During the turn of this century, Jon Persson, a boat designer based in Westbrook, Connecticut, wanted to create an open-water rowing craft that would be not only economical and simple to build but also accessible to someone new to the sport and yet still please those who were more experienced.

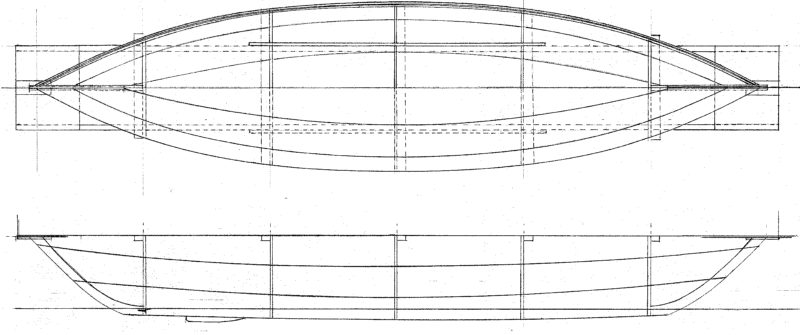

Persson began the design development with inspiration from the Francis Herreshoff–designed and John Gardner–drawn pulling boat the Green Machine, a beautiful lapstrake affair with dozens of steam-bent frames, and along the way incorporated aspects of the Chamberlain Gunning Dory. After several half models and prototypes, Persson finalized the design as the Atlantic 17 Dory—a symmetrical, double-ended, 17′-long boat that has a 48″ beam with the speed of the Green Machine, the seakeeping qualities of the Gunning Dory, and a very simple plywood-on-frame construction process.

I recently ordered Jon’s plans. They include profile and plan drawings, full-sized frame and stem patterns, and four pages of written instructions, which include a technique that ensures fair planking. The hull has two strakes, a flat dory-like bottom, and a small skeg. Construction is straightforward and detailed in the plans, and is within easy reach of an amateur who has some previous woodworking and epoxy skills.

Christophe Matson

Christophe MatsonThe flotation compartments in the ends are not included in the plans but are an easy modification to make when their bulkheads are combined with the frames.

The dory requires four sheets of 6mm okoume plywood for the planking and one sheet of 18mm meranti for the frames. The hull is constructed upside down on a strongback using its five frames as molds. On each side, three battens—a chine, a seam batten where the two planks meet edgewise, and an inwale—span from stem to stem. The seam battens need to be beveled to accommodate the plank joints. The joining of the battens to the stems without twisting the stems out of vertical is the most technical aspect of the build. The frames do not need to be beveled; gaps are backfilled with thickened epoxy.

The oversized plank blanks are plotted onto the plywood from scaled plans and then trimmed to fit on the boat. The plank sections are joined with butt straps which, used in combination with the batten construction, allows the planks to be clamped and glued onto the boat in an unhurried process—one piece at a time—without wrestling with full-length planks. If care has been taken in trimming the planks neatly to the seam batten, only a little detail work should be needed to fill the joints between the garboards and sheerstrake with thickened epoxy. The planked hull is ultimately ’glassed on the exterior with 6-oz cloth.

Christophe Matson

Christophe MatsonThe parallel risers allow for easy adjustment of the slip thwart. The two sets of combs for the stretcher accommodate the switch from rowing alone to rowing with a passenger.

The thwarts are laid out on two straight and parallel seat risers that are supported by the three center frames. The thwarts are not permanently secured to the boat and can be moved anywhere on the risers to accommodate any rower’s size and preferred distance to the oarlocks. The thwarts are specified at 10″ wide, but I made mine 8″ since they are infinitely adjustable. Also, the risers extend past the two #2 frames by 6″, which allows for a passenger to place an 8″ thwart as far aft as possible and face forward with additional space for legs. A wider thwart would be cantilevered beyond the risers and could invite an unwanted backward spill.

The only items not fully described in the plans are the oarlock pads to accept the sockets. In every Atlantic 17 I have seen there is a different solution, from neat little pads that don’t add any height to the gunwale, and nylon blocks with multiple sockets that allow for fine adjustments to the trim of the boat, to large pads that extend out from the gunwale. Since I am over 6′2″ tall, I decided to pad the solo position and forward position straight up by 1-3/8″ from the gunwale to help the looms clear my knees. I left the aft socket at gunwale height for my wife, who is shorter, to row from this position.

My boat, including the buoyancy tanks fore and aft that are not in Persson’s plans, came to 106 lbs. Even with the extra weight, the boat is effortless to trailer, hand-carry by two, or trolley from trailer to water. I even entertained ideas of cartopping but found the 17′ length to be a bit unwieldy, though a longer car with a wider roof rack and a second strong person could make this more feasible.

Allison Grappone

Allison GrapponeThe author, here at the oars, has been able to push the Atlantic 17 to a speed just over 5 knots.

The boat, with its narrow bottom, is initially tender when stepping aboard or standing up, but once the rowers are settled on the thwarts, the boat becomes stable and predictable. The wide garboard acts as a hard stop when the boat is heeled and provides enormous secondary stability. I swim off this boat and can climb back in amidships with ease with only a few cups of water slipping over the gunwale during the maneuver. The high stability is also appreciated when rowing broadside to rollers.

The foot stretchers for the solo and forward position are adjustable and drop into notched ladders that are glued to the inside of the thwart risers. The aft rowing position, per the plans, places the foot-stretcher set into a notched spine that is glued to the bottom of the boat. I decided this 16″ x 5″ spine would take up room for camping equipment and left it out of my boat. Some Atlantic 17 boats have employed other methods to add a less obtrusive foot-stretcher system, such as cleats glued to the inside of the garboards which accept a board slid between them.

Rowed solo the boat pulls and accelerates quickly. Oar length is not specified in the plans, but I use 8′ spoons for the center and forward positions. A second rower in the aft station could use the same length or 7′ 10″, depending on preference. A friend with another Atlantic 17 uses 8′ 6″ oars at the solo position with much success. Once the boat is up to speed, it carries almost two boat lengths after the last stroke before slowing down. Using my GPS, I found that a gentle sightseeing pace gets 3.5 knots, pulling harder (but still at a long-term sustainable amount) achieves 4 knots, and pulling all-out I indicate slightly over 5 knots. Add a second rower and the speeds at the same efforts conservatively increase by half a knot.

If the boat is appropriately balanced, the base of the stem should be sufficiently buried and the bottom does not slap. For such a light boat with a flat bottom and rocker, the boat tracks fabulously in a crosswind and does not exhibit much weathercocking as long as the rowers are correctly positioned. Someone along for the ride in the far aft passenger position can exert some weathercocking effect.

Allison Grappone

Allison GrapponeThe dory handles waves with ease, holding its heading and its speed.

I recently went for a row in Casco Bay, Maine, during a blustery day with sustained southerly winds of 15 to 20 knots and higher gusts. The harbor opened to the southeast and was filled with short rollers and some windblown crests. The fine bow struck a clean path through the waves, and the boat rode nimbly up and over the crests. On the descent into the face of the next wave the flaring sheerstrake diverted the water and kept the interior of the boat dry. Unlike a heavier, traditionally built dory, the Atlantic 17 won’t punch through waves carrying its momentum; instead, it rides lightly on the surface. Without the extra mass a little more work needs to be expended to keep her going against both wind and wave, but quicker acceleration and lack of spray is paid in return.

Allison Grappone

Allison GrapponeThe fine ends let the dory make a smooth passage through the water, leaving very little disturbance in its wake.

When I row downwind, surfing the rollers, the bow does not aimlessly veer but maintains solid directional integrity, an attribute that is much appreciated in an open-water boat. However solid its own tracking, the Atlantic 17 is also easily turned. At full speed on flat water, I can turn it 90 degrees from its course with three solid strokes on one side. At rest, the boat easily spins in the footprint of its own length.

This beautiful, sleek boat fulfills the requirements of a simple and economical build, with easy handling and safety for beginner rowers and speed for experienced ones. It makes a great day/picnic boat for two, and an efficient and safe camping vessel for one. The Atlantic 17 is a fine introduction to the joy of open-water rowing and has quickly become my most frequently used boat.![]()

Christophe Matson lives in New Hampshire. At a very young age he disobeyed his father and rowed the neighbor’s Dyer Dhow across the Connecticut River to the strange new lands on the other side. Ever since, he has been hooked on the idea that a small boat offers the most freedom.

Atlantic 17 Particulars

Length/17′

Beam/48″

Depth amidships/15″

Plans for the Atlantic 17 are available, in printed form only, from Jon Persson Designs for $60 plus shipping.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Comments:

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.

Great looking and seaworthy craft!

What a very good-looking little boat! Just for the looks I would have made the top of

buoyancy tanks parallel to the gunwale.

In a paraphrase to Herreshoff I would say: “Simplicity and small boats are a guarantee

of happiness.”

Jelle de Waard, builder of a 17′ Oughtred Ness boat 20 years ago

the Netherlands

Very nicely sorted out. I like the adjustability to fit lots of folks, usually a problem in these little boats. Look forward to giving it a pull.

Maybe because I’m looking kayaking the Maine Island Trail, I ponder this boat being set for only one rower with large watertight gear lockers fore & aft as a camp cruiser. An alternative, at more weight & complexity (and likely beyond my skill to build), would be fitted lockers that can be removed when not cruising as opposed to multiple dry bags.

Yes, John! I cruise extensively along the MIT in my sail & oar boats and I built the A17 with the idea of using her along the trail as well.

I think she would make a very fine MIT boat. Her flat bottom is amenable to dragging across mud flats and the light weight helps when pulling her up above the tideline. The relatively dry ride would be appreciated as well. I would definitely “pick my weather” to get around some of the heads or big crossings, as she is still a lighter boat. Your bigger tanks idea is a good one. My small tanks keep her gunwales just barely above the water when she is swamped and I can shake her out canoe-style, but more flotation would be something I would consider for heavier cruising. Her attribute is her light weight, so if you go this route, try to use 4mm or 6mm okoume ply and western red cedar for interior framing. By using small ply gussets at the joints of the timber you can increase strength of the structure and keep it minimalist.

There are so many great rowboats that have been featured in this publication that I would use to explore the trail. Every one has different benefits for the discerning cruiser, but the Atlantic 17 is definitely on the list.

Thanks!

I would love to have one! If anybody would care to trade…I have a Stonington pulling boat (fiberglass, sorry); I would trade. She has a sliding seat, oar outriggers, and I get yelled at in the harbor for going too fast.

Hi,

Fantastic job on this great design! I have the plans and have been trying to determine how to cut the frames accurately!?? How do you do that ? Any help is appreciated!

Thanks,

Jerry

Hi Jerry,

Take your time and be careful! As the boat is symmetrical, it is important to get all the frames matched to each other.

There are a few ways to go about this, I’ll describe the dependable take-your-time way, and then I’ll briefly describe how I did it in my quick-and-dirty style.

I’m assuming you have laid out the full-size patterns on the plywood sheet and traced them out. Placing small trim nails at the corners through the paper you would then connect the dots on the ply after removal of the pattern. Jon Persson suggests using French curves for the curved sections, but I eyeballed it with the help of a few compass swings and a confident freehand since they are interior curves that don’t affect hull shape. Since frames 1 & 5 and 2 & 4 are identical cut out one master frame of each and then trace out its twin, which should match the original. No sense in re-inventing each frame. When two matching frames are finished, line them up together and clean up any disparities between them.

I used a scroll saw on my jigsaw and moved slowly, cutting slightly outside the line and then rasped to the line. Take care that the cut remains vertical and if not, rasp to fix. The frames are not beveled to the curve of the hull, Persson indicates that the boatbuilder backfills the gap between the frame and the hull with thickened epoxy, which simplifies frame shaping.

Now for my loud and dirty backyard technique: I cut out half of each frame using the above method and made sure it was perfect. Then I clamped that finished half onto the plywood stock for the twin and used a router with a flush trim bit to cut the first half of the second frame. That done, I flipped the master pattern onto the other side of the twin, and repeated. Now that the twin was complete, I laid the twin on top of the unfinished half of the master frame and cut that out using the twin as the pattern. This created identical frames which all originated from the first half. The method creates a lot of dust, so wear your respirator. If you are not familiar or comfortable using a router in this fashion, I would suggest taking your time with a scroll saw or jig saw. Obviously, this method doesn’t work with frame #3 which has no twin.

Good luck with your build. Take your time, do research online or in books, and wear your safety gear. It’s not a race to finish the boat, a bit of time invested in careful building today will be returned to you tenfold in an eye-pleasing boat that will happily serve you for decades.

Thanks, Christophe! For the tip on cutting the half-frame pattern, I can see using 1/4″ ply for the half-frame pattern and routing will produce a very accurate frame. Your boat looks great! Thanks for the info.