"It all started as a pile of boards.” I wrote that in the third grade as the first sentence of a story about a small scow, all of 42″ long, that Dad and I built together when I was eight years old. It was as good a start as any, even now for this tale about the building of CURLEW, a 16′ Whitehall, and the history that an old, eccentric family in the hills of Mississippi has had with building wooden boats far from the sea.

CURLEW began as I was making the transition from teaching school to becoming a musician and caretaker for the family land here just north of Vicksburg, Mississippi. The large tract of land has been in the family since my great-great-grandfather, Benson Blake, settled here in the 1830s. Once a grand sweep of woods and farmland, it is much reduced, but six generations later, we Blakes are still here.

My desire to build a boat such as CURLEW would never have gotten anywhere if I had not had the good fortune to have my father, Daniel Blake, also living at the family place. He has built a string of wooden boats over the years, and it is never too difficult to talk him into another one. I started with several design requirements for my boat: It must be round-bottomed, trailerable, big enough for four adults, and it must sail. We pondered the classics and after much wrangling, we had settled on the 14’ New York Whitehall on page 197 of H.I. Chapelle’s American Small Sailing Craft, but it was a bit small and had no sail. The 16’ Boston Ship Chandler’s Whitehall on the next page seemed a bit narrow in beam for what I wanted, so we went back the New York Whitehall, stretched it to 15’11”, then added a centerboard and a sprit rig similar to the Boston Whitehalls. We also decided on lapstrake planking rather than carvel because it is stronger, lighter, and we wouldn’t have to wait for the seams to take up.

Blake family archives

Blake family archivesMy great-grandfather’s boat, VIOLETTA, sailed out of Pass Christian and was a favorite of the family. Family lore is that the boat is a New York Sloop and that it’s not likely that he built the boat. The burgee for the Pass Christian Yacht Club flies from the forestay.

I don’t know how far back my family’s connection with boats goes, but I know as soon as he was able, Benson Blake bought a second house in Pass Christian on Mississippi’s Gulf coast. The city established the first yacht club in the South in 1849 and preceded only by New York in the whole United States. When the club opened, Benson already had a house nearby, and he visited whenever he could. We don’t know what boats he owned or sailed, but his children grew up steeped in boats. When they were older they sailed the family sloop, VIOLETTA.

The wood that would become CURLEW was grown, sawn, and air-dried here on our land. We wait patiently for trees to die or show signs of disease, then harvest them and drag them to be cut on the small family mill. We cut mostly sassafras and walnut, but we also cut a mix of locust, cherry, ash, poplar, and others. I was telling someone from farther north that we build boats out of sassafras and he looked at me as if I were insane. That may well be, but sassafras is a great, moderately rot-resistant wood. In some parts of the country it doesn’t grow beyond the size and shape of a shrub, but here it can grow up to 24” in diameter, with 40’ of length until the first branch.

Blake family archives

Blake family archivesThis 50”circular-saw mill cut much of Dad’s lumber. We now have a bandsaw mill; it’s not nearly so scary.

Our current sawmill is a light, relatively safe bandsaw mill, but the circular-saw mill that cut most of the lumber for my father’s boats sticks out in my memory. His 1942, John Deere Model A tractor sat popping about 50’ from the mill, and a long, twisted flat belt connected the tractor’s flywheel to the mill, powering the 50″-diameter circular blade. The carriage and the setworks holding the log would fly down the track when my uncle, riding the carriage, pulled the lever and engaged the drive mechanism. The blade whined as it cut through the logs and boards fell off on rollers that were then neatly stacked in piles ready to be moved to the shed for drying and storage. Milling was a beautiful sight. A spinning 50″ blade is a rightfully terrifying thing, and the pile of sawdust it could make in a day’s work was enormous. The bandsaw mill is practical, but much less interesting.

Blake family archives

Blake family archivesDad built this little car for me and when I was about 15. He and I built this skiff, OTTER, with lumberyard pine. My cousins, a few of them seen here, were usually part of our boating adventures. Those are iron wagon wheels on the trailer. It was not meant for high-speed travel.

It is fortunate that we grow our own trees and cut our own lumber because we are always building something—little houses, furniture, airplanes, homemade cars, musical instruments, and whatever other oddity strikes us—and we don’t have to worry about the cost of lumber. There’s always a good supply of it, stickered in the old stable. We have actually been paid to build some things for other people, but for the most part we build for building’s sake. It is just a bug that bites us now and again. My work as a musician was more flexible than as a teacher and when I found myself with some free time—which is all it takes for a Blake to start building a boat—a good supply of air-dried boat lumber was already at hand.

Although a fair share of boats here have been built by eye, Dad and I decided to loft full-size as it makes things simpler in the long run. The Whitehall would be just a hair shorter than 16’, so two pieces of cheap, thin plywood were all we needed to do the lofting. We laid two sheets of doorskin end-to-end on the shop floor, tacked them down, and got to work drawing from Chapelle’s table of offsets on our stretched station spacing. Offsets are not always the key to a fair hull; even someone as highly regarded as Chapelle occasionally gets a number in the wrong place, so we were careful to stand back, eye the battens, and let them have the final say. It was a tedious process and seemed to take longer than it should, but it allowed me to hope that my first boat would not blemish the family reputation.

Blake family archives

Blake family archivesMy great-great-grandfather, Benson Blake, seems to have been nudged his son Daniel Warren Blake toward an appreciation for boats when he was very young. Although the boat young Daniel posed in for this photograph wasn’t real, Benson’s influence has extended through five generations.

My great-grandfather, Daniel Warren Blake, would no doubt have done a better job with the lofting than I did. I have seen his thesis from Cornell, where he majored in steam engineering. His precise hand-drawn design for a triple-expansion marine steam engine was a beautiful work of art. He was a real adventurer and led an exciting life. His boyhood time on VIOLETTA was just the beginning of his voyages. In 1898, during the Spanish-American War, he saw action while serving aboard the USRC MANNING, a 205’ converted revenue cutter. Soon afterward, he joined the Marines and sailed on the second USS MAINE, a 394’ battleship, relieved the garrison at Peking during the Boxer Rebellion, fought the Moro insurrection in the Philippines, crossed the equator several times, rounded both Cape Horn and Cape of Good Hope, and took pictures of his travels along the way. He left a big legacy, and Blakes have been bouncing around in his shadow ever since. He kept a shop at his house in Pass Christian and built small boats to be used in the waters there. The workbench and tools that he used are now in my shop and played a role CURLEW’s construction.

Julia Blake

Julia BlakeDad and I set the molds on the backbone while it was still resting on the lofting.

Having finished lofting, Dad and I came to one of the more difficult parts of building CURLEW: her stem. Chapelle’s drawings called for a rabbeted stem. A false stem could certainly look just as good and wouldn’t require the fuss of fitting the plank ends, but I decided to do it as Chapelle’s drew it. In our stockpile of lumber we found both a piece of walnut that had a sweep of grain that matched the curve of the stem down to the waterline and a walnut knee with which to make the sharp turn at the forefoot. We scarfed the two together, carefully took the bevel markings off the lofting, and carved the stem rabbet by chisel to the proper depth and bevel from garboard to sheerstrake. When finished we bolted the stem to the black locust keel plank.

At its widest point the keel is almost 9″ across, wide enough for the boat to sit upright on the beach without resting on the laps at the turn of the bilge. We have a lot of black locust on the land, and the family, Dad particularly, has always used it for keels, cleats, frames, and even planking on larger boats. It’s is a great wood anywhere we need a tough, long-lasting and rot-resistant wood.

The New York Whitehall has a beautiful wineglass stern that can show off a beautiful piece of wood. I found an 18″-wide slab of walnut my father cut years ago on the circular-saw mill that I could use to make the entire transom in a single piece. It came from a large, branchy walnut that grew in a pasture on the land. It had died some 30 years before and was subsequently cut into lumber. The trunk was not long, perhaps 6’, but its circumference was such that it had to be split before it could be cut with the 50″ circular blade. I did not have a piece of locust both wide and thick enough to make a rabbeted keel. Some of Chapelle’s designs seem to show a simple butt joint where the garboard meets the keel. In those cases, Dad often treated that seam alone like a carvel design and drove cotton roving, but I wanted a dry boat that could be trailered without having to wait for any seams to take up. So we used a wide piece of juniper to make a keel batten over the plank keel, effectively creating a rabbeted keel.

Julia Blake

Julia BlakeDad sits in the “moaning chair” contemplating the battens sprung along the sheer. The boys, meanwhile, took a more active approach and hit things with hammers.

We would build the boat right-side up, as my father built his boats, as many of them were too big to flip. It’s also easier to inspect the fairness of the hull. The six temporary molds we built out of ash, blown over in a big wind some years before, and set them up on the stem, keel and stern. It was time for planking up.

Dad and I did the planking with 3/8″ sassafras. We rarely cut boards over 14’, so we scarfed them at a ratio of 12:1 using resorcinol. Though that particular adhesive is getting hard to find, we were able to order some from the U.K. My father has always preferred it to epoxy, though others find it finicky. I have used both for various projects and have had great luck with it. It cleans up with water—certainly easier to clean up than epoxy—and I have never had a joint fail. I can’t say the same of my experience with epoxy.

Julia Blake

Julia BlakeAt the turn of the bilge, there is less twist at the stem and the planking only gets easier from this point on.

I was afraid the garboard would need steaming, as the twist was significant and the forefoot hollow, but with a little training, the sassafras bent easily. After the garboards, twist and hollow in the rest of the strakes diminished, and the rest of the planking went pretty quickly. The planks were fastened with 1-1/8″ copper clout nails from D.B. Gurney’s, a Massachusetts company that has been making copper and brass tacks since 1825. The changing bevel as each plank met the next was a bit tricky, but each mold provided a reference for the angle of the bevel. The laps became shiplapped as they met the bow and stern, courtesy of a rabbet plane that belonged to my great-grandfather.

Julia Blake

Julia BlakeShe looks like a boat! This was a good opportunity to put a first coat of paint on the inside before the frames went in. The boys look at the fully planked hull with approval. On the ceiling above them are rows of Mason jars holding miscellaneous fastenings.

The sheerstrake is of black cherry that came from a fine tree that blew over on my wife’s grandfather’s land a decade ago, and was 7/16″ instead of 3/8″. A slightly heavier sheerstrake looks good, especially with a molded bottom edge, and adds a bit of extra stiffness at the gunwale. The cherry I found harder to work with than the sassafras, locust, or walnut. The surface planer, a 12″ Parks from 1948, tried to pull the small burls right out of the plank, and the grain was contrary in many places, even as I tried to scrape it, but in spite of the difficulties it posed it ended up giving a nice mid-tone contrast to the other woods used. Dad and I anchored the planks ends, stem and stern, with Monel Anchorfast nails with the little anchor on every head.

For as long as I can remember, all of the fastenings in the shop have been stored in glass Mason jars with their lids screwed to the rafters. It is an easy and convenient way to store them, and you can see what they are without having to take them down. This is where I found the old Monel nails. They must have been kicking around for decades in the shop, courtesy of my boatbuilding ancestors.

Blake family archives

Blake family archivesGrandfather Daniel bought this boat surplus between the World Wars. Here it lies grounded in the mud up a tributary of the Mississippi. We have all had our share of misadventures.

Another tradition that dates back to my great-grandfather, Daniel Warren Blake, is building boats here on the land and sailing them down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico. He and his brother, Henry, built a boat here in the late 1880s and sailed to the Pass Christian house on the coast. This tradition has made for many adventures…and a lot of discomfort and danger for the subsequent generations who have taken up this practice.

Blake family archives

Blake family archivesGrandfather Daniel and his friend Waverly prepare to head downriver in I HOPE. With the powerful searchlight on the bow, they could travel at night.

My grandfather took I HOPE, the motor dory he built, down the river in the late ’30s. Fortunately, he had a Nadler two-cycle inboard engine for power. Or perhaps not so fortunately, as the Nadler has no real throttle or reverse. You reduce throttle with the spark advance. It burns the same amount of fuel no matter where the “throttle” is set. To reverse you allow it to almost die, wait for the flywheel to kick back, move the spark advance, and it will start turning backwards—sometimes. My father, my uncle, and I have made this trip as well with various misadventures along the way. We have all made it through alive, but towboats, sandbars, and sudden squalls have made for hair-raising adventures.

Frances Blake Perkins

Frances Blake PerkinsTHELMA TUGGARD was powered by two electric sewing-machine motors and was thus one of the few “twin screws” the family owned. Grandfather Daniel Carmichael Blake built the boat, but my uncle Henry was the undisputed captain.

I am not sure if my great-grandfather dreamed of building boats while he traveled the world, but my grandfather, Daniel Carmichael Blake, certainly did. He did a brief stint in the Merchant Marine in the early ’40s and then was in the Army for the rest of World War II. He was stationed in India, and I got the impression that he spent the whole time there dreaming of boats. He converted the top of a building in Calcutta to an experimental test basin and sent models, tied to a weight that was dropped over the edge of the building, ripping along a trough of water. There were so many people in Calcutta that there was always a crowd of people at the bottom of the building waiting to pass the weight back up to him. I have several of William Atkins’s books with inscriptions in the front that read “D.C. Blake, Calcutta, 1945.” How he bought them in India, I do not know, but he could not wait to get home and start building boats again.

Julia Blake

Julia BlakeDad and I worked side-by-side to rivet the steam bent-frames to the plank laps.

Planking complete, it was time for the steam-bent frames. I did not have fond memories of steamboxes. When I was a child I stuck my hand in one, despite many warnings from my dad and uncles, and learned a painful lesson that stuck with me. I found a piece of triple-wall stainless-steel stovepipe in the garage and an empty Christmas cookie tin. My father figured out what else I’d need, came up with a radiator hose, a crawfish boiler, and a piece of water pipe, and the steamer was ready in about an hour. He has a knack for seeing and creating simple solutions.

Frances Blake Perkins

Frances Blake PerkinsDad started building boats early and did sea trials in the old swimming pool.

My father, Daniel Blake, has built around two dozen boats over the years, and he has made the customary trip down the river more frequently than any other member of the family. Three times he has braved the mosquitoes, tugboats, and rain to get to the Gulf of Mexico. His original destination was far out into the blue, perhaps inspired during his years in the Navy yearning for the freedom to do as he pleased, or perhaps by his uncle Paul Nones, who had twice crossed the Atlantic in his 40’ sailboat.

Frances Blake Perkins

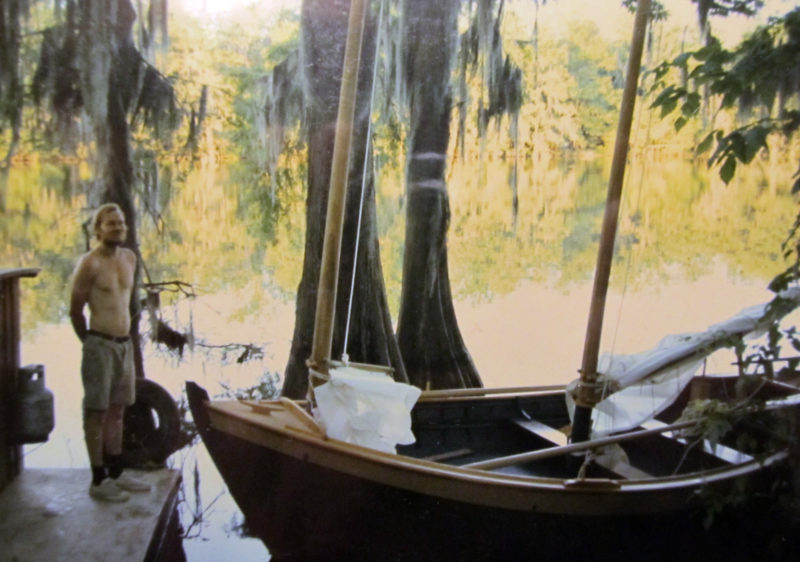

Frances Blake PerkinsWe do all our debugging in this little local cypress-lined oxbow lake. We can safely say Dad’s MERRY SAVAGE was the only Block Island boat to ever be in that lake. The boat’s name was a play on the name of Benson’s second wife, Mary Savage Conner.

Frances Blake Perkins

Frances Blake PerkinsBOGLE, a 34’ Galway Hooker that Dad built, was moored in the Yazoo swamp before its big trip down the Mississippi River. From this voyage we have his diary, which chronicles, in detail, the miseries suffered by the participants.

Blake family archives

Blake family archivesBOGLE went down the Mississippi River and sailed in Gulf of Mexico bluewater for a few days and ended up in Gulf Shores, Alabama. A few months later Dad sold her and she went to Mystic, Connecticut. She was owned by a dentist for many years until he got too old to sail anymore. In the mid 1990s, he called Dad and had to fight back tears to tell him how much the boat had meant to him. We don’t know where BOGLE is now.

The Florida panhandle was as far as Dad got in his own boats. Bradley, one of my uncles, went along with Dad downriver on his second voyage and kept a log. Much of it reads like this: “Day 6, it is still raining. There is no wind. The others maintain an attempt at optimism, but it is clear that they are beginning to go insane.”

Blake family archives

Blake family archivesThe 31’ MERRY SAVAGE II is a boat Dad designed and built. In 1991, he took me with him aboard her for a trip down the Mississippi River. Dad eventually pulled the bilge keels off.

I went down the river on one of Dad’s voyages when I was nine. Two things stick in my mind about the Mississippi. First, towboats throw an unbelievable wake behind them as they head up against the current. The second is a memory of my father using a champagne cork leftover from the launching party to fix the sailboat’s auxiliary Volvo diesel after it died mid-river. My poor mom was along on that trip as well, and she spent most of the time terrified. The family cat that came along was terrified, too. In fact, during a particularly bad squall it got on deck and bit Dad on the foot as he was attempting to navigate a particularly nasty channel. We docked in Apalachicola, Florida, and that was the end of the voyage. The cat and Mom were glad to set foot ashore again and we stayed in Apalachicola for 10 years.

Blake family archives

Blake family archivesJUBILEE was Dad’s first steel-hulled boat; her superstructure is juniper. He built her in our backyard in Apalachicola, Florida. A neighbor complained, but the zoning guys were fisherman and said boatbuilding was not listed on the books as something you couldn’t do in town. So it all worked out.

It wasn’t long after that dad got his 100-ton license and took a job sailing GOVERNOR STONE, a 63’, 1877 schooner for charter voyages. Soon after, he decided to go into business for himself and built a 50’ paddle-wheeler to take his own tours out on the river.There were several other boats he built in Apalachicola—a Sharptown barge, a houseboat, and two skiffs for me.

Blake family archives

Blake family archivesDad built the 50’ JUBILEE to take passengers out. She was powered by a four-cylinder Palmer gasoline that my grandfather bought new about 1950.

Mom and Dad returned to the family land in the early 2000s, and I returned a few years later. There were work, school, and more practical matters to attend to first, but eventually Dad and I found ourselves once again working together in the old shop on a boat, my Whitehall.

We wrangled over whether to use locust or sassafras for the frames, and decided to try sassafras, and so milled a slightly wider frame to make up for its relative lack of stiffness compared to locust. Coming straight out of the cobbled-together steambox, the frames bent in beautifully. Dad and I fixed the frames in place with copper rivets. I found copper nails and roves stored in the mason jars overhead, and after falling into a rhythm, we made short work of the fastening the frames. I did have to crawl inside the boat for the hard to reach rivets, but mostly we stood side by side. I would drill, drive, and peen; Dad would back. I made the centerboard of locust with heavy galvanized spikes “driven awry,” our way of saying driven at random angles, to hold it together. I cut a rectangular hole in the board, drove nails around the perimeter leaving the heads protruding, and poured 10 lbs of molten lead directly into the locust without ill effect on the wood. We made the floors of walnut, scuppered them, and held them in place with Anchorfast Monels driven through the laps and stainless-steel carriage bolts going clear through keel, batten, and floor.

There is a small stack in the corner of the stable where we keep various bent pieces of wood cut specifically for knees and breasthooks. I dug through this pile and found some walnut quarter knees, cut from forked limbs, and used them to connect the transom to the sheerstrake. There wasn’t a crook with an acute angle to serve as a breasthook, so I made it in two pieces. Two through-bolts passed each other inside this piece, one binding the two pieces of the breasthook together and the other binding it to the stem.

Julia Blake

Julia BlakeThere is a lot of sitting, staring, and thinking that goes into building boats. Our thoughts and conversations often wandered, but sometimes we’d get around to the boat in question. Here, the end is in sight.

About the time we had inwales, risers, and seats installed, my wife and our two boys grew much more excited about the boat. The closer it got to completion, the more often they visited the shop. I was glad to have their company and to see their interest in the boat. My appreciation and understanding of wood, boats, and tools began when I was their age watching my father at work. My boys must learn about boats if they are to be the next generation to build and sail them. I needed my wife to be interested too. She knows how to sew and I was hoping she would help me make the sail. I made the mast step and partners of locust, with heavy silicon-bronze carriage bolts securing the step in place, and rivets anchoring the partners firmly in place about 2’ aft of the stem. For large rivets we often use old pennies as roves. Those minted prior to 1982 are 97 percent copper. (Those minted in 1982 and after are copper-plated zinc and are unsuitable.) The pennies work great and they are cheaper than roves of the same size.

Julia Blake

Julia BlakeWith the seats and centerboard case in, Andrew and Patrick anxiously wonder when the boat will finally get in the water.

I didn’t have to work very hard making a mast. As I was looking in the shop rafters one day to see what boatbuilding supplies were there, I found a 12’ spar from a boat that had been built and sold 50 years before.

Julia Blake

Julia BlakeThe boat is ready for its debugging period in the local oxbow. Patrick is ready to step the mast.

Pete Culler was a big fan of the spritsail and I thought his reasoning behind it was sound. It is a simple rig, easy to set up, and the gear can stow in the boat without hanging over when not in use. This is an advantage in a boat that will often be rowed. With a spritsail, it is important that the mast be able to freely rotate in the step and partners, so I collared the bottom of the spar (and also where the partners met the mast) in copper, then rounded and greased the butt end. The mast was nearly complete.

Julia Blake

Julia BlakeI put the sail together in the living room. It was over 100 degrees outside, so the house’s air conditioning was a life saver.

My wife did agree to help with the sail. We thought about starting from scratch, but settled on sewing up a kit. That made quick work of the project and, one cheap sewing machine later (I had to replace it after the multiple layers of heavy sailcloth took their toll), the sail was complete. I made some nice 8’ oars out of sassafras, and ordered locks, cleats, and any other paraphernalia I could not find in the storage bins at the family shop.

Julia Blake

Julia BlakeI often launch CURLEW without the sailing rig. A wind map of the United States puts us in a dead zone, an inland Doldrums. Our winds in northern Mississippi are fickle at best, so rowing is a more likely proposition than sailing. I am teaching the older son to row and the younger will get a chance soon. There is a lot of splashing and very little traction with the oars so far.

CURLEW was in the water a few dozen times over the following fall and winter. There were bugs to be worked out, the rigging and maststep had to be changed somewhat, the centerboard needed adjustment, there was a pinhole leak in the centerboard trunk, but in May we had an official launching party on Lake Bruin in Louisiana. The wind was feeble and the weather hot, but CURLEW rowed like a dream.

Carol Lutken

Carol LutkenIf we had some wind, I’d happily sail off into the sunset with my boys and my wife Julia.

You truly own the things you build, and yet I don’t own this boat. I am just a link in a chain. The land that grew the trees came from my great-great-grandfather, the tools and traditions started with my great-grandfather and continued with my grandfather. I couldn’t have built the boat without my father’s help and experience; the legacy belongs to my sons. The shop is idle now and looks lonely. It’s time to build another boat. This time, perhaps it’ll be a motor launch for those days when the wind doesn’t blow and it is too hot to row? Maybe a boat that I can take my boys on that voyage down the Mississippi River? A good stack of lumber is already laid by. It all starts with a pile of boards.![]()

Nicholas Blake lives on his family land in Mississippi with his wife and two boys. When he is not playing music, he is building something in his shop or at his forge, wandering in the woods, messing about in boats, or fostering his family’s penchant for eccentricity.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

A fascinating chronology with technical anecdotes, telling the history of a family’s skill and love of boat design and construction, through the generations.

Thank you! I enjoyed writing it. Julia says hello!

I am researching history of TURTLE DOVE built by Daniel in 2001. Would like to know if there are any pictures/paintings of the original ship built by his father.

Love this. I grew up with Danny, Nick’s dad, and my dad was one of Nick’s grandad’s best friends. I absolutely remember the THELMA TUGGARD.

Hi Carol! The stories of those times could fill a book.

I had to chuckle at your reference to “the moaning chair.” Howard Chappelle said that every boat shop needs one, so, it appears your shop is complete! Fortunately, but not due to my boat carpentry skills, I have only had to use mine occasionally.

CURLEW went together with little fuss. My current boat, yet to be named, has employed the chair far more. That is what lofting 1/4 size and tweaking by eye as you proceed will do, I suppose. I am nearly finished now, I stood back this morning and thought, “It’s a miracle, she looks pretty good.” In a few weeks, I guess I will see if she floats as good as she looks.

The Violetta’s hull sure looks like a Gil Smith catboat from the Great South Bay of Long Island, New York.

Yes, to be honest I am really not sure what she is or where she was built. Maybe a one-off by a Gulf Coast builder, perhaps brought down from more northern climes? The last of the folks who could tell me for sure died in the ’50s. I hear the folks at WoodenBoat are puzzling over her, maybe they can shed some light. I will have to have a look at a Gil Smith Catboat hull.

Wow, Nick, this is so amazing. I actually took videos of Danny while he was building the boat in his backyard. I sure wish I can find them. I’ll keep looking. Amazing!

Those would be fun to see. Glad you enjoyed the article, Janice.

What a grand story of a family boat building tradition going way back. What treasures the Mason jars in the overhead must hold. The moaning chair reminds me of a long bench next to the sun-warmed brick wall of WoodenBoat School. At lunch time after some hard boatbuilding by a bunch of older folks the bench earns its name, “ the moaners bench.” Thanks for giving me an hour of wonderful mind wandering.

Thanks! I am glad you enjoyed reading it. I certainly enjoyed writing it. CURLEW was meant to be my experiment with boatbuilding as an adult and a way to connect with my dad and the previous generations, but now I am hooked. HERON, a 20′ motor skiff, is about to roll out of the shop now. I am already planning a 14′ faering build after this. I did some wood carving for a church a few years ago and I thought I might ornament the stem on the faering with relief carving. Yes, it is official, I am hooked.

Thank you again!

Nick

Thank you for reading my article! I think there have been a couple of famous CURLEWS, and maybe even a design with that name. The idea for the name was twofold for me. First, there is a line in a Longfellow poem, that mentions “the curlew’s call.” It was called “The Tide Rises and the Tide Falls.” My taste for the fireside poets sent one of my professors into hysterics in college. Which doesn’t bother me at all, I didn’t like his taste in poetry either, so it all works out! Second, my bird book says that the Curlew “is a rare visitor to Mississippi, but has been spotted on occasion due to variations in migration.” This seemed applicable for a small wooden sailing boat in Mississippi, which is also a rather rare thing.

Thanks again for reading,

Nick

This the most interesting site on the web.

I must go back and read it all again.

CURLEW? Rings a bell. There is a famous wooden sailboat by that name, very old, wish I could remember,oh well, thank you very much.

Thanks!

Very well written. Fascinating story, great photos

Nicholas, this is a wonderful story about a wonderful family! I’m proud to be your cousin. It was a pleasure to spend vacations with your dad, Sister, Bradley and Henry. I remember when your grandfather had built a boat for each child for their house at Cotton Bayou. Carmichael and Fran were my parents’ favorites, and we have many good memories of times with the Blakes. Each of your grandparents was a cousin of my dad Richard Conner, and he claimed to have introduced them. Kudos to you for weaving your family history into the record of your many family boats!

Thank you!

I have heard wonderful things about Richard Conner, and of course it is always nice to hear from my Natchez cousins. Although the seeds and the branches spread far, we draw from the same root. All the best, cousin!

Thanks again for reading,

Nick

Able Seamen Patrick and Andrew will work their way before the mast, soon to pay out line on their own vessels. One foot on the gunwale, one arm in the rigging, they will scan the horizon for friend and foe, reading the sea as they do the lay of a rope, and bringing life’s bountiful haul on board for celebration. Such shall boldly be the future, and let the timid stand on the shore.

Henry L. Blake

[From the author’s uncle. Patrick and Andrew are the author’s sons. —Ed.]

That’s talk to stir the coals of a sailor’s blood! Blunderbusses and cutlasses stand ready! May the galleons they chase be fat, slow, and poorly armed.

Nick, what a great and loving story. My name is Mel Oakes and my father, Fred Oakes, was a friend of your grandfather. I was privileged to spend a few hours with your family during the construction of the BOGLE. The beautiful handmade tools used to build the boat were a joy to behold. Mr. Blake gave me a couple of pieces of persimmon which I still prize. Since I had a love of steam engines, he gave me a tour of the family engine he was restoring. As expected his work was flawless. I later sent him some information about steam engines and he kindly sent me a small photo book of the engines he had put together. I have added these pictures to a web page on my family website with some research I have done on the engine. My brother, Donald, still lives in Vicksburg. Again, many thanks for this very special article.

Nicholas, so very pleased to learn more about your family’s long boatbuilding legacy. Especially happy to see photos of your dad, Dan, with whom I spoke 3 or 4 years ago. I have owned MERRY SAVAGE since February 1999. When I bought her from her 2nd owner, Tom Farbanish, she carried no name. Because I love traditional wooden working boats, I felt she should carry a name that reflected my heritage and hers. She now sports red “tanbark” sails and is named SAUDADES, a Portuguese term whose closest English equivalent is Nostalgia.

Ironically, when I bought your Dad’s boat, I had recently purchased a summer house in Wickford, Rhode Island, where, although I did not know it at the time, Paule Loring had built his Block Island Double-ender in 1948 from lines he had taken off the last surviving hull of her type on Block Island. It was from Paule’s boat that Howard Chapelle took the lines for the design he included in his American Small Sailing Craft, which your Dad used to guide his build of MERRY SAVAGE!

Talk about a design coming full- circle!

I take great joy in admiring, working on and sailing my boat that your Dad built. Whenever we sail, she draws admirers: power boaters turn 90 degrees off their course to speed over for a look. Sailboaters, being a bit more reserved, fall-off or head-up to sidle on over to “speak us.”

Please thank Dan again for the solid craftsmanship he built into her. Built in 1985, she creaks just a bit from her 33 years of shouldering aside our typically short, nasty Narragansett Bay southwesterly 2′ to 4′ afternoon chop, and from her swaying, unstayed solid 30′ masts, but is still solid, and this past fall had her garboards recaulked for the first time since your Dad built her. That bespeaks a first rate job of joinery. If you or your Dad ever get up here to Wickford, I’d be mighty pleased to have you come for a sail.

Your young boys are very lucky, I hope they get bit by the boatbuilding bug, and not get into many of those mindless video games. Outdoors is where it’s at. And make sure they know how much God loves them, and try to avoid sin, as it leads to ruin in many ways.

Nicholas,

A truly beautiful read which helped me recognise so much of my own history and culture and view of life.

A veritable family reunion in the comments! I don’t think I’ve ever read an article in WB or SBM that weaves together the personalities, family history and boat building so well. Families like the Blake’s made the US a great country.

Nick ~ are you still up in the Vicksburg area? I am just down the river at St Francisville (& Bayou Sara), and have double ender, a Nimble 24, that one of these days needs to follow that path south on the big river!