Noank is a village in southeast Connecticut that looks out over Fishers Island Sound and the Mystic River. In the 19th century it was a major shipbuilding center, and about 700 wooden sailing ships came down the ways in shipyards in this picturesque little town. Noank is also the name given to an 18′ 2″ pulling boat designed by Nick Schade, whose small-boat shop is about a mile, as the gull flies, from the village. He is well known for his line of Guillemot kayaks, strip-built in wood, then ’glassed, varnished, and made show-room pretty.

photographs by the author

photographs by the authorThe seat support rail is designed for the Piantedosi sliding seat rowing rig. Under each deck is a sealed compartment for dry storage and flotation. The manual includes instructions for making the hatches from plywood.

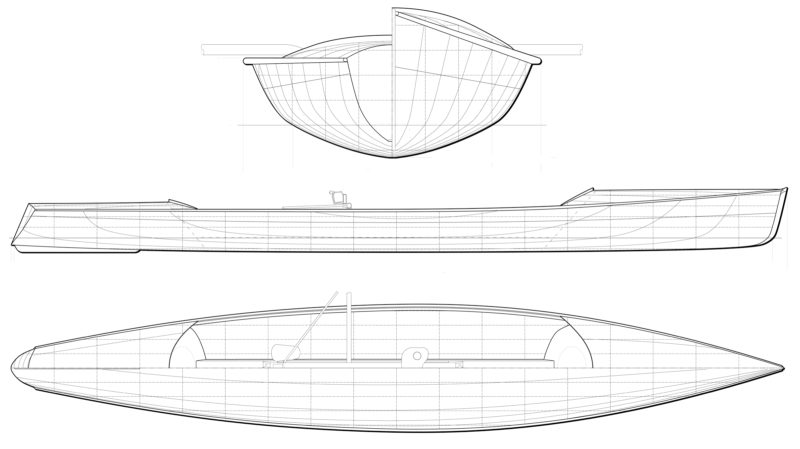

The Noank, also strip-built, is his first boat with a sliding seat. It is a half-decked recreational boat, beamy at 36″, with generous freeboard, and designed for exposed, choppy water. Schade also intends this to be a light and fast camp-cruiser, so the bow and stern have large, dry compartments for camping gear.

Like Schade’s other designs, this is a pretty boat, such is the judgment of five of us, all local rowers, who took it out for a spin. Tom Sanford, Janis Mink, Biddle Morris, Tom Tobin, and I are all members of Mystic River Rowing, and collectively, we have about 140 years of experience rowing in boats with sliding seats. All of us have seat-time in both recreational and racing boats, and most have taught sculling using boats similar to the Noank. Biddle has done hundreds of miles of distance rowing-camping and is our go-to guy on open-water rowing.

With the rowing rig occupying the space along the centerline, the rower has to get aboard with a foot planted slightly off to one side.

Beyond good looks, what does the Noank offer? How well will it handle in the afternoon southerly that’s common to Fishers Island Sound, the place the designer had in mind when he went to his drawing board? How is its calm-water performance? Does it track well? Turn easily? Is it slow or will it go? Is it fragile? Would it be hard to build? The short answer is that the Noank does well what it set out to do. It is fun to row, forgiving, and tougher than it looks.

The specifications call for planking of 3/16″ x 3/4″ cedar strips, shaped over forms cut from 1/2″ MDF or plywood and spaced at 12″ intervals on a strongback. The stripped hull is sheathed inside and out with 4-oz fiberglass cloth set in epoxy, and the ’glass is doubled on the bottom. Built to the designed specifications, this will be a strong, tough boat. The high crown of the decking helps stiffen the hull without adding much weight.

The Noank was designed with the Piantedosi rowing rig and conventional sculls in mind. For rowers new to sculling, the 6″ overlap of the oar handles will take some getting used to.

Schade notes that the Noank could be built without the decks and bulkheads if a lighter boat for protected water is the goal. The reverse transom keeps the waterline length almost the same as the overall length for speed’s sake. He says, “I really like the arched reverse transom, but it is a bit complicated. You could just have a flat vertical transom without changing the performance significantly.” A paper template, wrapped around the stern, indicates where it is to be cut to accommodate the curved transom panel. The stern is planked extra-long to make modifications possible.

The seat-support rail is designed to fit a Piantadosi rowing rig and adds significant strength to the hull. It is a wooden box beam 3-1/2″ x 4″ x 8′ 5″, with cutouts to reduce weight and provide drainage and ’glassed inside and out for rigidity. The anodized aluminum monorail of the rowing rig is held to the seat-support rail by two machine screws that are removable without tools. The rig weighs 22 lbs, and it can be put in the boat or taken out in less than a minute. It is designed to be rowed with racing sculls, which have a standard length of 284 to 290 cm (around 9′6″)

In a sprint, the Noank will do about 6 knots.

When completed, the Noank should come in around 53 lbs and all up, with rowing rig, weigh 75 lbs. For those of us who are not power lifters, loading a boat of this weight and girth onto a cartop carrier would be a two-person task. If it is to be beach-launched solo, a dolly or trailer is in order.

Getting in and out of wide rowing wherries can be awkward—for some it’s a long reach to get their weight planted over the centerline. The complication in getting onboard Noank is that you can’t put a foot on the centerline—the seat-support rail is in the way. Most of us just put a foot up against the box beam, held onto the oars, and accepted a quick heel angle as we shifted our weight onto the inboard leg. There is enough static stability in the Noank for this maneuver and for a rower to exit sideways, swinging both legs over the side to stand up in shallow water. The boat heeled sharply, but did not bury its rail. We tried the “Look Ma, no hands” routine while seated, letting go of the oar handles, and while this will result in a quick swim in most shells, the Noank only wobbled and did not flip. If you lashed the oar handles together in the middle of this boat—they overlap by 6″, the standard for sculling boats—the boat could look after itself while you eat lunch or take pictures.

The Noank would put beginning scullers on an easy learning curve. We would expect a novice to feel comfortable by the second or third lesson. That is largely because of the boat’s inherent dynamic stability: It wants to run on an even keel and if it is rocking side to side as it moves along, this is the rower’s fault for not sitting up straight and keeping the oar handles level. With its long skeg, Noank tracks straight, but is still easy to turn. In a moderate crosswind, a rower should have no problem dialing in a crab angle and maintaining a compass course.

Hobby-horsing can be a significant issue for most boats with sliding seats. The rower’s weight is two or three times the weight of the boat and rowing rig, and with that much mass moving back and forth, around 2’ with each stroke, the bow and stern want to bob up and down, killing speed. The goal is to keep the boat running level, and to that end this hull is designed with little rocker in the keel (only about 1”) and an almost uniformly rounded cross-sectional shape throughout the long cockpit of the boat. That provides needed buoyancy under the rower at both ends of the slide. Another speed killer, wetted surface, is kept in check by narrowing the beam at the waterline. The Noank has a beam of 36″ at the rail amidships; at the waterline it is 23”. The narrow waterline and arc cross section cuts down the area of skin subject to friction as it moves through the water. It also reduces lateral stability, but the flared sides above the waterline give the Noank an abundance of reserve stability when heeled.

Scullers like to talk about speed. None will admit that their own boat is a slowpoke, and many of us tend to boast a bit, claiming speeds too good to believe—“stretchers,” as Mark Twain called them. For the Noank, our numbers come from an impartial GPS during speed trials on a light-wind day with calm seas and no current. It takes a few pulls to get the boat going, but once up to speed the boat carries and glides well. This is a 4-5-6 boat: In the hands of an experienced sculler, rowing leisurely at a pace that can be held indefinitely, it will run at 4 knots. To reach 5 knots calls for rowing at a racing pace that’s sustainable over a 2,000-meter course. And 6 knots calls for a sprint, a “Power Ten” in crew parlance, and holding that speed for any distance would involve serious pain. The Noank moves as well as could be expected for a displacement hull with its 17.7′ waterline length. Once the Noank exceeds its theoretical maximum speed of 5.63 knots, even super-athletes are going struggle to make it move faster for very long. We found nothing to complain about in the Noank’s speed curve.

Building a Noank will call for time and patience, requirements for any high-quality, strip-built boat, whether the builder starts with plans or a kit. Both are available for the Noank. The finished product will require a reasonable amount of maintenance, but the construction is sturdy, and unless the boat is abused or neglected, it should outlive its builder. The five of us rowers agreed that the Noank is an all-round performer that rates well in its class. Tom Tobin even bought the plans and intends to build one.![]()

Carl Kaufmann trained to be a naval architect and marine engineer, but a career in journalism paid the bills for five decades. He has always had a second career: making things out of wood. Most of his time has been spent building boats from scratch, 10 in all. His current family fleet ranges from a 12-ton, 40’ yawl down to a 34-lb cedar shell. For variety’s sake, he made some mandolins and acoustic guitars. His home is on Block Island, off the coast of Rhode Island, but he spends a lot of time at his winter address in Mystic, Connecticut. He has a workshop in each place, so he is never at a loss for something to do in retirement.

Noank Particulars

[table]

Length/18′2″

Beam/36″

Draft/4″

Freeboard/8″

[/table]

Full-size Plans for the Noank are available from Guillemot Kayaks for $130. Kits are available for $1850 from Chesapeake Light Craft.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

A lovely boat. I have a similar setup in a wherry with options of sliding, single traditional, or tandem traditional.