Nearly all wooden boat enthusiasts and amateur builders know of an Iain Oughtred boat. The Australian-born designer and builder developed his 7′10″ Acorn as a dinghy for oar and sail and expanded on the popular design to create its now most popular 11′8″ and 13′ versions. This family of lapstrake skiffs draws inspiration from the famous New York and Boston Whitehalls of the 19th century. They have sharp forefoot entries, slack ’midship bilges, and twisting garboards that finish on a heart-shaped transom. The Acorn 17, the longest of the versions, is a dreamy rowing instrument.

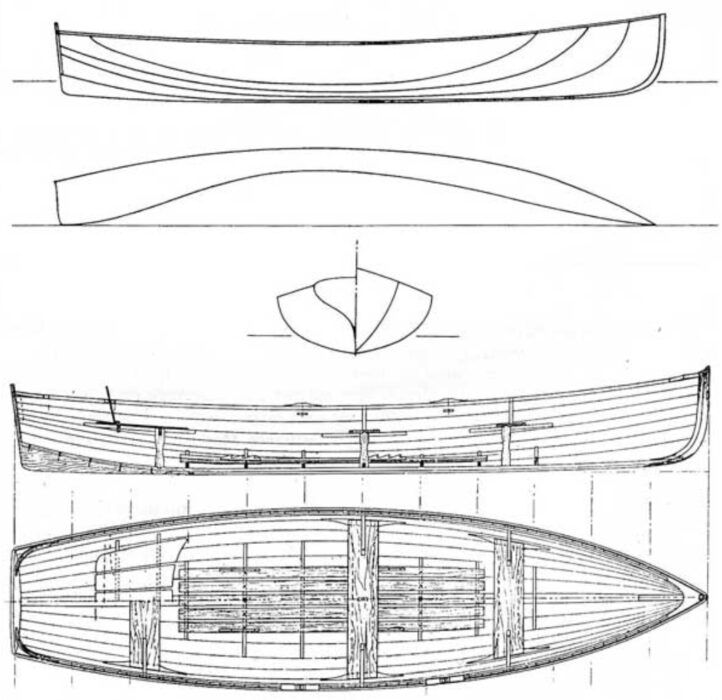

While kits are available for the Acorn 17, I built mine from plans. The 17’s plans are the same as those for the Acorn 15 but with the station spacing stretched 13.5 percent. The seven-sheet set includes lines, construction plan, rig, spar, and oar options, all to scale. Three of these sheets are full-sized drawings for the 11 station molds, the stems and knees, as well as the fore and aft transom faces to aid with proper beveling so no lofting is necessary to set up the jig. The instructions include a packet with a discussion on thwart layout suggestions, depending on the intended number of rowers and passengers. There is a handy materials and tools list included with a few paragraphs on construction notes.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorThe Acorn’s glued-plywood lapstrake hull gains strength from seven laminated floor timbers and laminated quarter knees and breasthook, and stiffness from a tapererd outwale and spacered inwale.

To build the 17, the builder simply increases the spacing of the 15’s station molds from 15″ to 17″. The stem and transom bevels can be cut according to the plans to start, then the inboard edges trimmed back until the bevels are flush with a fairing batten. Oughtred most often depicts the Acorn hulls to be glued lapstrake with 6mm marine plywood, seven strakes. The plans note that a traditional build—lapstrake plank-on-frame—would have 3⁄8″ planking with 5⁄8″ × 5⁄8″ frames at each half station, and that the hull could have eight strakes instead. The construction notes explain wood species options, depending on what is available to the builder. These planks, likely eastern white cedar here in Maine, would be copper-riveted to and between frames, and the laps should be bedded rather than glued. This traditional version would also add a full-length riser to support the thwarts, rather than the partial risers glued under the thwarts in the glued-lap plywood version.

The boat has seven laminated floor timbers that support a five-board sole. Additional structure is supplied by laminated quarter knees and a breasthook. The sheer is stiffened by a tapered outwale and a spacered inwale, as well as laminated thwart knees that make the curve to the gunwale but don’t fill in the angle between them and the thwart and planking. The plans show a two-piece stem, which can be beveled before assembling, a process easier than cutting a rabbet in a one-piece stem. Oughtred notes a traditional builder might opt for a single stem with a rabbet, though he states, and I agree, that the inner/outer stem system is best. The number of laminates needed to build the various parts suggests milling a nice pile at 3⁄32″, leaving them rough-sawn for better gluing.

Owing much to the Whitehalls that influenced its hull shape, the Acorn 17’s fine entry and deep skeg below a classic wineglass stern, provide excellent rowing capabilities with one or two rowers.

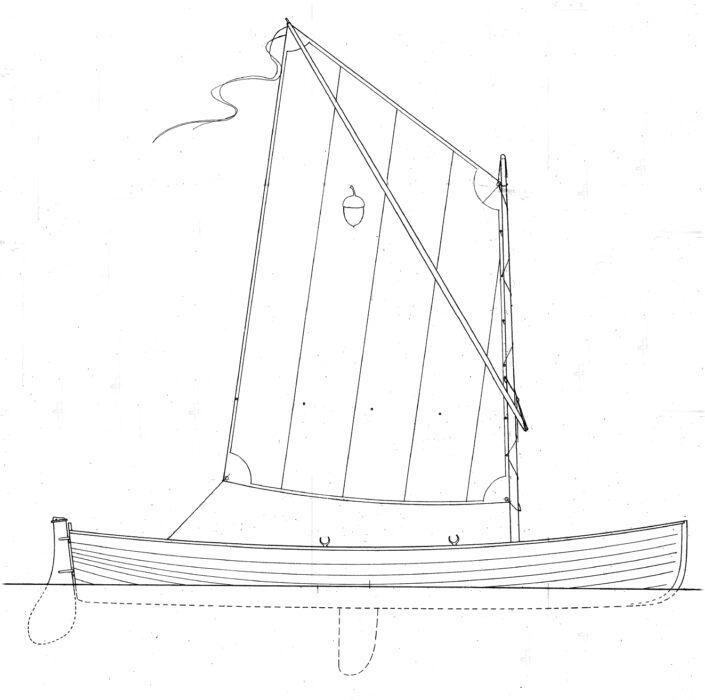

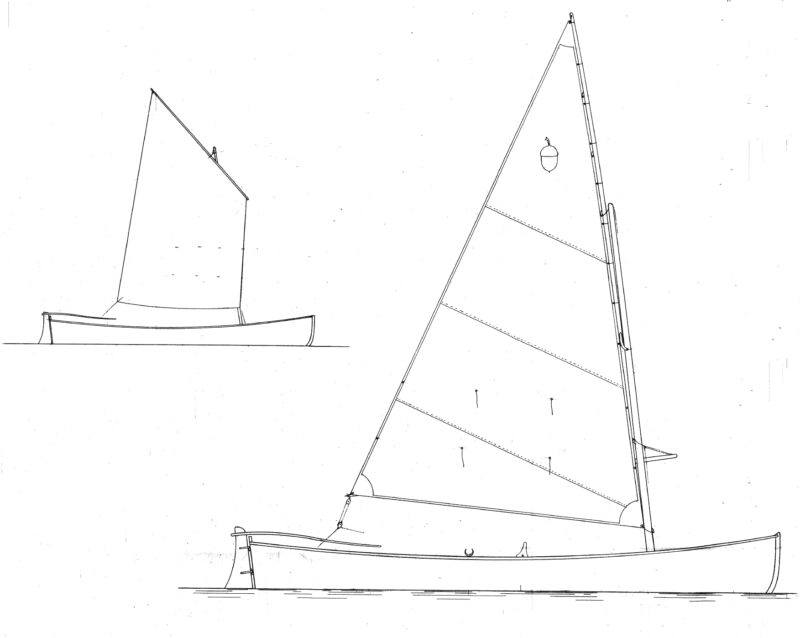

While the Acorn skiffs are primarily for rowing, Oughtred drew the sailing rig for the Acorn 15, and didn’t revise it for the 17. The standing-lug, spritsail, and gunter options each offer 60 sq ft of canvas. Spars are to be made of fir or spruce and the spar diameters are detailed along their lengths. Iain’s plans show a partner interrupting the forward thwart and the trunk landing between the sixth and seventh stations, through a widened keelson. The rudder and daggerboard are laid out on a grid to aid in scaling up the drawings to full-sized patterns.

The plans detail both flat- and spoon-blade oars with cross sections of the loom and blade. According to the plans, 8′ oars are best for the 15. The 17 is not specified but most oar length formulas go by the beam, thus with the same beam it’s safe to say 8′ will work.

The Acorn 17 is perfectly trimmed for a single rower sitting amdships using the aft rowing station. If joined by a passenger, the rower would move to the forward station to balance the passenger in the stern. The Acorn’s fine lines give her an efficient performance through the water, but being beamier than most rowing shells or canoes, she has good stability making her suitable for novice and experienced rowers alike.

Adjustable foot braces, included in the construction plans, are highly recommended. These are notched lengths of wood that capture a dowel stretcher, which allows the rower to choose a comfortable position for their feet. With solid wood thwarts, rowers of the bony-seat type may want a strap-down foam pad for long rows. While a drain plug is not indicated in the plans, I built my Acorn 17 with one under a sole for cleaning purposes and draining rainwater. The plans don’t indicate flotation either, but float bags could be considered to make the boat recoverable if capsized or swamped. I opted to add plywood bulkheads and decks forward and aft with watertight hatches to serve as dry storage as well as flotation. Fiberglassed garboards, sacrificial bilge runners, and brass half-rounds provide abrasion resistance underneath. A removable sliding seat, which Oughtred does not mention, is always up for discussion with a boat this size, to allow the rower’s legs to supplement the power of back and shoulders over a daylong trip.

Even built as light as possible, at 130 lbs this boat is not one to be carried on a roof rack; it is best trailered or docked. My compact SUV comfortably tows the 17 and its trailer. Getting aboard from a dock is somewhat like stepping into a typical canoe so it’s best for many to start from sitting on the dock. A rig would immediately solve this athletic move. Departing from a beach, the rower will get just their feet wet if the boat is parallel to shore. At rest ashore on its keel and bilge runners, it lists about 15 degrees.

The Acorn 17 can be built to sail, but if built solely for rowing, adding a stern deck gives it additional buoyancy in the event of a capsize or swamping. It also provides a backrest for a passenger on the aft thwart, as well as a location for a mooring cleat and a couple of fairleads for docking lines.

Stretching the 15 while the beam remains 46″ adds waterline length and yields a greater theoretical hull speed for the 17, which rarely disappoints. By the second stroke the rower can feel the boat’s consistent momentum through the water, even with a low stroke rate. The long keel has little rocker and when combined with the 6″-deep skeg, the Acorn 17 tracks nicely. Some effort is required to make sharp turns when gunkholing. As with most lightweight rowing skiffs that have shallow draft and high freeboard creating windage, a stiff wind can cause some leeway. The heavier traditional build, while not as handy for beaching or hand-hauling, may track better on windy days. In some significant chop, first time rowers will stay confident in the Acorn’s stability. Most are tempted during their row to stand up and stretch.

Ample space allows a singlehander to stow cruising gear evenly fore or aft of the ’midship rowing station. With a passenger aft, the rower takes the forward station to trim the waterline. When tandem rowing, everything should be stowed aft to avoid being bow heavy.

With two rowers and a passenger in the stern, the Acorn 17 glides along, tracking well, and maintaining momentum even if the rowers slacken the pace.

I built the Acorn 17 to serve as an attractive rowboat for use on the Maine Island Trail and similar recreational waterways. Overall, this longest of Oughtred’s Acorns is a delight and yields satisfying speed without the tender stability of some narrower pulling boats. It can provide excellent low-impact exercise opportunities for the solo rower, ample space for a comfortable picnic outing for two, and exciting performance with two at the oars.![]()

Elijah Davis is a boat and furniture builder in Maine.

Acorn 17 Particulars

Length: 16′ 7″

LWL: 16′ 4″

Beam: 3′ 11″

Weight: 135 lbs

Freeboard at oarlocks: 1′ 4″

Capacity: 2 persons + gear

Plans for the Acorn 17 are available from Oughtred Boats for AU$194 (AU$210 outside of Australia). In the U.S. Kits are available from Hewes & Co. for $2,368.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats readers would enjoy? Please email us.

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.