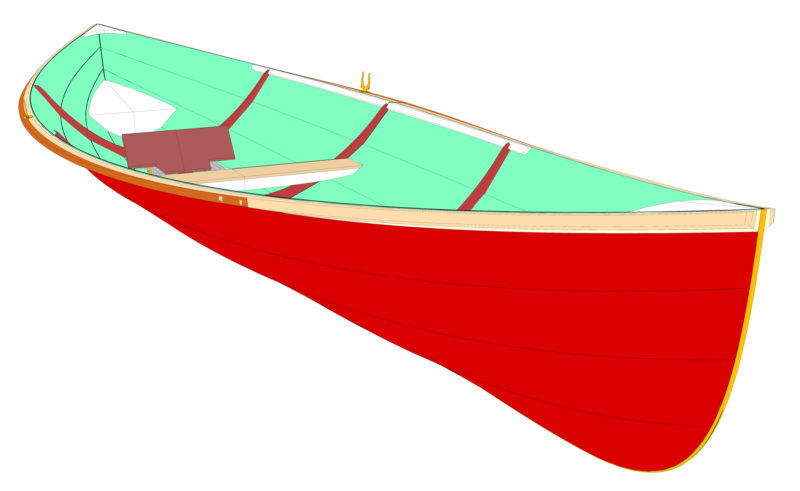

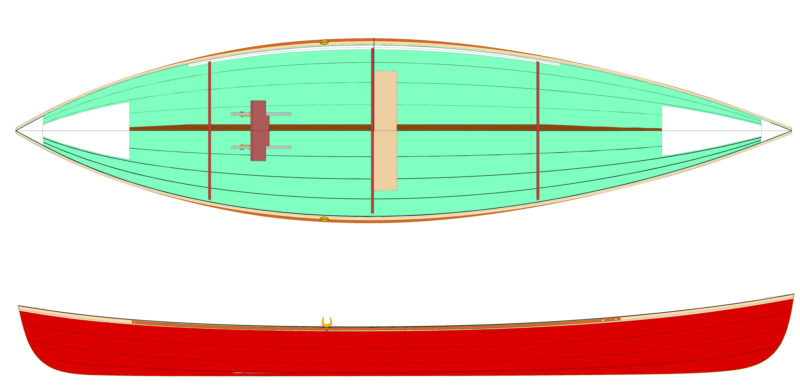

Clint Chase of Chase Small Craft wrote of his Drake Raceboat: “This was the first boat that I designed totally from the numbers.” It’s the third in his series of Drake Row Boats and, at 18′3″, it fits in between the Drake 17 (17′4″) and the Drake 19 (19′2″). While the Drake Raceboat has a familial resemblance to these two American-born relatives, I suspect that there is some Finnish blood in its veins. The fine entry, the ‘midship cross section as close to semicircular as you can get with four wide strakes, and the light laminated frames look a lot like they came from the boats Finns use for racing on their vast network of interconnected lakes.

Christopher Cunningham

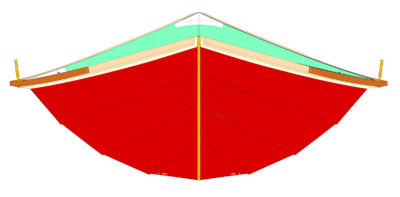

Christopher CunninghamWith no keel and very little deadrise to the garboards, the Raceboat won’t roll on its side when resting on a beach.

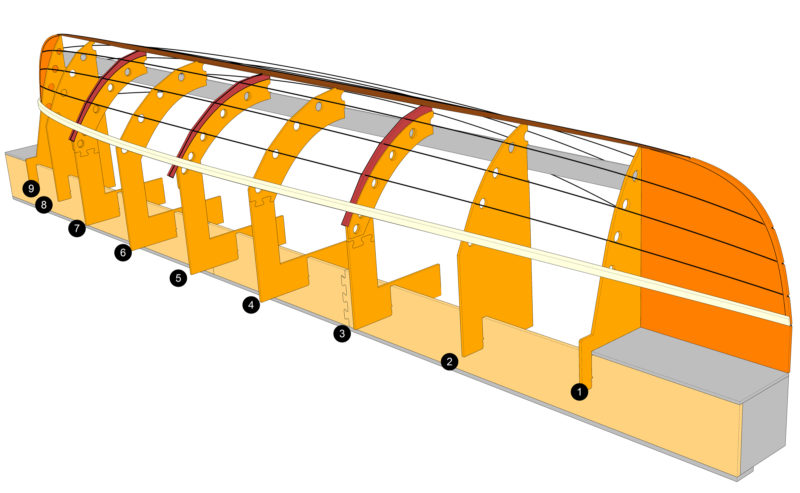

The Drake Raceboat kit includes all of the computer-cut plywood parts for the boat as well as engineered wood panel pieces for the building forms. There are eight molds, all notched to fit mating notches in the two girders that support them. Five of the molds are faceted where the planks land; the remaining three are curved to serve as forms for laminating the boat’s three frames. Eight 3/16” strips are glued up over the form to make up each frame, and after the epoxy cures, the frame faces are planed flat. Placed back on the mold, a template is used to trace the facets for the planks.

Each plank is made up of three pieces of 4mm plywood to be joined with an unusual three-step scarf joint, which has an internal interlocking puzzle joint concealed by the outside steps. The planks have 1/2” laps between them; to keep the limber plywood running fair between molds, a temporary clamping batten is used when gluing the laps.

The inwales, made of 1/2″ stock, extend just past the frames fore and aft. The outwales run from stem to stern and are built up of three pieces, making a distinctive broad flange that stiffens the sheer. The oarlocks rest on pads fastened to these wide rails. While the kit doesn’t include parts for flotation compartments—the instructions recommend the use of float bags instead—the boat I tested had small sealed compartments in the bow and stern. The builders, Jim Tolpin and Oscar Lind of Port Townsend, Washington, asked Clint to provide patterns for the plywood pieces. The compartments were sealed, but at my suggestion were each given a small hole in the bulkhead to allow air pressure to equalize.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe flotation compartments in the ends of this Drake are an option requested by the builders.

This boat tipped the scale at 82-3/4 lbs, a bit over Clint’s predicted 75 lbs. Jim and Oscar made some modifications in addition to the flotation compartments that would account for the additional weight. They substituted solid mahogany for the plan’s plywood seat, breasthooks, and stretcher; added 1/2″ brass half-oval running from stem to stern and 6’ lengths along the gunwales amidships; and applied several extra layers of paint. Even with the extra weight, their boat seemed feather light. The mahogany breasthooks made solid handholds for a tandem carry.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamHere, with builder Jim Tolpin at the oars, the Raceboat looks quite voluminous, but the breadth at the sheer belies the slender waterline.

I’d heard from the builders that the Raceboat was rather tippy, but I think much of their uneasiness could be attributed the boat’s wide beam. Getting aboard requires a long step to plant a foot on the centerline and a long reach to get a hand on the far gunwale. The boat’s light weight and rounded midsection make it quick to react to weight planted off center. I’m 6′ tall and have limbs long enough to make the stretch and keep the boat flat. Any rower seated and centered on the thwart will likely feel stable and secure.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe footboard is adjustable for a wide range of lengths and provides a broad and solid base to push from to put power into rowing.

The rower’s bench is a fixed 10-1/4″-wide thwart that’s set on a short riser glued just forward of the ’midship frame. The footboard is pinned to a pair of 24″ rails with holes every 2″. Although the increment works well enough when adjusting for leg length, a spacing of 1″ between holes would offer not only finer adjustments but also the ability to set the footboard at a different angle to suit the rower. That’s a minor point and an easy modification to make while building the boat; the structure of the footboard is quite solid and provides a foundation for a powerful stroke.

The boat is quite easy to accelerate; a half dozen strokes and it was off and running. I did some speed trials in a marina where there was neither current nor wind. With a lazy, relaxed effort I easily maintained 3-3/4 knots; a sustainable exercise pace brought the speed up to 5 knots.

Christopher Cunningham/Jim Tolpin

Christopher Cunningham/Jim TolpinRowing a fast boat sometimes requires stopping quickly. Driving the feathered blades in does the job. The light weight of the Drake Race Boat makes this maneuver possible without putting undue strain on the rower.

It wasn’t easy getting a steady reading on my GPS while I was doing sprints at full effort. Even though the Raceboat is rowed from a fixed thwart rather than a sliding seat, the shifting of my weight as I leaned aft to the catch and forward at the release created an equal and opposite reaction in the boat, dramatically slowing it down on the drive and speeding it up on the recovery. Fluctuations in speed may not be quite so noticeable in a heavier boat, but in the lightweight Raceboat they spanned at least 1-1/2 knots. I’d estimate that the boat’s sprint speed averages out around 6 knots. It’s a fast pulling boat.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe flare of the sheer strake and the wide flange of the gunwale are evident when the boat is viewed from an end.

To make the most of the Drake Raceboat’s speed, it’s essential to have good technique and a good pair of oars—spoon blades, of course, for a good purchase, and a low swing weight for quick recoveries. On my second day of rowing trials, Tom Regan of Grapeview Point Boat Works delivered a new pair of 8’ spoons. They were a good match for the Raceboat. With slender blades that were nimble in and out of the water, the oars could keep up with the boat.

The Raceboat tracked well and there was no need to correct its course on a straight run. It also responded well to turning strokes and was easy to spin around in place as I pulled one oar while backing the other. There wasn’t much wind during the weekend when I rowed the Raceboat, perhaps about 8 knots but while I was rowing across the wind I didn’t feel the boat had any tendency to weathercock. The wind was offshore and made the water flat, but I did have a few powerboat wakes to drive through. The Raceboat cut through them smoothly and they passed by without much effect on the hull.

Christopher Cunningham/JimTolpin

Christopher Cunningham/JimTolpinPushed hard, the Raceboat maintains its trim well and makes little fuss passing through the water.

The Raceboat I rowed arrived on a small trailer but could be set on roof racks. I regularly cartop a 100-lb tandem decked lapstrake canoe, by lifting one end at a time. A compact SUV like mine provides enough of a span to keep steady an 18’ boat as light as the Raceboat, which is much lighter and easier to manage. If your back and height aren’t a good match for the lift, a trailer is the better way to go

While the Drake Raceboat is designed “for the greater speeds in race conditions,” you don’t have to compete to appreciate the boat. It will give you an exhilarating workout and reward improvements in your stamina and technique, but it’s not so high strung that you can’t take it out for a relaxing outing.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Monthly.

Drake Raceboat Particulars

[table]

Length/18′3”

Beam/48.5″

LWL/17′

Depth/14”

Displacement/306 lbs

Hull Weight/75 lbs

[/table]

The Drake Raceboat will be available as a kit in November of 2017 from Chase Small Boats. You can also build from the plans package, which includes templates for the molds and forms for the bow and stern—planks will require spiling.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

It is good to see new design ideas coming out like this. Of course we would worry about its tenderness but the same complaints are made about the Adirondack guide boat. I always advise customers to hold onto the gunwale on boarding as overbalancing is the only way of falling in. My studies indicate that for cruising a waterline length of 16′ or less is best to reduce wetted surface. Since we cruise at about 4 knots, wave making does not cause much resistance compared with boat friction in the water. I am inclined to think a smaller person or a female might cruise more easily with a 15′ boat. By the way we race around Dangar Island in Sydney and the best speed for the event in a Herreshoff rowboat (16’5″ waterline length) is 5.6 knots.

Yet another example of a beautiful boat designed by a talented Clint Chase. I love his use of new methods (CNC) and techniques (three-step scarf) to produce timeless designs with a classic look. Keep up the good work!

Thanks, Jim. And thanks to Mr. Tolpin and Mr. Lind for really building a beautiful prototype. Thank you Chris for putting this review together.

There is also a 20′ set of lines prepared for kitting, as requested by a gent in the SF Bay area. I think that will go like smoke, too.

The boat is beautiful but the oars, to give it justice, should be of the spoon type. Of course these may have just been just to hand for the photos. However I also notice that the gap between the handles inboard seems to be larger than would be proper. I also believe it more proper that the oars should be drawn inboard to stow rather than swinging the blades to sit on the seat depositing water. “Efficient rowing” is discussed in detail on my website along with articles on rowboat design and making an oar. I hope this little contribution has been helpful.

We had several pairs of oars available when I rowed the Raceboat.Two would fit the Gaco locks that the boat was equipped with. One pair

We had several pairs of oars available when I rowed the Raceboat. Two pairs fit the Gaco locks that the boat was equipped with. One pair, which appears in the photos without leathers, was about 7′ 9″ in length with blades that were beyond spooned. They were “cupped” and hollow between the blade edges. I didn’t care much for the length or the blade shape. The following day, Tom Regan of Grapeview Point Boat Works brought a pair of 8′ spoons. They appear in the photos as the pair with leathers. We reviewed his oars in October 2015 issue. Clint Chase designed the boat to be rowed with 8′ 6″ oars. The 8-footers worked well, but 8′ 6″ oars would have given me the inboard length that I prefer and that John advises in his comment.

I found this article to be very interesting as I am always looking to try a new rowing boat. This is a decent looking craft. I found the oar talk interesting also as I’m looking for another set of oars for my Seaford Skiff. The tenderness they mention reminds me of the Alden I had. I don’t use a floating dock.

Very interesting article. Boat is definitely a good looker. The tenderness worries me also as I get in my Seaford Skiff from the dock, not a floating dock. I am contemplating another set of oars and contacted Pete at Adirondack Rowing.

One way that I board tippy boats is over the end. Sounds a little weird, but it is basically crawling into the boat.Bend over the end, slide the hands down the boat as far as you can then dive, in staying as low as you can. Works best if you have a deck in the end like my ducker or a bow seat like my dory. I think someone showed me this launching a guideboat from a boat-house ramp. You push the boat off the ramp at the same time.

A variant on Ben Fuller’s bow-boarding technique was developed on the spur of the moment by my exuberant five-year-old (now fifteen years ago) in a canoe on the Concord River in Concord, Massachusetts.

It wasn’t in a tender boat, I grant, because the canoe was already well-ballasted by having me in the stern. We’d beached it, square to the shore, and then when it was time to go, son Tom said he wanted to be the one who shoved us off.

So I climbed in (canoe still hard aground) and made my way to the stern seat without incident—which did unweight the bow enough that Tom could move it easily, and then it was Tom’s turn.

He gave a tremendous shove until he was in shin-deep water, and then flung himself bodily crosswise over the bow where it was no more than 1′ wide, so about 18″ of him dangled out over water in each direction. Then, as we glided briskly on out into the deep middle of the river, he sorted himself out parallel within the hull and took his seat.

Looks good, but I’d like such a light boat as this to also be able to rig for sail.

I’ve rowed the DRB 18 quite a bit, and then built the larger DRB 20 this past spring. In my experience, the tenderness is a benefit in feel without being a nuisance in practice. You can easily slide the oars in, rock back and forth, and not get close to submerging a gunwale. The secondary stability is really impressive, and part of what makes this boat such a great “both/and” solution. And the thick rails mean that waves, wakes, and splashes are almost never a concern – even in 15 to 20 knots with stacked seas.

Like Ben, I usually enter from the bow and just walk up the keel with my hands on the gunwales, but I have entered from the beam and it’s no problem. My boat has large outriggers, which makes docks challenging, but with standard gunwale-mounted or folding oarlocks, I don’t think it would be a problem.

Bottom line, I love these boats. I’m extremely pleased with my sliding-seat DRB 20, but the fixed-seat DRB18 is a treat in its simplicity and effortless speed.

Wonderful accomplishment, Nate.

That secondary stability was quite striking to me, too, one day when I was given a traditional Norwegian 19′ fearing, with sprit sail, to play with in Oslo Fjord. It had a similar quarter-circle frame section amidships, and when you’d begin to roll it, the whole lower side would just lie down on the water, and it wouldn’t roll further.

I had spent a lot of time in Tech Dinghies, which handle delightfully but are relatively bathtub-shaped in section, and if you’ve rolled them far enough for a rail to approach the water, you’re courting a capsize. But in this thing, the harder I pushed it the stiffer It got. I could go barging along with the rail only 3″ off the water and not even worry about it.

Clint Chase: “This was the first boat that I designed totally from the numbers.”

Does this mean that you numerically designed the boat before creating drawings? Is this a purely mathematical technique, or are you using “numbers” derived from algorithms in a computer program? Your Drake raceboat is obviously well thought out; a very smooth, continuously curved multi-chine design.

I routinely use a technique based on mathematical equations which I started in the early ’70s, before programs were available, but have not read of anyone else using a similar approach. Of course, for me it is purely a hobby. I enjoy the accuracy of perfectly fair curves. Now building my 12th design.

Some observations about rowing: Years ago, I was rowing a Bolger Light Dory on Bellingham Bay against a stiff breeze–probably 12 knots, with plenty of whitecaps. I was in company with a Row Cat–a catamaran with a sliding seat and very skinny hulls. Having recently read Bolger’s comments about rowing against sea and wind, I was using a short, quick stroke, and was able to stay with the Row Cat over several hundred yards. I was also handicapped by the ill-fitting department-store oars on the dory, as they were much too short.

I have come to doubt the benefit of a sliding seat with very long oars. My “reasoning” (yes, I will boldly call it that) goes something like this: If you scull a boat over the stern–wiggling the oar back and forth–you can propel the boat pretty efficiently. All the thrust comes from the water sliding rearward off the end of the blade. In fact, this effect happens with ordinary oars as well, though probably less so with spooned or cupped oars.

With the extra long stroke you get with a sliding seat, the first part of the stroke is going to be accelerating some of the water forward, which will tend to retard the speed of the boat. The effect will vary in intensity up until the oar is at right angles to the centerline of the boat. The desired thrust will build until the oar reaches farthest aft. The sculling principle will be in play throughout the stroke, partly retarding forward progress at first and then augmenting it.

I wonder if anyone has tried sliding-seat rowing by starting the stroke farther back than is usually done.

I have found the same principle to occur in padding a kayak against wind and waves. Beginners tend to take a long powerful stroke (as I did when I was first learning) thinking to muscle the boat through the resistance, which can be considerable In those conditions, I have found a short, quick stroke to be much more efficient, and a lot easier on the body and less tiring. Part of the benefit here comes from the fact that almost continuous thrust results, (I tend to think of it as steady pressure on the kayak) with less time spent (wasted) swinging the paddle through the air to set up for the next stroke.