Art Arpin was a Flying Tiger. He wasn’t one of the original group of American aviators—he joined just after the departure of their commander, Claire Lee Chennault, in 1942—but took part in their ongoing mission to defend China against the Japanese. How do I know this? Because Art told me while he was holding one end of a board I was cutting for a boat I began building in 1998 and launched three years later. I cut a lot of boards, and Art told me a lot of stories.

First I have to tell how I came to build a boat in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. My wife, Samm, and I met as children growing up in the California Delta. I tell people our town was so small that we were the only people left who could legally marry. Samm is a remarkably understanding person, and when I asked her if she’d allow me to have my midlife crisis by building an Amesbury Skiff in the garage, she wholeheartedly agreed, as my other option involved gold neck chains and a Corvette.

The skiff, named ARCUS, cost $300 in materials and $400 in books to build. Now, 21 years later, I still use ARCUS on a weekly basis, and she looks brand-new.

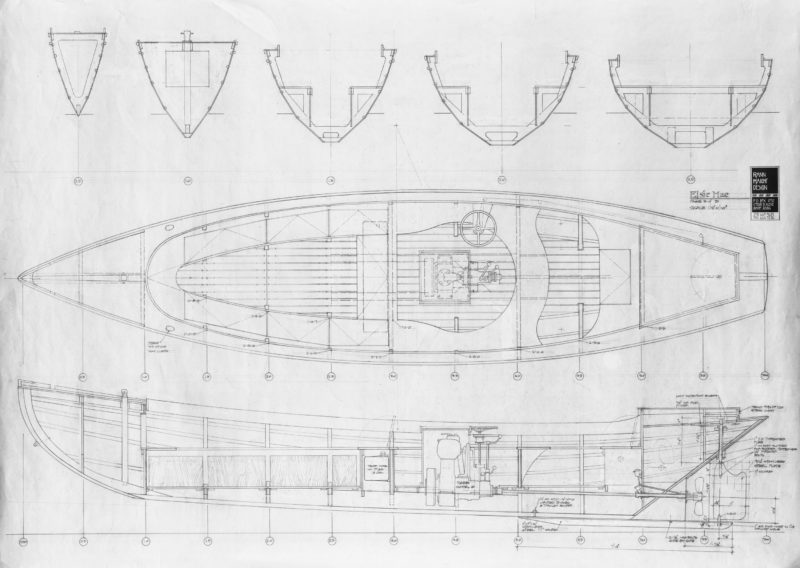

Drawing by the author

Drawing by the authorThere is no record of the original Hammond power dory’s interior so Rann was free to draw it as he wished.

Samm and I moved our family to Coeur d’Alene in 1995; being an architect, I designed and built a house for us on an island on the Spokane River. It quickly became apparent that we’d need a powerboat to enjoy the body of water that surrounded us. I dug out the books I’d purchased for the building of ARCUS and reread everything.

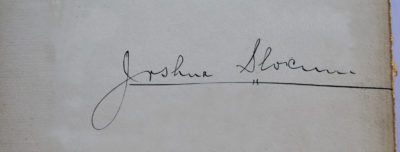

In John Gardner’s Building Classic Small Craft, Volume 2, I found a snippet of information about a mysterious half-hull model he found nailed above a workbench at the Hammond boatshop in Danversport, Massachusetts. John noted that the boat built from the model was known for its speed but nothing regarding the layout of the interior was ever found. He measured the half model and drafted the lines, and that drawing was the only illustration he included in his chapter about the Hammond dory. I thought it was the perfect boat. It was sleek and had the potential to be a great family boat. Best of all, no expert could tell me I was building it wrong. I named the boat-to-be ELSIE MAE after my mother.

Art was 83 years old; he and his wife, Audrey, lived next door. He had retired from the Seattle Police force, and the couple had moved in just a year before we arrived in Coeur d’Alene. In the summer, Art, wearing only a Speedo swimsuit, rode a bike all over the island. Once in a while I would see him in a rappelling harness on his roof, apparently just something he’d do when he got bored. Audrey, an elegant lady, seemed to expect Art to do something eccentric every day.

Rann Haight

Rann HaightArt Arpin, cleaning up excess epoxy with a power grinder, is the first person to get in the ELSIE MAE.

Although he was an odd character, his love of boats brought us together. He was impressed with ARCUS; I told him I intended to build a power dory after I finished the house. Having grown up in Connecticut, Art knew about power dories and offered to help me build mine.

I built our house with an unusually deep four-car garage. Its long wall— Sheetrocked, sanded smooth, and painted white—was like a giant sheet of paper. Samm hadn’t questioned why I had built such a long garage, but my reason became clear when I began lofting a 26′ power dory on the wall.

Rann Haight

Rann HaightElsie Mae meets ELSIE MAE: The builder’s mother pays a visit to the shop. The lofted lines adorn the long garage wall.

For those not familiar with power dories, they are a nearly extinct type of workboat that had their heyday at the dawn of the 20th century. They had narrow, flat bottoms and sides either flat or round. They were easy to build, could carry enormous payloads, and were popular with fishermen because of their seakeeping abilities. They never fought the water; they simply allowed waves to roll under them.

I began building the power dory when I was in my mid-40s. The project was relegated to weekends and nights: I turned on the garage lights after the kids’ homework was done and the dinner table was cleared. Art could see our garage window from his house and when the garage light came on, Art was soon knocking on the garage door.

I had generated a full set of drawings from lines published in Gardner’s book and lofted them on the garage wall. A single 24″-deep truss joist from the local lumberyard served as a strongback: I laid the joist on its side, leveled it, and marked the station locations. After that it was just a matter of cutting and fitting the plywood and lumber to do their respective jobs of keeping the water out.

Art had been an avid sailor in the Seattle area and had some experience with boat construction. He told me about restoring the ARTHUR FOSS, a wooden tug built in 1889 and now a floating museum on Seattle’s Lake Union. It was a huge project and he was proud that he’d helped save the old tug. He was quite helpful and always ready to place a clamp, support a board coming out from the tablesaw, or hold the dumb end of the measuring tape, all the while telling stories. He never interrupted the progress of the work—it was like having a book on CD playing in the background.

Art said he was a pilot during World War II. He loved flying and during the war had flown just about every type of aircraft, but mostly twin-boom P-38 Lightnings. I’m a big fan of World War II fighter aircraft and listened intently. Art flew in China and North Africa, and after the war he ferried brand-new P-51 Mustangs right from the factory to the bone pile in Arizona. He told me about an argument he’d had with the officer in charge of destroying the new planes. They were finished without radios, so Art would bring his own and install it before each flight. The destruction chief insisted that anything that arrived in the plane had to stay with it and be destroyed. Art said he had won the argument but didn’t offer any more details. He just smiled. His garage, I had noticed, was crammed with aviation gauges and electronics.

For weeks I measured and fitted pieces; Art always knew when to plug in a power tool I’d soon need and how to support the free end of a board I was working on. Our island community is tight, almost claustrophobic, and other neighbors often came by on weekends to chat and see the progress. No boat had been built in a long while on the island, so interest in the project was high and interruptions frequent. Art preferred to come around when there work was to be done.

He told me about working after the war at General Dynamics Electric Boat in Groton, Connecticut. He was the chief procurement officer for the USS NAUTILUS, the world’s first nuclear-powered submarine. Only Art and Admiral Rickover had complete access to the boat during its construction. Art didn’t know much about atomic energy, but he knew where to get a left-handed wing nut when one was needed. He would get the wish lists from the various foremen in the morning and go scour the docks until he had the material they needed.

Like me, Art was a displacement-hull enthusiast. While he had flown airplanes at 400 mph right at ground level and seen the world at high speed, water, he agreed, should be enjoyed slowly. But boats like the Hammond dory had slipped into obscurity early in the 20th century when aircraft development spawned engines with higher power-to-weight ratios. Boatbuilders, eager to take advantage of the new power plants, discovered the extra horsepower just pushed displacement hulls deeper into the water and wasted energy. The solution was to break the displacement barrier by climbing over the bow wave and riding on the surface of the water. New boats capable of doing this became known as hydroplanes, and with their seemingly limitless speed, the future of power dories was doomed.

Gardner’s book brought power dories back to life for me. His wonderful works preserved the old designs of the pre-hydroplane era. I devoured everything I could find from his pen and from Mystic Seaport.

After six weeks of work, the frames and bulkheads were assembled and standing at their stations on the strongback. I developed a system of half-round stringers following the chines as backing for the lapstrake joints. It somehow seemed to me the natural thing to do. Later I remembered it was exactly the same system used to make balsa airplane model fuselages, though this time I would be skinning over the stringers with plywood and epoxy instead of tissue paper and dope. To bevel the stringers to fit the angle between strakes, I mentioned to Art that I needed a long-tailed plane. Art left to look through his garage. He returned a half hour later with a plane over 2′ long. It worked perfectly.

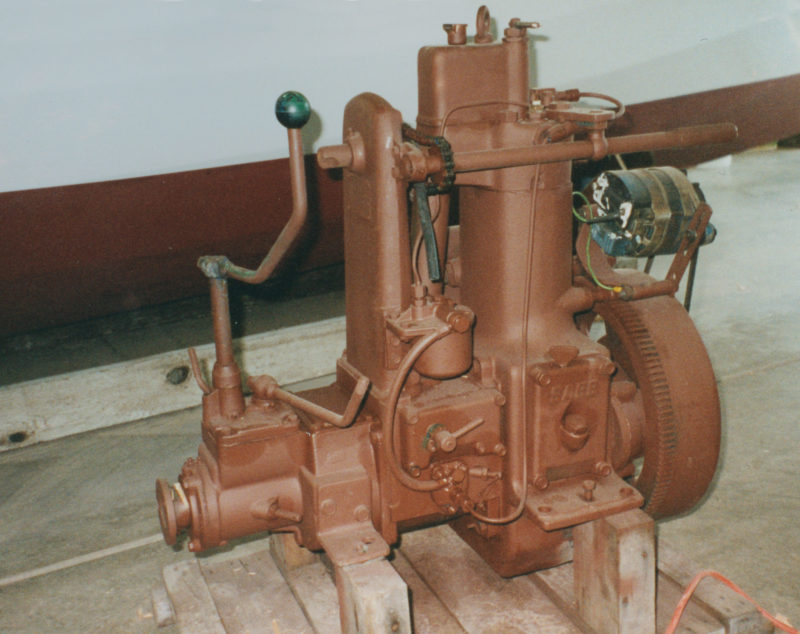

The dory was coming together without a hitch, but I still needed to find a power plant. The maximum hull speed would be about 5 knots and the dory would need only 6 hp to get there. I wanted the motor to be as close as I could get to what the Hammond brothers would have used, something heavy and low powered.

I had spent that first year of building the boat fretting over the problem of the gas engine. An authentic engine could be easily obtained from a supplier of make-and-break engines in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, but the volatility of gasoline haunted me. I asked the Canadian supplier how easy the old engines were to operate. I was assured that they were tough and reliable. I would need only to shut off the ignition, wait for the flywheel to slow, and then kick the flywheel with my foot in the opposite direction while reversing the ignition. This explains why old sea captains are always depicted with peg legs. I decided to look elsewhere.

Some Japanese companies were building small inboard diesel engines for sailboats. I considered one for a while, but the high rpms and knocking sounds of the engine seemed like a desecration of everything I was trying to do, and the engine would cost me around a thousand dollars per horsepower by the time I had installed the little shaker.

Out of frustration I called an old-time boat equipment supplier in Seattle and was given a lead to a waterfront repair shop in the Port of Everett. I called and, as instructed, asked for Jim. I explained my boat and said what I really wanted for it was an old Sabb diesel engine from Norway. Jim said he had pulled a 10-hp Sabb out of a sailboat just the previous month. It had been to the South Pacific twice but was in great condition.

Rann Haight

Rann HaightRann contemplated using a 10-horsepower four-stroke outboard in a well. “It would work beautifully and be very quiet, although extra ballast would be needed to get the hull down to waterline. I rejected the idea because I wanted the chugging and prop wash of a real old fashion one-lunger.”

I bought the engine over the phone, asking him to hold it until I could get over to Everett the following week. I called Art and he agreed to join me on the six-hour drive in my little pickup truck to see it. During the long drive, Art told me about his first night in China as a Flying Tiger. He was an honored overnight guest at the home of the village mayor and given a bed with an insect net draped over the bedposts—malaria was a problem in that part of China. Art awoke at midnight and saw an enormous tarantula on the inside of the netting. He drew his .45 and shot the spider dead center. Startled out of sleep by the gunshot, everyone in the house was in an uproar. The mayor rushed into the room and Art, through lots of hand gestures, indicated that he’d killed a dangerous spider. The mayor then explained through broken English that the spider was kept inside the net to eat any mosquito that should get by the first line of defense. I asked Art if he had to repair the ceiling. He chuckled and said it was a thatched roof.

When we arrived in Everett, I was pleased by what I saw: The heavy Sabb engine with its large flywheel would be a perfect fit for the dory. Jim accepted a down payment and agreed to hold the engine while I finished the boat.

I worked steadily throughout the winter of 1999. When it snowed, Art would arrive at the garage door in rubber boots. I set small goals for our evening sessions and let Art know what I wanted to accomplish before bedtime. Once the goal was reached, Art would say good night and head back home through the snow.

One Saturday, Art was helping while I mixed epoxy. I pumped a small amount of the two-part cocktail into the mixing cup and as I began the two-minutes of stirring, I asked Art if he had seen any action during the war. He said he had volunteered to fly as co-pilot in a C-47, a twin-engine transport airplane adapted from the Douglas DC-3. The mission was to fly supplies from US air bases in China, over the Himalayan Mountain range to the British in Burma along a route known as “The Hump.” They were over a Burmese jungle when a Japanese Zero pulled in behind the C-47. The pilot ordered the cargo to be shoved out the large side door to lighten the C-47. Art had the only weapon on board, a .45 automatic pistol. He opened the side window of the cockpit and fired at the Zero as it roared by. The C-47 pilot ordered the crew to strap in and put the plane into a steep dive aimed at the river in the bottom of a canyon beneath them. A fighter pilot, Art explained, can become fixated on the target and lose track of where he is. The pilot of the Zero followed the C-47 downward. Art’s pilot waited for the last possible moment to pull up hard out of the dive. The Zero, reacting a fraction of a second too late, couldn’t pull up in time and crashed into the river. The C-47 pilot was credited with a kill. Art finished the story by saying they landed safely but the plane never flew again. Its wings had bent up 5 degrees coming out of the dive.

Rann Haight

Rann HaightDaughters Erin and Sara, looking for work as game-show hostesses, present the recently righted hull. Planking is 3/8″ Douglas fir marine plywood sheathed in fiberglass and epoxy.

We flipped the hull upright on Mother’s Day. My parents were present and Mom sat in her namesake for pictures. In the weeks to come, all of our family members, whenever they were in town, helped with sanding the interior of the hull in preparation for epoxy and paint.

Haight family collection

Haight family collectionThe dory’s transom extends to the bottom; deadwood fixed to it supports the prop shaft. A stainless-steel skeg protects the rudder.

It had been almost a year since I’d put a down payment on the engine. I had been sending letters to Jim in Everett every month assuring him we would indeed collect the engine. Art and I drove over expecting the engine to be overhauled and a bill for repairs to be paid, but Jim said he had done nothing to the engine in the time he’d held it for me—there wasn’t anything that needed doing. The engine with its variable-pitch reversible prop ran still like new.

Drilling the hole for the drive shaft took a lot of courage, and Art and I discussed the process at length. He had, of course, an electric drill big enough for the job. I found a bit for the job, a 1½″ single-cutter auger with a pilot, and an extension and we started boring the 18″-long hole. The bit emerged right on the mark, and we celebrated with some ginger beer that Art found at an obscure market in town.

The interior was complete, and Amy, another one of our neighbors, was sewing the cushions and the boat cover. After almost two years working on the boat, I felt Art and I had gone through enough together to ask him if he had downed any enemy planes. I knew he had lost an engine in his P-38 and landed safely, and he had talked about losing friends flying in formation during difficult ocean crossings, but those had been due to navigational errors, not combat. He had never shared any stories about dogfights.

Haight family collection

Haight family collectionRann, Art, and Samm prepare to launch ELSIE MAE for the first time.

Art, who had always smiled while telling his tales, took on a grave expression. Toward the end of the war there was very little dogfighting. The Japanese aircraft and equipment were rapidly becoming obsolete, and their experienced pilots were all gone. His P-38 was not considered a fighter aircraft, so the tactic was to fly at a high altitude and make a single pass diving on unsuspecting Japanese planes. If you hit one, good; if not, you kept diving to get enough speed on so it couldn’t catch you. He told me he had downed two Japanese Zeros. Having lived into his 80s, Art realized how much life he had been able to live after the war. When he was flying in China he had not thought of the men in the planes, only that he had shot down machines. Now he realized how much joy he had deprived those young men of. We did not talk about the war much after that.

Haight family collection

Haight family collectionRann backs the ELSIE MAE from the ramp with his mother Elsie Mae and Art Arpin aboard. Rann’s daughter Heidi, aboard the skiff ARCUS with her fiancé Sean, records the moment.

We launched ELSIE MAE at the Coeur d’Alene Resort. I had just finished designing a house for Jerry Jaeger, one of the owners, and he lavished the event with a complimentary cruise-boat party. On board our friends celebrated with champagne; our daughter Sara played “Anchors Aweigh” on the violin (her music teacher’s idea); another daughter, Erin, made a wreath to drape over the bow; and oldest daughter, Heidi, and her fiancé Sean were aboard ARCUS video-recording the event While Art stood by, almost at attention, ever at the ready, I thanked everyone who helped on the project. He was, of course, aboard for of the maiden voyage standing amidships, his oar tossed upright in salute.

Haight family collection

Haight family collectionOn launch day, with Rann at the helm and his mother Elsie Mae in the sternsheets, Art proudly took his place amidships. The ensign is one Samm had made to reflect the boat’s origins, circa 1900. It has 45 stars.

I logged 790 hours of actual labor building ELSIE MAE. I spent at least twice that time thinking about what and how to perform each small step in the process. Art was there to be part of the resurrection of a boat from its long hibernation, and never suggested a better way to do something or argued over whether a decision of mine was wise or not. He spent at least 200 hours with me in the garage, and in all that time he only repeated one story. It has been 15 years since I built ELSIE MAE; Art Arpin is gone now, but he is as much a part of the boat as every piece of wood he touched.![]()

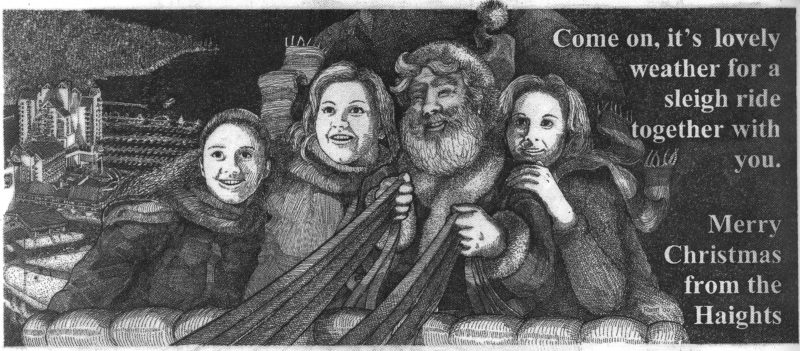

Born on a Northern California dairy farm in 1953, Rann began drawing in 1954. In his younger years, he worked as a cowboy, a pool cleaner and rock ‘n’ roll singer, but it was art and architecture that seemed to have the most promise for him. He was educated at Walt Disney’s California Institute of the Arts earning a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in Design. Rann is a licensed architect with projects in the western United States, Hawaii, Alaska, Canada and Mexico. Rann is married to his high-school sweetheart, Samm. They have three daughters, three sons-in-law, 6 grandchildren and 3 grand-dogs. They are all an inspiration to Rann’s art and spend a part of their lives posing for his 25 years of personal Christmas cards. To see some of his work, visit rannhaight.com.

Rann Haight

Rann HaightSara, Heidi, Samm, and Erin pose aboard the not-yet-finished ELSIE MAE for the year’s Christmas card.

Artwork by Rann Haight

Artwork by Rann HaightThe Haight’s Christmas card for the year 2000

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small wooden boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Great story. I really respect Rann for bringing an almost-forgotten design back and powering it with such an appropriate engine. Nicely done!

Small Boats Monthly could feature a dozen of this class of boat and its build every month and I’d never tire or lose interest. Thank you for the fine, well written article, the boat, the vision and your great publication. Power to traditional power boats!

Kevin Morin

Kenai, AK

Wonderful story indeed. Great mag please keep up the hard work!

Wonderful story. Are there any such boats around, but maybe 18′ to 20′? 26′ would be a little too big. Are there plans, kits, or a boat for sale?

Thanks for a great story. It brought tears to my eyes reading about a veteran helping a friend build a classic boat. Beautiful boat and story. Thank you for sharing!

Such a great story. I’m just starting my first project a 16′ skiff. It’s the people that make this story great. And what a place to build it! It was nice to read a story about a neighbor: My family and I live north of you just past Spirit Lake. I will keep my eyes open for your boat when we’re down on Lake Coeur d’Alene.

I thoroughly enjoyed the Hammond dory article. I have a 23′ Lunenburg dory with a 10hp outboard in a well in Camden, Maine. I always love to talk dories.