My life totally changed in my mid-20s when a casual invitation to a wedding in India unexpectedly became six months of travel through South Asia. Upon my return to the USA, I realized I was addicted and decided to travel the world full-time. The next target of my travels became Africa, where I planned to cross the continent from Cape Town, South Africa, to Cairo, Egypt. I was a year into that journey, having just ridden a single-speed bicycle across Botswana and the Kalahari Desert, poring over maps of the continent and planning my route north, when I came across what would become my next challenge: Lake Tanganyika.

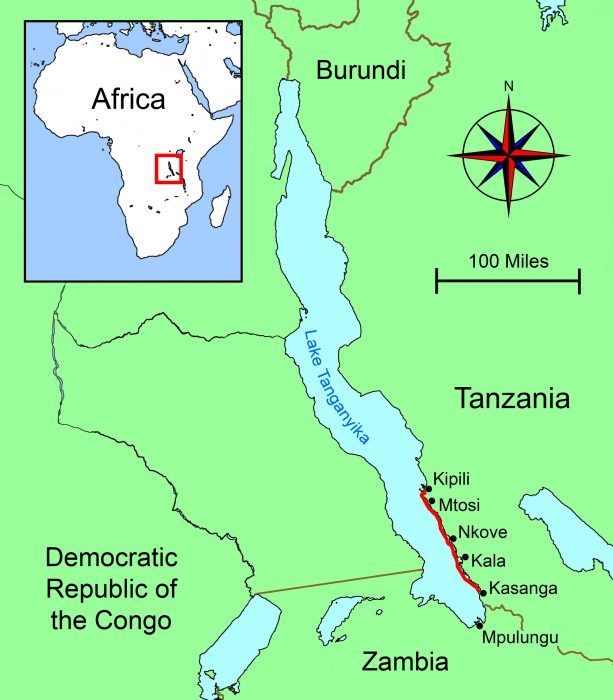

Sandwiched between the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west and Tanzania to the east, the lake is 418 miles long and up to 4,820 feet deep. It is not only the longest and largest of the African Rift Valley lakes, it is the longest, second largest by volume, and second deepest body of fresh water on the planet. As I learned more about this natural wonder, I couldn’t get it out of my head and began dreaming up ideas of how to explore it for myself. The plan I came up with was to paddle the length of the lake, south to north, solo, in a locally built wooden boat.

.

The southern tip of the lake lies in Zambia, where I’d been for the past three months, and from the lakeside town of Mpulungu I took the MV LIEMBA, a former German World War I vessel built in 1913, north into Tanzania, where I began my search for the boat I would paddle up the lake. In this part of the world, all life and commerce revolves around fishing, so boats are a way of life. Although there are a handful of steel or fiberglass boats on the water, they are limited to the cargo ships that travel the lake and a few foreign fishing vessels.

I would guess that 99 percent of the boats are made of wood by local craftsmen on the shore, using only hand tools with not a measuring tape in sight. I saw a range of wooden boats between roughly 12′ to 35′ long, all using the same general design and construction techniques: 1″- to 3″-thick planks laid out parallel and end-to-end, fastened with common nails or staples, a few haphazard ribs and thwarts, and cotton or scraps of cloth for caulking. In Africa, “watertight” is a relative term, and I never once saw a boat that didn’t leak a good amount of water and require nearly constant bailing.

I disembarked LIEMBA at a small tourist lodge near the village of Kasanga, situated 18 miles from Mpulungu on the Tanzanian shore. The lodge became my base camp to outfit myself for the journey ahead. While I would have liked to begin the journey at the true end of the lake, my Zambian visa had expired. I’d also been told by locals I would have better luck finding a boat on the Tanzanian side of the border. I had been spending much of my time staying in the bush earlier on the trip, so I already had all the necessary camping gear, and after a few long bus trips to towns in the surrounding area I had gathered about two weeks’ worth of dry food, coils of rope, 3 gallons of unleaded gas for my camp stove, and everything else I could think of.

The owner of the lodge obviously had grand visions for the place, but it was miles from any paved road and had nothing you could even call semi-modern infrastructure; I only saw a handful of local guests during my weeklong stay. It didn’t have a bright future, but the owner was friendly and acted as a middleman to help procure a boat from a local fisherman, even though he obviously didn’t understand what I was trying to do or why.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorDespite seeing boats everywhere, it took surprisingly long to buy one. This photograph of the author’s boat is from the first time he ever saw it at the lodge run by the man who found it for him. The lodge owner then had three men work to repair the boat prior to his setting off.

The boat looked pretty bad when I first saw it. There were surprisingly large gaps between the planks, big enough to fit a pencil through. The ribs and thwarts had been rounded smooth by many years of use, and the miscellaneous pieces, some bare wood, others showing traces of different colors of paint, showed how the boat had been cobbled together from various other boats during its hard life.

The head builder, wearing white, hammered a nail into the hole he had drilled. The board was then laid along the one below and another nail was added on the other end. No other fastenings were added.

I watched over the next two days while it was repaired by three local boatbuilders with handsaws, an eggbeater drill, and new cotton caulking. I felt satisfied with its condition. It still wasn’t great, but that’s part of the adventure, right? Besides, I didn’t know anything about this kind of boat, it was the only boat available to me, and because I traded my bike as part of the deal, I only spent $19 cash for it. This was the first boat I’d ever owned.

The day I loaded up my new boat and set off for the very first time I felt confident, even though I had no idea what the hell I was getting myself into. There was no guidebook for this kind of thing. I had no idea how long it could take, no ability to contact the outside world if things went wrong, and had done no real testing of my boat. I didn’t even have a chart, just printed photos I’d taken from a country-scale map. I had been told that I was going to be traveling between dangerous and unforgiving shores on the west side of the lake and the truly remote African bush to the east.

Minutes before setting off the author posed with his unnamed craft outside of Kasanga, Tanzania. He had three paddles, all different, that he’d use as oars. He was ready to begin the adventure.

Boats such as mine are usually paddled like canoes with two to four people, and often sailed with sails that were usually made of rice sacks sewn together. Paddling solo would be awkward, so I had to take a different approach. I made holes in the gunwales with my Leatherman tool, then looped and tied rope through them, making primitive oarlocks so I could row the thing. With calm water as far as I could see and clear skies, I happily pushed off into the unknown.

The first two hours of my journey went well enough, and I made slow but steady progress north. Then the wind picked up, and with it came the waves, and suddenly I was struggling to make any forward progress. I scanned the shore, and there was no place to land—it was all too rocky or dense with brush. A beam sea crashed against the boat, dumping water in and knocking loose the cotton that sealed the hull. An unstoppable cartoon-like fountain of water sprang up from the bottom, and suddenly I was in panic mode, worrying about capsizing and sinking. I feared this might, at best, end my trip up the lake and at worst that I might be injured, or lose critical gear and not be able to finish my trip across Africa.

My only option was to keep fighting. I saw a few mud huts indicating a village a few hundred yards ahead and paddled as if my life depended on it. I nearly capsized as I finally came to shore, and a group of locals rushed down to help this crazy white guy who had just made quite an entrance into their settlement. After we dragged the boat ashore, the villagers carried my bags for me and brought me to the headman (who spoke no English), paraded me around the village, and fed me dinner. The whole time, a group of 15 children stared at me. At the end of the evening, I was taken back to the headman’s mud-and-grass home where I slept on the dirt floor. It had been an interesting first day.

As he left the village that had taken the author in on his first night, the chief, wearing the black shirt, and a group of young boys stood on a pile of nets and ropes to watch him leave. He was used to getting strange looks from locals and this day was no exception.

Luckily for me, the next few days on the lake were less chaotic and I began to get the hang of what I was doing. Each morning I would wake up early, eat a cold breakfast, pack up camp, and hit the water. As I rowed north, I quickly learned that I was rarely alone. Even though I was seldom close to other people or boats, I could almost always look in the distance and see fishermen on the water somewhere. They were often sailing farther out than I was, in search of fish in the deeper water near the middle of the lake.

The sun-faded clothes that had already taken him halfway across Africa served well for rowing. The bicycling gloves he happened to have were a life-saver for his hands. The improvised plastic rope oar locks needed to be replaced every day or two.

Most places that had enough sandy beach to pull up boats and any sort of flat space on the land would at least have a few grass-roofed mud huts. This made finding private campsites a real challenge, and I found myself the accidental center of unwanted attention more than a few times.

Along the shore there were small settlements, villages, and a few places that could be called towns. Even those had neither paved roads nor electricity. Some of the people I met in these places were able to make a modest living by pulling out enough fish to dry in the sun on drying racks made of sticks and reeds. They’d bag them up and sell them to passing traders. Many others, often refugees from the Congolese War on the other side of the lake, struggled as subsistence fishermen.

Even when things were going well, safety was always on my mind. I’d been warned about hippos and crocodiles, and a kid was actually killed by a croc just outside where I was staying one day. I was so concerned about my boat, the difficult shoreline, and the afternoon wind and waves that I didn’t have the energy to worry about crocs and hippos.

After observing how the locals repair their boats, the author followed suit and came up with a method: a rock and a table knife to tap the cotton back into the massive gaps in his boat. While some of the joints were tight, most were not and leaks were a constant problem.

My boat was terrible. Even under the best of conditions there were always two or three inches of water in the bottom, keeping my feet soaked. As a matter of routine I bailed every couple of minutes, but sometimes the boat would spring a leak that required my immediate attention to keep from sinking. I’d bought a large ball of cotton to do my own repairs along the way. I had a table knife and rock to pound it into the cracks, which I did frequently.

The other big problem I had with the boat was its immense weight. I could never pull it up the beach and totally out of the water. Overnight, the waves would beat on it, sometimes creating leaks that required hours of work to repair each morning. The shoreline was problematic because it was so rugged there were often long stretches, sometimes a kilometer at a time, with no opportunities to land a boat. Either it was a cliff, or it was lined with boulders, or the bush was so thick all the way to the water’s edge it was impenetrable.

Cliffs like these were just some of the stunning elements of this wild landscape. The author stopped briefly here to admire the cliff swallows that had built nests on the rocks, but didn’t linger. If the wind and waves that arrived daily came early, it would be impossible to get off the water in a place like this.

I quickly learned just how dangerous this was as I became accustomed to the winds that arrived every afternoon. I noticed the fishermen usually headed to land in the afternoons as well. Maybe two or three strong men could paddle one of these boats in rough conditions, but there was simply no way I could make any real progress rowing solo once the winds began. I was constantly looking for places to get safely to shore. Landings were scarce, and I sometimes had to backtrack to stop for lunch or make camp. If I found myself in one of those long stretches with no pullouts when the winds picked up, I knew my boat would simply be blown to shore with me in it and I’d have to watch it be slowly smashed to pieces on the rocks.

Although some fishermen on the lake used nets, most used improvised hand lines. Scraps of metal were often used to sink a line with multiple hooks to the depths where the fish were.

Some days I would come across people fishing or traveling by boat to another town who spoke a little English, and we would exchange a few sentences before running out of things to say. Most of the time I would simply shout “Jambo!”—hello in Swahili—while rowing and bailing out my boat, hour after hour.

The going was always slow, and to be honest I never really knew where I was. My map showed major towns, but when I’d ask locals about the names of places, it seemed I rarely got the same answer twice. The people were always very friendly; smiling, waving, and often even giving me fish as a gift. This was certainly not a place that sees foreigners, much less ones using a boat like theirs. I was clearly an oddity, but I always felt respected and was absolutely certain I could count on the locals to help me if I needed anything.

From a distance he could hear a large group of people cheering, so naturally he went to have a look. What the author found was a group of men, boats circled up, working together to pull up a large net full of fish. All the young boys of the village were there to watch and play, and everyone was very excited to see a strange white man show up.

During the first few days, I hadn’t gotten far and my boat was a constant problem, but I felt about as comfortable as possible for being a strange white man rowing my way along a wild African shore. So long as I was on the lake, I decided I’d better start eating the local fish, and one afternoon bought a bunch from a local man who spoke no English, as we both bobbed about, far from land. That afternoon I found a little cove with clear blue water, a sandy beach, truck-sized boulders on each side, and monkeys chattering in trees.

The author’s campsites were often stunning spots. Almost every night he found himself alone on sandy beaches, between boulders and lush greenery and looking over the lake toward the Congo on the other side. Here you can also see his jug of tablet-purified water, gas for his stove, and his PFD and drybag, which he kept inside another sack to protect it from sun and abrasion.

It looked like something from a fantasy movie, and I was in high spirits. I cooked the fish for dinner that night, and shortly after lying down to bed realized I was about to suffer a serious round of food poisoning. Alternating between mattress-soaking sweats and waves of cold that seemed to defy all logic, it felt like my intestines were full of razor blades. I had one of the worst nights of my life and spent the next two days and nights lying in the bush in such intense pain I couldn’t eat or sleep. I was hardly able to move or even keep my eyes open. Four nights passed before I was able to leave that spot.

I recovered eventually and, oars in hand, returned to the lake to keep going. Feeling surprisingly normal again, I propelled my heavy, graceless boat through the water. It continued to leak, and keeping the thing afloat was a full-time chore. I was only eight days and maybe 75 km up the lake, but I was fed up with the boat, and questioned my journey and its chances of success, but still I rowed on, hour after hour, day after day. I found a large, unoccupied beach, made camp, and tried to get some sleep. But this proved a challenge, because the wind and rains picked up and I spent all night listening to the waves pound my boat, expecting it to be destroyed or float away in the night. The boat stayed put, and come morning it took four-and-a-half hours of repairwork to get back on the water.

He stopped for food at the main harbor outside of Wampembe. In the two weeks he spent on the lake, not once did the author see a dock. All boats are simply dragged onto the sand in common areas, and a line tied to the shore keeps them roughly in place.

It wasn’t long before I came to the town of Wampembe, and I paddled onto the reddish sandy beach, crowded with dozens of large fishing boats. The usual throngs of people came to stare at me as I tied up my boat and walked the dirt path to town. It was the largest village I’d been to since leaving Zambia, meaning there were a few concrete buildings with metal roofs, a truck or two, and some small shops.

I managed to find a cold Fanta soda, which at the time, was something truly wonderful. I bought some fruit, vegetables, and cookies from a woman sitting on the side of the road. It was the first time I’d gotten fresh food since setting off 10 days earlier, and it really did lift my spirits.

Sails on the local boats were simple: three flexible wood poles, a few ropes, and sewn-together rice sacks. The boat the author had was also set up to sail as this one is doing, but he did not want to add that complication to the trip and did not buy the rig when it was offered. He had doubts that such a setup could actually be sailed upwind.

That same day, I arrived in another town to spend the night, where I was taken in by the teacher of the local school. He was a huge man, with hands that made me feel almost like a child when we shook hands and a warm, inviting smile. He spoke English very well, and we sat down to dinner of beans and ugali, a cornmeal dish that is the staple food of the region. We ate with our hands and talked about village life. I woke up after a good night’s sleep, the first in a while, and watched his students outside, picking up sticks and leaves to clean the school yard and then exercising together. With their morning routine over, they carried my bags to the beach to send me off.

The people of the lake had once again welcomed me with open arms and brightened my day, but as I hit the water and my boat began filling with water at a rapid pace, my frustration with it grew stronger. I rowed and bailed for a few miles, but then I heard the sound of hammers in the distance and knew it was a boatyard of sorts. I could get some more lasting repairs than I had been able to make.

Local boat builders re-caulked the boat in a tiny town of unknown name. The yellow caulking here is the oil-soaked cotton, something the author paid extra for, and that was supposed to do a better job of keeping water out.

“Boatyard” is perhaps too grand a term for what I found when I came ashore. It was just a sandy beach between a few boulders, lined with wooden boats and mud huts—but there men were working on boats, and it was just what I needed. I found a helpful man named Daniel, and in no time at all he had a team of men replacing a plank and recaulking the entire boat.

Daniel and I drank tea and ate fried dough as we talked; he told me about fishing, marriage, growing up as a refugee fleeing violence in Burundi, and much more.

The repairs didn’t take long, and after I’d had experienced boatbuilders working on my boat, I was once again optimistic, but that optimism faded quickly. Despite all the work done, it leaked just as much as before. That was when my spirit just kind of broke. I still had a few gallons of gas for my cook stove, and the thought crossed my mind that I ought to just torch the thing and walk away. However, as much as I was beginning to despise the boat, I didn’t want to destroy it, when people here had so little. Destroying something as valuable as a boat, even a leaky one, would be the height of arrogance. I decided to sell it at the next possible opportunity and give up on my boating journey.

Every few minutes the author attended to the ritual of bailing out his leaky boat. Here you can also see the coil of cheap rope that he used to improvise short-lived oar locks. He used the rest to tie the boat to shore when he was unable to get it out of the water for the night.

Giving up was not something I took lightly, and although it was easy to place the blame on my boat, and probably rightfully so, it was still an extremely tough decision to make. I felt like a failure, which made me a little angry. I still had three tough days of rowing ahead of me before I reached Kipili, an old mission station that I decided would be my new end point, and there was no time to relax. The scenery was still otherworldly, with brightly colored lizards, house-sized boulders along the shore, and rainbows that appeared during brief rain showers. I did my best to still take it all in, but my heart wasn’t in it.

Those last days of the trip dragged on, and on my last full day, the afternoon headwinds and waves caught me out on the lake. I was trying to find a pullout when an especially large leak formed, and my boat was soon one-quarter full of water. Just 100 yards from land, I was rowing with all my strength but wouldn’t make it to the nearest land, and would be blown instead into a large bay to the south where my boat would surely sink. My situation got even worse when one of my rope oarlocks broke and I was suddenly reduced to using a single oar, hanging over the bow and paddling the heavy boat as if it were a canoe. In a panic I considered jumping overboard and swimming the boat to shore by the bowline. By some miracle I made it to shore, then collapsed in exhaustion.

Eventually I did make it to Kipili, 14 days and roughly 95 miles after setting out, 310 miles short of my original goal. I can’t say I felt any sort of accomplishment in those final moments of the trip, but knowing I’d never have to spend another minute rowing that boat gave me tremendous relief.

My continuing journey across Africa went on for many more months by foot, using local buses, a train, and eventually another wooden boat on the Nile (which I hired along with a guide this time), and through many more countries before I reached Egypt and dipped my feet in the Mediterranean Sea, but nothing I did before Lake Tanganyika, nor after on the trip, was comparable. The remoteness and isolation from the outside world, the unforgiving environment, my interactions with the people, the constant danger and the time alone on the water, with nothing but my thoughts, was an experience I will treasure for the rest of my life.

I think if I’d set out with a boat that didn’t require daily repairs, rowing the entire length of the lake would have been possible, and knowing that still bothers me a bit. I have occasionally fantasized about returning to Tanganyika to finish what I started, but I know that will never happen. All I can do now is look back at what I saw, what I did accomplish, and what I learned along the way. When I do that, I can recall even the bad times with a smile on my face, and when I retell the stories with friends and family, all I can do is laugh.![]()

Scott Brooks grew up in Seattle, Washington, with outdoor activities in the mountains being his family’s primary recreation. Hiking and skiing were their main sports but multi-day canoe and kayak trips were not uncommon. Scott also did a bit of sailing in high school. He and his wife live in Washington’s San Juan Islands, where he climbs and cuts trees for a living. His home and job are on different islands, so he uses a 12′ aluminum boat (that he got for free) with a 9.9 outboard to commute, rain or shine. It could hardly be more different from his time on Tanganyika, but he still loves being on the water.

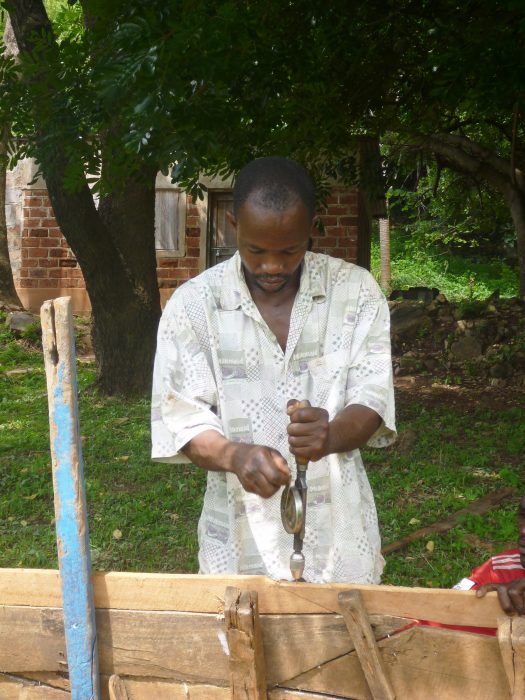

Boatbuilding in Kasanga, Tanzania

I never once saw any sort of power tool, these and a few other hand tools were all that the locals used to repair my boat before I set out. I especially like the hammer head welded onto a piece of pipe for a handle.

Rip-sawing has a different look in this part of the world. Having two hands on the handle makes good sense, even if the grip is unconventional.

This is a very simple type of adze that I saw in many parts of Africa and used for countless purposes. Here the man is using it to trim down a board in order to make a tight fit in the boat.

This egg-beater drill was probably the most high-tech tool I saw anywhere. In the construction process, metal fasteners were used very sparingly, but to keep this unlikely union of plank pieces together, a hole for a nail was drilled.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small wooden boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

I am absolutely exhausted just from reading this story! I will never again complain about those very infrequent occasions when I have to bail insignificant (compared to what Scott suffered) amounts of water from my Adirondack guide boat.

Wonderful story. Stories of inexperienced and underprepared adventures done on the smell of an oily rag are always much more interesting and remind me of my own foolish adventuress leading to shipwreck on a remote island in New Guinea. How interesting it was to read the still-primitive nature of boatbuilding in Africa. I spent many years in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands and their canoes were of much better quality that those described in the article

Terrific adventure! When was this trip undertaken? What would the conditions there be like now?

I agree with Steve as I too am exhausted from reading the story. Sometimes we lose sight at what we really have and take it for granted.

A well done trip. Thumbs up!

Not to be a Debbie Downer, but what happens when he turns 66. He needs to put all those skills into a bag and move to Maine and run a boatyard.

Great to read your story. I was doing some research for a friend who is with a bicycle from Windhoek to Nairobi. I found him while I was traveling with a Toyota Hillux. You were with a boat. Whatever you do, the important thing is to do something with your life : to live and to learn. You didn’t reach your destination as planned but this wasn’t in no way a failure. All experiences help us forward in a way that we sometimes only understand much later. I also like your writing style by the way.