There’s an interesting exhibition of art at the Georgetown Historical Society in Georgetown, Maine. Some of the pieces on display are an unusual pairing of abstract painting and wooden boat models. The disciplines of art and boatbuilding have very different goals, one purely aesthetic and the other quite practical, but both require thoughtful attention to form. The artist/boatbuilder who created these pieces is Willits Ansel.

“For boat builders to paint is not unusual,” Willits noted in his comments about the exhibition. “Fairness and balance are factors to be mindful of, whether designing a boat or painting an abstraction. What may make for beauty, particularly, is line, and balance, found in each though more a necessity in the models.”

Evelyn Ansel

Evelyn AnselThe opening photo at the top shows the installation at the Georgetown Historical Society gallery. The piece here is a composition of models and half models, all initially created as boatbuilding aids.

Willits was in the middle of preparing for the exhibition when he passed away unexpectedly in April at the age of 90. His granddaughter Evelyn Ansel, an SBM contributor, wrote: “He was a painter all his life, and his last project was a collection of abstract pieces, to which he attached his entire life’s work worth of half models. Feels a little like the joke was all on us; I can hear his wicked giggle every time I look at them. He died so suddenly that a few things were half finished, but we put the show up anyhow.”

I didn’t know about Willits’s art previously but I knew of his work on historic small craft. His book, The Whaleboat, published by Mystic Seaport in 1978, was one of the first books I bought when I started building boats that same year. His interest in art preceded his work with boats. When he was 12 he took a still-life class, he started painting when he was 17. In 1970, at the age of 41, Willits went to work at Mystic Seaport and began building small boats, about 100 of them over the course of his life.

Evelyn Ansel

Evelyn AnselWillits writes: “Regarding this exhibit, I am of two minds. One is to let the abstractions and models speak for themselves and leave interpretation to the observer. The other is a written explanation where I attempt to give meaning to the abstractions, the builder’s models and why I have now put the two together. The latter is a valid question and not that easily answered. In a sense, they are worlds apart, but in some respects there is commonality.”

It’s not surprising then that his two pursuits, art and boats, intersected. (As for the “joke” of hammering a half model to the frame of a painting with a couple of galvanized box nails, I think it’s a revealing act of irreverence, a hint that the value of creation is in the process, not the product.)

Like Willits, I came to boatbuilding after being drawn to art. In high school, my interest was in science up until my junior year when I was required to take an art class. That quickly and unexpectedly changed my trajectory. Going into college, I knew I would major in art and ultimately set my sights on portraiture. While that discipline produces quite different results than the abstract art that captured Willits, the pursuit of beauty, line, and balance is the same. After I graduated in 1975, I continued drawing portraits in pencil and did a couple of busts in modeling clay.

This self-portrait that I did in my senior year at Bowdoin College was the beginning of the direction I thought I’d take after graduating.

At that time, I also was doing a lot of hiking and bike touring, and liked to travel under my own steam. I decided to build a dory skiff to cruise the Inside Passage. As the planking went on the molds, the curves began to appear and I found them mesmerizing. I experienced what Willits wrote: “What may make for beauty, particularly, is line.” At the end of a day’s work on the boat, I’d sit in a corner of my shop and scan the shape as if staring into a campfire. Building the boat was no longer just a means to an end, but the creation of sculpture.

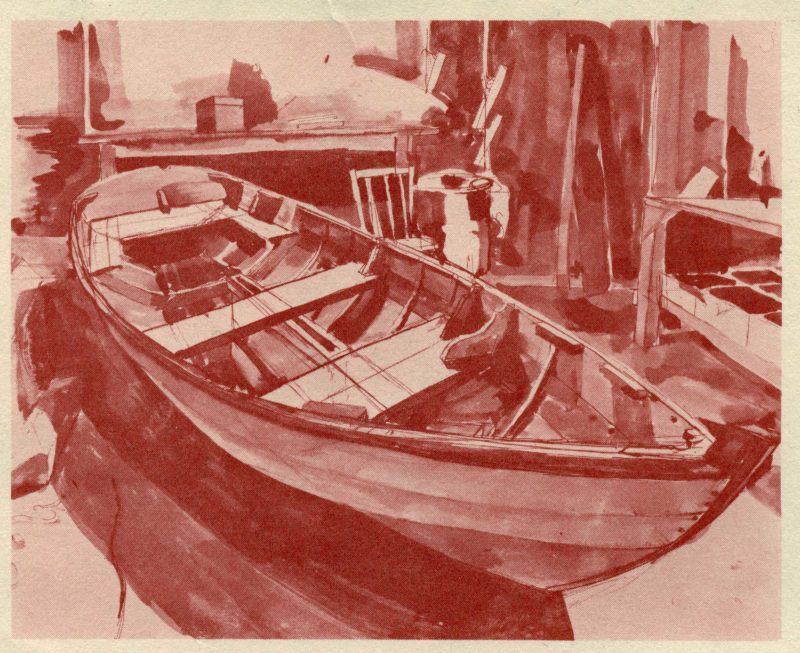

When I built my first wooden boat, I was still focused on art, and did this watercolor of the dory skiff nearing completion. (From a print of the original)

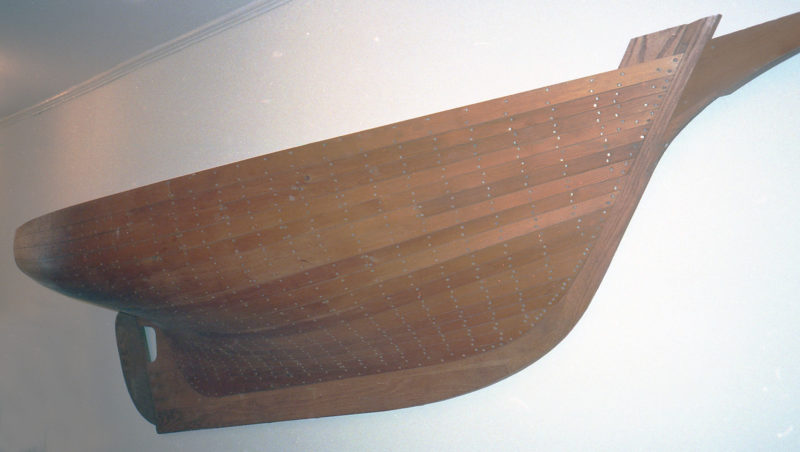

When I taught at WoodenBoat School in the ’90s, there was a planked half model on the wall of the school’s dining hall. It was a carvel-planked keel boat, a form defined by the flow of water. As sculpture, the play of convex and concave curves and the transitions from one into another are like those on a young face, from cheek to the bridge of the nose or from lower lip to the chin.

I was enthralled by this planked half model in WoodenBoat School’s dinning room. In its transitions of convex and concave curves I found echoes of the human from.

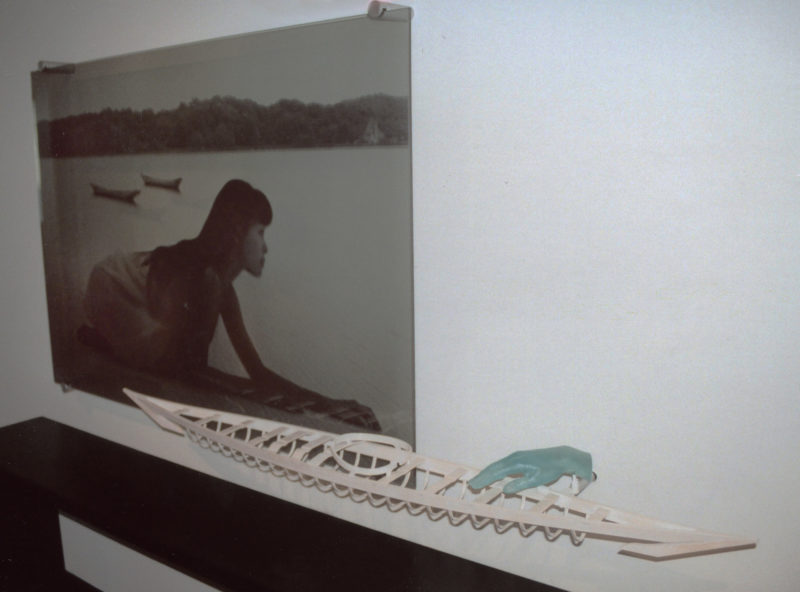

Years later, my intersection of art and boatbuilding reached its apex in working with my friend Mary Van Cline, a Northwest glass artist well known for combining photographs with glass sculptures and panels. We had met as sea kayakers, discovered a mutual interest in art, and ultimately collaborated on some mixed-media pieces. I made frames of traditional kayaks—most of them at scale, one full size—and modified versions of Alaskan Inuit single-bladed paddles; she made hands and faces cast in glass from life molds in addition to the large glass-panel photographs. We put together one exhibition for the Leo Kaplan Modern gallery in New York City.

The collaborative pieces I did with glass artist Mary Van Cline were included in a showing of her work at the Leo Kaplan Modern Gallery in New York City. The largest piece was a 17′ Greenland kayak frame that I made of aspen wood and suspended by monofilament over three pieces of glass that echo the kayak’s shadows and sheer line. The New York office of a fishing equipment manufacturer almost bought the piece, but, alas, the kayak is now hanging in my basement.

Left: I began taking liberties with traditional forms and made traditional single-bladed kayak paddles with textured or wavy blades. This one has a bone tip and grip caps. Right: I made the model kayak frame in this piece as a straightforward representation of an East Arctic Inuit kayak documented by ethnologist David Zimmerly.

We did another exhibition in a Seattle gallery and made new works to be auctioned at fund-raising galas put on by the community of Northwest glass artists and their patrons.

My contribution to this piece was a modified partial Greenland kayak frame. I rubbed it with white paint to give it the look of bone. The piece was purchased by a San Francisco couple and was later a part of an exhibition at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts.

One of the pieces we produced was purchased by an art-collecting couple in San Francisco. The element I contributed was a model Greenland kayak frame with the chines and keel omitted and a pattern of curves carved into the deck beams. A few years later, selected pieces of the collection, including our work, was shipped to Boston for an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts. The young art student I once was might have preferred making it to the MFA as an artist, but I’m OK with making it there as a boatbuilder. There’s not all that much difference.![]()

Matt Morello

Matt MorelloWillits Ansel—painter, boatbuilder

With sympathy to Evelyn Ansel and her father Walt Ansel, and gratitude for their permission to use images of Willits’s artwork. The exhibition—Willits Ansel: Recent Works—at the Georgetown Historical Society in Georgetown, Maine, is open through July 10.

With this issue we’ve taken on a new name and a new look. We’ll still be doing our best to provide you with the most informative and engaging articles about small boats.

Thanks for the heads-up about the Ansel exhibit in Georgetown. Of course Mr. Ansel was intimately familiar with everything about half models. He might have laughed then, when in the early ’80s a MacDonald’s opened in Bath, up river from Georgetown. They made an effort to fit in with the shipbuilding history of the city by decorating the interior with “shippy” photos, wallpaper, and half models. Unfortunately several of the half models were mounted with the decks instead of the back of the half-hulls into the wall. It was a source of some amusement in town…for some.

I hadn’t known about Will Ansel’s death. In the summer of 1958 Will and I, both married and recently out of the navy, found ourselves the only students in the University of Virginia summer architecture school, trying to get a jump start on what was then a five-year professional program. Will and his wife Hanneli were living up in the hills about 25 or 30 miles outside of Charlottesville, Virginia, where he taught history at, and was the de facto head of, the Blue Ridge School for boys. Our daughter Gordon and their Walter were both toddlers and we all spent a lot of time together that summer and over the next couple of years, but as you might expect, Will didn’t take very well to the disciplined side of architecture and stayed on at the Blue Ridge School, where he dealt with the stresses of teaching at a nearly defunct boarding school by building a 20-something foot sailboat. I left Charlottesville to finish my architecture degree at Penn and Will, trailing his sailboat behind him, left the Virginia mountains for Madison, Wisconsin to get his master’s degree. They stopped in to see us in Philadelphia three or four years later while on their way to a teaching job in DC.

I went to work in England and then back to Virginia. I’d heard from a friend that Will was in Mystic, but by the time we’d retired to Connecticut, Will had moved on to Maine and our paths never crossed again.

When we did finally get to Mystic about 15 years ago, we ran into his son Walter, and saw Will again that same year at WoodenBoat School where I finally began work on my first wooden boat, 60 years after my introduction to the mysteries of wooden boatbuilding on a rainy evening in a steamy plastic-wrapped tent in his back yard in the mountains of Virginia.

I liked the forms of “art,” especially the watercolor of the dory skiff, the Greenland kayak frame, and the single-blade paddle.