It was July, and I was starting to feel claustrophobic. Surrounded by masked faces everywhere I went, switching sides of the street when I saw a neighbor coming, it seemed impossible to escape the pandemic. I yearned to be somewhere I could move freely without fearing human contact and breathe in cool clear air without restriction. The southern waters of the Salish Sea, which have drawn me back year after year, would be that somewhere. Its maze of narrow waterways doesn’t attract the boaters who crowd the San Juans and the Gulf Islands in the heart of the Salish, and offers many places so shallow that only small craft can travel there.

I trailered ROW BIRD, my 18′ Oughtred Arctic Tern, to Arcadia, a community of a dozen homes 11 miles north of Olympia, the state of Washington’s capitol. The concrete boat ramp there, usually busy with commercial shellfish boats equipped with dive gear and burly men in chest waders, was empty. Grateful for the solitude and the freedom to breathe, I felt surprisingly normal as I launched ROW BIRD. I set out late in the day, in that golden hour when the sun illuminates the water in long orange bands. With about three hours to make 5 nautical miles before dusk, and a steady sea breeze from the west rippling the water, I knew I’d make it handily to my first anchorage, Big Fishtrap, with time to spare.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

Whenever I launch at Arcadia, I always head between the undeveloped shores of Hope and Squaxin islands. The former a state park, the latter a Native American holding, both give a glimpse into the past with their mature, or even old-growth, conifer forest and occasional cinnamon-barked madrone trees. The nearest houses and docks were three-quarters of a mile away and enough out of sight to provide the illusion of wilderness. I skirted the Squaxin Island shore and made the half-mile crossing of the southern entrance to Peale Passage, passed the slender end of Harstine Island, and did a second half-mile crossing of Dana Passage.

I reached Big Fishtrap as shadows from its western headland were cast across its opening. I paused for a moment to make sure I was in the right place. For years, even passing by only a hundred yards from shore in a rowboat, I had missed its narrow mouth, which had always been obscured by a sandbar. Then, on one occasion, I saw two native fishermen stretching a gillnet at the entrance and realized the salmon they were after must be going somewhere, so I rowed in through the 50-yard-wide gap in the shoreline. Inside, the mirror-smooth water reflected the tall cedar and fir trees. Beneath the boat, scads of lavender sand dollars were scattered about on a sandy bottom. Their presence was a sign that the tide never receded past this point. The inlet splits like a crescent, with one arm leading a quarter mile to the south, the other curving a half mile to the east.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorFrom inside Big Fishtrap, I could look out past the sandbar toward the deeper waters of Dana Passage. No matter the weather outside, Fishtrap remains calm, and its shallow waters keep it from being crowded by larger boats.

Now, after just a single run and reach since the launch ramp, I headed toward the funnel-shaped entrance, gliding past the 42′ ferro-cement schooner PTERODACTYL moored at Fishtrap’s outer fringe. I tacked, aligning ROW BIRD with a dock and sandbar that mark the point where the entry channel narrows. A hundred or so feet offshore, I dropped my mainsail, furled the mizzen, and rowed through Fishtrap’s stream-like channel and into an utter calm and onward to a nook in the easterly arm. I set my anchor in 4′ of water, calculated that the tide would rise another 11’, and let out my rode. As I was unrolling my cockpit tent, a kayaker gliding by invited me to his house at the end of the east inlet for a cup of coffee and a shower in the morning, an unexpected and generous offer. A dog barked from a house tucked out of sight in the woods and a few crickets chirped nearby, otherwise the Fishtrap was absent of sound or motion. As the dark settled in, I felt smart and snug in this tiny anchorage, useless to so many bigger boats, but perfect for ROW BIRD’s shallow draft.

Inside Fishtrap, I pulled up my 9-pound Rocna anchor. An anchor that big may seem like overkill for a boat like ROW BIRD, but it provides me with peace of mind.

At first light I was ready to get underway. There was no sign of life at the kayaker’s house in the morning; I was too excited about going sailing to sit still over coffee anyway. I rowed out of Fishtrap at dawn into Dana Passage. A land breeze making the leaves of a shore-side tree flutter would push me eastward toward Nisqually Reach on the east side of Johnson Point, where I planned to meet up with my friend, Dan, at Zittel’s marina. The miles easily passed under ROW BIRD. I sat with mainsheet and tiller in one hand, a cup of hot tea in the other, passing vacation homes and enjoying watching the landscape broaden as I rounded the point and sailed into the wide-open reach.

The marina’s breakwater is a jumble of fractured concrete docks with yellowing grass growing out of the cracks and a raft of raw logs that look like splintered pick-up sticks. While people avoid the breakwater, harbor seals lie about there as if the place was made for them. As I arrived, a big trawler pulled in just ahead of me, and its wake rocked the breakwater, sending a dozen seals and pups scurrying into the water.

Dan investigates Baird Cove close to high tide. It dries to mud at low tide. His masts are down to make rowing easier.

It took me a moment to pick out Dan’s 19′ Ness Yawl, OTTER, among the jumble of masts, outbuildings, and covered docks. From a distance, I motioned him to follow me to the adjacent Baird Cove, a shallow inlet densely ringed with fir trees and nearly closed off by a muddy spit carpeted in lime-colored pickleweed. Dan rowed OTTER around a full circle taking in the landscape’s many shades of green. A bald eagle glided out from the woods, swooped down to the water, grabbed for a fish with a splash, but missed and alighted in a tree at the edge of the inlet.

“Where should we go?” Dan asked.

“Anywhere,” I said. “The wind is starting to fill in strong enough that we can buck any current the South Salish can dish up. How about visiting some mud?” That we’d “visit mud” was a foregone conclusion. Dan normally sails the northern waters where the shorelines are rocky. Here we’d find a lot of mud and a few patches of gravel.

After taking a break under mizzen alone, Dan raises OTTER’s mainsail as an afternoon breeze kicks up in Case Inlet.

We decided to aim for Dutcher Cove on the Key Peninsula side of Case Inlet, a snug anchorage where we could spend the night when the tide came up. With a 10-knot westerly wind, and little room for fetch to build up, we moved along briskly on a beam reach, sails full, but never strained. OTTER quickly took the lead. I fussed with sail trim and shifted my weight around, but ROW BIRD was outpaced.

OTTER is a foot longer than ROW BIRD, which, under a broad reach, makes her notably faster. Here Dan pilots OTTER near the lightly developed Key Peninsula.

The wind was steady so I cleated the mainsheet, leaned back in the cockpit, and enjoyed the breeze on my face and the motion of the boat beneath me. We had no schedule to adhere to; our transit of landmarks like McMicken and Herron islands marked the passage of time. Clouds rolled in from the west with the wind and, despite the season, I donned a ski cap and then my hood—the cool air a welcome respite from the 85-degree weather I’d left at home in Portland, Oregon.

Dan Murdoch

Dan MurdochAs we sail north past Herron Island, Case Inlet begins to narrow. An array of small harbors and inlets are perfect for shallow-draft boats. On a clear day, the snow-capped Olympic Mountains would be visible in the distance.

After nearly 7 miles of sailing since leaving the marina, we encountered the Herron Island ferry, the only boat we’d seen all day. Toy-like and bathtub shaped, it bumbled along, carrying just six or so cars on its deck, to the island a half mile from shore. Easily avoiding it, we continued sailing north as the wind grew.

By the time we reached Dutcher, which I had imagined would be an idyllic destination, the wind had shifted from westerly to southerly and waves were piling up on the beach. Dan hove-to, while I dropped the sails, pulled up my centerboard and rudder, and changed to oars to explore the shallows for a place we could pull ashore safely. I quickly ran aground on a mud bar, 20 yards from the beach, and had to shove off with an oar. Navigating around it, closer to shore, I stared up a long intertidal slope studded with rocks at the dry sand some 12’ above me. It would be hours until the tide would rise high enough for us to get into the cove or on to the beach. We had reached a dead end.

Rowing out to Dan, I noted a line where the wave-churned water changed color from stale coffee to a blackish blue. Once alongside, I shouted over the chop slapping our hulls, “Let’s go back to McMicken Island!”

Dan looked relieved. “Yes, let’s!”

Dan Murdoch

Dan MurdochWhen conditions allow it, I like to stand while I sail. It gives me a different perspective on the landscape and water conditions, often better than sitting down. Here, I’m keeping an eye on an approaching motor vessel.

In the South Salish, the 5-mile stretch to the cove at the south end of McMicken would normally be a few hours under oars, with the occasional zephyr teasing us just enough to raise sail, then petering out a few minutes later. But with the day’s unusually steady breeze, we bounced along over wind waves, trading tacks, competing to see who would reach McMicken first. On this point of sail, the boats seemed evenly matched, and only our sail handling made the difference. I started out in the lead, but lost ground when I came too close to shore and dragged my centerboard on the bottom, slowing ROW BIRD to a crawl. When Dan tacked too far off shore, I cut close to the beach again, and gained a few boat lengths on him.

Dan arrived at McMicken Island State Park just after I did. The area around the island has shallow clean water making it a clamdigger’s delight, though we didn’t have licenses or a good low tide before dinner to take advantage of the intertidal foraging.

As I approached the cove between Harstine Island and McMicken Island, the wind was on ROW BIRD’s nose. It felt futile to tack further. Wanting to be first ashore, I switched to oars, keeping an eye on OTTER in the distance. A few minutes later, ROW BIRD’s bow hit McMicken’s pea-gravel beach with a crunch; Dan was still tacking a few hundred feet out.

Despite spending most of the day on the water, and the sight of inviting picnic tables in a nearby sheltered meadow, Dan and I unrolled our dinner bags on the gravel, leaned back on a sun-bleached log, and cooked on the deserted beach, wanting to savor the light on the water. A few dozen boats could have fit into the cove, but only two besides ours were at anchor a third of a mile away.

For daytime stops, we use elastic Anchor Buddies to keep the boats nearby, but afloat just off the shore. At this beach near Harstine Island State Park, we tied both boats together and used one Anchor Buddy off the aft end of ROW BIRD. A bow line with an anchor on OTTER keeps the boats accessible from the beach. Commercial shellfish boats are in the background.

As we ate, the slender quarter-mile-long sand and gravel tombolo that connects McMicken to Harstine Island was slowly engulfed by the rising tide, making McMicken an island of its own again. OTTER and ROW BIRD bobbed gently, a light breeze holding them on their tethers just off the beach.

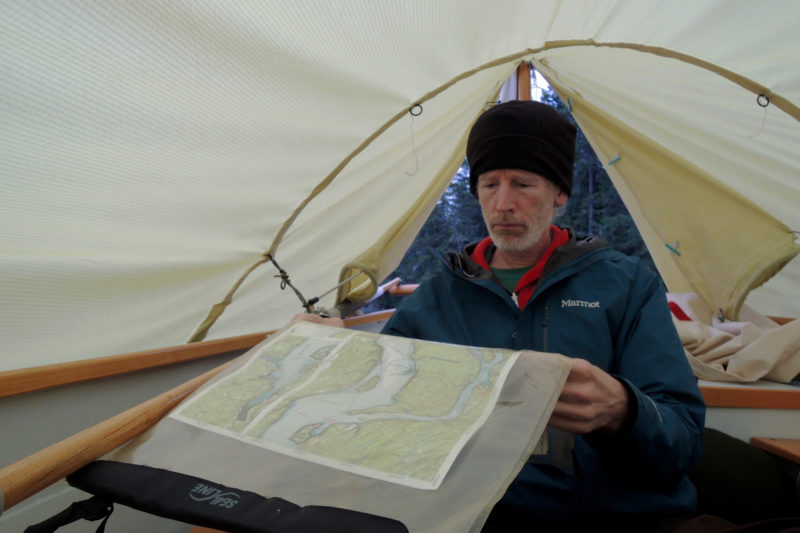

Once at anchor, I always erect my cockpit tent before the damp marine layer sets in. Afterward, I write down in a waterproof notebook the tide and navigation details I’ll use the following day.

At dusk we hopped back aboard our boats. The wind was strong enough to blow us into the cove without the need for oars, and we set our anchors and ensconced ourselves in our tented boats. Listening to the water lapping on ROW BIRD’s hull made me feel as if I were still underway. I leaned back and filled out ROW BIRD’s log for the day: “Possibly the best South Salish sailing day, ever.”

A gray dawn crept slowly up on us. Like me, Dan is a fervent sketcher, and we spent a lazy morning back on McMicken’s stony beach making ink drawings in our sketchbooks. It’s easy to keep moving continuously on a cruise, but a voyage that includes time for drawing helps me remember the details of a place, like the cross-hatched, golden pattern of the salt grass that sits atop a knee-high slab of vertical mud just off the beach. Its dark-chocolate-colored surface was riven with cracks, like the bottom of a dry lakebed turned on its side. Tiny salt crystals had formed in joints of the grass blades.

Keeping a log is a great way to record conditions about places worth visiting again on future cruises. Dan and I also like to include sketches. On the beach at McMicken Island, Dan drew the scene in OTTER’s log.

When the sun broke through the clouds, the flag on my mizzen—ROW BIRD’s insignia, a green silhouette of a tern in flight against a white field—began to flutter. Never one to waste wind, Dan motioned me to wrap up my drawing and get going. I wanted Dan to experience the muddy, critter-rich, and sometimes smelly inlets that make the South Salish unique, so we set a course for Henderson Inlet’s western shore to explore Chapman and Woodard bays, a pair of half-mile-long serpentine inlets surrounded by a 900-acre wildlife preserve.

As Dan rowed past a mudflat near the mouth of Henderson Inlet, clams and other invertebrates squirted water from the mud, which helps them get oxygen until the tide returns.

Approaching Chapman Bay, we saw commercial shellfish farmers tending their crops along the banks of Henderson. Tall PVC pipes marked the edges of their plot while rows of larger pipes protected young clams. Workers carried wide-mouthed plastic baskets to gather those that had grown large enough for harvest.

In the distance, beyond the shoreside homes and private docks, evergreen trees dominated the uplands. A jumble of pilings and a crumbling pier nearly one-third mile long jutted across the mouth of the bay. The pier, now disconnected from land, is all that remains of a once bustling timber business where trains dumped their cargo of logs into the bay to be gathered into rafts, then towed by tugs to mills farther north.

We rowed along the pier. Overhead, thousands of barnacles clung to every inch of the pilings, clicking and bubbling as they waited out the low tide. Herons and gulls perched on the creosote-stained timbers. We noted a large box installed as a home for bats, hoping we’d be able to watch a cloud of them emerge at dusk.

After poking into Chapman’s winding channel, carefully watching for strainers formed by fallen cedar trees, we rowed as fast as we could to ram the boats high on a mucky beach near the head of the pier. Dan and I stared at each other, wondering who would step out first and how deep he’d sink. I secured a small anchor and rode to a cleat, then crept to ROW BIRD’s bow. Extending a tentative boot toe into the mud, I immediately smelled a puff of sulfur but, surprisingly, encountered a solid layer of silt an inch or two down. I let out rode, carefully minding my footing, and set the anchor near a log firmly lodged at the high-tide line.

Once secure, we left the boats to dry down with the falling tide while we explored the preserve by foot. Here in the peaceful dappled shade, the only sounds were the wind and the birds.

“What are all those gulls cawing about?” Dan asked.

I looked up to the treetops and saw dozens of nests. “Those aren’t gulls, they’re herons.” Then, scoping the birds with my binoculars, I noticed their dark, long necks and realized that we were both wrong. The ruckus and the nests belonged to hundreds of cormorants.

With OTTER, seen here, and ROW BIRD at anchor adjacent to the pier at Woodard Bay Natural Resources Conservation Area, we were concerned that our anchors and rodes might get fouled on old logging equipment or sunken wood. We were fortunate and had no problems.

As the sun began to set, we anchored between the cormorants on shore and a set of abandoned docks so packed with mother seals and their pups that they listed at the ends. But while the cormorants had settled quietly for the night, the seals squeaked, mewed, and barked until dawn. Although initially annoyed by their cacophony, I soon fell fast asleep.

At dawn on my final day with Dan, I was excited to get moving before it got too hot. Dan was content eating breakfast and watching the fog drift across Henderson Inlet.

The next day, Dan and I rowed north and parted company at the mouth of Henderson Inlet. He would return to Zittel’s then go back home and to work, but I had one more day and night out. I’ve often thought that I could spend my whole life poking into crevices and tiny bays throughout the Salish Sea and never see them all; so, on this final day of my escape, I decided to investigate a few more that I’d only seen on a chart.

I caught the last of the flood westward through Dana Passage following the mainland shore past Big Fishtrap, Little Fishtrap, and then into Zangle Cove which, disappointingly, was lined with houses and exposed to wakes from a swarm of fishermen jostling for salmon. The day was sunny and warm—gone was the cooling west wind from earlier in the week—and I broke a sweat as I rowed south around a series of points toward the village and marina in Boston Harbor. I hadn’t been there in years and wondered if I’d missed any of its charms, but seeing rows upon rows of houses and the crowded marina, I immediately decided that keeping away from people was my best course.

After a lunch break in the shade of tall confers at Frye Cove, I pulled out my binoculars to watch a pigeon guillemot diving for fish. I also scanned the mouth of the cove to ensure that a shoal wouldn’t block my exit as the tide dropped.

My chart marks tidelands in a muddy green, and I steered for these places, recognizing that they are often improperly charted and can make for great small-boat exploring. Taking a leisurely course, I wound into Eld Inlet, enjoying a lunch-and-birdwatching break in the welcome shade of the woods at a park at Frye Cove.

As the shadows lengthened and the number of boats on the water dwindled, I found myself about a mile from my take-out. Still eager to stay on the water, I sailed slowly past Arcadia into Hammersley Inlet, recalling from a previous trip that there was a question mark-shaped slough, Mill Creek, about 2 miles in. I changed back to oars just past low tide. The entry, right across the inlet from Libby Point was only about 100′ wide and just deep enough to row without scraping my blades on the bottom. I moved just far enough in to be invisible from the main inlet, turned ROW BIRD perpendicular to the flow of the tide, and set a bow and stern anchor. With a copse of trees standing atop mudflat to one side and a tree-clad cliff to the other, I was pleased to find myself in a natural cathedral, not far from homes that hogged the shoreline just out of sight, yet a world away. Here in the shallows, with a ceiling of stars and walls of tall trees, I finished working in my sketchbook, read, and felt completely at ease.

I drifted off to sleep before the turn of the high tide. In the middle of the night I awoke to find ROW BIRD perfectly still. Had I landed in the soft mud at low tide? Or was this stillness simply the absence of waves? I could have been concerned that I had misread the tide tables and would be stranded in the mud, waiting hours or days for a rising tide, but I didn’t bother to look and just rolled over. Stranded or not, there was no place I’d rather be.![]()

Bruce Bateau, a regular contributor to Small Boats Magazine, sails and rows traditional boats with a modern twist in Portland, Oregon. His stories and adventures can be found at his web site, Terrapin Tales.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Excellent adventure! Thank you for writing it and allowing it to be published. We started our odessey at Olympia, ranging to the Broughton’s. It was only two years ago that we ventured up the “ditch” to Shelton. Great memories brought back to the fore by your tale.

It was interesting to me to see what cruising is available down south, as I have never ventured that way.

Thank you for sharing your trip.

Great story. Good looking boats, well used.

A wonderful recounting of a great trip. Growing up on the east side of Olympia, I’d bicycle out to the points of the peninsulas and explore by land the places you visited by sea.

What are this boats? They are quite lovely and practical.

Cheers to you both.

I really enjoyed the story. Thanks. Your chart added a lot to my understanding.

Hello, Ian. Thank you for the compliment on the map/chart. I enjoy making them and am glad that they help.

Was wondering about your boat. What are the attributes of this boat that make it good for this type of trip? How difficult is it to step the masts?

These sail-and-oar boats are great for this type of trip because they are shallow draft and have two very functional means of motion. While they won’t point as high as a dedicated sailboat, one can step the mast in seconds and be underway in a minute or two. The boats are also large enough that single person can comfortably sleep and cook aboard, yet they are small enough to store at home, and simple enough that they can be used as a day sailer too.

Nice trip and piece, Bruce. I forgot the ease of a boat that can go in such shallow water. My current 24′ , 3′-draft craft now has an alarm that goes off in 10′.

Very nice. What a pleasant, well-written account. Thank you for sharing this.

A pleasant, well-written account indeed! Seeing your sketches would be the cherry on top! Perhaps a follow up ? I really enjoyed this, thank you much for writing it!

Eric, thank you for the kind words about the article. I placed a few of the sketches from the trip on my blog, just for you. Please take a look. But if you’re as talented as the artist who shares your name, perhaps you should pass. 😉

Do you have any drawings of your tent set-up? What material are you using? Did you make it? I have a Tern and want to sleep in it.

Thanks