Schuyler Horton

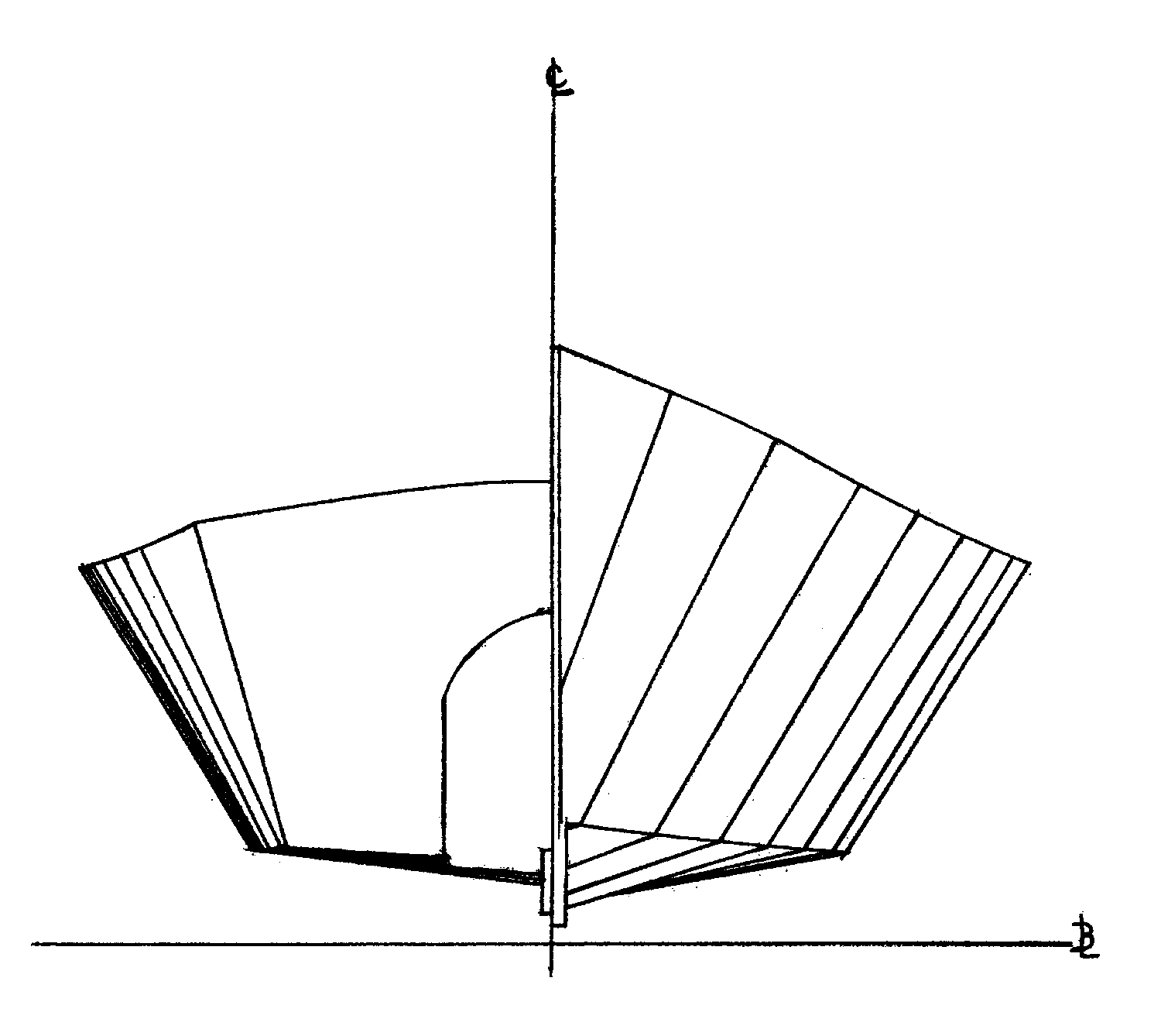

Schuyler HortonThe Simmons Sea Skiff was first developed as a beach-launched, oar-powered fishing boat for coastal North Carolina, and it eventually evolved into an outboard-powered range of sizes, from 18’ to 22’. The 18-footer above was built by its owner, for family fishing excursions on and near Narragansett Bay.

The Simmons Sea Skiff is the direct result of a North Carolina commercial fisherman’s need for a seaworthy skiff that would allow him to launch from the beach into the Atlantic surf, row through the waves, and fish with a seine before returning safely through the breakers. That first boat, built in 1946 by Tom Simmons, was a success, and eventually Simmons was asked to build larger, outboard-powered versions. Today, Simmons Sea Skiffs can be built in 18‘, 20‘, and 22‘ versions.

My introduction to the Simmons Sea Skiff was through a friend and neighbor, Schuyler Horton, who is fanatical about fishing. He goes everywhere with a concealed rod and tackle on the chance that a few spare minutes and a body of water come his way. Having fished every possible inch of coastline in Newport, Rhode Island, from shore, he was determined to get out on the water with his two young sons and introduce them to his passion for fishing. Without any prior boatbuilding experience, but armed with books and plans from The WoodenBoat Store, he built a Tom Hill–designed ultralight and then a Marc Pettingill Sweet Dream. Then he and his boys managed to chase down most of the bluefish that ventured into Newport Harbor. But he was still frustrated knowing that all of the fishermen in their Makos and Grady Whites fishing the rocks and reefs off Brenton Point had an advantage just beyond his reach. He needed to get out there. So he decided to build yet another, this time larger, boat.

He happened upon Ellis Rowe at the 2005 WoodenBoat Show in Newport. Rowe was displaying a new Simmons Sea Skiff 18 he had built, and Schuyler was immediately, well, hooked. The Simmons Sea Skiff is exactly what he wanted—something that can handle the chop off Brenton Point, especially when the sou’wester pipes up in the afternoon, and can be easily trailered. When not in use, it fits in his garage, and, most important, it’s substantial and safe enough to take kids out to the reef.

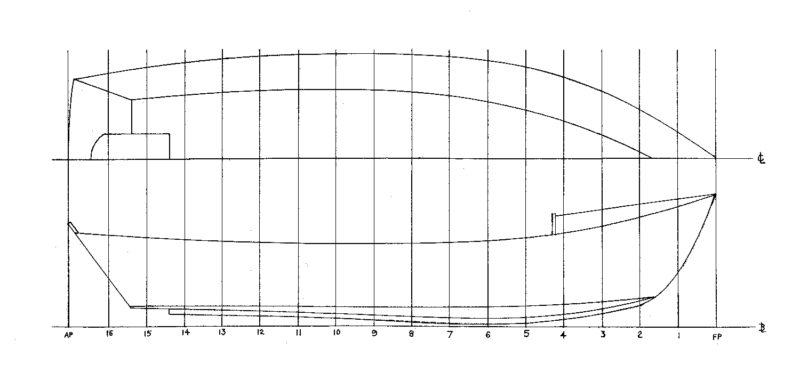

Tom Simmons’s first boat was inspired in part by a New England dory that had a very high bow. The fisherman who commissioned her also wanted a high transom to keep waves out as he surfed back onto the beach. The current plans, an excellent set drawn by the late David W. Carnell, a Cape Fear Museum volunteer who measured an original boat, retain those features. They boast jaunty and traditional lines that attract attention and flattering comments. The outboard motor is housed in a well that sits inboard, allowing the transom to remain higher than any comparably sized outboard-powered boat and serving to keep out breaking waves. A cutout in the transom allows the motor to be tilted out of the water, giving very handy access to the propeller in case a line or net becomes fouled. The bottoms all feature a slight, modified V-shape for a smoother ride.

Without an engine, the 18-footer weighs an impressively light 350 lbs. This presents a number of advantages: Fully loaded, with engine, it can be easily trailered behind most small cars; it can be beached and relaunched with confidence; and with a relatively narrow beam of about 5½‘ and draft of mere inches, it can even be rowed into tricky rock-strewn areas in pursuit of elusive fish with the engine up.

Schuyler Horton

Schuyler HortonEasy trailering and beachability, combined with reasonable seakeeping qualities, are the hallmarks of the 18’ Simmons Sea Skiff. Owners report that the boats become uncomfortable in seas over 2’, while the larger hulls can handle worse conditions.

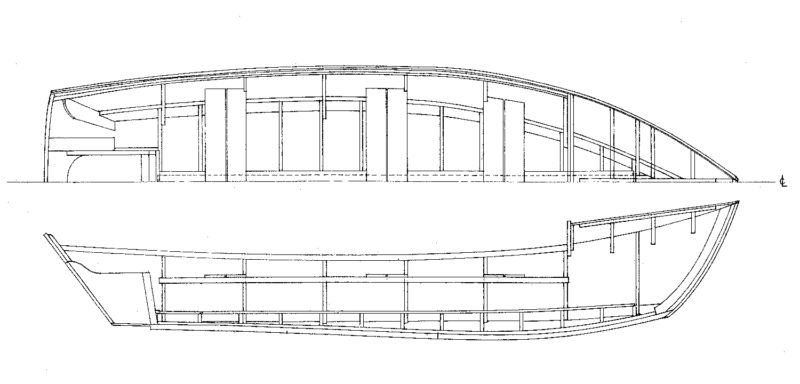

The construction of the Simmons Sea Skiff is straightforward and manageable for an amateur with some experience. One must keep in mind, however, that a Simmons Sea Skiff is a serious commitment of materials and time; it’s a whole different level of boatbuilding from plywood prams and kayaks. Good guidance is available, though. Before his untimely death a few years ago, Ellis Rowe published a series of articles in WoodenBoat magazine Nos. 186, 187, and 188 on the construction of an 18-footer.

Originally the boats were built of juniper (Atlantic white cedar) on mahogany, but as early as the 1950s Simmons began planking them in plywood. Building them in plywood today requires first erecting a strongback on which the boat will be built, making up a backbone consisting of stem (laminated or sawn), keel, floor timbers, transom, and motor well, as well as installing chines, planking the bottom and topsides, and then fiberglassing the bottom and motorwell. The plank laps are glued together and also fastened with copper rivets. The substantial frames are sawn from solid lumber, making a very robust hull.

As with most wooden boats, the fitout and finish are up to the owner. One thing that’s important to consider before the construction is what type of engine will be used, for its dimensions will determine how big the engine well and transom cutout need to be for the power plant to turn and tilt sufficiently. The number of configurations possible for the deck and interior layout are endless, and include a decked-over bow creating a storage compartment, a casting platform forward, an open boat with thwarts, center console, side console, and tiller steering.

Schuyler Horton

Schuyler HortonEarly Sea Skiffs were built of solid juniper on oak. Gluedlap plywood, as we see here, is also a good option.

Out on the water, the Simmons Sea Skiff does what she was designed to do, proudly charging into the slop upwind, fending it off downwind, delivering her crew to the fish. Because of her size, shape, and lightweight hull, she’s initially tender. Balance is always a consideration. Crew and gear weight must be distributed evenly to keep her level. It’s even possible to steer her left and right by simply moving one’s weight slightly from port to starboard. She has good capacity for gear and, as noted, the owner can decide how to best create custom storage solutions. At moderate speeds, winds, and sea states, she tracks well and handles chop from any direction. The lapstrake construction and considerable flare help to keep the spray down. When docking, launching, or hauling, her proud, high bow and relatively light weight can conspire against you and tend to get blown around—though this is more of a problem in the larger boats.

I didn’t handle Schuyler’s boat in rough conditions, but he tells me that when the seas are more than 3‘, he’s reminded quickly that he’s in a small boat. She gets wet and tossed around a bit. In conditions below that, she’s so well behaved that it’s possible to be deluded into a false sense of security. He doesn’t head outside of Narragansett Bay if it’s expected to blow more than 20—which is fine for him because there are plenty of places to fish within the bay.

Schuyler’s observations were reinforced by another friend, Mike Lavecchia, who also has an 18-footer out of York, Maine. He uses her mostly for exploring with friends and just getting out on the water, for which she’s perfect. He has taken her offshore down to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and back, and when he’s been caught out in winds over 25 knots, or seas in the 2‘–3‘ range, he too gets uncomfortable. He also reported, to little surprise, that when she’s loaded with five or six adults she struggles to plane. With 25 hp, the 18 will do about 20 knots with two people aboard. As for fuel consumption, both Schuyler and Mike described it to me in months, each saying they fill up their 3-gallon tanks once or twice a month during the boating season.

The 20- and 22-footers have better seakeeping abilities than the 18s. The labor to build the larger boats hardly differs from the smaller ones, but there is a cost difference in materials. Laying aside that cost, the trade-off comes down to this: Are you willing to sacrifice garage storage, and towing with the Subaru wagon, to be able to venture out in 4‘–6‘ seas?

The Simmons Sea Skiff is popular now, and although it is unknown how many have been built, Tom Simmons turned out an estimated 1,000 or more between 1946 and 1972. And the Cape Fear Museum reports having sold over 2,000 plans. It is safe to say there are plenty out there, and it seems an excellent choice for the home builder—for many reasons, including all of the support available from fellow builders. A few minutes on the Internet will also reveal numerous threads on the WoodenBoat Forum, as well as a website about the boats, an owners’ club, and countless photos.

When Schuyler Horton wanted to get out to the prime fishing grounds and didn’t have $40,000 to $50,000 to buy a new Grady White or Mako, he found a very economical alternative. He spent $11,000, and working mostly weekends, got out on the water 18 months later with his boys on a brand-new boat. At the time, the boys were six and nine years old. Today, they’re 12 and 15, and have been growing up learning about fishing and boat construction on a fine, seaworthy, home-built small boat.

For information and to order plans, contact Cape Fear Museum.

Cape Fear Museum

Cape Fear MuseumT.N. Simmons took much inspiration from the hulk of an old beach-launched dory when he developed the lines of his eponymous Sea Skiff. The 18-footer, whose lines are shown here, measures 11″ less than its nominal length. It has an optimal horsepower range of 25–40.

The flaring sides give it a high load-carrying capacity, while the scantlings yield a relatively

lightweight hull.

Cape Fear Museum

Cape Fear MuseumParticulars:

LOA 17’1″

Beam 5’7″

Draft (motor up) 5″

Weight (empty) 300 lbs

Power 25-30 hp

In the 70’s, I owned a Simmons. Same color; same layout; and two little boys. We fished, camped, and just messed around in the “big green boat”.

Good times…

We had one in the ’70s with a 40 hp Johnson and she was a beast.

I built an 18 footer about 15 years ago. Ending up with a 25hp motor.

I built an 18′ Simmons in the early ’90s. The directions that accompanied the plans from the Cape Fear Museum were detailed and all that I needed. The size difference between the 18′ and the 20′ is impressive. I think the 20′ is about double the volume and the weight.

I am restoring an 18 ft Simmons style boat. It has a fiberglass bottom with wood strakes. Almost ready for paint after repairing and rebuilding the cracked and damaged wood. Fiberglass over the butt splices and then the outside of the hull. In the water this fall!