Chesapeake Light Craft

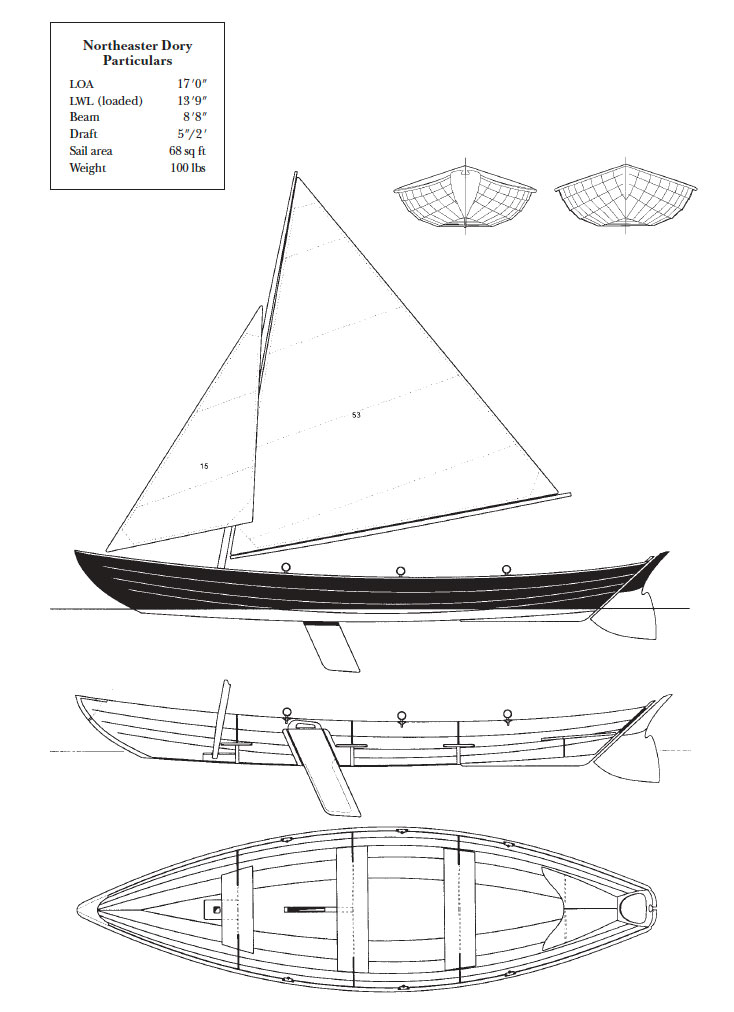

Chesapeake Light CraftThe Northeaster Dory is a glued-lapstrake-plywood interpretation of the Banks dory. It is available in kit form from Annapolis, Maryland-based Chesapeake Light Craft.

The Northeaster Dory from Chesapeake Light Craft is a contemporary interpretation of the classic Banks dory, a boat of great load-carrying capacity that’s initially tender, but stable when rolled to one side or the other. There is a wide range of dory types, from the husky Banks models that traveled on the decks of fishing schooners and were used to handline for cod; to the sleek, round-sided recreational type used for racing on Massachusetts’ North Shore; and on to the transom-sterned, outboard-powered models that shed some of the type’s signature characteristics but retain unmistakable lineage.

John Gardner recorded the history of the dory in his The Dory Book in 1978, tracing it back to murky origins nearly 500 years ago. This is the definitive work on the dory type, and in it Gardner states with clarity that it is materials and methods, and not hull form, that makes a dory a dory: “The dory,” he writes, “…is a wide-board type. And if it is not the only wide-board type, it is among the foremost, for dory construction is one of the easiest, quickest, and cheapest methods yet devised for utilizing wide-board lumber in building boats for a wide variety of uses. It should be well understood that it is the dory’s special mode of construction, not the hull shape, that sets it and its related sub-types apart from other boats.” After a short, pithy first part covering history, The Dory Book presents us with a primer on construction, and then a series of chapters presenting plans, histories, and descriptions of several different dories.

Chesapeake Light Craft

Chesapeake Light CraftChesapeake Light Craft invented and patented the LapStitch method of boatbuilding, whereby a rabbeted plank seam (visible here) replaces the standard bevel of lapstrake construction. The panels are wired together, and epoxy fills the resulting long gap.

The Dory Book provided a point of departure for designer John Harris, proprietor of the Annapolis, Maryland–based Chesapeake Light Craft (CLC). CLC is a purveyor of plywood and strip-planked kit boats, with an ever-expanding range of offerings. Harris was seeking a simply built, quick-to-rig daysailer to add to his product line. “It looks like a Banks dory,” Harris says— though the historical type was high-sided when lightly loaded, as it was meant to carry a great weight of fish. “I dialed out a lot of sheer because the Banks dory can be a bear in a cross wind.

“I had John Gardner’s book open in my lap when I designed it,” Harris says. “The rig came from the Beachcomber-Alpha.”

The Beachcomber-Alpha was a purely racing dory developed for the Massachusetts North Shore. Its rig is a leg-o’-mutton affair—a simple setup whose details and history Gardner describes in vivid detail over four pages of another of his books, Building Classic Small Craft. He traces the rig’s development from a primitive, unstayed pole carrying a main-sail and jib, to a relatively sophisticated affair with standing rigging, turnbuckles, and sail track. “The rig was no longer capable of being lifted out at the end of a day’s sailing to be carried home on the skipper’s shoulder; now the sails were furled and left on the boat. The boat was no longer rowed any more with the rig down, as was the lobsterman’s dory from whence it evolved.”

In the Northeaster Dory, Harris has retained the basic proportions of the Beachcomber-Alpha sail plan, and he’s kept the standing rigging and the sail track. But, rather than using turnbuckles, he attaches his shrouds to chainplates using simple snaphooks. These allow for quick rigging and downrigging. There is also a lug-rig option, which can be rowed with the rig stowed in the boat. While the marriage of dory hull and lug rig has no recorded historical precedent, it’s a practical hybrid that deserves careful consideration.

Chesapeake Light Craft

Chesapeake Light CraftThe Northeaster Dory is a kit boat, and so its strakes arrive in sections, for shipping purposes. These sections are joined by means of a puzzle joint, which ensures perfect alignment.

Building the Northeaster Dory

The Northeaster Dory is a kit boat, and it’s built in CLC’s patented LapStitch method. This technique yields a boat that appears to be of typical glued-lapstrake construction, but that goes together far more simply. It works like this: In lieu of the common changing bevels that occur along the plank edges of a conventional lapstrake boat, LapStitch uses what is, essentially, a long rabbet into which a neighboring plank nests and is wired to its neighbor—the stitching phase of stitch-and-glue. The joint does develop a gap, which would be unacceptable in a traditionally planked boat, but which is fine in one built of glued-together plywood, for that gap will be filled with thickened epoxy during the gluing stage of the operation.

Because of the limits of stock-plywood lengths, and the costs of over-the-road shipping, the plywood planks supplied in the kit do not arrive full length, and so their sections must be joined together by means of a precisely machined finger joint, which all but guarantees correct alignment. There are three thwarts, and each of these has glued to its bottom a piece of once-blue construction foam, tooled to its proper size and shape. I say “once blue,” because, in a nod to the boat’s aesthetics, CLC coats these pieces in epoxy and paints them black to mask their lumberyard origins. The resulting boat weighs 105 lbs, without the rig, and its maximum payload is 800 lbs—which is ample for two adults and their gear, or a crowd of four for a short sail.

Chesapeake Light Craft

Chesapeake Light CraftThe Northeaster Dory carries a leg-o’-mutton rig—a direct descendant of the Banks dory’s cousin, the Beachcomber-Alpha.

The boat has a removable rowing thwart and a sliding-seat option for more athletic rowing. It is steered by means of a push-pull tiller—a convenience in narrow-sterned boats whose hull forms don’t allow ample swinging room for a conventional tiller. It works like this: To a short crank fixed on the starboard rudderhead is attached the articulating long tiller. Push the tiller aft, and the boat steers to port; pull it forward, and you go to starboard. It takes a bit of getting used to, but becomes second nature within a short time. If one wished for less hardware and clutter, a continuous loop of line run through blocks could be substituted. This arrangement has gained recent notice with the popularity of the N.G. Herreshoff’s cat-yawl Coquina, which uses it to good effect.

With its relatively light weight and modest sail area, the Northeaster Dory accelerates admirably—even in the light airs in which I tested it. It has a slight tendency to pound when sailed bolt upright. But a dory isn’t meant to be sailed upright, and a 10-degree angle of heel introduces a chine to the waves, smoothing the ride noticeably. The handkerchief of a jib is integral to the boat’s performance, as it directs air over the low-aspect mainsail. “Take the jib down right now, and the boat goes dead,” said John Harris as we discussed the rig’s dynamics.

The boat we tested was fitted with a pair of Harken swivel-cam cleats for the jibsheets. These are convenient but optional; the standard kit, in addition to the precut hull panels, includes all mechanical fastenings, epoxy, fiberglass, and copper wire. There’s also one set of oarlocks included, though another could be added for a second rower. The basic kit costs $1,299. To get the boat sailing, one must purchase the optional sailing kit, including the mast and boom blanks, which must be shaped to their finished dimensions; Dacron mainsail and jib; rudder; daggerboard, and daggerboard trunk; shrouds; and hardware. The additional cost of the sailing kit is $1,099.

Chesapeake Light Craft

Chesapeake Light CraftBecause of the Northeaster Dory’s narrow stern, there’s no room to swing a conventional tiller. Therefore, steering is by means of a push-pull tiller.

Many years ago, the great simple-boat guru Phil Bolger designed an enchanting plywood dory called the Gloucester Light Dory. It’s roundly considered to be a study in perfection in plywood, as it combines grace, beauty, performance, and ease of construction in a single design. That performance, however, comes at a price: The Gloucester Light Dory predates the stitch-and-glue revolution, and so building it requires a materials- intensive construction jig that goes to the burn pile after construction. The boat was also meant for rowing only and, if I recall correctly, Bolger, who died last year, expressed safety concerns over queries regarding sailing rigs for this boat. John Harris is well familiar with the Gloucester Light Dory. In fact, he calls it a “nearly perfect boat.”

“If I was going to design a dory,” he said, “it had to be something completely different.” The Northeaster Dory is, indeed, a different breed of boat from the Gloucester Light Dory. It’s stiffer and carries more passengers, and it sails. It’s a bigger boat, and its method of construction is simpler as it requires no ladder frame or molds. The result is a thoroughly modern daysailer standing on the shoulders of the Gloucester Light Dory—and on the long and obscure dory tradition that came before.![]()

Chesapeake Light Craft, 1805 George Ave., Annapolis, MD 21401; 410–267–0137.

Chesapeake Light Craft

Chesapeake Light CraftThe Northeaster is flatter-sheered and sleeker than her Banks Dory forebears, but the lineage is unmistakable. Three rowing stations allow for solo and double rowing.

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.