The story of the ELSON PERRY dates back to the late 19th century when Elson Perry, a lighthouse keeper, boatbuilder, and fisherman living in the coastal community of Port Medway, Nova Scotia, built a boat—a 20′ workboat carrying a handful of spars. It is believed that he built this boat for his own use and kept it for the rest of his life. It appears that a descendant kept the boat until 1929, when it was hauled up out of the water one last time and stored in a fish shack. There it rested until the 1960s when the house and land that included the fish shack were sold to the writer Calvin Trillin. Trillin donated that old boat to the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, where it has been preserved to this day (See WB No. 163).

When the museum decided to build a boat to celebrate the millennium, they chose to build a new version of that old Port Medway boat. This new boat is the ELSON PERRY. She’s proven to be a very shapely and able craft built by the museum’s resident boatbuilder, Eamonn Doorly, and launched on Canada Day—July 1, 2000.

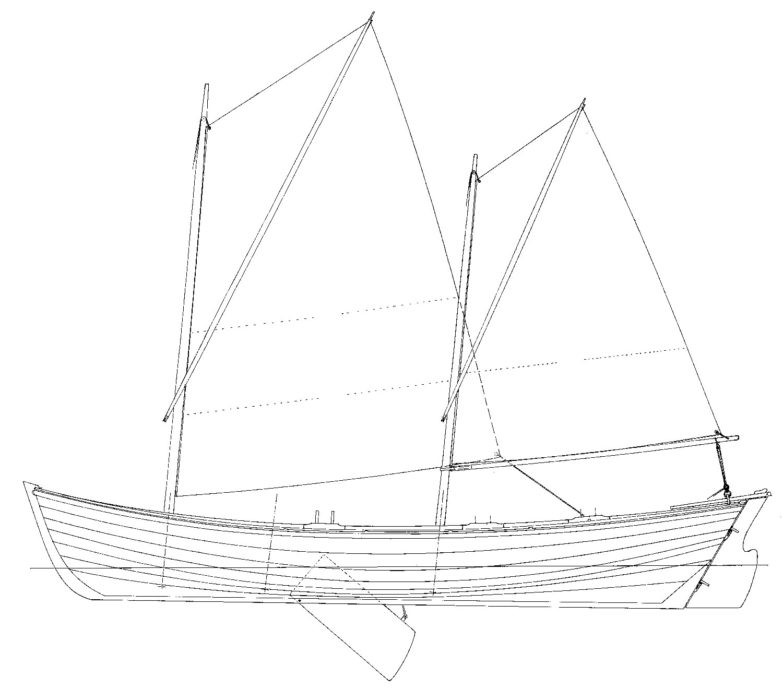

In the 19th-century Nova Scotia in which Perry lived, a fellow did any number of things to piece together a living, and in many ways Perry’s life and his Port Medway boat are reflective of that diversity. One of the unique mysteries of the boat is that there are three mast partners, one on each of the forward three thwarts, suggesting that she could be rigged in a variety of ways, perhaps for different uses. Sometimes the boat was used for hand-lining, other times for scallop raking, and with a boat so pretty I would hope that she sailed for the pure pleasure of it as well.

There are signs of influences from other boats in her design and construction, but the overriding truth is that she is unique and very much the product of one builder in one place and one time in history. Although Doorly was building a new boat, he was tethered to the history of that old Port Medway boat. The replica is proof that, although there have been many advances in design and construction in the past century, a simple well-thought-out and built boat is still a great pleasure to observe and use—and is every bit as capable today as it was when it was first built perhaps 140 years ago.

To state that Doorly was the builder is a little misleading; more accurately, one should say he was the lead builder, with every single employee of the museum contributing some of his or her time. The hours in the shop are now looked back on fondly, and with the boat in the water each summer in front of the museum, she is a source of pride for the staff.

Michael Higgins

Michael HigginsThe ELSON PERRY has mast partners at each of her three forward thwarts. The storage compartments under the thwart were not in the original boat.

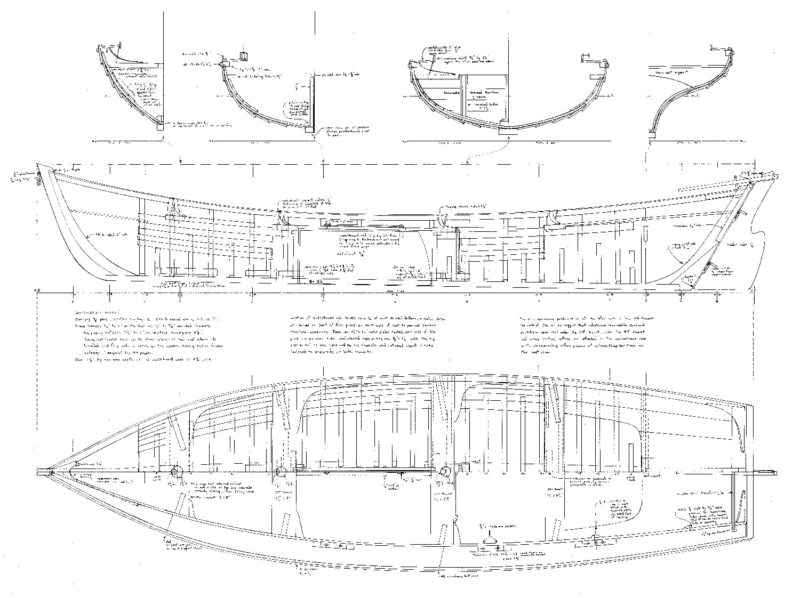

The boat was lofted from lines recorded from the original Port Medway boat by Ed Porter. This provided patterns for the stem, keel, and transom as well as for the building molds. These molds still exist and are in storage at the museum. All of these components were assembled right-side up and faired before the boat was planked. Like most lapstrake boats, she was planked—seven strakes a side—before frames were bent into the boat. There is a lot of shape in this hull, particularly aft. As a result, much care should be taken in lining-off the planking to ensure that one does not try to force too much shape into a single plank.

The stem and keel assembly is made of oak, as are the frames, and the planking is pine. No doubt another builder of this boat might choose other suitable woods available locally to them. Perry simply did what all good boatbuilders of that time did: He used woods readily available to him. Doorly did the same but was able to stray a little from his historical predecessor by using mahogany for the sheerstrake, which has added to the resilience and stiffness of this boat. The boat’s narrow side decks and long coaming also add greatly to her stiffness and aid considerably in keeping the ocean out. She has four thwarts supported by plenty of grown knees, and above the sole boards there is a partial ceiling—all adding up to a strong little ship.

The rig is full of traditional details, such as boom jaws and table. Much pleasure and pride will be found in splicing the standing and running rigging. No one piece of the ELSON PERRY is too big; this is a fully realized boat, but on a manageable size. There are ample opportunities to stitch leather on chafe points, and to fabricate your own vintage ironwork. The six spars would provide a chance for experimenting with different construction methods. A few could be solid, others laminated hollow with “bird’s-mouth joints” or tapered staves. For a builder with sailmaking skills or a desire to learn them, a suit of handmade sails would be just the thing to complete the project.

Michael Higgins

Michael HigginsThere are enough lines aboard to keep three people busy sailing the ELSON PERRY; four is better in windy weather.

This is not an instant boat; she will not be built in a few weekends over a winter, and she will require a depth of commitment. Few things are as disheartening as having an incomplete boat hanging around for years. On the other hand, if you have a suitable space, some basic tools, and perhaps 800 or 1,000 hours with which to work—not to mention several thousand dollars—you could build a boat that will turn heads and hearts wherever you may sail.

Now, I suspect that none of us is going to build an ELSON PERRY today for the inshore fishery or scalloping, so we need to think a little about what sort of sailing we are apt to do, and what sort of sailing the PERRY is up to. Port Medway is a sheltered body of water, and this being an unballasted, open boat, we would want to use her in coastal waters with an eye on the weather. But, that being said, she is an able and responsive boat, capable of impressive speed, particularly given the age of her design.

On a breezy day, the ELSON PERRY would sail best with a crew of four or so, not just because there are a lot of fun pieces of rope to pull on, but she could also use the weight to help keep her upright. She has plenty of power, and on a gusty and blustery day one needs to be agile to keep her leeward rail out of the drink. The reward is a very enjoyable ride indeed. Doorly reports, “Sailing the ELSON PERRY as a ketch is the most fun way to sail; she is very responsive, fast, and requires at least three people to sail, four in windier weather. Her purpose at the museum is to familiarize staff with the basics of sailing, so keeping staff busy and engaged while sailing is very important. I’ve tried other rigs on her, but she seems to come into her own when sailed as a ketch.”

Michael Higgins

Michael HigginsAt 20’ long, the ELSON PERRY is plenty big enough for camp-cruising, but also fast and lively enough for daysailing.

I can see us now deciding if we are going to be the Swallows or the Amazons. The ELSON PERRY is exactly the sort of boat that would appeal to Arthur Ransome. (Please, if you have not read Swallows and Amazons, do yourself a favor and find a nice old copy in a used bookstore, or get it new at The WoodenBoat Store, and settle in for a tale that will inspire you to build a boat and sail about your neck of the world with a renewed sense of wonderment and imagination.) If you would ike to explore a tidal estuary full of islands or inland lakes such as the Norfolk Broads in timeless style and grace, then the ELSON PERRY is a boat for you.

Endless days could be spent in pursuit of privateers, or on the run from custom agents with a contraband cargo of cheese, crackers, and cold lemonade. For fun, or to disguise your boat, you might leave the mizzen ashore, move the mainmast back a thwart to the next maststep, and rig her as a sloop. The mystery of the extra maststep will probably never be solved, but it would be very interesting to see how many different ways you could rig her. She is big enough at 20′ LOA and 5′ 5″ beam to carry the gear required for a weekend on the island, but small enough to trailer to another destination next week.

This is a timeless boat, and as such she is limited only by your imagination. She is at home along with her sister, the original Port Medway boat, at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic but would also fit right in at any gathering of wooden boats today. The ELSON PERRY is the boat in which we wish our grandparents had taught us to sail and row, and the boat in which we might teach our own children to sail and row.![]()

The Maritime Museum of the Atlantic no longer offers plans for the ELSON PERRY. The review appears here as archival material.

The ELSON PERRY carries six spars, making possible a variety of rigs. Ketch, cat ketch, sloop, and cutter rigs are all possible. These plans were drawn by Ed Porter and taken from the original boat owned by Elson Perry. The museum’s new version has a few modifications not shown here.

ELSON PERRY Particulars: LOA 20′, LWL 18’1″, Beam 5’5″, Draft 1’2″ board up 3’6″ board down, Sail area 210 sq ft

Any idea where plans might be located?

To suggest a solution to the mystery of the extra maststep it could be useful to look at Scandinavian boats. The Danish so-called “Tosmakke” have two spritsails. In heavy weather with steep seas and currents they have been sailed partially without reefs in the sails. Taking down one sail would mean an extreme change in lateral area, causing difficulties while tacking. To have a balanced boat again, one would take just one unreefed sail to the spare maststep near the center of the boat resulting in good maneuverability with small sail area.