One of the perks of my admittedly cushy job as a freelance writer is that I get to try out a lot of different boats—everything from small rowing dinghies to large sailing yachts. Inevitably, some are more appealing than others, and I have to admit François Vivier’s 15′ 3-1/2″ Minahouët wasn’t one I was particularly excited about sailing. It looked nice enough in the pictures, but my heart wasn’t exactly pounding to get out on it. All that was to change during a two-hour sail on a gusty day off St-Malo on the north coast of Brittany.

My acquaintance with the Minahouët started on the slipway at the Anse des Sablons marina near the historic old town. That’s where I met the boat’s builder Pierre-Yves de la Rivière, founder of the Grand-Largue boatyard at nearby St-Briac. The bespectacled Frenchman had brought PIANISSIMO, a Minahouët he had built for a client. The boat was rather understated, with a good deal of paint and the boat’s brightwork finished with oil stain rather than varnish. It all looked very workmanlike, if rather plain.

François Vivier

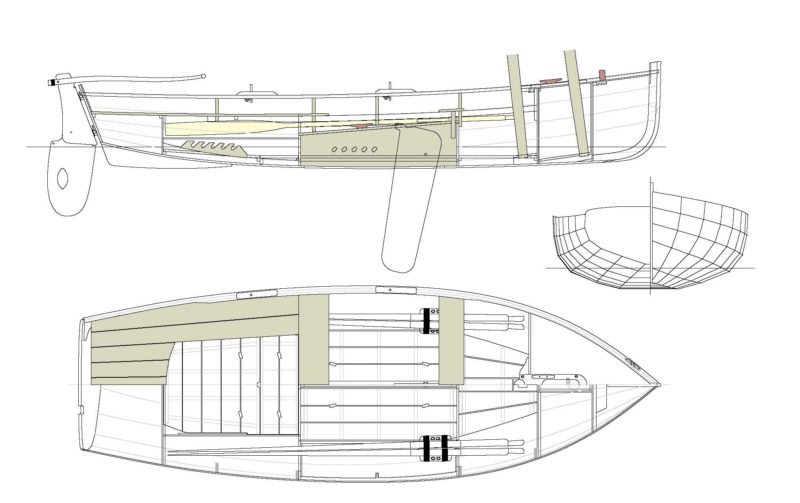

François VivierThe forward watertight compartment is accessed through two hatches because it is partially divided by a box for the forward mast partner and step. The aft mast partner—installed only for the sloop rig —is open; the mast will be lashed to eyelets yet to be installed.

Things got more interesting once Pierre-Yves had launched the boat and was setting it up to sail. The centerboard arrangement is ingenious. The board is fitted with a pin that slides down slots inside the case so that, once lowered, it can pivot like a conventional centerboard, and yet still be raised and removed like a daggerboard. You get the accessibility of a daggerboard with a centerboard’s convenience.

Nic Compton

Nic ComptonThe centerboard drops into the trunk like a daggerboard, but once it is in place it pivots on a short pin that’s embedded in the board.

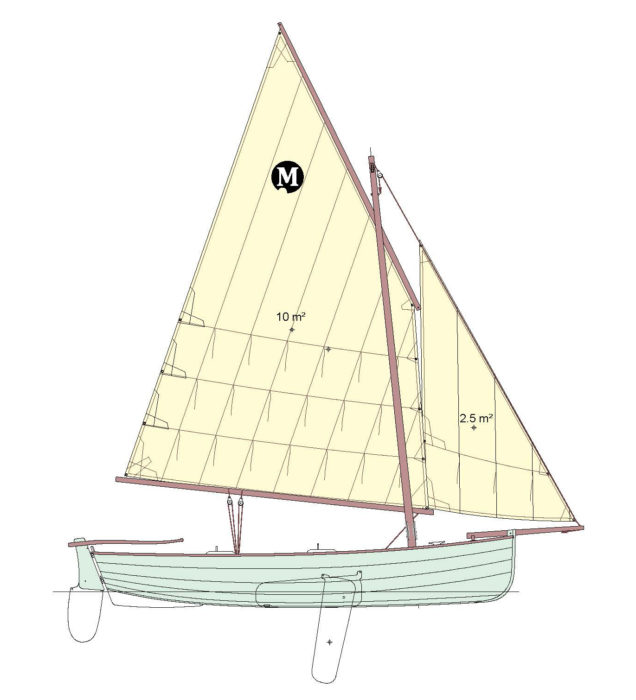

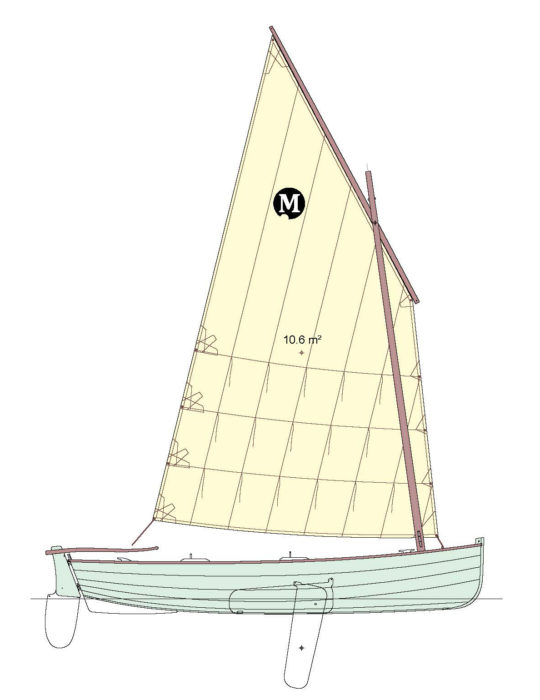

The Minahouët has two maststeps, so it can be rigged either as a sloop, with the mast set in the aft position, or cat-rigged, with the mast in the forward position. With two or more people in the boat, the sloop option is probably more efficient, while the cat arrangement is easier for singlehanded sailing. Either way, the boat is lug-rigged and there’s no need for stays, so rigging is simple and fast.

François Vivier

François VivierBoth rowing stations have removable and adjustable foot braces.

There are some interesting details. The bowsprit slips through a bronze hoop fastened to the port side of the stem head and is held in place in a chock on the foredeck, with a lashing to hold it in place. The tiller has a pin inside the slot that slips over the rudderhead. The pin engages a notch on the rudderhead, locking the tiller in place as it is pivoted into position. It may seem pretty basic stuff, but there is a purpose to the nearly fetishistic attention to detail: getting people on the water as quickly and easily as possible.

“The great advantage of the Minahouët is the ease of launching,” says Pierre-Yves. “You can do it on your own, so if it’s a nice day and you’ve got a couple of hours to spare, you can put the boat in the water on your own, and ‘baff,’ as we say in France, off you go, because it’s really very easy.”

Nic Compton

Nic ComptonVivier traces the development of the 15′ 3.5″ Minahouet to his 14′ 4″ Ilur and its predecessor, his 14′ 1″ Aber. All three have the option to rig with for a lugsail alone or as a lug sloop with the bowsprit and foresail.

Pierre-Yves and François had been collaborating for a number of years to develop new boats—mainly a 22′ dayboat and an 11′ 10″ pram—when they decided their next project should be a sail-and-oar boat. François had already designed several boats of this type, such as the Aber and the Ilur, and knew what the challenge was: “I tried to make a design that was as balanced as possible,” he says, “stable enough for family sailing, but also light and narrow enough to be enjoyable to row.”

To make the boat accessible to as many amateur builders as possible, the components were designed to be cut out by a CNC router. The approach marked a significant shift from the more traditional boatbuilding methods the pair had been using.

“It was first time we really explored potential of CNC cutting and of modern plywood construction,” says Pierre-Yves. “All the parts lock together. The longitudinal pieces lock into the transverse parts; you simply click them into place and everything falls into place naturally. When you build a boat manually, there’s always the risk of making mistakes when you line up the planks and the bulkheads can move. But with a computer design, there’s no possibility of error.” The plan seems to have worked and, since the Minahouët was launched in 2002, about 30 of the 40 boats launched were built by amateurs, mostly from kits, while the rest were built at the Grand-Largue boatyard.

Out on the bay off St-Malo, a brisk offshore wind was ruffling the surface of the sea, and ominous black clouds were piled up on the horizon. Alone aboard the Minahouët, Pierre-Yves shot across the bay, the very picture of insouciance. The wind continued to build, and after a couple of near-capsizes, Pierre-Yves lowered the mainsail and put a reef in. With the sail area reduced, the boat settled down and became more easily managed.

Nic Compton

Nic ComptonWith 135 sq ft of sail flying and the wind building, Pierre-Yves de la Rivière, the builder of this Minahouët, soon tucked a reef in.

After a little while, I traded places with Pierre-Yves and tried rowing the boat with the sails lowered. The owner he had built the Minahouët for had opted for single thole pins and grommets instead of rowlocks, which took a bit of getting used to. I’m not convinced there’s any real advantage to this setup, though it does look good and, providing you row against the grommet rather than the pin, the oars will rest alongside the boat if you let the handles go. More to my liking were the adjustable and removable footbraces fitted on either side of the centerboard case to give you something to push against while rowing.

Nic Compton

Nic ComptonThe side benches are below the thwarts and provide a shelf for storing the oars out of the way when they’re not in use. The centerboard trunk is also well below the thwart level to make it less of an obstruction when moving about the boat. The foot bracing for the forward station is split into two halves, one one each side of the trunk.

Once under way, I made good progress rowing against wind and tide and managed to row a fair distance back up the bay toward St-Malo. I’ve been spoiled by having my Western Skiff to row, which is considerably lighter than the Minahouët and therefore easier to row, but I had to admit that, in the windy conditions off St-Malo that day, the Minahouët carried its way better than my skiff would have. I could quite imagine rowing it several miles up an estuary or into harbor, although sailing probably is her best mode of propulsion.

Eventually, Pierre-Yves joined me on board and we shook the reef out of the main and raised the sails again. With the wind abating slightly, we eased onto a reach and sailed toward the off-lying islands of Le Petit Bé and Le Grand Bé. I felt immediately at ease with the boat, as if I’d been sailing it all my life. There was nothing unexpected, nothing to worry about; everything was where it should be.

Nic Compton

Nic ComptonThe unstayed mast of the sloop rig carries the 108-sq-ft main and 27-sq-ft foresail.

The Minahouët’s performance under sail was better than I expected. It was faster and pointed higher than I’d anticipated, and perhaps that was why I felt so relaxed on board. From the moment we set off, it performed impeccably and made me feel I was doing a good job; I didn’t need to squeeze that bit of extra speed, worry about the set of the sail, or try to point that little bit higher. The boat performed without being coaxed. It helped that we were going nowhere in particular and that it was a perfect autumn day and the coast was aglow with late afternoon sun. What was not to like?

I came ashore feeling rather pleased with myself. The boat had handled well, under both sail and oar, and I felt I’d got its number. It was only later I realized this feeling of satisfaction was what François and Pierre-Yves had aimed to achieve all along. It was thanks to their unassuming and deceptively simple design and its whole host of clever little details—an out-of-the-way place under the thwarts to stow the oars and a low centerboard trunk that’s easy to step over, among others, including many I probably didn’t even notice—that I was able to jump in the boat and sail it with such ease. My feeling of well-being was a direct result of their hard work.

There was one feature that looked like it might cause a minor problem while we were taking the boat out of the water. Unlike several other Vivier designs with well-rounded bows that lift themselves onto the trailer as they move forward, the Minahouët has a plumb stem, and may need to be lifted it to get it onto a normal trailer. The solution for PIANISSIMO was to ride a break-back trailer, which hinges in the middle until the roller is under the stem and then is straightened and locked into position before winching the boat the rest of the way up. Once on the trailer, there’s an elongated hole in the stem for a line to hold the boat in place.

Even though I had started out feeling decidedly skeptical about the Minahouët, at the end of two hours’ sailing I was completely converted to this deceptively simple little boat. Not only that, but I was pretty well convinced this was a boat a lot of people would find well worth owning. Park it in your drive, and the next sunny day, “baff, off you go!” Well, they do say it’s the quiet ones you have to watch.![]()

Nic Compton is a freelance writer and photographer who grew up sailing dinghies in Greece. He has written about boats and the sea for more than 20 years and has published 12 nautical books, including a biography of the designer Iain Oughtred, available at The WoodenBoat Store. He currently lives on the River Dart in Devon, U.K. He previously wrote about his adventures in his Western Skiff.

Minahouët Particulars

[table]

Length/15′ 3.5″

Beam/5′ 1.4″

Draft, board up/6.3″

Draft, board down/3′ 3.3″

Weight/551 lbs

Sail area/Loose-foot lug, 114 sq ft; Sloop, 135 sq ft

Maximum outboard power/4 hp

Kit construction time/450 hours

[/table]

Building plans for the Minahouët are available from François Vivier, Nautical Architect for 200 €.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Easier by an order of magnitude to drop the mast to row up wind. Just sayin’. Did they design a way to tuck the spars over the bow like the Norwegians do with their small double enders?

You are of course right, Ben. In my defense, the rowing bit happened by chance, while Pierre-Yves was messing about on another of his boats (more of which in the next issue of WoodenBoat). The spars all tucked away rather well on top of the thwarts, there being plenty of freeboard to raise the oars up high.

I have never seen that arraignment for a pivoting daggerboard before. I would love to know more about it and hear from others who have sailed with one.

It seems a great solution for those of us who have, on occasion run a bit on the “lean” side. 🙂 However, from the images, it appears to pivot into a centerboard trunk. If this is the case, why not just use a centerboard?

Thanks for another great article on a beautiful craft.

You’re right, it does pivot in the trunk. I think the main idea is that you can pull it right out and not worry about stones getting jammed between the case and the board when landing on a beach. The whole arrangement is much more accessible and therefor easier to fix than a conventional centerboard set-up. It would be good to hear from others who have had more experience of this system.

Rowing against the wind with the mainmast set is really arduous! When I have to row my 17′ Harrier, I lay the mainmast down and stow the mast-top on the quarter deck, where it gets locked in the corner underneath the stern breasthook. The lower part of the 19′ mast rests on a removable padded cradle on the left side of the bow and extends out about 2′ forward. I have to say that this arrangement is only good for rowing Venetian style in a standing position, using special forcole (Venetian oarlocks). I did not yet find a solution for rowing seated. Maybe I will have to use a shorter mast with a sprit-sail?

I can’t really see a way around that Detlef – unless you tried some outrigger rowlocks, in the style of Will Stirling’s expedition boats, or indeed most modern sports rowboats. The extra leverage gained might mean you can row with the oars farther out and leave space for the mast. Not ideal but maybe worth a try before you cut the mast down!

I think she’s a real beauty.

What interests me is the connection between tiller and rudder stock, have observed the ease in which they can be separated and tiller then stored. There also appears to be some kind of block on the tiller in some pictures? Can anyone help in these matters?

I’ve read this article at least three times now. Great writing, Nic, and what a beautiful and functional boat. My current boat has a lot of little details that make trailering and sailing quick and easy, and I think too many designers overlook these things. In the long run these little details provide a lot of satisfaction.