Wherries go back to the 15th century in Britain, where the designation has been applied to a variety of vessels from canal boats, water taxis, naval gigs, fishing dories, and even collegiate rowing vessels. Later, in colonial America, wherries built by immigrants plied the Maine coast, and rapidly became the preferred boat of the Atlantic salmon fishery. These wherries feature a plank keel, which makes it very easy to work the boats on and off the shore, since they stay upright and create a flat surface in the boat for the occupants to move around. Fine waterlines at the stern as well as at the bow provide efficient rowing and easier launching into waves. The sheer flares at the stern and ends in a wineglass transom. The resulting greater volume provides the buoyancy needed to retrieve the heavy anchors used to set fishing nets.

The Duck Trap Wherry was designed in 1980 by Walter J. Simmons of Lincolnville, Maine, as a 16′ pulling boat, traditionally built with white-cedar lapstrake planks over an oak backbone and steam-bent frames, all copper and bronze fastened. The completed boat was to weigh around 175 lbs.

Responding to demand for even lighter boats, Walt created 14′ and 15′ glued-lapstrake plywood versions that come in under a magic 100-lb mark. They were drawn with the amateur builder in mind and require about 300 hours of labor.

Photographs by Pepe Mélega

Photographs by Pepe MélegaThe rowing version of the wherry has widely spaced steam-bent frames to support the glued-lap plywood planking. The sailing version gets stouter sawn frames.

Walt, responding again to demand, added sailing capabilities: centerboard, rudder, and a beefed-up structure. The spritsail keeps the center of effort low to minimize the heeling moment imposed upon the boat’s 4′ beam and low freeboard. This new version was just what I was looking for: a trailerable sail-and-oar vessel that would be easy to build, perform well in light winds, and carry two for day trips on nearby reservoirs.

The sailing version of the wherry has more substantial sawn frames to stiffen the hull for the strain imposed between the mast pressed to leeward and the weight of the crew set to windward.

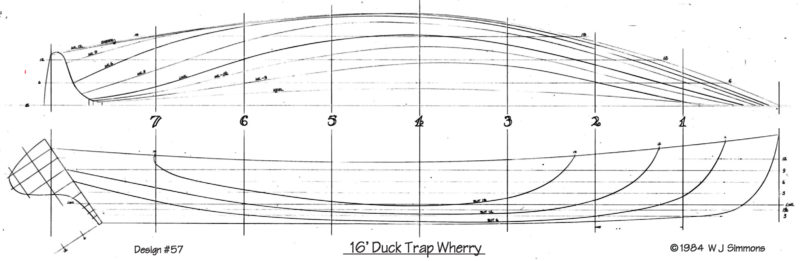

The plans I ordered from Duck Trap are comprehensive and very clear. They consist of a booklet on glued lapstrake construction and four 36″ x 26″ sheets that include lines, offsets, construction details, and a sail plan.

If you don’t want to loft the lines, full-sized loftings are available and printed on a long roll of paper. There is also an e-book for the Duck Trap Wherry available as a download or a CD. It is a detailed guide to the construction and includes instructions for building the wherry in any of the design lengths, 14′, 15′, or 16′, and is helpful to read before ordering the plans to see what you can expect in the building process.

With two at the oars, the wherry trims nicely.

I built a 16′, two-station pulling version to this design back in 2013 as my first glued-lapstrake construction. The plan featured the arrangements for setting the boat up for solo or tandem rowing. After years of happy rowing, I decided to build a sailing version from the same plans. It is important to note that, when ordering a set of plans, one gets the right to build one boat. Any subsequent boats built to the same plans require the payment of royalties to the designer—in this case, half of the plan’s purchase price.

On the first boat I built, I transferred the drawings of the stations to 3/4″ pine boards and used a bandsaw to cut them out. Yet on the sailing version, I used a different approach to gain precision and to become acquainted with CAD techniques. I electronically lofted the stations from the offsets and drew the major parts as CAD files and had them CNC routed. For the molds I used 3/4″ MDF. The keel and most of the solid Brazilian cedar parts that would be used throughout the construction of the boat, such as inner stem and transom as well as quarter, thwart, and transom knees, I also had shaped by CNC router.

The plank keel is an 18mm laminate consisting of two layers of 9mm okoume marine plywood (I used Brazilian cedar plywood). The plans call for 1-1/2″ oak stem and transom knees and 1” mahogany transom; I used Brazilian cedar lumber.

A passenger in the stern throws the trim off a bit when two are at the oars, but the wherry can support the weight of three adults.

The lighter rowing-only version uses steam-bent laminated oak ribs. To give the hull the necessary strength to withstand the stress imposed by the sailing rig, my sailing version has sawn, 1”-thick frames of Brazilian cedar, although one could use white cedar or red oak.

The planking, cut from 9mm Brazilian cedar marine plywood (okoume is specified), is scarfed together to get the lengths required. Since the interior was to be varnished, a detail I worked out was to hide the joints behind one of the frames. The result is well worth the effort, as there are no visible joints on the varnished interior. The sheer is strengthened by oak or mahogany inwales and outwales separated by wooden blocks evenly spaced between the frames.

The sailing version of the Duck Trap Wherry has two rowing thwarts, side benches, and a stern seat. The seat in the bow serves as the mast partner. I combined the stern seating elements in one piece of 9mm plywood and added 10mm teak planks to all of the seats, simulating a yacht’s deck.

Four teak floor gratings cover the flat keelson and keep the crew’s feet dry longer, should water come in over the topside. I prefer the gratings over the 3/8″ x 3″ oak floorboard slats specified in the drawings.

The centerboard, laminated with two layers of 9mm plywood, has a 17-lb lead insert to drop the board when the pendant is eased. The 16′-long, 3″-diameter tapered mast was laminated in two halves made from local freijó wood, which has properties similar to the eastern white spruce recommended by the designer. The 16′ sprit was carved from one single 2″ x 2″ piece of freijó.

Plans detail a kick-up rudder and a fixed version. I opted for the latter, which is more curvaceous and has a classic look. It’s made of laminated plywood and cedar cheeks. Special Duck Trap bronze fittings are an ingenious way to let the fixed rudder rise along a bronze rod if the blade touches the bottom.

The 100-sq-ft spritsail is ideal for our prevailing light winds. The plans call for one reef; I added a second to ensure that the sail won’t overpower the boat if the wind pipes up. In addition, after talking to Walt, I had the sail made with a full batten on the sail foot. This setup gives it a nicer shape, especially when sailing downwind.

I made the 8′ spoon-blade oars to Ducktrap Store plans. It is not a very difficult task to shape them, and they are quite efficient in the water.

The wherry is a fairly light boat—around 230 lbs for the fully rigged sailing version, with all my usual stuff in it—and is easily trailered with my mid-size sedan. At the ramp, it can be effortlessly launched and retrieved from the trailer with its front winch and a roller at the rear.

Boarding is pretty straightforward from the side, and moving around in both versions of the wherry is facilitated by the broad plank keel, which measures 15″ amidships, although the centerboard trunk in the sailing version is a bit in the way. Working wherries were designed to allow the hauling of heavy fishing nets over the side and, like them, the Duck Trap Wherry has excellent stability.

For solo rowing, using the stern station leaves the bow high, an advantage for holding a downwind course. The forward station is the choice for upwind work.

Rowing the wherries is a sheer pleasure. The fine ends create very little drag. It is almost like rowing a competition skiff. I never felt like I was hitting the limit when pulling hard. It takes little effort to make 5 knots, so at cruising it could cover a lot of ground at a satisfying pace. The heavier sailing version of the wherry, even carrying the weight of the sailing rig, performs really well under oars, too, almost as well as the rowing version.

The wherry turns well for course corrections and favors tracking over maneuverability in tight quarters. For tandem rowing, there is enough space between stations to keep out of each other’s way. The plans provide arrangements for tandem rowing for the 15′ and 16′ versions of the wherry.

The boomless spritsail offers uncomplicated sailing and quick furling when it’s time to strike the rig.

For the sailing version, putting the unstayed mast up is a cinch and the boat can be ready to sail in a few minutes. The wherry needs very little wind to be up and running and the spritsail points well to weather, tacking through a very commendable 84 degrees. With 5 knots of wind, it can do 3.5 knots to windward.

The hull was initially intended for rowing and has a low freeboard amidships, so keeping an eye on the leeward rail while under sail is always advisable in order to avoid accidentally taking on water.

On a beam or a broad reach, the wherry performs superbly, easily reaching its predicted hull speed of a little over 5 knots. I’ve even recorded 5 1/2 knots when riding out a puff.

The Duck Trap Wherry is a versatile boat that rows and sails with ease. It’s designed with the amateur builder in mind and requires about 120 man-hours for a standard build. It took me around 300 hours to build the sailing version of the wherry, with a considerable amount of that time spent finishing the boat to a high standard.

The wherry’s classic beauty always draws a lot of attention. Captain Pete Culler had a saying that, “If a boat looks good, it usually is good.” The Duck Trap Wherry is proof of that.![]()

Oliver Ilg, 58, was born in Stuttgart, Germany, and moved to Brazil at the age of 4. He is a physicist with an MBA and worked for the automotive industry from 1985 to 2002, when he joined Sterling Yachts. His father always loved boats, so Oliver had early exposure to them—at the age of 3 he was already rowing a wooden boat. In 1989, Oliver was the project manager for the construction of a 53′ steel sailing vessel for his father. Ten years ago, Oliver started to build wooden boats for himself as a hobby and has kept building them ever since then.

Duck Trap Wherry Particulars

Length/16′

Beam/48″

Draft, board up/5″

Draft, board down/36″

Sail area/100 sq ft

Plans for the Duck Trap Wherry are available from the Duck Trap Store for $65.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

That boat has beautiful lines. The stern is gorgeous. I have always wanted to build one so I could sit in a rocking chair and I could look at the lines all day.

Beautiful boat. The attention to detail looks fabulous. I would love to hear more about the 53′ steel sailing vessel that Oliver helped build for his father, of course, and the subsequent sailing adventures!

Lovely boats from Walter Simmons. I’ve build a few in boatbuilding courses, among which are this Skiff, the Sunshine, and the Newfoundland Trap Skiff. The latter would be nice to show others how sleek these creatures can be. I sailed mine with the two-mast version, but later wanted to have the single-mast setup. I still have the plans, so maybe?

Note that the purchase of plans from many designers provides the the builder with permission to build one boat from that set of plans. To build another boat from the same set of plans, a royalty is due the designer. That charge will be less than the cost of the plans and terms will be provided by the designer in the plans.

Editor

My Christmas wherry by Walt Stevens is in my garage. Heavier built with a lug rig, but rows beautifully too. Unfortunately the drought in South Texas the last few years has made taking her out a little tough with nearby lakes down 40′ to 80′ from normal so we spend a lot of quality time just dreaming until the rains come.

I got in touch with Walter Simmons in paying extra when building a second or third boat from the same plans. Nice fellow! Got a lot of his books too ….

Looking through the photos it seems to me that the stern buoyancy from the wineglass would hardly ever be of any assistance.

A beautiful looking boat but has the wineglass, on this and others become a style preference rather than a practical one?