In 1982, inspired by Nathaniel Bishop’s book Voyage of the Paper Canoe, I built a 17′ decked cruising canoe with a laminated paper hull and deck reinforced with a yellow-cedar frame. On August 15, 1983, a paddling partner in a fiberglass kayak and I set out to follow Bishop’s 2,500-mile route from Quebec City to Cedar Key, Florida. Almost all of the route is well protected and only twice did we have to go ashore to wait for safe conditions. There was only one dangerous moment that could have turned out badly. It happened on Love Point on the north end of Kent Island in the middle of Chesapeake Bay. Here’s how I recorded it in my journal:

——————-

Thursday, October 13, 1983

Up before light. Gray skies but calm and good visibility. Saw bald eagle—big. Later two more. Geese, heard before seen, came from a cornfield and alit on the water in our path with 7 or 8 white swans with them. Geese leapfrogged ahead of us. Swans a little bolder. Saw white bird like a heron but half the size. Egret?

Made a couple of stops along a marsh. Found a white terry-cloth visor. Stopped at Gratitude Marina [Rock Hall, Maryland]. Saw horseshoe crabs. A man my age working on boats. He tried to find charts for us but at the end of the season nobody has cruising guides. New revised ones out in spring. Gave us route instructions to Annapolis. Nice guy. Checked at Rock Hall Marina. No Charts. Rain. Got ice-cream sandwich.

Crossed bay at the mouth of the Chester River to Love Point, east side of Kent Island. Hard pull across wind southerly, pushing us sideways. Paddling hard 15° to 20° above landing. Stopped quickly and came north around point, heading south toward bridge. Saw orange sand alluvial cliffs. One block of fallen stuff had sand ripples. Took picture of boat and cliff blocks of sand.

Was shooting another when C shouted, “Your boat!” Looked to see the stern buried in dirt. I had cameras in hands. Took two shots. Looked at boat, then cameras, back and forth. Called C. Gave her cameras and told her to keep off, yell if anything moves. Dug out stern and pulled boat free. Felt bottom. No cracks. Got in, kept weight forward. When C and I paddled back with crippled boat, I looked over to her, grinning and said “Neat!”

Paddled north to a beach in front of a house. Rudder bent and jammed. Put ashore and put boats up on a lawn. C emptied gear and spread it to dry. I started cleaning for repair. Left a note at the house’s front door. Back to boat, turned on radio and immediately heard mention of a thunderstorm warning. Turned on weather radio. Severe thunderstorm warning, heavy winds, and damaging hail, 3 to 10 p.m. Uh-oh.

Back at house, old folks. “We need a garage.” “We don’t have anything like that here, but okay to move boats through our yard.” Found big garage and Steve and his wife Charlie [short for Charlotte]. Lucky to get off open ground before hail storm. Steve drove truck down and loaded my boat. Drove to garage. C wheeled hers up [on her cart]. Steve drove us to hardware store for more fiberglass. Back for dinner.

I had pulled ashore at a recess in the cliff that had enough of a beach to get half of the canoe out of the water. The large roller made it easier to move the heavily laden 17′ canoe than dragging it. The fender was a find from the day before as we paddled south on Chesapeake Bay along Maryland’s Eastern Shore. It proved its worth and we carried it for the remainder of the voyage to Florida’s Gulf Coast.

This block of compressed sand was what drew me ashore. The ripples had been preserved beneath strata of more sand since the Ice Age. While I was taking this picture, I heard a muffled WHUMP.

The 20′ tall scarp looming over the stern of my canoe had collapsed, pushing it off the roller and burying its stern. No more than three minutes earlier, I had been standing at the base of the wall, bent over, setting the stern down. If not for a fortunate bit of timing, I likely would have been buried.

I could see the canoe had been damaged even before I began to dig it out. The coaming had split in two at the center and was the end of a crack that angled aft across the port stern deck. Trying to wrestle the canoe free might have caused more damage, so I dug it out with my hands, keeping an eye on the cliffs looming over me.

The break on the port side of the deck was about 5′ long. The starboard side was fractured along about 3′ of the gunwale. I left the sand that was in the cracks to prevent water from flooding the canoe on the short paddle to the north to a safe beach.

Friday, October 14

Took a long time this a.m. to get packed. Stuff was in such a mess. Charlie fixed us cheese omelets, big, with toast. During breakfast her infant son, 6 months old, in walker, was hypnotized by willows in the wind.

Wheeled C’s boat and gear to small point on west shore of Love Point. Windward shore—blowing 15 to 20, 3′ waves and whitecaps, no beach, no protection.

Went back to Charlie’s then walked C’s boat to the other side of the point, 5-minute walk to oyster-dredge place. Met Larry, Bill, and Jim. Led us to beach on leeward shore. Larry drove us back to Charlie and we loaded my boat and the rest of the gear. Said goodbye to Charlie, hugged adieu. So nice. Larry helped us drop off boats. We loaded up and headed out. Stream full of fish.

I carried fiberglass and epoxy with me to make repairs to the canoe, but I didn’t have enough for the damage the landslide had caused. A Love Point family came to the rescue with a garage to work in and a ride to a marine hardware store for the supplies I needed.

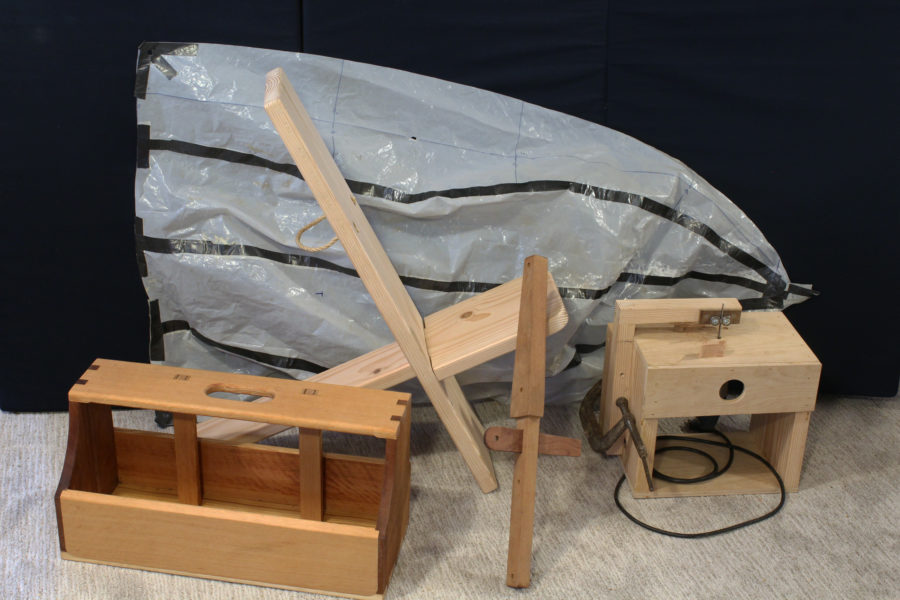

The canoe lasted another 83 days and roughly 1,000 miles with only minor damage and repairs. Here, at Cedar Key, the canoe had fulfilled its purpose.

Looking back on that event, now 39 years ago, I still remember the elation I felt as we paddled away from the landslide. I had read James A. Michener’s novel Chesapeake in preparing for the voyage and knew that islands in the bay inevitably ceded their shorelines to the water. Michener’s fictional Devon Island lost land to the water and eventually disappeared altogether. In the fallen blocks of sand, I could see that had been happening at Love Point, though I assumed that, like many geological processes, I’d never see it in action. These days smartphone video recordings capture almost everything, landslides included, and it’s there for the viewing on YouTube. In 1983, to be present and to experience such an event firsthand was quite rare. It was a stroke of good luck to be at Love Point at just the right time. Much of Love Point’s shore is now protected by revetments of boulders and the sand cliffs have been graded to a gentle slope and covered with grass. The bay and the island have been brought to a stalemate.

I wasn’t at all upset about the damaged canoe. The paper laminate began falling apart even before the voyage had begun and repairs were a constant chore. After the first 500 miles, we stopped in Troy, New York, on the Hudson River and I did an overhaul of the entire hull and put on a new skin of brown paper towels, Handiwipes, and polyester resin. So, fixing the landslide’s damage to the deck was easy. I was pleased the canoe got some impressive scars to carry the Kent Island story.

Without the damage to the canoe, we would have missed the kindness of the residents of Love Point. They welcomed us, sheltered us from a dangerous hailstorm, made it possible to get the supplies the repairs required, gave us a place to sleep, fed us, and sent us on our way as if we were old friends. The landslide was one of the most memorable things that happened on that long voyage. And it led to one of the best.![]()

Enjoyable and exciting. Nice story with very simple sentences that cut to the quick. How nice to find such warm and helpful people. The world is still good.

But a paper kayak? That took guts. Brains?

Very intrepid voyage.

How old is the author now?

People have been intrigued by paper boats for maybe a century, I think due to the cheapness of the material. Early experimenters often used varnish as the binder, and sometimes glue. The boats usually fell apart rather quickly.

I wonder if epoxy might work better. It is flexible and strong as well as waterproof.

I think epoxy would work, but it would have been much more expensive than the carpenter’s yellow glue (aliphatic resin, the original Titebond) I had used. I tried Weldwood Plastic Resin (ureaformaldehyde) for my first hull layup, but it distorted as it cured and became very hard and brittle.

I had to rebuild the hull after 500 miles. I stopped in Troy New York, where paper boats were manufactured in the late 1800s, and I used brown paper towels, Handi-wipes, and polyester resin.