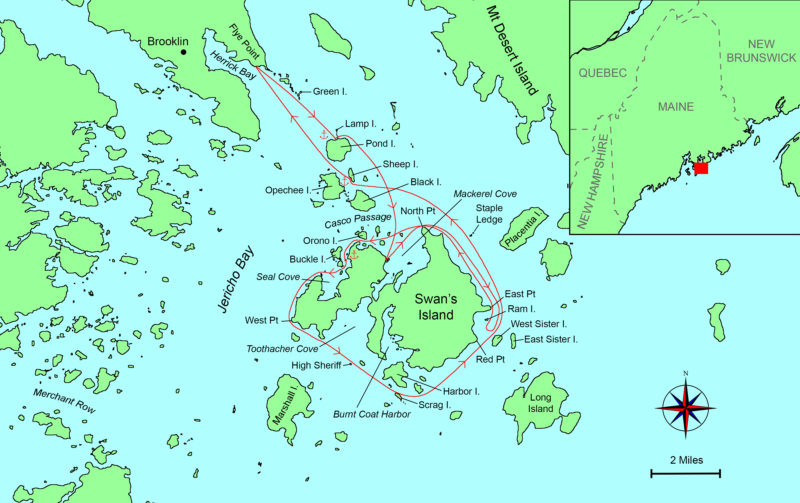

As the water crept over the tide flats and into the anchorage, we sat on the beach and deliberated on how to proceed over the next few days. We could make a long transit toward the mountains of Mount Desert Island and sail around it, or head southwest to the Merchant Row archipelago. I suggested that we sail south to explore Swan’s Island. Swan’s is the largest island in Jericho Bay. It’s quieter and doesn’t attract as many boaters as Mount Desert and Merchant Row, and yet it has an interesting coastline with many intriguing nooks. It would be new territory for us to explore.

We decided to circumnavigate Swan’s clockwise. The south-west wind would allow us to sail on a reach from Pond to Swan’s and down the east side of both islands instead of tacking upwind to the west side and struggling through Casco Passage, which was in flood and notorious for strong currents.

Jonathan McNally

Jonathan McNallyMUSSELS and I plowed southward to Swan’s Island with two reefs in the mainsail and one in the mizzen.

The forecast was calling for 15 knots, and outside of the lee sheltering our anchorage whitecaps were already showing. I tucked two reefs into the mainsail. When the incoming tide had our boats floating again, we all made ready and raised sails and anchors. I released the mizzen, grabbed the main boom, and backwinded the mainsail; MUSSELS’ bow slid easily away from the beach and toward the bar we had walked last night. We sailed downwind over the paper-thin water covering the rocky bar and, once clear of Pond Island, turned south on a close reach for Swan’s Island.

The wind was strong enough to keep MUSSELS’ gunwale pressed to just above the water. The bow sent frequent wide splashes to leeward and foam streamed alongside, trailing behind in a long tail. The uninhabited islands of Sheep and Eagle, just south of Pond Island, passed swiftly. The water turned midnight blue as the land slowly sank behind, leaving nothing ahead but Swan’s. The three of us made the 4-mile crossing in less than an hour and barreled into Mackerel Cove on the island’s north side. We sailed through its 1 ½-mile-wide entrance to the west side of the cove to a tiny protected pocket tucked behind a tiny islet and overlooked by a shuttered vacation home. With our boats anchored in tight formation directly off its front lawn, we reviewed our plan. We would sail downwind out of Mackerel Cove to North Point and then reach southward down the east side of the island. After turning the corner on the southern end, we’d head west to the center of Swan’s and find a place to hole up in Burnt Coat Harbor.

We finished our quick lunch at high slack tide, set sail, and sped downwind out of Mackerel Cove. After rounding North Point, we turned south onto a long reach down the east side of Swan’s, passing rocky outcroppings, long skinny beaches, open meadows, and forests of fir and spruce.

Christophe Matson

Christophe MatsonJonathan in INDIGO enjoyed the fast broad reach down the east side of Swan’s with his sail reefed with a few wraps around the mast.

John had recently installed a hiking strap in WAXWING to keep her flat and fast, and sat on the rail with his upper body stretched out over the water. Jonathan, in INDIGO, sped back and forth between me and John, curling up a bow wave, his rudder halfway kicked up by boat speed. Ahead of us, less than 3 miles away, was Long Island and the town of Frenchboro, known among islanders as “the last stop until Portugal.” It was shrouded in a wall of fog with just a few trees jabbing out of the blanket. We quickly arrived at the dun-colored rocky finger of East Point and turned to sail closehauled toward the pass between West Sister Island and Swan’s. Rust-colored slabs of vertical granite were broken by small pocket beaches of tombstone-gray gravel.

Between the Sisters and Red Point on Swan’s there is a shoal covered by just 15′ of water at low tide. With the sustained southwesterly wind and the tide now on the ebb in the opposite direction we were faced with ever-growing swells. A lobsterboat came up from behind and powered up, gaining speed and momentum. Sooty diesel exhaust roared out of the stack in an angry growl as the boat charged into the building waves, cleaved them in two, and quickly disappeared behind the swells. If that was what it was needed to navigate over the shoal, we were sorely lacking adequate horsepower.

WAXWING completely disappeared behind a rising hill of dark azure water with only the streaming red pennant of his yard visible. As John came bounding up over the next face, MUSSELS climbed over a sweeping roll. Up on high I could see to the center of the shoal, where chaotic tightly packed waves with steep faces looked decidedly unwelcome. The water closer to shore was less turbulent and perhaps navigable, but a jagged collection of boulders and steep rock walls would be immediately on our lee. The heavy fog was now rolling in from the sea and cloaked the outer East Sister Island into obscurity. If anything happened here, and it was quite possible something could, the consequences would be catastrophic. Even though we were all in perfect control of our boats, continuing south was a needless gamble. As we sailed ever closer to the maelstrom I called over to John in WAXWING, “Are you feeling it?! I’m not feeling it!”

“I’m not feeling it either!” John shouted back. I waved vigorously at Jonathan in INDIGO who quickly worked his way to our position.

“Not a lot of margin for error here, chaps!” bellowed Jonathan over the wind as he approached us, momentarily dropping out of sight between windblown crests.

The prospect of an early dinner in the protection of Burnt Coat Harbor was but 3 short, enticing miles away. Turning around meant sailing against the ebb and, at least, backtracking the 6 miles we had covered since lunch. John stood up one more time and looked at the rowdy waters, paused, and then turned WAXWING away to northeast. Jonathan and I followed and we sailed northward again.

An hour later, we came around North Point for the second time that day and started the grinding work of tacking against a strong westerly that wrapped around the top of Swan’s. With the hour now getting late, we decided to pass Mackerel Cove and attempt an ambitious push against tide and wind to Buckle Harbor on the northwest side of the island.

There is a narrow deepwater channel squeezed between Orono Island and Swan’s that lay before us and our goal. Steep rock slabs rise out of the water, and the wind and current get pinched between the islands. Our three boats battled forward for dozens of tacks gaining only marginal westward ground with each pass. If we were to make headway against the flow, there could be no half-hearted, sloppy sailing. Any large delay and we would run out of daylight and wind and would have to fall back to Mackerel Cove. Anchored off to the south side of the channel a lone sailor in a 35’ sloop watched us while sipping a cocktail. INDIGO led the pack with WAXWING and MUSSELS trailing behind. Fortunately, the wind held long enough and we broke free of the current in the channel and turned south into the lee of Buckle Island, and ghosted into the opaque jade water of Buckle Harbor.

John Hartmann

John HartmannFinally at anchor in Buckle Harbor after a long day of sailing, we enjoyed the sunset before going to bed. The anchorage was glassy-calm all night and provided a much-needed night’s sleep.

We sailed to the southern end where deeper-draft boats could not venture and slid onto the muddy flats that extended out from Buckle and the two islets to its south. Devoid of houses, the harbor was peaceful and encircled us in a protective ring of weed-covered granite. Tall fir trees, clustered like spires on a Gothic cathedral, were festooned with wispy moss and the clouds glowed above in the sunset like fire-lit logs.

Christophe Matson

Christophe MatsonJohn’s homemade tent for WAXWING is streamlined to help the mizzen keep the bow to the wind. Weights hanging on the edge keep the fabric taut without having to resort to snaps or hooks.

We sculled off the mud and tried to find water deep enough to float us all night and avoid settling on any of the boulders we saw scattered just below the surface. We each deployed the anchors when we found our spots with enough room to swing. Sitting on MUSSELS’ floorboards I ate a dinner of fresh spinach raviolis with pesto as I watched the last light filter between the slender trees, wishing we were rafted up enjoying this moment in each other’s company. I passed on washing the dishes, deployed my tarp/tent and, in a haze of fatigue, burrowed into my sleeping bag on my floorboard bunk.

Christophe Matson

Christophe MatsonAll was quiet in Buckle Harbor during the morning at low tide. We had all done a careful reconnaissance during the high tide before setting anchor and thus avoided waking in the middle of the night, perched on a boulder by the falling tide.

The morning was clear and utterly calm. The fog stayed south of Swan’s. We gathered on the small beach on Buckle Island and walked to the large flat ledges on the sea side and looked out over a placid Jericho Bay. We decided to continue sailing counterclockwise around the island. The weather forecast was excellent, but with winds expected at 10 knots or less. We could tuck into Burnt Coat Harbor as we’d previously planned or perhaps finish our circumnavigation depending on our speed.

John Hartmann

John HartmannDuring breakfast, Jonathan relaxed under his umbrella while the tide rapidly filled Buckle Harbor.

We’d decide as the day progressed. John was eager to get started, and soon he rowed WAXWING out of the harbor into Seal Cove and made his way south. Jonathan and I groused loudly about how rowing is work, not recreation, and we took our time packing up, hoping that some wind, anything, would show up by the time we were ready to leave.

John Hartmann

John HartmannI scanned southern Jericho Bay looking for the faintest sign of wind and finding none. A lobsterboat worked the traps; the small islands of Merchant Row are on the horizon.

The wind did not materialize, so Jonathan and I reluctantly rowed south across the mouth of Seal Cove and down the rocky west coast of Swan’s. With each hint of a breeze Jonathan quickly raised sail only to have the zephyr vanish, and he bobbed becalmed in the gentle swell. With binoculars, I watched WAXWING round West Point, John’s spoon blades flashing in the sun in a steady rhythm, until he disappeared behind the curve of land.

Jonathan McNally

Jonathan McNally We decided to stretch our legs for a few minutes and tucked our boats into a small pocket beach next to Buckle Harbor.

Mixing in some ghosting and rowing and foolishly committing to neither, Jonathan and I struggled to catch up to John. We headed out across the mile-wide opening of Toothacher Cove, where large schools of fish flashed by on the surface around us in agitated frenzy. Seals, whose heads popped up intermittently, were the apparent cause of the ruckus.

Christophe Matson

Christophe MatsonJonathan rowed INDIGO while drying his clothes and protecting himself from the sunlight with his umbrella. His Sea Pearl has a flat bottom with no skeg, so a few inches of leeboards in the water offer improved tracking when he’s rowing.

We aimed for a 20′-tall knob of broken brown rock called High Sheriff, where John was waiting. Now early afternoon, the wind started to pick up out of the southwest and the tide began to ebb. John was interested in going up Burnt Coat Harbor, but I did not feel like fighting the ebb in the narrow channel with a multitude of fishing boats plowing in and out. We stayed on the outside of Harbor Island which defends the opening of Burnt Coat Cove from the Atlantic, and made our way to the north side of small, steep-sided Scrag Island, which is available for recreational day-use. We dropped our anchors in a small cove just off a steep-pitched cobblestone beach. The water in the cove was perfectly clear and, while looking over the side, I spotted dueling Jonah crabs, a lobster meandering across the bottom, and flounders lying camouflaged in the sand. I took off my shirt and plunged over the gunwale of MUSSELS, and went for a rejuvenating swim in water markedly colder than that at Pond Island.

Hoping the 8-knot breeze would continue until sunset, we planned to shoot for a long 8 1/2-mile leg all the way back to the south side of Pond Island. There is a large anchorage surrounded by Sheep, Black, and Opechee islands, but only deep enough for small boats.

Our pace against the ebb was steady but slow. With a steady southwest wind, we sailed wing-and-wing uneventfully over the shoal between Red Point and West Sister Island. We passed little Ram Island capped with just two knots of trees and then around East Point, completing the circumnavigation of Swan’s.

We headed north. Lobster buoys trailing seaweed leaned away from the ebb’s strong pull as our boats crawled against the push of water. The wind shifted to the northwest, and beating to weather, MUSSELS made more leeway than INDIGO and WAXWING and slowly slipped eastward. Closehauled, she lost even more ground as I had to come off my course by a few points to prevent pinching. Despite my best efforts, the 140′ summit of hulking Placentia Island, a mile off to starboard, remained unmoving under the boom. Disappointed in my progress, I sat idle looking at a seagull standing on a thick mat of seaweed 20’ off starboard. This was somewhat curious, as I had never seen a mat so thick that a seagull would perch on in open water. I stood up and realized it was the summit of Staple Ledge, a needle of dark rock that juts off the bottom of the ocean floor and just happens to kiss the surface at mid-tide. The view had been blocked by my mainsail and, in my ennui, I never bothered to check the chart or my position. I had missed the rock by a boat length.

Over the next two hours of slow closehauled sailing, I covered the remaining 3-1/2 miles to Sheep Island, where I could turn into the harbor we had chosen that night. The more weatherly INDIGO and WAXWING were there waiting for me.

Christophe Matson

Christophe MatsonJohn carefully set WAXWING’s anchor off Opechee Island before another calm evening.

As the sun touched the horizon, our anchors were settled into the mud bottom of the cove. Low-lying Sheep Island, covered in stunted trees and scrub, was off our east. Opechee Island and Black, heavily forested and seemingly impenetrable with no obvious entrances into the tightly packed firs, were to our west and south. We all quietly prepared our dinners and didn’t talk much, immersed in the isolation. On distant ledges beyond Sheep, seals barked and sang, and schools of bunker fish were chased along the surface creating the sound of a large crashing wave, incongruous with the dead flatness of the water.

That night was again clear with no moon and no artificial lights visible. The islands were blank dark silhouettes against the sky. We were the only three boats within miles. Leaning over the side of MUSSELS, I swirled the water with my hand and the bioluminescence blazed through my fingers, bright playful twinkles of light against the black of the water. I stripped down and slid over the side. The water erupted in an otherworldly, electric cyan. I swam to INDIGO and Jonathan watched as I streaked around his boat. “You look like a comet!” he exclaimed. I splashed the water wildly and laughed, which echoed around the tree-lined shores. I turned onto my back and relaxed my body, easily floating in the water. Suspended between sea and sky I gazed at the Milky Way’s foggy jog across the night. To my sides the blinking bioluminescence contrasted with the harder silver stars above. Behind me comet NEOWISE hung bright and cold. I took a long breath, curled underwater, and swam beneath MUSSELS. I passed the glowing curve of the anchor rode as I followed a path of light released by my hands stretched ahead.

John Hartmann

John HartmannBefore crossing back to Brooklin on the last day, we waited for the tide to cover a wide shell bar so we could escape our overnight anchorage.

In the morning we woke to a thick fog, tenacious and clingy, and dampness permeated my sleeping bag. Nothing outside of a drybag was spared from the wet slick. After breaking down our overnight shelters, we planned the return to the mainland. The air was oppressively calm and heavy, and rowing was the only option. Hunched over our charts we plotted a magnetic course and confirmed with each other the headings and time estimates. Cutting through the cotton of fog we could hear the deep diesel rumble of lobsterboats working the traps in Jericho Bay.

Jonathan McNally

Jonathan McNallyThe tide had come in enough to float my boat, but the water wasn’t deep enough yet to row. I sculled MUSSELS over the shell bar to deeper water on the other side so we could begin our passage home.

We hauled radar reflectors up the masts and started to pull for home. Jonathan in INDIGO blazed his own path and soon disappeared into the fog while John and I pulled together side by side, making frequent compass checks and course corrections. The world was reduced to an intimate circle, with just our two boats and isolated lobster buoys appearing for brief moments. There was no visual reference to distance covered, only our wristwatches marked the passage of time. Lobsterboats continued their work from trap to trap, motoring and then idling on a constant regular loop, their distance from us inscrutable. The slow, steady tempo of the oars left a trail of expanding rings which marked the way we had come, trailing endlessly behind the stern and absorbed by mist.

Suddenly a mooring ball passed off to starboard and a looming shadow materialized into a hulking steel fishing trawler as we entered the harbor right on the schedule we had estimated. The dock soon became visible as the fog broke into wisps closer to shore. Jonathan was already climbing out of INDIGO and tying her off. John and I nudged up behind her and secured our boats. We didn’t travel hundreds of miles or break any records, but we had traded daily worries for stars and fog, rowing and sailing. This year, it was an accomplishment.![]()

Christophe Matson lives in New Hampshire. At a very young age he disobeyed his father and rowed the neighbor’s Dyer Dhow across the Connecticut River to the strange new lands on the other side. Ever since he has been hooked on the idea that a small boat offers the most freedom.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Great story Christophe. Makes me quite Maine-sick. Seriously bummed out that COVID cancelled the trip to Brooklin and the Small Reach Regatta this year. Glad you guys still manage to get together on a regular basis. Send more reports!

A

Beautiful cruise.

Hi Christophe,

A great article! Are you willing to elaborate further on the comment you made about the relative sailing performance between the three designs? How did each boat compare in sailing performance over the course of the trip?

“The more weatherly INDIGO and WAXWING were there waiting for me.”

Hi Christophe,

What a wonderful cruise! I salivated as I followed your story and admired the wonderful pictures, all along looking at my Maptech Chart to see exactly where you were. I’ve had my Ilur CLARISA at a SRR only once but it was enough to fully appreciate your observations and descriptions. Thank you for taking us along for the ride, even if only virtually.

Caleb,

This is tantamount to opening a Pandora’s Box of subjective feelings that can quickly become overwhelming.

I will try to keep it simple for the purposes of the comment section.

All of us cruise together often. The boats play very well with each other and each have strengths and weaknesses depending on conditions and point of sail. WAXWING is a standing lug with a sprit boom. The sails were perfectly sewn by Dabbler. John has spent a very considerable time fine-tuning the rig. Her centerboard and rudder are carefully shaped using the Mik Storer foil-shaping method. She is weatherly and expresses little leeway when sailing close-hauled. Jonathan in the Sea Pearl is sailing a production-built boat. I have owned and cruised a Sea Pearl for several years and can attest to their fantastic sailing abilities. I tacked mine through 100 degrees and enjoyed good speed upwind. The Sea Pearl exhibits some leeway, the leeboards are known to be a bit undersized, but the speed made up for the slip to leeward. I am relatively new to the Caledonia Yawl as this is my second full season, but I am not new to balanced lugsails. My Goat Island Skiff, in which I sailed and cruised extensively, could tack between 90-105 degrees depending on sea state and wind. Her deep, foiled daggerboard allowed little appreciable leeway, but her big sides would become a hindrance in big water when sailing upwind. Currently in my Caledonia Yawl, MUSSELS, I am tacking though 110+ degrees, so I am not pointing as high as the Sea Pearl or the Ilur. Her speed is good, but her leeway is also more than I would like. I did not build this boat and the centerboard is currently a slab of wood, which I plan on shaping using the aforementioned Storer method over the winter, in the hope of gaining a few degrees to windward. The CY, however, is a very capable, voluminous, dry, and comfortable boat. She can really fly off the wind and pulls easily away from the pack (but keep in mind she’s 19′ long and WAXWING is not even 15′). I am looking forward to next summer when I can fine-tune her rig some more and become more weatherly! In the meantime I would be happy to be sailing on any three of these boats for this type of cruise, and accept that some days I will be faster and others I will be slower no matter the boat.

Hi Christophe,

Thank you for your excellent response to my question.

Shaping the centerboard will help tremendously. Last summer I lent RANTAN on a camp cruise and the folks using her put the daggerboard in backwards. I could’t figure out why she was doing so poorly up wind, until after the trip.

Classes like the Sunfish limit the amount of shaping you can do to the daggerboard.

This summer, on a trip with John and others down to Marshall, a week or so after this one, when I was sailing RANTAN, I was easily out-sailing the fleet going upwind. Typically other CY’s have sailed with me upwind at the Small Reach Regatta.

On that same trip, we took most of the morning sail-rowing to get through Casco Passage against the tide in light to no wind on the way to Buckle from Pond. I should have dropped my mast and committed to rowing, as rowing in the current with the stick up was not any fun.

Ben, what type of boat is Rantan? I am looking to build another sailboat that performs better than my Caledonia Yawl (sloop rigged) that I built 6 years ago. Although the CY seems to point pretty good, I was hoping the sloop-rigging would give an advantage over the balanced lug/mizzen rigged version. The centerboard is foil shaped per plans from Iain Oughtred, at least as well as I could shape it. Is the Storer foil different?

Thanks

Gilbert,

Ran Tan is the Harrier design by Tony Dias. Not as much volume as the Caledonia being 17′. Can do a bunch of different rigs, but I have a very high-aspect-ratio standing lug set on a carbon mast that is close to 19′, 100 or so sq. ft. with full battens, maybe 7′ or so on the foot and a sleeved carbon yard. Tiny mizzen to balance her. You can find some pics on Tony’s site, I think it is Dias designs. One of the old Small Boat designs has an article. A much easier boat to row than the Caledonia. Narrow flat bottom grounds out flat. About 250 lbs. Hull has been tweaked so I’ve had it planing time to time. And I have it set up for comfortable rail riding ( 4″ or so rail) with a hiking strap.

I forgot there is a write up in the Feb 2020 SBM for the Harrier, built as a stripper: FALCONE de PALÙ

Beautifully written!

The Harrier,FALCONE DE PALU,I built some years ago, is a wonderful boat for sail and oar. We are sailing her in Venice Lagoon, Laguna di Grado and in Golfo di Trieste. Participated in several regattas for “Barche d` Epoca” in Trieste, Italy, Pirano and Izola, Slovenia-Istria.

Using a “Tiemo” – boat tent, we can sleep on the floorboards quite well and cozy.

This summer, we want to participate at the Venice Lagoon Raid, a sail-and-oar event, we participated several times with our 16′ Cosine Wherry MARIE.