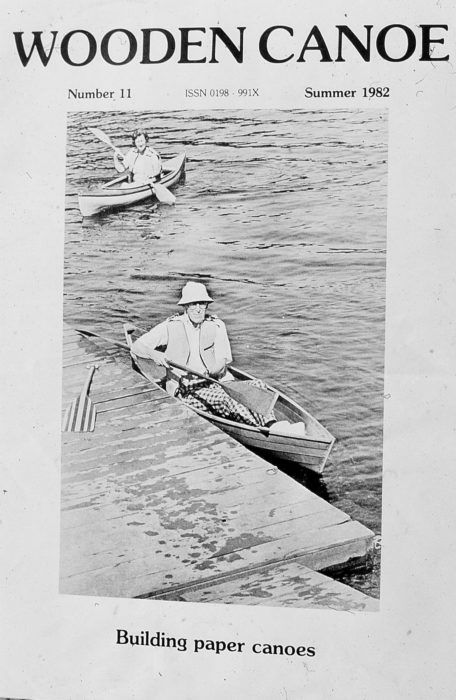

Nathaniel Holmes Bishop III was born in Medford, Massachusetts, on March 23, 1827, and died in Glens Falls New York, July 2, 1902. In his time, he was quite well known for books he had written about his travels in small boats. I first heard about him, quite by accident, in the spring of 1982. I was working part-time at the Wooden Boat Shop, located, appropriately, on Boat Street in Seattle. On a sunny summer morning, I was manning the front counter when the mail came in and among that day’s mail was the latest issue of Wooden Canoe, Volume 11 of the Wooden Canoe Heritage Association’s magazine. The store was empty so I had some free time to browse through it.

This issue of Wooden Canoe introduced Nathaniel Holmes Bishop to me. Eight years later my son would be named Nathan in his honor.

I skimmed over an article written by Walter Fullam of Princeton, New Jersey about building canoes by laminating kraft paper with glue. That was mildly interesting, but what captivated me was an excerpt from Bishop’s Voyage of the Paper Canoe: A geographical journey of 2500 miles from Quebec to the Gulf of Mexico, during the years 1874—5. Hungry for the rest of Bishop’s story, I found an old copy in the University of Washington’s library and read it from cover to cover. His writing was certainly a product of the 19th century, but charming and evocative:

Finding that the wind usually rose and fell with the sun, we now made it a rule to anchor our boat during most of the day and pull against the current at night. The moon and the bright auroral lights made this task an agreeable one. Then, too, we had Coggia’s comet speeding through the northern heavens…. In this high latitude day dawned before three o’clock, and the twilight lingered so long that we could read the fine print of a newspaper without effort at a quarter to nine o’clock P. M.

And he did not lack a good sense of humor. About his parting with David Bodfish, his traveling companion, briefly, from Quebec City to Troy, New York, he writes:

I had unfortunately contributed to Mr. Bodfish’s thirst for the marvellous by reading to him at night, in our lonely camp, Jules Verne’s imaginative Journey to the Centre of the Earth. David was in ecstasies over this wonderful contribution to fiction. He preferred fiction to truth at any time. Once, while reading to him a chapter of the above work, his credulity was so challenged that he became excited, and broke forth with, “Say, boss, how do these big book-men larn to lie so well? does it come nat’ral to them, or is it got by edication?

Having grown up on the West Coast, I knew about the Inside Passage woven into the coasts of British Columbia and Alaska, but I had no idea that there was an even longer and better protected thread of waterways that connected Canada to Florida. After I returned Voyage of the Paper Canoe to the library, I paid regular visits to the book with a weighty pocketful of nickels and carefully photocopied every page of it. I needed to have a copy because I’d decided, even before I’d finished reading the book, that I would build a paper canoe and retrace Bishop’s route. He would be my guide. I was approaching 30, not quite sure what I was going to do with my life, and had no obligations to prevent me from embarking on a voyage that would take several months. I spent the next year trying to figure out how to laminate a paper hull, and in the late fall of 1983, with a craft-paper canoe of questionable durability on my Volkswagen bug’s roof racks, I headed to Quebec City. Four months later I had reached Cedar Key on Florida’s Gulf Coast. The voyage had only whetted my appetite.

I came home, read Bishop’s Four Months in a Sneak Box: A boat voyage of 2600 miles down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, and along the Gulf of Mexico, made a photocopy of it, and in the winter of 1984 built a sneak box. In November of 1985, I loaded it on top of a drive-away and headed across the country to Pittsburgh, where I’d follow Bishop again to Cedar Key, this time by the inland route.

I kept my copy of Four Months in the chart case and kept up with Bishop day by day as I descended the Ohio River and then the Mississippi with him. Not all of the landscape had been changed by the 110 years between us. Cave-in-Rock, a 30′ wide cavern on the Illinois side of the Ohio is still there, as is the burial mound in Moundsville, West Virginia. And most of the Mississippi is isolated from civilization by levees so it’s the same wilderness the Bishop rowed through and the people who live along the river were every bit as interesting and generous as they had been in Bishop’s account.

I made good time, especially along the Gulf Coast where I had some good sailing, and reached Cedar Key in 2-1/2 months. Although my pursuit of Bishop was suddenly over, he had given my life a new and clear trajectory, one that eventually lead me here, to Small Boats Monthly.

Of the last night of his voyage, Bishop writes:

Lying there under the tender sky, lighted with myriads of glittering stars, a soft gleam of light stretched like a golden band along the water…. It seemed to be the path I had taken, the course of my faithful boat. All I could see was the band of shining light, the bright end of the voyage.

What he had seen behind him, that bright path, was what I had seen stretching out ahead of me.![]()

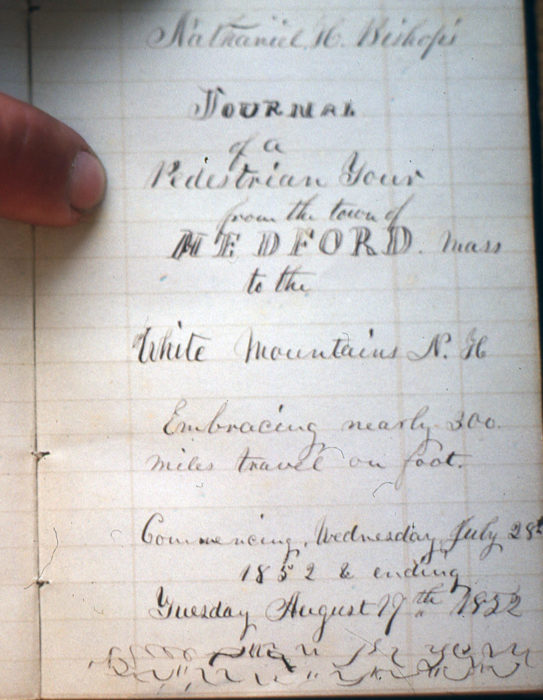

Bishop was traveling and writing long before his well-known voyages. This journal, dated 1852 and written when he was 15, is titled “Nathaniel Bishop’s Journal of a Pedestrian Tour from the Town of Medford, Mass, to the White Mountains, N.H., Embracing nearly 300 Miles Travel on Foot.” He also kept a journal later in his life called “Log of the Lorna,” an account of travels by boat with his wife, Mary Ball. I saw this journal, and other Bishop memorabilia, in the archives of the Ocean County Library, in Toms River, New Jersey.

The two routes, paper canoe on the right and sneak box on the left, both end at the Cedar Keys on the Gulf Coast of Florida. Together they add up to more than 5,000 miles.

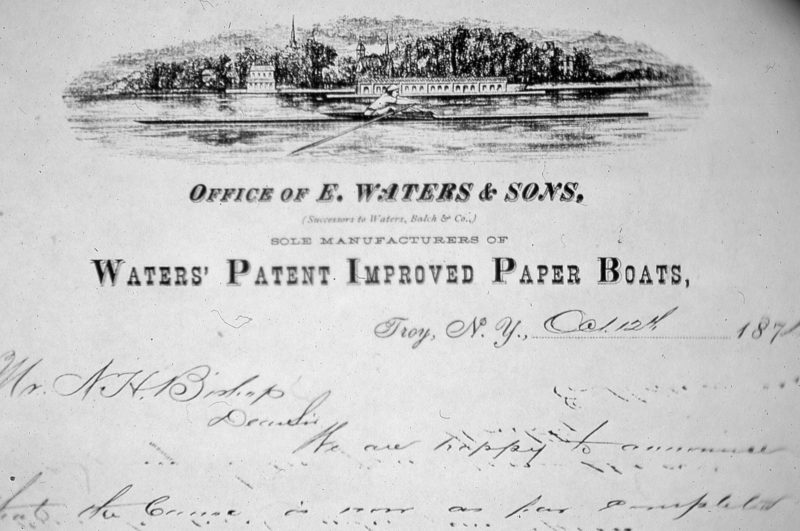

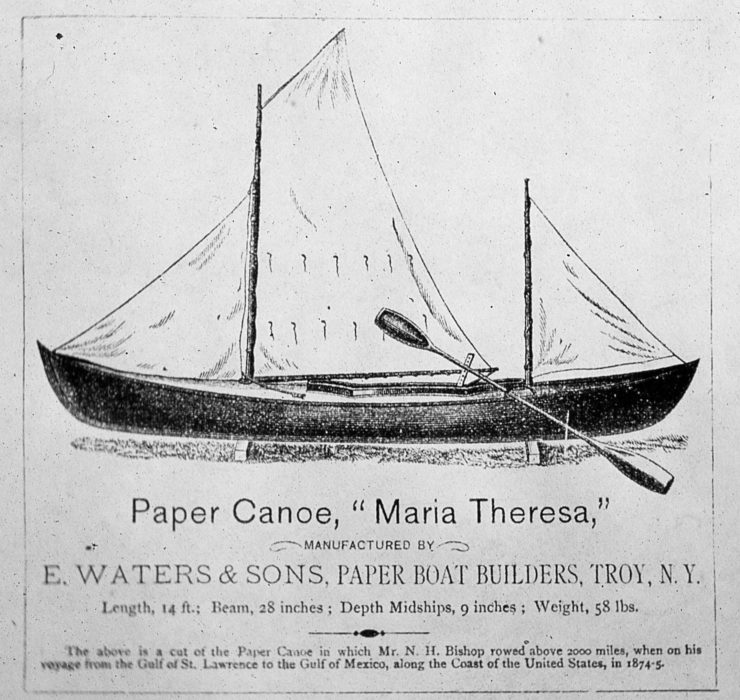

Bishop travelled from Quebec City to Troy, NY, in a lapstrake double-ender, MAYETA, an 18′ lapstrake canoe, which proved too heavy and unwieldy. Bishop had heard about the tough, lightweight boats being made of paper by Waters & Sons, the only company making paper boats, as well as observatory domes and racing shells. The company was in Troy, so he ordered a paper canoe. This letter, dated October 12, 1874, seems to be an announcement of the completion of the canoe. Nine days later, having christened the 58-lb canoe MARIA THERESA, Bishop resumed his trip southward on the Hudson River. George Waters, paddling his own paper canoe, accompanied him for a few miles.

Bishop’s paper canoe became a selling point for the Waters company. His books were quite popular and often given out a prizes to school children.

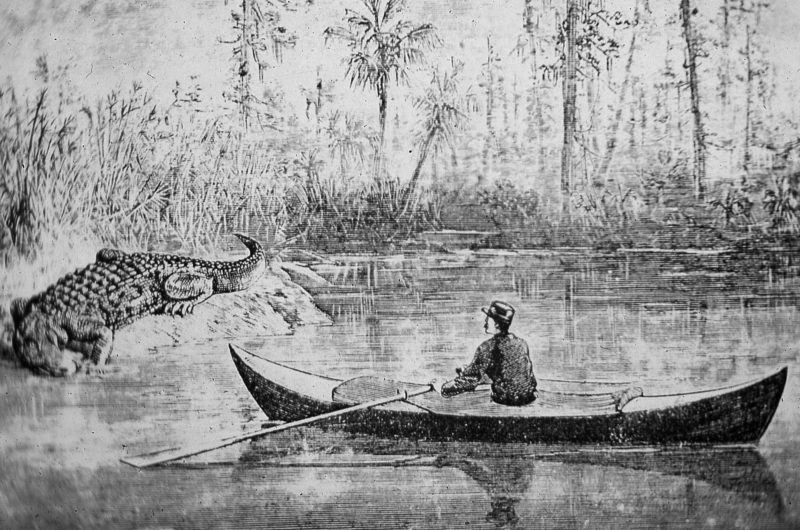

Bishop rowed MARIA THERESA through southern waters in February of 1875, and the cool weather would have kept the insects at bay and made the alligators sluggish.

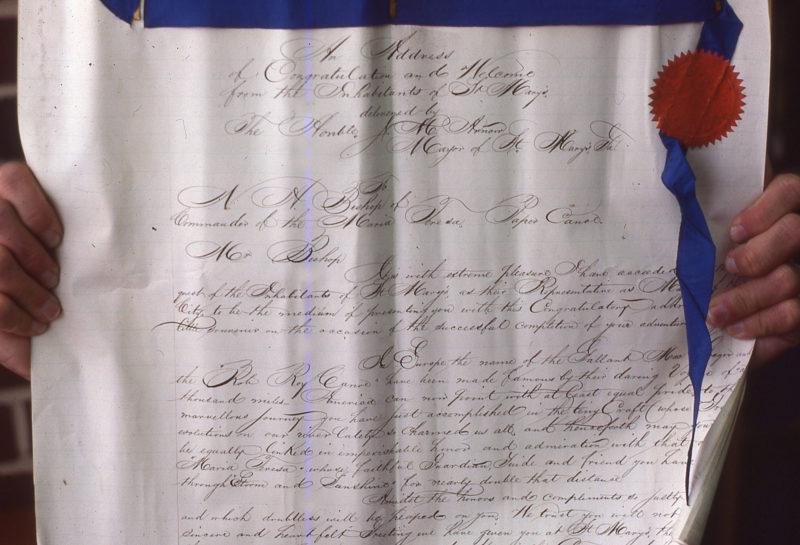

News of the Voyage of the Paper Canoe raced down the East Coast ahead of Bishop. The town of St. Marys, Georgia, awaited him with this elaborate document, “An Address of Congratulation and Welcome from the Inhabitants of St. Mary’s” that was presented by the city’s mayor.

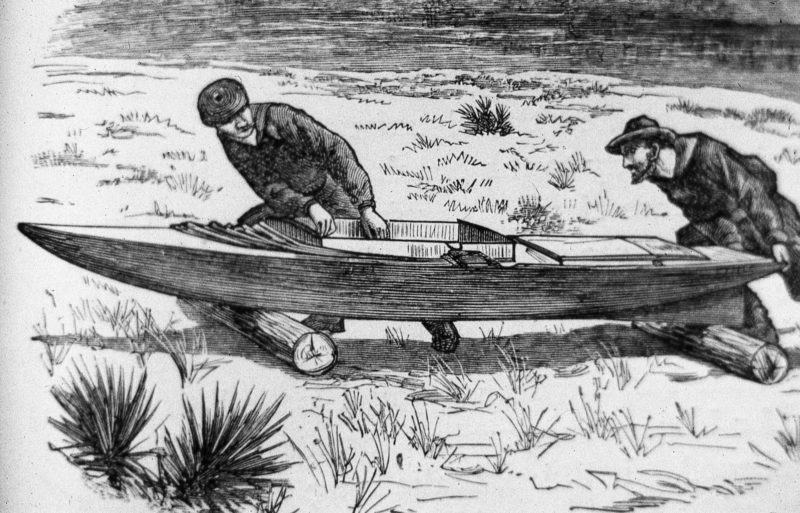

This undated photograph of Bishop paddling MARIA THERESA is the only photograph I’ve seen of that famous paper canoe. Bishop spent most of his time rowing instead of paddling; the outriggers are here folded back to rest on the deck. [Update: Ken Cupery, who once published The Paper Boater (no longer being issued but selected articles appear in Ken’s website, www.cupery.net), notes that the boat pictured here is not MARIA THERESA, which had a much longer cockpit. The photo has no notations and the boat’s identity is unknown.]

After I’d paddled MARIA THERESA’s route from Quebec to the Gulf of Mexico, I caught up with Mr. Bishop at the Riverside Cemetery in Toms River. That was in January of 1984. Two years later I’d be back on his trail, close to finishing my retracing of his sneak-box voyage.

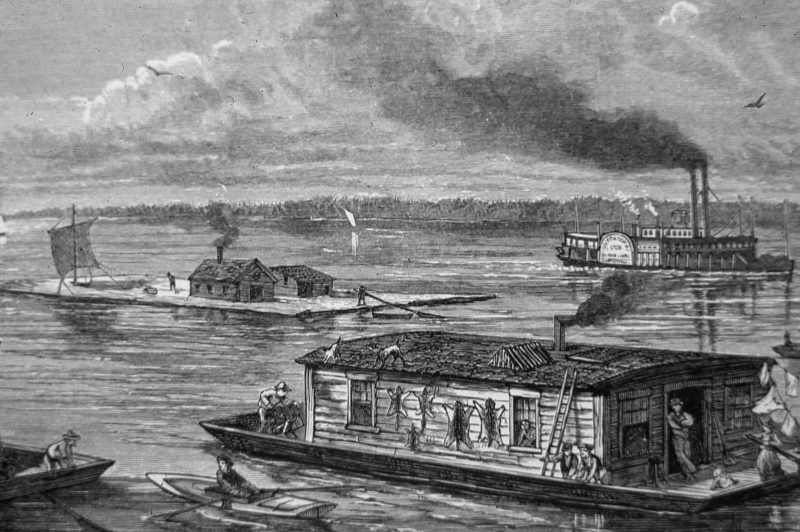

Traffic on the Mississippi River has changed over the last 143 years. In 1876, Bishop’s sneak box, CENTENNIAL REPUBLIC, may have been among the smallest boats on the river, but she was certainly not the slowest.

While Bishop was spending the night in New Orleans, he was discovered by “roughs” and taunted while he was trying to sleep. Having the benefit of his experience, I spent my night in New Orleans tucked deep under a large pier where no one could see me.

The Gulf Intracoastal Waterway wasn’t fully developed in Bishop’s day. Where he had to travel overland, there are now canals.

Bishop traveled 2,600 miles aboard CENTENNIAL REPUBLIC. The route from Pittsburgh to Cedar Key is now almost 200 miles shorter.

When I left New Orleans on a foggy Mississippi River, I had followed Bishop’s two long voyages for 4,500 miles and had another 400 miles ahead to get to the finish at Cedar Key, Florida. In the end, it was over all too soon.

Walter Fullam, whose article on paper canoes helped me build mine, shared with me an abiding interest in Bishop. After I finished my sneak-box journey, I built this model of Bishop’s CENTENNIAL REPUBLIC for him. We remained friends until his death in 2000 and his wife Dorothy and I sent each other Christmas cards for many years afterward.

Bishop did quite well for himself in his later years. He was a successful cranberry farmer and owned over 60 plots of land as well as homes in New Jersey, New York, Florida, and California. In 1880 he was among the two dozen paddling enthusiasts who founded the American Canoe Association. I found this portrait of him in Toms’ River, in the library he funded in his will.

And he did it all without Gore-Tex, wetsuit, or polarized sunglasses, to name just few modern conveniences…

There ya go.

…or Kevlar, sunscreen, or GPS either…

Great story, thanks Chris. Beautifully written and illustrated as well. Inspirational.

Cheers

Another wonderful story, Chris. Your Duckboat is the spitting image of Speedwell, my Phil Clarke Duckboat. The difference is centerboard vs your off-center dagger board.

Thanks again.

Will you be at the WoodenBoat Show this year?

Russ

Thanks, Russ. Your sneakbox and mine are quite similar on the outside, but SPEEDWELL’s traditional construction and my LUNA’s cold-molded construction make for very different interiors. Your boat is much more like Bishop’s than mine, but I opted for a lighter boat and as much free interior space as possible for sleeping aboard.

I won’t be at Mystic this year for the WoodenBoat Show. I’ll be at my desk putting the finishing touches on the July issue of Small Boats Monthly. Enjoy the show!

Chris Cunningham, editor, SBM

What a wonderful story and adventurous lives you both have had! Is it possible to find a copy of Bishop’s travels? Have you published your own story? I’d love to read them.

Thanks, Karen. Bishop’s books are available online: Voyage of the Paper Canoe, Four Months in a Sneak Box, and A Thousand Mile’s Walk across South America.

There are reprints of all three books. Search for Nathaniel H. Bishop. Original editions pop up on occasion at collector’s prices.

I published a few magazine articles about my Bishop journeys, but those may prove hard to find. An article about my paper canoe voyage appeared in Sea Kayaker magazine back in the ’80s and one about my sneak box was published in Small Boat Journal a few years later. The anthology Seekers of the Horizon has a version of my paper canoe story.

When he was 17 years old, Nathaniel H. Bishop sailed from Boston to Argentina and walked across the Pampas and Andes to Valparaiso Chile without speaking the language. He started with $45 and returned home with $50. His journal was published in 1868 as The Pampas and Andes – A Thousand Miles’ Walk across South America.

One of the most amazing (and concisely written) stories I’ve ever read. Thank you, Chris, for sharing both yours and Nathaniel’s experiences.

A much later (1970s) and more modest (circumnavigation of the Delmarva Peninsula) small-boat voyage is described in Western Wind Eastern Shore by Robert deGast. Tusitala is a wonderful book about a 1928 New York-to-Honolulu voyage of the last of America’s square-rigged ships, written by the captain’s son, Roland Barker, who signed on as third mate.

Hey, Chris, great story. I live in West Creek, New Jersey, where the sneak box or devil’s coffin, as Seaman called it, was designed. The Westecunk Creek (crik) runs through my property and the sneak boxes are still used extensively in the area during duck season. The Tuckerton Baymen’s Museum has a large collection of them and for a while were building to order on site. Thanks again, Pat Filardi

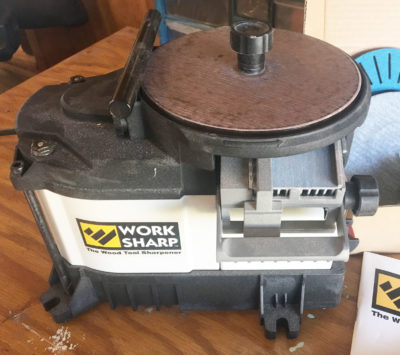

I thought I might share a few photos of my attempts (early 90’s as I recall) at constructing a paper boat. This was a 13’ x 26” kayak of my own design, cold molded in kraft paper, frameless except for the keel, stems, inwales and two thin luan bulkheads. The deck was also of luan, sheathed in paper. Altogether surprisingly rigid. No fiberglass, the hull was coated with epoxy primer and Breakthrough paint (tough and waterproof in those days not now).

I laminated broad strips of paper (3-4 layers) on the bench using Titebond II. These were then overlapped on the form using thickened epoxy as per conventional cold molding. I was surprised to find the hull as rigid as molded fiberglass. The deck structure held the shape. Bulkheads were for air chambers.

Titebond III is good as a sealer for ply and adding a paper laminate: kind of homemade MDO. Full strength thinner than I and II. I’ve used it for kayak paddle blades. But as with most folks a paper boat an interesting challenge. I think we have vastly better adhesives than in Water’s day but perhaps not so with paper. Now that agricultural hemp cultivation is again legal maybe that will change.

The kayak was “retired” a year ago to make room for others.

Ken

San Francisco