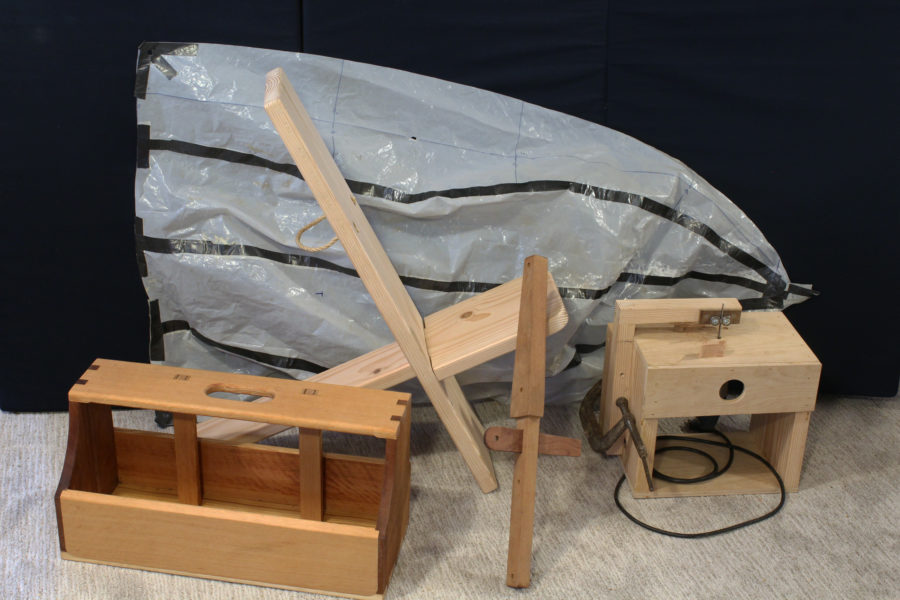

I almost didn’t go rowing yesterday. After spending too many long hours at my desk, I needed to get out of the house to clear my head. In the early afternoon, I studied the sky to the north through my home-office windows. Beyond the black filigree of leaf-bare tree branches, the sky was dimmed by a leaden overcast. The dull gray sky threatened rain and I balked at all the work it would take to get ready for a short afternoon row. I’d have to clear a path through scattered boxes and lumber to get the Whitehall out of the garage, gather foulweather gear, hook up the trailer and make sure the lights work, lubricate the locks and the oar leathers, and load a PFD and a fender aboard. I got busy and in about a half hour I was ready to drive to the ramp.The last thing I had to do before I backed the trailer into the waters of Seattle’s ship canal was put the rubber stopper into the Whitehall’s drain. It slipped in easily enough, but when I flipped the lever to expand the rubber for a watertight fit, the plug was still loose. I adjusted it several times, hoping this outing would be worth the effort.I didn’t need to wait long for the reward. The first three strokes left my lethargy in the Whitehall’s wake and returned me to a feeling of vitality that rowing had been giving me for decades. My hands had been at the keyboard and the mouse for days, and the pressure of the oar handles triggered in them an impulse to pull just as the pressure of a harness does to sled dogs and draft horses. I could feel the contact of the blades with the water not as vibrations of the handles in my hands but as if my sense of touch and proprioception extended to the blades themselves.

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.

Comments (6)

Leave a Reply

Stay On Course

Thanks, Chris. You’ve recharged the corporal memory of settling into my kayak along Lake Union or the canal. While walking brings daily joy and release, longing for moving in the ‘yak is revived.

Peter

Uplifting editorial, Chris. Thank you. I hope you get another twenty or thirty years of rowing. I think I began rowing a heavy wooden Whitehall-type boat on BC’s Sunshine Coast at age 5 or so. I took it up again at age 40, rowing out of Santa Cruz Harbor onto Monterey Bay in Daisy, a 13′ fiberglass pulling boat. After about twenty years my back succumbed to the damage from a teen-age injury and I moved into my 14′ power dory. I am tempted every now and again to rig her for rowing and see what I can do.

Give in to the temptation! While you are getting the boat rigged, consider doing some core stabilizing exercises for rowers. A session or two with a trainer or physiotherapist can get you started, or you can consult Dr. Google.

Thanks, Andrew. I have done plenty of physiotherapy on my back and core over the years but am still nervous about rowing again. I will give it a try.

Still in Santa Cruz? I grew up around the Pajaro Valley, but live in the Midwest now. I discovered skin-on-frame construction a few years back, and the weight reduction has made all the difference to my body, battered by combination of sports and career (military and law enforcement) stresses. On top of that, I find skin-on-frame boat building even more fun than ever, if that were possible. Take a look at Dave Gentry’s offerings or Kudzucraft (Jeff Horton), as they seem to me to be the easiest way into this construction method. I will be visiting family and friends in October, though I won’t be bringing a boat.

Thanks for the inspiration, Chris. Indeed..it’s high time to get my little 14′ Whitehall back in the water!