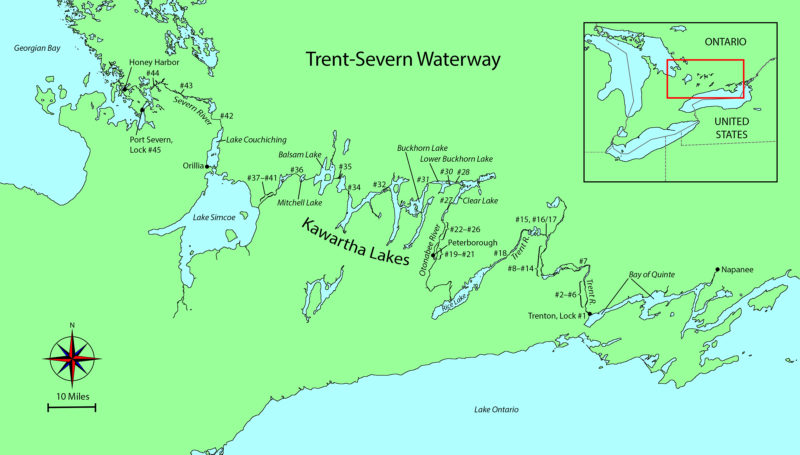

In 2018, I left my home dock on the Napanee River in southeast Ontario and headed for the Trent-Severn Waterway, a 240-mile chain of rivers, lakes, locks, and canals leading all the way to Lake Huron’s Georgian Bay. My challenge would be to do this trip solo in SOL CANADA, a small wooden boat I’d built to be 100 percent solar-electric powered.

I knew of only one solar-electric boat that had traveled the full distance from Lock 1 in Trenton to Lock 45 in Port Severn, so they were the first. I’d be the first Canadian using only the sun to charge my batteries.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorSOL CANADA’s canopy would not only keep me out of the sun and rain (mostly), but the four solar panels it carries would also generate all of the power I’d need for the trip.

SOL CANADA’s hull was based on the Greavette Dispro, manufactured by the Disappearing Propeller Boat Company from 1915 to 1958. An enclosed motorwell holds a Torqeedo Cruise 2.0 electric outboard, and in a compartment under the seats are four 6-volt batteries wired in series to provide 24 volts with a capacity of 221 amp-hours. I expected the boat to be capable of an average speed of 5.4 mph. The batteries are charged by four flexible solar panels on the canopy. They have a rated output of 860 watts.

At 7:30 a.m. on the morning of August 19, I motored away on what was supposed to be a sunny day with a light following breeze from the east. I headed down the 6-mile stretch to the mouth of the river, then along the Bay of Quinte to the city of Trenton—a distance of 31 miles.

There was a haze in the sky that cut the solar production by half, but on the bay, the easterly breeze was now a 12-mph tailwind and SOL, doing a bit of surfing, made good headway to the mouth of the Trent-Severn waterway at Trenton.

Two miles north upriver, the only boat heading upstream, I arrived at Lock 1 and went through immediately. The lockkeeper notified the next lock, just 3/4 miles away, that I was coming and its gate opened for me as I approached. There are three more locks in the first 6 miles of the Trent Canal, and all of them were expecting me with the gates open.

By the end of the first day of my trip, I had traveled 42 miles and had made it all the way to the top of Lock 5. With my home-made fabric walls rolled down into camping mode, SOL CANADA was ready for peaceful night’s sleep.

At 6 p.m. I motored out of Lock 5, well ahead of schedule. My total distance that day was 42 miles and my battery bank was at a 77 percent charge, good enough to carry me the next day if the conditions were poor. I was the only boat stopping for the night in a still-water cove above the lock. The lock master gave me a key to the staff washroom, kitchen, and the shower. Back at SOL, I prepared for the night by folding the seats down to make my bed and rolling down poly-tarp from the perimeter of the canopy. My enclosed sleeping quarters would get some peculiar looks, but they proved to be very comfortable.

On the morning of the second day, just north of Trenton at Lock 5, my good friends Ed and Sandy arrived by canoe to bring me a hot coffee and a homemade muffin. They just live 1/4 mile up river and frequently paddle this stretch of the Trent River.

The morning sky was clear, and the sun quickly warmed SOL’s enclosure. Ed and Sandy, old friends who live close by the lock, arrived by canoe bringing coffee and a muffin. After saying goodbye and packing my things, I rolled the curtains up and SOL was ready to go. It was such a sunny day, I figured I could maintain a good pace without drawing the batteries down. I got to Lock 6 at Frankford before the morning got busy with boat traffic.

All along the river, weeds choked the shallows, and islands of free-floating weeds ripped up by boats clumped together on the surface. I can see the power gauge jump when weeds get pulled in between the prop and the housing. Although I’d made a prop guard, weeds were still a problem, but I could throw the motor into reverse and almost always shed them. Sometimes I’d have to stop and tear them out.

When I emerged from Lock 6 at Frankford under a bright clear sky, the lock opened on water foul with weeds. Just 1/2 mile ahead they’d bring me to a stop.

Just past the Frankford lock, in a narrow quiet channel with cedar trees hanging over the bank, I felt the motor vibrate with weeds tangled in the prop. Shifting into reverse did not get rid of them, so I put the controller into neutral. As I removed the weeds, I did not notice that the breeze had pushed me close to shore. When I realized what was happening, I quickly twisted myself back into my seat to take control, and in my haste my elbow hit the throttle. The boat lurched forward into overhanging branches, and the 100-lb canopy came crashing down beside me. My shouts echoed across the channel. I should have pulled the magnetic kill switch before working on the prop.

I thought the trip was over. I made my way back to Lock 6 where two lockkeepers and a boater lifted the canopy up while I reinserted the front posts and drove screws back into the holes they’d been torn out of. One solar cable at the back had been pulled apart, and I had to splice it back together. After two-and-a-half hours, the boat was a bit battered but operational. I could keep going forward.

My packs containing my supper provisions and gas stove were on the picnic table as my boat was moored for the night at the top side of Lock 8, Percy Reach. After eating, I finished the repairs to the canopy supports.

I finished the day at Lock 8, a quiet site with campsites. I removed the screws that had been torn out, added glue to the holes, and reinserted the screws. I cooked up some spaghetti on my camp stove and was in bed by 9 p.m.

Morning came with heavily overcast skies; the forecast called for rain later in the day. So much for getting ahead of schedule.

I reached Lock 9 before its keepers arrived at 9 a.m. While I waited, I walked around the grounds. Set between farmlands to the east and a wooded island to the west, it would have been a very peaceful place to spend a night. Like many of the locks on the lower part of the Trent, this one was isolated from towns, their bridges, and their traffic. When the staff arrived, I spoke with the lock master; he mentioned he had a friend named Peter who was an editor and interested in stories for an online newspaper. I provided my phone number in case he wanted to do a story on my boat.

Just 1-1/2 miles upstream from Lock 9, I passed through Lock 10. Locks 11 and 12 were piggybacked one on top of the other for a combined lift of 48’. After about two hours on the water, with the rain pouring down and driving in from the starboard side, I got a call from the editor, Peter Fisher, and arranged to meet him the following morning. After seven locks and 12 miles in the rain, I arrived at the top of the two-lock flight of Locks 16 and 17. Lock 17 was not the nicest place to stay. The washroom was on the grubby side and the weather put me in a bad mood.

In the morning ,I had time to kill before meeting with Peter at 11 a.m. When he arrived, I invited him aboard for a ride on the boat as he interviewed me. I was back on my way at about 1 p.m., headed for Lock 18, 15 miles upstream.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

The sky was overcast and the solar panels would not be generating much power. I’d have enough charge to get to Lock 18, in the town of Hastings, more than 14 miles upstream; but the following day, to cover 37 miles to Lock 19 at the outskirts of the city of Peterborough, I’d need to start out with fully charged batteries and have sun along the way.

As I was approaching Lock 18, a motoryacht, NEPENTHE, passed by and entered the lock ahead of me. After exiting, we both docked at the concrete wall on the north side of the river. NEPENTHE’s owners, Paul and Jill, and their passenger Tom, are “Loopers,” traveling the 6,000-mile-long Great Loop, a chain of waterways passing through the U.S. and Canada via the Mississippi River and the Intracoastal Waterway. Dale and Ann aboard UTOPIA, another yacht stopped for the night, were also Loopers. For dinner, the six of us walked to a nearby eatery . The yachters asked if I had seen a kayaker named Steve who was paddling the Great Loop. I hadn’t, but said I’d keep my eyes peeled for him.

When morning broke, the day promised to be mostly sunny, just what I needed to get to the Peterborough lock. I left just past 8:30 and headed 5 miles west to Rice Lake, a 20-mile-long shallow lake that can be very rough when a stiff westerly blows, exactly what I faced that morning. SOL crashed over the waves, and the wind howled and made the canopy sway. The quiet electric motor made noise of the elements seem so much louder.

After 17 miles on the lake, I turned north into the Otonabee River where I found shelter from the wind, even though I was traveling against a strong current of about 2 mph. At the Bensfort Bridge, 7 miles upstream, I met with another reporter, Jason Bain, of the Peterborough Examiner. The riverbank where he was standing was rocky, so I anchored 30′ from shore for the interview. We talked for a while, and as I was getting ready to leave, I tried to pull the anchor up, but it wouldn’t budge. I had to cut the rode. Jason felt bad that I had to lose the anchor and promised to replace it.

It took me about 4 hours to make my way to Lock 19 into Peterborough and the lockkeeper there presented me with a new anchor and rode left for me, courtesy of the Peterborough Examiner. Jason called; I thanked him and told him the story of the anchor. In 1964, my father was working on a hydroelectric plant at Niagara Falls. A coffer dam constructed above the falls exposed the riverbed, and among the artifacts lodged in the rocks were two anchors. My dad brought them home and the one I’d lost was one of them. Jason felt even worse that the anchor was a family heirloom, but month later, when I was back at home, Jason called again. Two SCUBA divers had heard about the missing anchor, found it snagged, and sent it to me.

Just 3/4 miles up from Lock 19, I stopped for the night at Lock 20 in the middle of Peterborough. My cousins Carl and Melba took me out to dinner.

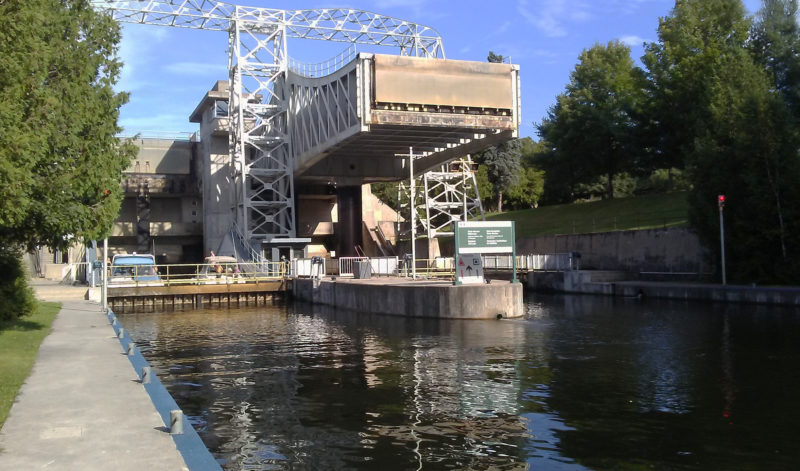

With my cousin Carl aboard, we motored into the Peterborough lift lock, Lock 21. This is the largest of its type in the world, and lifts boats 65′ in a just a couple of minutes. At the top there is a panoramic view of the city of Peterborough.

In the morning, Carl joined me to ride up 65′ at Lock 21, the Peterborough Lift Lock, the largest hydraulic lift lock in the world. The locks are a side-by-side pair of 140′ by 33′ tubs called caissons, each sitting on top of a cylindrical ram, 7-1/2′ in diameter. When a caisson reaches the top, it stops a few inches below the water level of the upper canal and takes on water when the gates are opened. The additional water makes it the heavier of the two, and as it descends, water in its ram flows to the other ram to drive the lower caisson upward.

After the lift, I left Carl at the docking wall and chased after the other boats leaving the lock to join them in the 4-1/2-mile-long succession of five locks. If I fell behind I’d have to wait for the next opening, so I zipped along at 5 1/2 mph, figuring I could spare the extra batteries power.

About 14 miles from Peterborough, Lock 27 was the end of the Otonabee River and the entry to the Kawartha Lakes, a chain of a dozen lakes traversed by the waterway. The lock is in a park-like setting with a 200-yard-long island separating it from the rapids and dam where the Otonabee River rushes by.

After another good night I arose to yet another overcast day. I set out northbound on Clear Lake turned west at Stony Lake and passed through two of Lower Buckhorn Lake’s locks, finishing up at Lock 31.

By now, the interview with Jason had been published and I was hailed by boaters and people on shore. People in cars honked and waved at me.

At the west end of Lower Buckthorn, I arrived at the downstream side of Lock 31 and secured the last spot on the wall. It was a Saturday and there was a festival around the lock with live music. I made the rounds until the rain started and I retreated to SOL for the night.

On Sunday morning I headed south along Buckhorn Lake, a 1/2-mile-wide wooded corridor dotted with summer homes and bristling with finger piers. The water is utterly clear but looks black where it is deep. The land around the lake is blanketed with tall pine trees and dotted with granite outcroppings. The waterway turned west through a cluster of undeveloped islands and then north along Pigeon Lake. By midafternoon I reached Lock 32 at Bobcaygeon, a little town in the middle of cottage country. I’d only traveled 17-1/2 miles, but the next lock was another 18 miles away, more than I wanted to take on.

Bobcaygeon was a beautiful spot to stop for the night. There were lots of people around while I tied up the boat, many of whom had read about my adventure in the paper and asked about SOL. I took a walk around town and when I returned I saw a lone kayaker in the lock, his decks loaded with gear. I yelled down, “Are you Steve?”

“Yes,” he answered. I had found the kayaker paddling the Great Loop. After he left the lock, I gave him a hand unloading his gear and helped him set up camp. Steve Chard, 60 at the time, is from England, and had served in the ’70s on British nuclear submarines. We went out for supper and he told me about spending the Cold War years aboard a sub.

On Monday morning, Steve got a 30-minute head start on me, and it took me a couple of hours to catch up and pass him. We were both planning to go to Lock 35, in the rural community of Rosedale, for the night. I arrived at the lock well before he did and as I waited for the green light to enter, I heard the lockkeeper on the loudspeaker call out, “Come ahead, Phil.” Word of my journey had spread and I was now getting personal service.

I set up for the evening above the lock, which is far from any town and hemmed in by old trees, but not necessarily primitive: it had showers and free wi-fi. Steve arrived, set up camp, and we cooked supper together—a spicy Uncle Ben’s rice dish beefed up with a package of partly dehydrated steak chunks. Our meal was interrupted by our cell phones sounding a weather alert: there would be a tornado watch for the next few hours. When the rain started coming down, Steve and I took shelter. We soon had plenty of company. The all-clear notice came at midnight; Steve headed back to his tent and I got aboard SOL.

In the morning, I headed out onto Balsam Lake for a 5-mile crossing. The wind was blowing from the southwest at about 18 mph. The marked channel was exposed , so I veered north to take shelter in the lee of Grand Island, a mile-long, sparsely inhabited island in the middle of the lake. That was fine for half of the crossing, but west of the island, beyond the lee, whitecaps splashed over the bow. I slowed down to limit the spray. At the end of the crossing, with only 1/4″ of water in the bottom of the boat, I entered a quiet, 30-yard-wide canal.

After crossing the very rough water of Balsam Lake on my 10th day underway, I entered into a very long stretch of hand-dug canal where some of the original tailings still remain piled high on the banks. I was relieved to be out of the strong west wind that plagued me on the lake and have this peaceful canal all to myself.

Two long stretches of canal here—separated by the 1-1/2-mile crossing of Mitchell Lake—were dug by hand, straight as an arrow, just wide enough for two boats to pass. Mounds of stone piled by laborers along the banks well over a century ago are still there. I savored the solitude and silence. The only sound SOL makes is the murmur of her bow waves.

Lock 36 is the Kirkfield Lift Lock, slightly smaller than the one in Peterborough, and SOL, the only boat locking through, was dwarfed by the 140′-long caisson. After the gate closed, we dropped 49′, the first descent after gaining about 600’ in elevation since leaving Trenton. The rest of my journey would be downstream.

After I exited the Kirkfield lift lock, the caisson on the left took on two boats and had its gate closed behind them, ready to be raised.

UTOPIA was moored for the night at the downside wall, so I pulled in astern. Dale and Ann invited me aboard, and while we were swapping stories, Steve emerged from the lock and paddled over to join us for barbecued bratwurst.

Steve was in the lead as we approached the Gamebridge Lock 41, the last lock before heading out onto the sometimes treacherous Lake Simcoe.

Steve and I set out from Kirkfield and descended five locks over 11 miles of canal, stopping at Lock 41, which lies just 1-1/2 miles from Lake Simcoe. A sign at the lock warns boaters to be wary and check weather conditions prior setting out on the 14-mile crossing of the lake. Its shallow depth and broad fetch can make it extremely hazardous, with waves that can reach 6′. Steve and I planned to be on the lake by 7 a.m., before any wind came up. I’d follow the channel right out to the center of the lake; Steve would paddle along the shore, which would take considerably more time.

I entered the lake under a dark, overcast sky with a northeast wind already starting to blow. With SOL running at 4-1/3 knots it would take 3-1/2 hours to reach shelter in the waterway through the city of Orillia. As I made my way farther into the lake, the waves grew, probably only about 2′ high, but they pitched SOL back and forth. The canopy was swaying, and to stabilize it I braced with my legs and held on to it with my left hand, like a guy driving down the highway, holding a mattress on the roof of his car. I slowed down to about 3-3/4 mph to keep breakers from crashing over the foredeck. By the time I got to Orillia, my legs were like rubber, but SOL hadn’t taken on too much water.

Beyond Orillia, I navigated a narrow gap into Lake Couchiching, a 10-mile passage, but in that narrow lake the water was merely choppy. In just over two hours I was across and headed up 1-3/4 miles of canal to Lock 42, nestled in a dense forest of white pine, beautiful and quiet. The wind blowing through the trees rustled of the needles and imparted a fragrance to the air. Steve sent me a text saying his trip around Lake Simcoe had been slow and he would spend the night in Orillia.

After I passed through Lock 43 at Swift Rapids, I could see the magnificent structure of the lock and the hydroelectric dam adjacent to it.

Just 32 miles separated me from Lock 45 at Port Severn, the gateway to Georgian Bay. Going downstream now, SOL was at times making 6-1/4 mph. Only two locks remained. The towering Lock 43 at Swift Rapids lowered me 46′, and Lock 44 at Big Chute is not really a lock but a marine railroad. A huge flatbed car on train tracks rolled down a slope into the water, and I drove SOL over it, stopping over a pair of slings that cradled the hull. The car carried SOL and a handful of other boats 185 yards over a rocky hill to the other side and back into the water. The ride was a bit bumpy and not as fast as a lock.

The so-called Lock 44 at Big Chute is actually an overland marine railroad, the only one on the Trent-Severn waterway. The adjustable straps can securely hold almost any hull shape, but even so it is a bit of a bumpy ride. (This picture is from is my second visit, on the return part of the trip.)

I cruised the final 8 miles through a chain of irregular lakes to Port Severn, where I tied up for the night at one of the docks near the entry to the lock.

On a beautiful Saturday morning I lined up for the lock before 9 a.m., bound for Honey Harbor. After passing through, I entered the channel, threading between countless islets and rocky shoals on the fringe of Georgian Bay. A dozen miles north, I arrived at Honey Harbor, and after a stop for a lunch of a burger and fries, headed back to Port Severn. There I tied up near a harborfront restaurant for the evening. Thunderstorms were predicted, and while I was in the restaurant the storm hit. Forked lighting struck all around, one flash and thunderclap after another.

I waited until the storm passed before returning to SOL for the night.

My plan for the next day was to start my journey back home along the way I’d come. I was now about three days behind schedule, with unstable weather predicted for the next four days.

I headed out in the morning under an overcast sky and a destination of getting to Lock 43, Swift Rapids. The sky cleared and by the time I got there it was a sunny, hot day. I moored at the top side of the lock and set up camp. The weather forecast for the coming days was not encouraging, and I’d surely have trouble on Lake Simcoe on my return crossing. I decided I would go only as far as Washago at the north end of Lake Couchiching and have my son-in-law pick me up there at the Washago town dock.

SOL had navigated 337 miles in 16 days, and I had reached my goal of traveling solo up the entire Trent Severn Waterway from Lock 1 to Lock 45 using 100 percent solar energy—a first as a Canadian and a first for a solo skipper. I’m happily satisfied with that.![]()

Phil Boyer retired in 2017 after working 38 years in R&D in the telecommunications industry. He now keeps busy teaching karate at two local clubs and building boats. He has been around boats his whole life, starting with paddling as a kid. At age 11 he built a sailing pram with a bit of help from his father. In 2006 he began building solo canoes and now has four of them, featured in the August 2019 issue. Phil’s interest turned to building SOL CANADA, his solar-electric boat, in 2015. His next build will be a solar-electric version of the Power Cat he read about in the March 2016 issue of Small Boats Magazine.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Quite a nice journey. Thank you for sharing. This home-bound old skipper really enjoyed your account of a journey few of us know about.

Thanks James, I am glad you enjoyed it. The Trent-Severn Waterway is a very unique system of man-made canals, lakes and rivers. It is also one of the routes taken by the Loopers, whom you see a lot of.

Congratulations, Phil, on making that fantastic trip through the great Trent Canal System with your solar-operated craft you built. We were so happy to meet you at the locks in Peterborough and have dinner with you. My family were happy to see you and I was pleased to be able to travel up the up those famous lift locks with you. What a great voyage for you.

Your cousin, Carl

Hi Carl,

Sorry for the late response. I enjoyed meeting up with you and Melba and Tod and the kids. Going through the lift locks is a bucket-list experience for sure. The whole trip is one I will always remember.

Great read. I thought I was there. Thank you.

Thanks, Perry. I am glad you enjoyed it.

I really enjoyed your trip. This was one of the few that I have followed all the way thru, and filled with much information. I am on the Gulf Coast and would love to take a trip up the Mississippi River one of these days, and would keep a running dialogue such as yours. Thanks for the journey and keep on tripping.

Ron

Hi Ron,

Glad you enjoyed the ride. The Trent-Severn is a beautiful waterway system. I hope you get your wish and do the Mississippi. A friend of mine kayaked down the Mississippi.

Enjoyed reading, and looking forward to my own retirement (25+ yrs to go) when I can do trips like this. I really love the story of your anchor, and that you got it back – adds so much to the history of that family heirloom.

Thanks Joshua, glad you enjoyed the article and 25 years will go by too quickly.

Great article but wished you’d had included details about electrical usage, state of charge and discharge of each day.

JD