I first saw designer Andrew Wolstenholme’s Coot dinghy at the Beale Park Boat Show around 10 years ago when his own Coot was being sailed on the lake by his daughter Jo. Somehow, that boat caught my eye among all the other traditional gaffers and luggers at the show.

I’d been looking for a design to build following the sale of my Iain Oughtred Whilly Tern, and had whittled my criteria down to something around 12′ that would be manageable on the beach, easily sailed singlehanded, and roomy enough for two or three when needed. And, of course, it had to be pretty.

Graham Neil

Graham NeilDesigner Wolstenholme describes the Coot as a Swallows and Amazons-style rowing and sailing dinghy. It should have a broad appeal beyond the fans of Arthur Ransome’s books.

I’m not sure why it caught my eye. Perhaps it was the cat rig with its high-peaked gaff, which, although common on the eastern seaboard of the USA, isn’t seen much in the U.K. Or it could have been that delicately elegant sheer that got my attention. Whatever it was, I was smitten.

Beale Park is the kind of boat show where it is possible to chat to designers, builders, and owners as you enjoy the atmosphere, so I took the opportunity to spend some time with Wolstenholme and get a closer look at his boat.

Colin Stroud

Colin StroudThe plans include an option for a high-peaked standing lug rig.

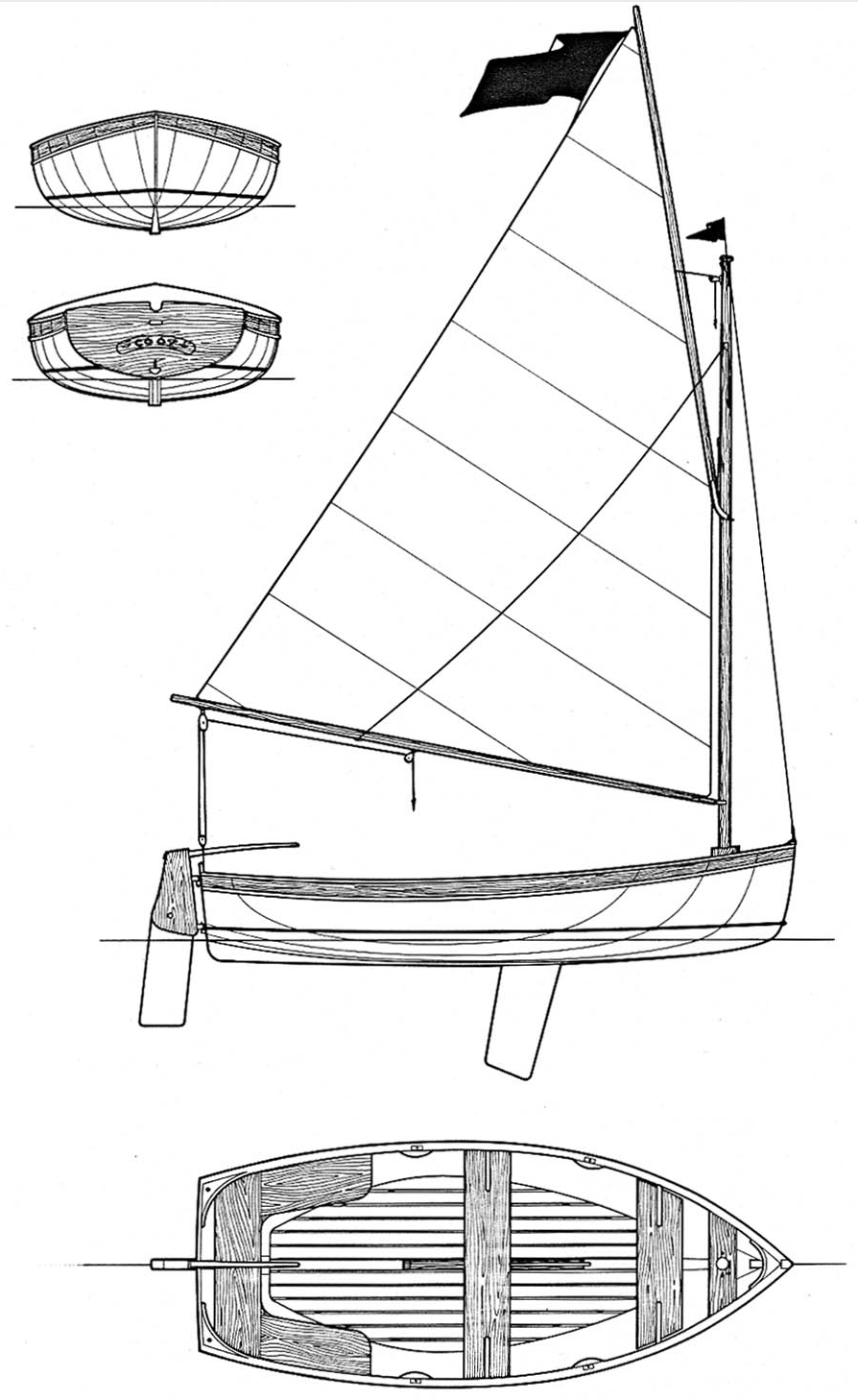

The Coot is 10′11 1/4″ in length with a beam of 4’7 1/4″ and carries a single high-peaked gaff sail of 70 sq ft (an optional lug rig is described in the plans). The pretty lapstrake hull has a traditional appearance with a near-vertical stem filling out amidships to firm, round bilges before tucking up to a sweet little transom. While many traditional dinghies of a similar size are almost indistinguishable from one another, there is something instantly identifiable about the Coot’s unique combination of hull and rig.

The interior arrangements are fairly conventional for a small, open boat. There is a central thwart for rowing solo, with a second rowing position on the forward thwart to help with trim when a passenger is sitting in the stern sheets. The mast is stepped well forward in a distinctive arched partner, leaving plenty of room on the forward thwart for an adult passenger or maybe a couple of children. Both the centerboard and rudder pivot for those times when the water gets a bit thin.

Andrew Wolstenholme

Andrew WolstenholmeThe arched mast partner provides a nice complement to the curve of the sheer.

The plans, which include full-sized patterns for the molds, are designed for boatbuilders with some experience: step-by-step instructions are not included. The Coot can be built with glued-lap plywood, strip planking, or cold-molding. For my preferred method of glued-lap plywood, the plank shapes aren’t given with the plans, so I would have to line off the planks myself, something which made me a bit nervous. With 10 planks per side there was a lot of scope for me to get things wrong. While I was considering the Coot, Wolstenholme was working with Alec Jordan of Jordan Boats to provide a CNC-kit of planks. I soon had a set of plans from Wolstenholme, and a kit of precut planks was on its way from Jordan.

Kelly Neu

Kelly NeuThe 10 pre-cut strakes of this kit-built Coot show the midsection’s rounded bilges.

The kit includes all the plywood parts for the hull, leaving it up to the builder to source the timber and fashion all the other parts to complete the boat. I chose locally grown Douglas-fir for the spars, transom, and keelson and experimented with sweet chestnut for the thwarts and gunwales. I’ve been very pleased with the results. The build took me about 18 months working in my spare time, and the boat was launched with the usual formalities on Barton Broad in Norfolk.

I tow the boat on a combi-trailer—a launch cart piggybacked on a road trailer— and can easily handle the 230-lb boat and 78-lb cart for launching and recovering. Getting the Coot rigged and ready to launch is a quick and straightforward operation. The mast drops through the partner and is held in position with a single forestay. With the boom’s gooseneck fixed to the mast, and the gaff jaws held in place by a parrel, the mainsail is ready to be raised with the throat and peak halyards pulled together. Clip on the mainsheet and the Coot’s ready to go.

Andrew Wolstenholme

Andrew WolstenholmeThe topping lift, seen here crossing the middle of the sail, is doubled and wraps around the boom and sail to serve as lazyjacks when the sail is dropped.

A very useful addition to the rig is the double topping lift, which keeps the boom up out of harm’s way while rowing and acts as a simple form of lazyjack to gather the sail and gaff when dropping them. All lines are brought back to the aft end of the centerboard within easy reach of the helmsman.

This little boat is very light and responsive, and will look after you while forgiving your indiscretions most of the time. The single 70-sq-ft gaff sail is easily handled and powerful enough to drive the hull at a good pace. The Coot goes to windward really well, is very well balanced with just the right amount of weather helm, and will punch its way through the chop with the occasional drenching of spray just to keep you awake.

It comes about in its own length, and I’ve never missed a tack. It’ll handle breezes up to Force 4 and 5 before needing to reduce sail. There are two sets of reefpoints, which I have set up for single-line reefing, and although Wolstenholme claimed he had never reefed his Coot, I can tell you that I have. Off the wind, especially on a dead run, there is the usual catboat’s tendency to roll, which can be a bit uncomfortable but easily tamed by sheeting in or tucking that reef in.

If there’s a need to heave-to for any reason—to take a picture, or have a bite to eat— I simply bring the bow into the wind, push the tiller over, release the mainsheet, and the Coot will sit quietly. Coming onto a beach or a dock, the boat can be slowed by releasing the peak halyard and scandalizing the main, or by dropping the sail into the double topping lift to make rowing easier.

Graham Neil

Graham NeilWhile this Coot has a single rowing station, the plans call for a second at the forward thwart for rowing with a passenger in the stern sheets.

I’m not much of a rower, but there will always be times when a little boat like this needs auxiliary power and it would be a shame to put an outboard on her. I’ve been told, by those who know these things, that a good pair of oars makes all the difference, so I have a pair of 7-footers, a nice compromise of length over stow-ability, always a problem in a small boat. I keep mine with the looms tucked up on either side of the mast where they can be quickly shipped when needed.

My first real experience of rowing any distance was when I joined my fellow boatbuilders in the UK-HBBR (Home Built Boat Raid) on their annual voyage down the River Thames. I thought I would be able to sail at least part of the way, but the weather gods had other plans, and I found myself rowing, loaded with camping gear, for the entire 70 miles of the five-day trip. So I can say with some authority that she is a handy little rowing boat, she tracks well, helped by her small skeg and her carry, which keeps her moving well past the recovery.

Andrew Wolstenholme

Andrew WolstenholmeThe floorboards provide comfortable, dry seating while sailing in light air.

I’m happy to say I arrived with barely a blister at our destination, the Beale Park Boat Show where the little boat took best in class in the amateur boat-building awards. The Coot is a proper little boat. With respect on your part it will look after you, take you on mini adventures on rivers, lakes, and estuaries, and be greatly admired wherever it goes.![]()

Graham Neil’s first boating adventures were as a 12-year-old boy in his native Scotland paddling a Percy Blandford-designed, canvas-on-frame canoe built by a friend’s father. Back then it was all woolen jumpers and Wellington boots, not a life jacket in sight. Later, in high school, he helped to build a 10’ stitch-and-glue rowing boat which still survives nearly 40 years later. Since those early days he has built several boats including an Iain Oughtred Whilly Tern, his Andrew Wolstenholme Coot, and KATIE BEARDIE, a sailing canoe designed together with friend Chris Waite. After a career in surveying and cartography, Graham is now retired and lives with his wife near Southampton, U.K., where he enjoys sailing his Coot dinghy in Chichester Harbour with the Dinghy Cruising Association and meeting other kindred spirits at UK Home Built Boat Rallies.

Coot Particulars

[table]

LOA/10′ 11″

LWL/10′ 9″

Beam/4′ 7″

Sail area/70 sq ft.

Weight with sailing rig/230 lbs

[/table]

Plans are available from Wolstenholme Yacht Design and kits are available from Jordan Boats in the U.K. and Hewes and Company in Maine.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

I have to have a chuckle. Every time I see a boat reviewed on this magazine the boats are always drifting around in next to no wind. Coming from Fremantle, Western Australia where it blows a tad I wonder if there is ever any wind in North America.

Well, Freemantle is in the “Roaring 40’s,” non? Here in the Middle Atlantic State of New Jersey (I live at the very southern tip) our winds are very benign, unless we are getting our usual winter/spring gales or summer/fall hurricanes. Sustained high winds for more than a day or two are very unusual and are well forecasted.

Yes there is wind here, we currently (2020) have him and his wife as President and First ‘Lady’.

Gostaria de saber o valor das plantas deste lindo veleiro e oque inclui a compra.

De que forma é apresentado e entregue o projeto.

[On-line translation: I would like to know the value of the plans of this beautiful sailboat and what is included in the purchase.

How is the project presented and delivered?]

Lovely; it looks a lot like the International 12′ Dinghy designed in 1913! Why doesn’t the Coot have knees under the mast thwart? The torsional forces are tremendous with a crew hiking out in a stronger wind. In the International 12′ Dinghy even those knees tend to break loose in the older boats, where the knees were smaller!

I have a newly built Penobscot 13 with a gunter-rigged main and jib. It looks similar to your Coot (except for the jib). I am intrigued with the lazy-jack arrangement you describe, since the P-13 needs to be rowed at times and what to do with the booms and sail is a problem, your solution looks simple and practical. I have studied your photos and the boat’s line drawing shown here. Is there anywhere I can learn more about rigging this topping-lift arrangement?

Thanks

Randy

I have a Penobscot 14 and I’d appreciate the lazy-jack rigging too!