We pointed offshore into a wall of fog, following a compass bearing until a steep hump of granite appeared, rising from the foggy sea, topped with spindly spruc—a sumi-e haiku illustration rendered with a few deft strokes. After pulling our kayaks onto the sand between the smallest islands, we carried our food bags up onto a slab of granite and made our lunch. The low-lying fog was dense enough that we couldn’t see beyond the ledges just offshore, but we could feel the warmth of the sun on our skin. As we ate, the chug of a motor slowly approached and a man’s voice, tinny in the still air, floated in the fog, describing the remains of a prehistoric village now submerged somewhere beneath the boat. He sounded vaguely familiar.

“Sounds like Garrett,” Rebecca said, and I recognized the Maine accent, the cheerful, curious inflection of the mail-boat captain with whom we’d often played Pickleball over the last winter.

I said, “Guess we’re all missing Pickleball today.”

“Summer.” Rebecca spread hummus on a cracker. “No one has time.” Normally we wouldn’t have had time either. We’d owned an art gallery in downtown Stonington for a dozen years, and during idle moments I’d stand by the window, gazing out at the archipelago, imagining a trip such as this: roaming the Maine coast in our sea kayaks, camping on the islands.

The boat passed unseen, Garrett’s voice overwhelmed by the motor, then that fading until we could no longer hear it either. Rebecca lay back against the granite. “I’d be happy to stay here tonight.”

“We could,” I said, but it was the second day of our trip and we’d only paddled a couple of hours and I still felt restless, wanting to put at least a few more miles behind us.

The fog finally dissolved, and the islands ahead were revealed like stepping stones. We launched before the haze could return.

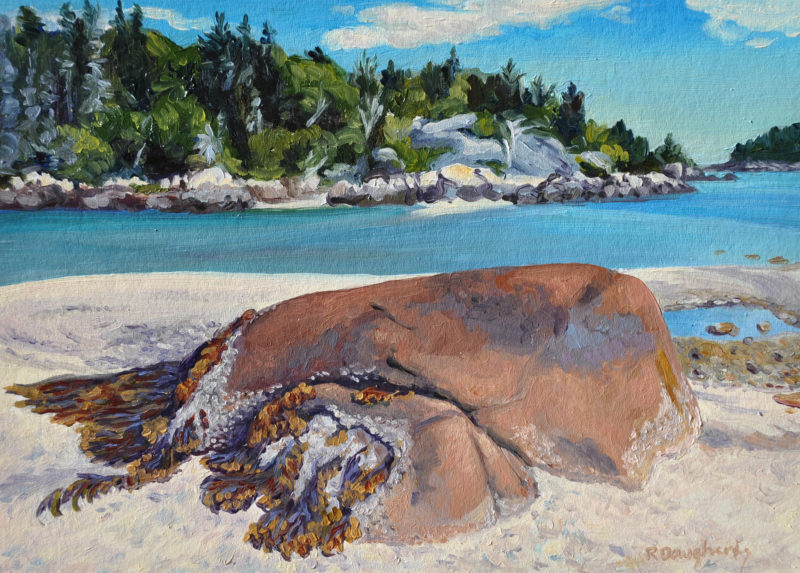

We spent a couple of nights camped off of Stonington and on the Fourth of July, a summer day with fair-weather cumuli mirrored on the glassy swells, crossed East Penobscot Bay. Deer Isle lay behind us as we paddled four miles of open water toward the islands near North Haven. Our kayaks, laden with gear, sat low in the water and were slow to turn, but once in motion their momentum made the miles go by quickly.

We landed on Calderwood Island and pitched the tent, and after dinner, we sat on a ledge as the sky grew dark, gazing over the bay we’d just crossed. Stonington was a dark shape on the horizon until a lone firework lit the sky, followed half a minute later by the faint report.

Another firework exploded, a brilliant magenta chrysanthemum, and then another. We sipped our tea, watching until the finale, a half-minute of bright, silent chaos, was reflected in streaks across the bay followed by a thunder that echoed long after the last explosion faded. I lay back and felt the warmth of the granite ledge beneath me. The stars shone, crisp and clear.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

Rebecca and I wanted to paddle along as much of the Maine coast as we could. With no home or job to return to, we had all the time we wanted, and were limited only by the seasons and our bank balance. We’d decided our trip would be more about spending time in places we liked than covering miles.

Photographs by Michael and Rebecca Daugherty

Photographs by Michael and Rebecca DaughertyJust off Vinalhaven, Ram Island is a tiny islet surrounded by granite ledges. It was one of the islands we visited twice, both as we headed west and later on our way back east. I busied myself with chips and hummus and dinner (most likely a curry) while Rebecca painted the trees behind me.

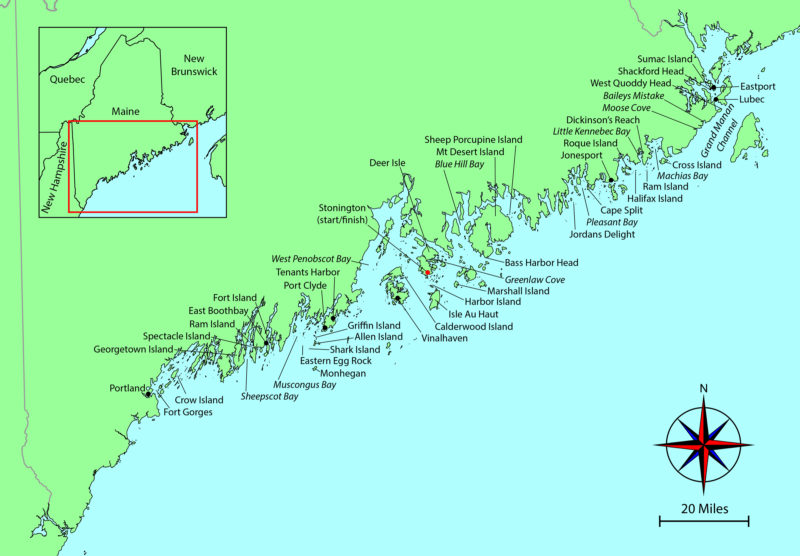

We’d started at Deer Isle, where we had lived and worked for 14 years, and we planned to paddle a big figure-eight: first down to Portland and back, and then up to the Canadian border before returning to Deer Isle. We’d have time to linger in our favorite places and visit many of them twice. It wasn’t until our sixth day of the trip though, when we decided to take a foggy day off and do no traveling at all—what we called a zero day—that it began to feel like the trip we’d imagined. On Ram Island, a tiny islet west of Vinalhaven in Hurricane Sound, I pitched my hammock between a couple of scraggly spruce trees while Rebecca dug her art materials from her kayak. The fog lingered, and the day passed like a dream, the church-like chime of a bell buoy tolling in the wakes of invisible ferries.

The spruce trees atop a granite ledge caught Rebecca’s attention for a 5” x 5” oil on panel, titled “Ram Island”. The scene here is the backdrop in the photograph above of me cooking dinner.

The next day we crossed West Penobscot Bay and traded idyllic solitude for a night at a campground, topping-off our drinking water, recharging batteries and getting our first showers in a week.

We meandered down the coast, camped on an island off of Tenants Harbor, and then on another in the middle of Muscongus Bay. We’d wake before sunrise, but we were often slow to launch, especially if the island had a good spot for a hammock. If it did, I’d linger with my coffee and catch up on notes and reading, while Rebecca roamed with her sketchbook. Hauling gear and boats down to the water took long enough that, by the time we launched, we’d be a little exasperated by the effort and eager to get moving. We’d paddle a dozen or so miles to the next island. We camped only at designated campsites, most of them stops on the Maine Island Trail.

After another zero day, tucked in the Damariscotta River on Fort Island, we paddled back out the river. Along the way we refilled water containers at the firehouse in East Boothbay, and picked up a few supplies at a convenience store. We could carry almost a week’s supply of fresh water with us, but we always had resupplying in mind. Each day we tried to find food and water along the way to our next camp.

A storm threatened as we crossed Sheepscot Bay on the approach to Reid State Park on Georgetown Island.

With a storm approaching, we let the flood tide give us a push up the Sheepscot River and camped beneath massive oaks on an islet no bigger than a tennis court off of Spectacle Island. The next morning, we headed out the Sheepscot in a cool, soaking rain. At Reid State Park, on Georgetown Island, we passed beneath the rocky bluff of Griffith Head, where a couple of coin-operated binoculars stood like massive silver Viewmasters anchored atop swiveling iron stands, pointing seaward. A few intrepid visitors were afoot up there, hunkered beneath raincoats. We passed below their perch, paddling, for a change, with the wind behind us.

Bangs Island, not far from the Portland waterfront, is one of many Casco Bay islands in with public campsites. Worried about ticks in the taller grass, we camped on the beach and worried instead about the rising tide. Neither the tide nor ticks turned out to be a problem. Despite worrisome news reports about rising populations of ticks and increasing incidents of tick-borne illnesses, we found only a few ticks all summer.

After two weeks of wandering down the coast, we arrived at Casco Bay, intent on getting a glimpse of the Portland waterfront before we turned around and headed back, but with the fog, there wasn’t much to see. The occasional rumble of a ferry out in the soup discouraged us from poking around blindly in busy channels, so we contented ourselves with a few zero days on islands near the city.

There are at least 15 Crow Islands along the Maine coast. This one is in Casco Bay, just off of Great Chebeague Island. Aside from the sandy beach that’s not swallowed up by the high tide, we loved the sprawling oaks, which gave me a good spot for my hammock.

Rebecca painted. I swung in my hammock. We finally made it to Fort Gorges, a granite-block Civil War-era fortress guarding Portland Harbor, and the fog cleared long enough for a glimpse of the city, but we were glad to get back to 100-yard-long Crow Island, with its sprawling oaks and a pair of sandy crescent beaches. And, having made it to Portland, we gradually lost that feeling that there was anywhere else we needed to be.

The water was less chilly here than it was Downeast, and during the afternoon we took occasional swims. I retreated to the hammock to dry in the sun, and we waited for a mid-day change of the tide to begin our trip back east.

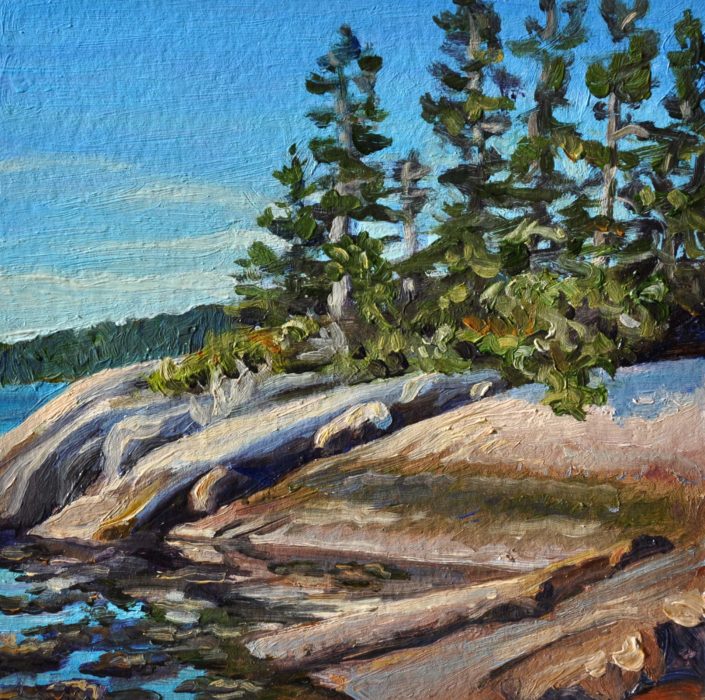

This 5” x 7” oil on panel, “Low Tide Sandbar, Little Hen Islands,” is one of the small paintings Rebecca did on location with the intent of using them as studies for larger paintings.

We zig-zagged along the coast, up the New Meadows River for a visit with old friends. It felt good to rinse-away the salt and grime, to wear dry clothing, socks and shoes, and to eat in a restaurant, but I began to feel uneasy until we were back in our boats the next day, traveling once again. After a night on Ram Island in the Sheepscot, we paddled a long day to Muscongus Bay, and there spent three nights, each on a different island as a storm passed through and left us perfectly poised with calm weather to get out to Monhegan, an island community some 6 miles out to sea from the nearest coastal island.

Eastern Egg Rock, the island we floated alongside, was a treeless hump of rock, only a few acres, ragged with weeds and tangles of washed-up driftwood, and reeking of guano. A heap of lobster buoys lay beside a makeshift plywood sign: TRADE. Next to it stood another sign bearing a red drawing of a lobster. A young woman suddenly emerged from one of two tiny weathered outhouse-like buildings. Carrying a net, she raced down the ledges and swept it over a puffin that had just landed. A young man emerged from the other blind and helped her, kneeling over the captured bird.

A group of puffins swam away from the couple, toward us. The birds were always smaller than I expected, but their beaks looked too big for their bodies, and too brightly colored, like oversized masks colored by a child. We’d followed a string of islands pointing the way to this last solitary rock that separated the mouth of Muscongus Bay from the open Atlantic, and we floated in our kayaks, watching the puffins, sheltered behind the island from the bigger swells beyond. We had about 6 miles of open ocean between us and Monhegan, our next landing, and, at some point, I would need to pee. Landing on Eastern Egg Rock, a bird sanctuary, was prohibited.

We ventured from the lee and paddled into the swell. Monhegan lay on the horizon, but we veered southeast, toward Shark Island—a mile and a half distant— another treeless, fin-like rock pile rising from the depths where the open ocean swells reared and broke through a sieve of jagged rocks and boulders. By now, my plans for a bathroom break had turned into a desperate hope I could get there in time. There was no obvious landing spot, but I told myself I’d made surf landings on rocks before, though not in such a heavily laden kayak.

Rebecca asked, “Are you sure about this?”

I answered by putting my helmet on and aimed for a nook in the lee side of the island where the waves wrapped around and met in a jumble of slippery boulders. Getting out of the boat went well enough, but, ready to paddle again, my relaunching took a few tries as dumping waves filled the cockpit. Finally, I paddled back out, soaked and a little bruised, and came alongside Rebecca. We pointed our bows toward Monhegan.

The swells around us, glassy smooth, reflected cotton-ball clouds. Ahead, a pair of distant blue hills gradually resolved themselves into two islands. Storm petrels skimmed just over the waves, dipping into the troughs; gannets arrived and scared the other birds away.

Soon we could make out the lighthouse atop Monhegan, then the houses below it. Nearing the island, we paused at some ledges where we encountered a pair of kayakers: a boy, followed by his mother, who was paddling with a toddler on her lap. She asked, “Did you just paddle from the mainland?”

“Yeah.” Behind us the mainland was a low, dark line on the horizon above the broad stretch of ocean we’d just crossed.

She sighed. “I’ve always wanted to do that.”

I felt a little pride. I’d always wanted to do it too. And now I had.

After lunch in the village, we paddled around the island, beneath the 150′ cliffs and bobbed in the southeast swell, but we didn’t linger. We still had far to go. There’s no legit place to camp on Monhegan, and the lodgings were out of our budget. Besides, we were lucky to have the good conditions for paddling open water and that could change very quickly. At the north end of Monhegan, we aimed north, across six miles of open ocean toward Allen Island, and the protection of the coastal islands.

The conditions had indeed changed overnight. We woke on a scrubby islet called Griffin Island and rode fat, lively following seas into Port Clyde for a few groceries. We let the wind and waves push us another dozen miles to the campground where we’d stayed three weeks earlier.

By the next day, the weather was perfect again. West Penobscot Bay stretched ahead of us, an undulating plane reflecting a pale sky. Beyond it lay a group of low, dark shapes more than 5 miles away. We pointed our bows toward them and fell into our familiar rhythm.

The persistent mid-tide currents pushed us inland, to the north, but we attempted a straight line by pointing up-current, keeping a range on the faraway cliffs and lobster buoys ahead of us. When we reached a buoy, we’d line up our next range.

In the swells, Rebecca and I often paddled too far from each other to converse, but when she drew near she asked, “What do you want to do when the trip is done?”

I didn’t have a good answer. I’d been gazing at the mirages emerging in the steamy atmosphere. Islands beyond the horizon appeared as if floating in the air like clouds.

We had both worked long and hard to be able to take a summer off and take a trip like this one, but we hadn’t talked much about what we would do afterward. September hung beyond the horizon like an island we couldn’t yet see, and most of the time we just focused on what was in front of us.

“Right now,” I said, “I don’t want this trip to end.” Rebecca smiled.

Goose Rocks Light, built in 1890 at the entrance to Fox Island Thorofare, north of Vinalhaven, is one of several “spark-plug” lighthouses seen along the Maine coast. It is still an active navigational aid maintained by the Coast Guard, but it’s now owned by a non-profit that maintains it with funds generated by nightly rentals.

We spent three nights camped on islands around Vinalhaven, and then took the long way back to the Stonington archipelago, crossing the mouth of East Penobscot Bay and circling Isle au Haut, before paddling 1-1/2 miles to Harbor Island, a 6-acre knot of woods fringed by gentle slopes of gray granite. From our camp we could see the familiar glow of Stonington in at the northern edge of the night sky.

South Little Hen Island lies off Vinalhaven in Seal Bay, a popular anchorage. We took a zero day here and idly watched cruising boats come and go.

The next day, paddling toward our home town after a month of kayaking reminded me of so many other times I’d returned home from countless shorter paddling excursions. But we weren’t returning home. We were stopping only briefly for fresh water and whatever groceries we could scrounge from the shoreside convenience store. We dropped in at the library, just across the street from the water, to say hello to the librarian, a friend of ours, and she passed along a massive zucchini that someone had left her—a dubious gift in summer when everyone with a garden has more zucchini than they need—but it would feed us for the next couple of days.

After another night in the Stonington archipelago, we crossed Jericho Bay in the fog to Marshall Island, the largest uninhabited island on the eastern seaboard. We camped with some friends, and the next day paddled with them north. We left them finally and turned toward Greenlaw Cove, where we’d begun our trip more than a month earlier. We spent the next couple of nights in the guest room of the friends who’d loaned us their cabin over the previous winter. In between rinsing our gear and picking up groceries, we were immersed in our hosts’ busy summer social life, taking another guest for a paddle, and chatting for hours over brunch. I became increasingly restless, and when Rebecca and I were finally on the water again, it felt like a miracle. We hurried the 10 miles across Blue Hill Bay, island hopping to the south end of Mount Desert Island.

A crowd lined the rails of the walkway below the lighthouse at Bass Harbor Head, and farther down they dotted the steep rocks with splashes of color like confetti, which, as we paddled closer, turned out to be visitors at Acadia National Park. We paddled close to shore, alert to waves that lifted us as they passed and crashed into the rocks. People waved at us as we passed and Rebecca, always polite, waved back. I felt awkward, as if I’d joined a parade, and focused on my paddling.

Beyond the lighthouse, there were no crowds and on an isolated stretch of the bare granite shoreline we saw a man, alone, stepping from rock to rock. He shielded his eyes from the sun to watch us pass. I thought of him as a traveler like us, and waved.

Some islands have only a thin layer of soil supporting a dense spruce forest, like this one in Pleasant Bay.

Beyond Mount Desert Island, the coast was more remote, with geographical features named for the ships or sea captains who had foundered on them. Halifax Island, 7 miles northeast of Jonesport, was named for the British schooner that broke-up on the rocks there. Baileys Mistake, a harbor 6 miles from the Canadian border, was named after a Captain Bailey who ran his lumber schooner aground at the harbor entrance; rather than face his employers back in Boston, he and his crew settled there, building homes with the ship’s cargo. This coast is steeped in such mythology. The lighthouses along this stretch of the coast speak of fog, shipwrecks and loneliness. The tides and currents are more extreme, and the sea is less predictable here and intimidating, but this coast felt larger than life and there was something about it that resonated with me. I felt at home.

Campsites were scarce, and we paddled longer days to get to them. We rounded peninsulas that jutted into the sea far from the villages that lay at the heads of long estuaries. In Jonesport we filled water bags and bought what useful things we could find at the shoreside variety store. Everyone we met looked right at us, smiled, and said something encouraging. We paddled 11 miles to Ram Island, a grassy hilltop barren of trees, inhabited by a pair of black-faced sheep who tolerated us from a distance. From our camp on this 1/4-mile long speck of land, the broad expanse of the Atlantic stretched to the south beneath a vast, empty sky. We watched the sun dwindle into the horizon clouds and almost immediately the fog appeared, further separating us from all we’d left, reducing our world to a hump of grassy rock.

As the sun set on Ram Island, Rebecca painted the islet’s moss-draped trees. The longer we spent in a place, the more Rebecca found to paint.

At around noon, the fog surrounding Ram Island finally cleared and we could see Cross Island, four miles distant and rising from the peninsula beyond it north, of 26 radio towers, some nearly 1,000′ high, built by the Navy to communicate with submarines operating in the Atlantic.

We got to Cross after an easy paddle: a welcome break, since our next day would be the toughest. Cross Island was the last stop before the Bold Coast, a 20-mile stretch of formidable, cliffy shoreline overlooking the Grand Manan Channel, known for its tricky currents and lack of places to land. From our campsite, we planned our moves for the next day and stared out across the narrows, where the fog had obscured all but the tops of the enormous radio towers, their red lights pulsing through the gloom.

In the morning, already shivering from a steady rain, we paddled across the narrows and headed northwest along the Bold Coast, passing seals flopped upon ledges like beanbag toys. The current was against us, so we stayed near shore, following a twisting path of rougher water where the back eddies could help us along. The near-shore rocks formed rockweed-draped mazes; cliff-lined slots rose up into the clouds. “You warm enough?” Rebecca asked.

“Yeah,” I said, but mostly out of habit. I was looking forward to our break. After nearly three hours in our kayaks, we finally landed at a cobble beach just before Moose Cove – just long enough to get into dry clothes and eat.

By now, the tide had turned and the flood’s current would be in our favor, but strongest well offshore. We lingered below the cliffs that rose straight up from the sea to disappear into a layer of fog. At the head of a rock-strewn cove lay an old wreck of a fishing boat. Layers of orange-red paint had peeled away from a bow and its stern had been torn off, presumably by the storms that pummel this shore. A quarter-mile offshore a whistle buoy hooted; we could barely see it.

The fog was always thick when we passed through Quoddy and Lubec Narrows. This time we had a strong current behind us that buoyed us quickly past the Lubec Channel Light.

We finally left the shore and paddled east into the fog to catch the current, leaving the cliffs in the mist behind us. The lighthouse at West Quoddy Head lay invisible five or six miles distant. The lobster buoys showed us the direction of the flow, and we aimed toward the ones with the most vigorous wakes. Occasionally we could hear waves beating the shore, and we steered more seaward. The grumble of a distant lobster boat reached us, but we saw only the gunmetal surface of the sea beneath the fog. After an hour, pushed by the 3-knot current, we arrived at West Quoddy Head.

The lighthouse there sits on the easternmost point of the United States; it is painted in horizontal red and white stripes, but without the red it would have invisible through the fog.

The hidden sun infused the fog with a pale, amber glow as we followed bearings from the lighthouse northwest into Quoddy Channel and then struggled against the ebbing current in Lubec Narrows, the 300-yard-wide gap between the Maine mainland and Canada’s Campobello Island. I’d powered past the breakwater, but Rebecca went to the Canadian side to ride an eddy and hugged the shore until the current lessened, and we met at an island up-current. Surrounded by fog, we searched out eddies to help us on our way.

Shackford Head was a shoreline of dark cliffs that we kept close by to avoid the standing waves just offshore. I’d hoped then we’d be able to see Sumac Island, where we’d camp, but the fog was still too thick. I would need to dig another chart out of my day hatch to get a bearing. It was only a mile away. We drifted for a moment, sipping water, and then, just like that, the fog lifted. One moment we looked out into a dense wall of it, the next we easily identified the small island where we would camp.

I put my water bottle away and took a bearing off the deck compass, in case the fog returned, and we dug in for one last stretch– our 34th mile for the day.

Sumac Island has about as much area as a two-car garage, with barely room for our tent amid the trees and fragile vegetation, but it would be home for a needed rest day. In the morning, we lingered in the tent, listening to drips of condensed fog falling from the trees and tapping on the fly. I opened the vestibule and gazed out at the miniature terrarium world of the forest floor, the princess pine and British soldier lichens, and plush, bright mosses. Beyond that was dense fog. I crawled outside and stretched.

After two nights on Sumac Island in Cobscook Bay, we went into Eastport, hoping to continue across to Deer Island, in Canada. Unfortunately, the customs office there had closed—but we were happy enough to return for a third night on Sumac, before turning around for the last leg of our trip.

With the tide out, Sumac Island stood like a small mountain of dark, angular rock, draped with rockweed. Atop it lay about 4′ of black, loamy soil, held in place by roots; in its interior is a secret garden thick with delicate, ankle-high flowers and greenery sprouting from the pine-needle duff. We tiptoed carefully around it, stepping only on logs and rocks.

I climbed into the hammock with my coffee. A metal skiff motored past, then pulled up onto the ledges. The skipper stepped ashore and wandered among the seaweedy boulders, bent over at the waist, collecting periwinkles. A beat-up aluminum canoe arrived next, with a man sitting in the stern steering with a small outboard motor. Black handles of clam baskets arched above the gunwales. It was Sunday morning. The fog gradually thinned, revealing houses and low, rolling pastures on shore. Later, we paddled the 3 miles to Eastport, where we spent the day replenishing supplies.

The next morning we paddled into a thick wall of fog at Shackford Head and caught the ebb that carried us back beneath the Roosevelt International Bridge in Lubec, where the din of the rushing current echoed through the quiet town. We let the tide take us past West Quoddy Head Lighthouse, and out into Grand Manan Channel. The land soon disappeared behind us in the fog. Heading back down the coast, we’d begun the last leg of our trip.

Miles from an invisible shore, we watched the water surface for clues, looking for the strongest current to push us back down the Bold Coast. But we had different ideas about which way we should go. I favored the magnetic bearing that roughly paralleled a route south along the coast. Rebecca, wanting as much help as possible from the current, veered seaward, paddling away from me until she nearly disappeared into the whiteness. With more than 30 miles to paddle that day, we needed help from the current, but I worried about getting too far out to sea. Still, with my wife about to disappear altogether, I abandoned my bearing and followed her. Together we watched for lobster buoys, the only indicators of the speed and direction of the current, and every now and then we’d hear the muffled thunder of surf and adjust course to paddle farther offshore. A lone puffin found us and circled overhead a while before flying off into the fog.

Rebecca paused and cocked her head. “Hear that?” I couldn’t, but she described the hooting of the whistle buoy off of Baileys Mistake, a 3/4-mile-wide bay on the mainland. A mile off maybe? Two? Again, we adjusted our heading offshore and we encountered great floating rafts of rockweed and other surf wrack, and guessed that it had drifted out of Baileys Mistake. After a while, we paddled into another patch of debris, and it made sense that it had probably floated out of Moose Cove. The current had slowed though, and we soon found lobster buoys bobbing over slack tethers. We’d paddled into Grand Manan Channel nearly three hours earlier, and now the tide was changing direction. We took a bearing toward shore.

Ram Island in Machias Bay feels far more remote than it is, only 1-1/4 miles off the nearest mainland point. Now owned by Maine Coast Heritage Trust, the island’s vegetation is kept in check by a pair of semi-wild sheep. In the distance to the east, Libby Island Light is one of the foggiest in Maine, and the site of numerous shipwrecks.

We camped again on Cross Island, our second night gazing across the channel at the slow pulse of red lights marking the grid of the Navy’s radio towers, and in the morning, foraged blueberries in the meadows around the old lifesaving station. Any island we camped on for more than a night became a favorite, hard to leave, but we finally set-out, across Machias Bay and into Little Kennebec Bay, borne inland on a bumpy ribbon of quick current, finally following a narrowing maze of channels into a secluded tidal pond. Here we would spend another two nights, taking shelter from strong winds and seas, and visiting Dickinsons Reach, a now vacant community of remote wooden yurts built by simple-living guru Bill Coperthwaite and his like-minded friends.

The current carried us back out to sea, and we wove through the Roque Island archipelago on our way to Jonesport, where we again resupplied at the variety store and, as a downpour began, let the current buoy us down Moosabec Reach.

The next morning, on Sheep Island, we sat at the picnic table, gazing at the chart spread before us with rain pattering down on the dining fly over our heads. We were having our second round of coffee. Fog had been coming and going, sometimes enveloping us completely, but then drifting away to reveal the shore of Cape Split or the distant islands. But it was dry beneath the rain fly, and even a little warmer, and we had enough water to make hot drinks all day long.

It was Saturday morning, and we could see all of the probable moves to get us back home to Stonington by Thursday or Friday. We measured the distances on the chart with a string, guessing where we might paddle each day, and which campsites we might get to each evening. We stared at the chart. I wanted to finish what we’d set out to do, but I didn’t want the trip to be over.

“Well,” Rebecca said. “We can come back any time.”

“Sure.” But our schedule wasn’t the only thing that would change. The air already felt cool, as if autumn were upon us. This trip would soon be in the past. Maybe that’s why we were taking another zero day. We could have paddled in the fog and rain, but we liked the island; we even had a privy and a picnic table. Most of all though, we wanted to preserve this feeling of being in our own world and feeling at home in it. Over the last 50 days we’d fallen into a rhythm that doesn’t come on a weekend outing. And the feeling of home came easier when we had no home elsewhere.

Not much more than a ledge, Dry Island in Gouldsboro Bay was true to its name the night we were there, and remained dry, though I woke before high tide just to be sure. Legit camping options are scarce between Frenchman Bay and Petit Manan Point, so we took what we could get.

A group of paddlers in orange and yellow tandem kayaks came around the end of Sheep Porcupine Island, flying along downwind, some with their paddles held aloft to catch the breeze. The frontrunners came abreast of us, shouting like kids on a carnival ride.

Mammoth cruise ships lay at anchor off Bar Harbor, their shuttles zipping back and forth, and a couple of bloated motor yachts were parked in slips at the public dock.

Though Bar Harbor is known for its cruise ships and crowds of tourists, we could usually find a stretch of steep shoreline not far from town for ourselves, like this one along Long Porcupine Island.

We pulled the kayaks onto the sand and headed into town. Rebecca and I had lived outdoors for the summer, crouched on rocks while we cooked, and slept on the ground. My clothes were stiff and streaked white with salt; my tan tinted with grime. The sidewalks were filled with ambling tourists flowing in and out of restaurants, gazing into shop windows. When they caught sight of me, they quickly looked away.

I longed to get back on the water, and I dreaded the end of our trip.

We spent our last night on The Hub, a tiny island, lying out on the warm granite slabs, watching stars and satellites until we could no longer keep our eyes open

On the hottest day of the summer, we paddled across Blue Hill Bay and back into the orbit of Deer Isle, closing the loop that had taken us over 600 miles and nearly two months. As we approached our take-out at Stonington, the heat was replaced by a cool north wind and we paddled hard just to stay warm, as if the season had turned the corner in a single day. We lingered in our boats and pulled alongside each other. We were looking forward to showers at the campground, clean clothes, and a dinner at a restaurant in town, but we were in no hurry. We’d lost whatever sense of hurry we’d had at the beginning of the summer, but knew that would begin to change the moment we landed. We looked at each other. We were both salty, dirty and exhausted, a little gaunt around the cheekbones, but all that only made our smiles brighter.![]()

Michael and Rebecca Daugherty are back in Stonington operating a kayak guide service. Michael is the author of AMC’s Best Sea Kayaking in New England, and Rebecca has a studio and gallery. They paddle out to the islands as often as they can. A book-length version of this story, illustrated by Rebecca, will be available soon.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Wonderful, Michael and Rebecca. Cool to read the whole account.

Looking forward to the book.

Thanks for sharing your adventure. Hope the book is out soon.

Thanks for reading! Rebecca is creating block-print illustrations, and I think the book is almost done. Trying not to rush it. Every time I put it aside for a month and return to it, it seems to improve. Summer is keeping us busy, so it will probably be ready in the fall.

Dear Michael and Rebecca,

You anticipated the solitude of Covid in a magical way. So happy for you.

I liked your photographs and paintings very much.

Thank you.

Great story, and paintings by Rachel. Some of your paddling sounds like similar ventures I’ve had in the Pacific Northwest, especially along the west coast of Vancouver Island. One difference: most of our islands are not granite (though granite is the rule over in Desolation Sound, east of Vancouver Island). Whereas 25 years ago we saw few paddlers on the outside, in recent years it gets crowded sometimes. I blame the water taxis. You can camp on virtually any beach you can land on, though sometimes it’s pretty challenging above the tide line. And there are bears.

Rachel’s boat appears to be a Pygmy Coho. Do I guess right?

Thanks – and sorry it took me so long to see your comment. Some day we’ll venture out of Maine again, and I look forward to visiting the West Coast. I can’t say I mind the lack of bears along the Maine coast though. Yes, Rebecca was paddling a Pygmy Coho that she built.

I found the article a very good read. Good luck with your new book, and all the adventures that lie ahead. I myself have a 22′ sailboat, but also love to row, and kayak. I was born on the water, not literally, but around boats for my life. Now 65, still enjoying it. I sail ⛵️ on a lake in Upstate New York, a long ways from the ocean, where I truly long to be.

Goodbye and good luck, God bless!

What a wonderful story, particularly in the details that describe the magic of Maine, and in my opinion it’s unparalleled scenery on the East Coast. I’ve paddled in a few of the areas that were mentioned in the story and spend two weeks each summer sailing/paddling on Mount Desert Island. Summer in Maine is my “magic place”! Thanks for refreshing my memories.