When my wife and I decided to start cruising together, we acquired a 19′ Phil Bolger–designed Chebacco gaff cat-yawl and quickly realized that we’d need to find a dinghy as well. Although it will float in a foot of water, the Chebacco’s weight and bulk make shore landing more challenging than we are used to in either our Oughtred Arctic Tern or Adirondack guideboat, both of which can be easily beached. Moreover, we cruise the tidal waters of Oregon and Washington, where the possibility of being stuck aground in an outgoing tide makes it prudent to anchor out and row ashore.

The first season we towed a plastic sit-on-top kayak. It was easy to transport and light enough to carry solo, but it was a wet ride, had no cargo capacity, and was challenging to climb aboard from the Chebacco.

The following winter, I researched other lightweight options, including an inflatable packraft, as well as some plywood boats like the Nutshell Pram. I eliminated the packraft because it seemed it would sit low in the water and be another wet ride. While the Nutshell is a proven design, at 90 lbs it would be too heavy to lift and carry by myself.

Upon further research, I discovered the 6′ 8″ by 3′ 8″ Portage Pram, available as a kit with CNC-cut plywood parts and having a finished weight of 35 lbs. I borrowed a completed pram that a friend had built, and after a few minutes at the oars I realized that its combination of light weight and good handling would be perfect for our needs.

Photos by or courtesy of the author

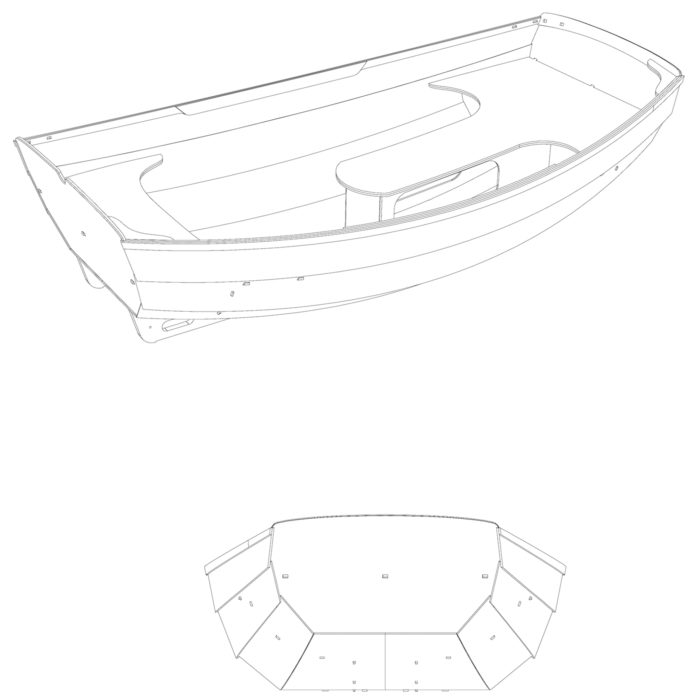

Photos by or courtesy of the authorThe design of the Portage Pram has been updated to include a foam gunwale sandwiched between two pieces of plywood. Bulkheads under the seats fore and aft create sealed flotation compartments, which can also be used for dry stowage if access hatches are added.

The Portage Pram was originally designed for solid-wood construction in the 1970s by Bill Peterson at Murray G. Peterson Associates. Duckworks Boatbuilders Supply prototyped an ultralight plywood version in 2017 and soon after began selling kits. (Recently, Duckworks started offering a sailing version of the kit.)

The rowing-only kit I ordered arrived in a flat-packed crate approximately 7′ × 2′ × 3″. All pieces were precut and required only minor sanding. A 190-page digital manual, illustrated with color photographs and drawings, guides builders through the steps of construction. The manual was helpful, although it was last updated in 2021 and did not represent all aspects of the latest updates to the design (and could be edited for brevity). As an example, the manual showed a previous version of the gunwales, which were composed of 6mm plywood inwales and outwales supplemented amidships by shorter inwale doublers, each made of two layers of 6mm plywood laminated inside the inwale. The kit was delivered with an updated gunwale construction: closed-cell foam pieces to be encapsulated in plywood strips and fiberglass to create a curved bow-to-stern box beam.

Even when a few pounds over the design weight of 35 lbs, carrying the Portage Pram to and from the water is an easy task for one person.

The pram is initially assembled with zip ties, using the stitch-and-glue method. Its benches have precisely cut tabs that connect to slots in the hull. The chines are filleted with thickened epoxy. The gunwales, lower chines, and entire bottom of the pram are covered with fiberglass for strength. Building the pram is straightforward and involves basic woodworking tasks, such as trimming plywood, drilling holes, applying epoxy, and sanding. This makes it an easy project for first-time builders. I spent about 60 hours on the construction, with some extra time figuring out how to assemble the foam-cored gunwales.

The completed pram has a comfortable 11″ × 32″ aft bench. A 40″-long T-shaped forward bench, along with two sets of oarlocks, allows a rower to shift as needed to balance a second person or heavy load in the boat. The 8″-high benches sit atop sealed compartments, each providing about 1.5 cubic feet of flotation or dry storage if ports are added for access. No floorboards or foot braces are specified in the plans. The recommended oarlocks are tubular plastic sleeves installed vertically through the gunwales.

My boat weighs 43 lbs, including a stainless-steel pad-eye for towing, two nylon cleats, two pairs of bronze oarlocks, and two watertight plastic inspection ports. Even as a middle-aged man, I find the pram easy to load onto my car’s roof rack or roll up a beach on a fender. Carrying the boat solo from car to shore is easy.

Trim is all-important in the Portage Pram. With a single rower onboard the twin skegs are not fully submerged, but despite this the boat still holds its course well. With a passenger seated in the stern, the skegs provide excellent directional stability.

Getting in and out of the pram from a dock or a boat is like climbing aboard a large canoe. The pram can slide horizontally if I don’t place my weight in its center but overall is fairly stable. Due to its flat bottom, it rolls very little, especially when we climb aboard or adjust our weight while seated. When using the pram solo on flat water, I find it stable enough to stand up in. It can comfortably hold two adults, a full 3-gallon gas can, and a bag of groceries.

Although no oar length is specified in the plans, I used the Shaw and Tenney oar-length formula and made 6′ 6″ straight-blade cedar oars, which are effective and stow flat on the seats while towing. The two rowing stations function well as designed, and the boat balances nicely, with one or two aboard. At 6′ 1″, I am unable to fully stretch out my long legs when I’m rowing at the center station with my feet braced against the aft bulkhead. When I’m rowing at the forward position, I just rest my feet on the lower strakes. Although I prefer foot braces in a rowing boat, I do not miss them in the pram because their absence keeps the boat light, and I only use the pram to travel short distances. The boat rows comfortably at around 2 knots; at faster speeds the oars and bow splash, getting me, and the inside of the pram, wet. There is a sculling notch in the transom; it works, but with a 6′ 6″ oar, I find it challenging to use while maintaining good trim by squatting near the aft thwart.

The forward seat allows the rower to shift his weight into the bow and thus trim the boat to comfortably carry a passenger. Unusually, for a boat of this size, the pram has two rowing positions, allowing for correct weight distribution.

The pram tracks well with one person aboard, and even better with two. While rowing solo, the rocker allows it to turn quickly and playfully, but it never turns without my choosing to. With a second person aboard, the two skegs on the aft end are better engaged with the water and keep the boat going straight, even in a strong crosswind. The pram tracks and rows comfortably in winds up to about 10 knots; however, splash and spray come on board more often when there is any kind of chop or wake. Surprisingly, while towing it through 2′ to 3′ chop or in crosswinds, the interior can remain almost entirely dry.

When under tow behind the author’s 19′ Chebacco, the Portage Pram tracks well, following politely whether going straight or turning. Even with a bit of chop or swell, the pram stays dry and upright.

The pram is impressively well mannered when towed by our Chebacco under sail or motor. It follows our track whether going straight or turning, and whether the water is choppy or smooth. Even when faced with multiple large wakes from passing trawlers, the pram rises without tipping or taking on water, then resumes following behind. It never surges forward during rough conditions, threatening to hit our sailboat.

For such a small and light boat, the Portage Pram carries a substantial load and has the stability of a larger craft. Aside from the occasional challenge of keeping it from hitting our sailboat while boarding and deboarding the pram’s easy manners make going ashore elegant and fun.![]()

Bruce Bateau, a regular contributor to Small Boats, sails and rows traditional boats with a modern twist in Portland, Oregon. His stories and adventures can be found at his website, Terrapin Tales.

Portage Pram Particulars

Length: 6′ 10″

Beam: 3′ 8″

Weight: around 35 lbs

Portage Pram kits are available from Duckworks for $1,099.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Are plans only available?

Duckworks implies that you can buy plans, but I could not find anything besides the kit on their website.

Billy Atkin designed a similar little pram that he called “Tiny Ripple,” which was one of the designs in the MoTorBoaTing Ideal series. His was only 6′ long. It had only single plank (i.e. no topside curvature) flaring topsides, instead of the rounded configuration seen here. Atkin always argued for flare–sometimes extreme flare–on the grounds that it increased safety and secondary stability. He claimed that this tiny boat could function as a life boat, with watertight compartments at bow and stern. I never put it to the test.

I quickly realized that the full thwart across the stern made it very uncomfortable for rowing from the center station (even though I am not a tall guy), so I made the aft seat narrow enough that I could comfortably plant my feet against the stern transom. And I built mine out of 1/4″ fir plywood rather than the solid cedar planks Atkin called for. Had Brynzeel or one of the other high-quality marine plywoods been available at the time I would have used something around 4 mm in thickness, thereby saving weight. I made a finger slot in the forward edge of the little stern seat, which made carrying the pram upright the easiest way.

I towed the dinghy behind my little 21′ Ed Monk Sr. cutter all around the San Juan Islands. One time, sailing with a fresh breeze on a broad reach up the Strait of Georgia into swells rolling down from the north, the dinghy was planing with a taught towline. A pair of dolphins picked us up briefly, then one of them dropped back to check out the dinghy. Both the cutter and the dinghy seemed to come alive and did a lively dance in that rare, perfect combination of wind and waves. One of my most cherished memories.

I was always pleased with the rowing qualities of Tiny Ripple. It tracked quite well, even with a small single skeg, and went almost as easily with an extra crew member. In the harbor, I could easily outpace the little Livingston dinghies of similar size. I built at least two of these, including one for my dad. He used his for fishing in the small lakes around Lake Chelan in Washington state, often taking my mother along. I believe he sometimes made it go with a small electric outboard.