There is something deeply satisfying about prolonged outdoor physical exercise when your body is injury-free and working well, when your muscles, tendons, and bones have overcome their initial protest at being asked to do the unaccustomed work and become conditioned to it. Long-distance cyclists and marathon runners know this, and as a former enthusiast of both of those pursuits, I, too, know it. However, for me, long-distance rowing delivers the most gratifying way to experience that ineffable feeling that comes from spending days and weeks at a time in the natural world moving under my own power. Thinking back over the various small-boat journeys I’ve made through the years, there is one day in my memory that epitomizes that feeling of fulfillment. It came aboard FIRE-DRAKE, my 18′ sail-and-oar boat, 10 days into a cruise south from Prince Rupert along British Columbia’s Inside Passage.

Early in the morning, under the last remnants of the overnight rain and with the roar of Butedale Falls receding beyond my boat’s transom, I rowed away from a ramshackle float at the abandoned settlement of Butedale. It was just another day of cruising in Princess Royal Channel, the steep-sided narrow trench between Princess Royal Island and the mainland, where the outer-coast weather forecasts only loosely corresponded to the actual weather in the passage. The previous day’s sailing wind had given way to calm in the morning, but I was grateful it was not a headwind. Although the flood tide was making against me as I rounded Redcliff Point and turned south along Graham Reach, I knew that I could make progress if I worked close to shore in the back eddies created by the small points and indentations resulting from the folds of the mountains where their feet met the sea.

Tim Yeadon

Tim YeadonAlex Zimmerman was on a 300-mile cruise, with his friend Tim Yeadon in July 2016 when they called in to Pender Harbor on the east side of British Columbia’s Strait of Georgia. Before his AFib diagnosis, Alex thought nothing of long-distance rowing cruises, whether in company or alone, and relished the challenge of a multiple-day expedition under oar and sail.

The chill of the damp morning yielded to broken cloud with glimpses of sun between the mountain peaks. I shed a layer, drank some water, planted my feet firmly on the stretchers, and settled into my all-day pace of about 25 strokes a minute. Each stroke was a cycle: pushing the oar handles aft, dipping the blades of the oars into the water, pulling with extended arms, then completing the stroke by bringing the handles to my chest. The repetition soon became nearly as automatic as walking or running. I breathed easily in the crisp, clean air and the rhythm induced a kind of moving meditation, where the awareness of my body’s working was present but not uppermost. My mind was free from whirling jumbled thoughts, free to just be, and to absorb what was happening around me. Rowing close to the shore, I noticed all the little trickles, rills, and streams that would otherwise be hidden by the overhanging cedars, whose lower branches were trimmed by the high tide as neatly as by any gardener. The aural liquidity of a Pacific wren’s song, the scold of a Steller’s jay, and the hollow “quock!” of a raven testified to the unseen presence of deep-forest inhabitants. For some reason there was no other boat traffic that morning, and I felt that all this had been laid on especially for me.

The hours wore away, and the landmarks of my progress along the channel successively ticked by—Aaltanhash Inlet, then Asher Point guarding the entrance to Khutze Inlet to port, a brief puff of wind at Griffin Point that nearly tempted me to raise sail. Carrol Island came up to starboard, and I rowed through the narrow channel behind the island just because I could. In late afternoon, nine hours after I had started, as I approached Netherby Point at the mouth of Green Inlet in search of an anchorage, I was physically tired, but I had a profound sense of accomplishment and felt there was no other place or time I would rather be.

As I coasted into the bay, I was supremely grateful that, even at the age of 66, I was still physically able to do this. I was grateful to have been able to arrange my life to be there in that place at that moment, to row a loaded boat that I had designed and built down this storied stretch of coast. The experience was a privilege that few can access, and I believed I could keep doing it for years to come.

Dave Lesser

Dave LesserAlex designed and built FIRE-DRAKE to replace the Whitehall he had rowed and sailed for seven years. The new boat sailed well to windward but at times Alex found the best option was to lower the rig and row. But the characteristics that gave her better sailing abilities in comparison to the Whitehall—more beam and wetted surface—also made her harder to row. For Alex in recent years, that extra work became too much.

It wasn’t to be. Several years before that cruise south along the Inside Passage, I had experienced some intermittent heart-rhythm fluctuations that came and went. As an otherwise fit amateur athlete who had never smoked, never been overweight, had low cholesterol and normal blood pressure, I didn’t think much about it. I put the episodes down to too much caffeine and cut back somewhat. I woke up one night at home, however, with another of these episodes, and by the following afternoon it hadn’t gone away—my heart had not gone back to its normal rhythm as it had before. I finally had to admit this was not normal. My wife drove me to the hospital emergency department where we checked in and sat in the waiting room with others who, like me, showed no obvious symptoms but didn’t look well.

Eventually, the verdict was delivered—I had atrial fibrillation, AFib for short. It’s a condition where the electrical signals for the heartbeat are extremely irregular, weak, and usually rapid. I learned that there were several varieties of AFib and that mine was paroxysmal AFib, which happens unpredictably in distinct episodes. I was administered a cardioversion, a mild shock to jolt my heart back to normal rhythm, and while it did not reset the rhythm, my blood pressure wasn’t too low and I wasn’t feeling as bad as most people apparently do, so I was discharged. I went home where, 16 hours after the start of the AFib, my heart rhythm reset on its own.

After that visit to the ER, I went through tests and consultations with specialists. Stress tests revealed that my heart had the strength and stamina of a much younger man. That was gratifying. Given that my AFib was intermittent, my doctor prescribed a drug that I could carry with me and take whenever I had an episode; it should reset the rhythm. I was also told to drink more water and add a little salt (which I had avoided for years) back into my diet. That regimen seemed to work pretty well, at least for the next few years. There was one two-year period, in fact, during which I had no episodes at all.

Tim Yeadon

Tim YeadonIn FIRE-DRAKE Alex would often row for up to eight or nine hours a day, frequently alone, and sometimes in bad weather and remote places. Here he is north of Yaculta Rapids in the channel between mainland British Columbia and Vancouver Island.

I wondered what had caused my AFib and why I, who had led a very active life, had it. I learned, to my dismay, that I may have been too active by exercising too hard and too long for too many years. One doctor pointed me to a couple of studies that found that the incidence of AFib among marathon runners and cross-country ski racers in Europe was three to seven times that in the general population. Later, a friend recommended The Haywire Heart, a book that details heart problems among athletes, especially AFib. It confirmed and amplified the findings of those earlier studies. There was a high likelihood I had unwittingly caused the problem. More to the point at this stage, was that if I continued doing what I had always done, I was likely to make the AFib worse.

I did not want to hear that nor admit it to myself, and it took me a long time to accept it. It was something of an existential crisis. I had always defined myself, at least in part, by what I could do physically. I was the guy who had more stamina than most, the one who could persevere and make it through just about any physical challenge. If I could no longer do that, who was I? Now I had a condition where doing that could harm me. I’m a little thick sometimes, but eventually it sank in that going out and rowing for eight or more hours a day for weeks on end during a cruise was no longer a recipe for growing old gracefully. I grieved for the man I once had been, and belatedly accepted I could no longer do what he did.

I caved in and bought a 2.5-hp outboard to propel FIRE-DRAKE in the calms, but after a number of weeklong trips, I found it was not a congenial match. The boat was relatively lightly built, and I worried that the vibration from the motor might do long-term damage to the structure. The stern was not suited for the outboard—it had to be mounted on the gunwale, which I found very ugly, and taken off and stowed every time I wanted to sail. Stowed, it took up room on board that could be used for other gear. After much pondering about whether I could build a well for the outboard (awkward given the existing structure, plus it would eat up stowage space), or convert to solar electric (not enough area for needed solar panels and a lot of added weight for batteries), I concluded that if I wanted to keep making extended voyages along our wonderful British Columbia coast, I really should do it in a different boat, a motorsailer of some kind. I still wanted to sail when the wind served, but the boat should be happy motoring all day in the calm and/or the rain that we get up the coast. The rain also meant that if I could find something with a small cabin, so much the better. I could have bought a used, small, production cruiser, but I liked having an excuse to build another boat. I made this decision a few short months into the COVID-19 pandemic, so it would be a project to keep me occupied during the lockdowns.

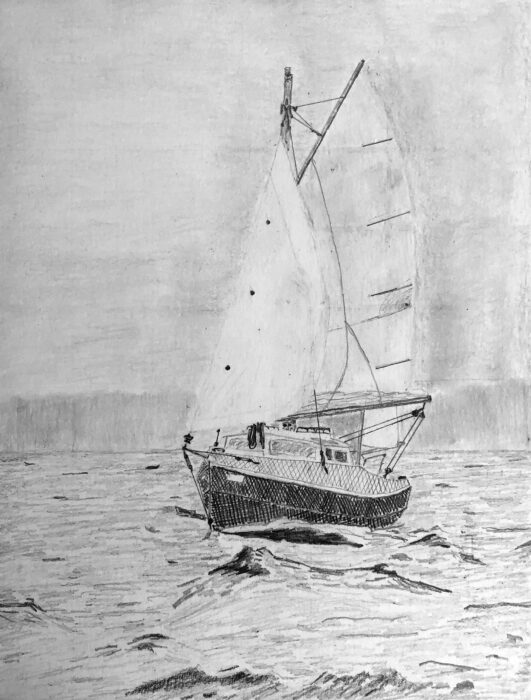

Alex Zimmerman

Alex ZimmermanAlex’s sketch of CAMAS MOON gives no sense of a man taking the easy life as she cuts through choppy waters under a reefed mainsail but full jib and mizzen.

Which boat to build? As I would mostly be cruising solo, I didn’t need a big boat. I didn’t want the expense of a boat that had to be kept in the water, so it had to be trailerable. FIRE-DRAKE, at 18′ long and 5′4″ wide, was the biggest boat I had built in the shop. After re-examining the space, moving things around, and offloading a radial-arm saw that I didn’t use much, I figured I could build a boat of about the same length, but a little wider. All these considerations led me to Tad Roberts’s Pogy 17 design, which is, as he puts it, “a minimum coastal cruiser for one or two people.” When I contacted him and said I was ready to order the plans, he told me that the detailed plans had never been developed, as nobody had yet built one. Tad proposed designing a slightly different solution for the same mission, and it sounded like an even better fit for what I had in mind. He named it the CoPogy 18, an 18′ gaff yawl with a pilothouse cabin and an outboard motorwell. I started the build in September 2020 and, at the end of August 2022, launched CAMAS MOON.

My shakedown voyage in September 2022 was a two-festival cruise, first motoring the 8 miles from my local launch ramp around to Victoria’s inner harbor for the Victoria Classic Boat Festival. Then I motored in the calm and the heat across the U.S. border, through the San Juan Islands, and south across the Strait of Juan de Fuca to take part in the Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival the following weekend. After that, I returned home the same way, a 140-mile round trip. I came away from the cruise with a list of nearly three-dozen fixes, modifications, and improvements to be done over the winter. I got started right away. What also got started that fall was a return of my AFib episodes, which had been absent for two years. My meds still worked to reset my heart, so I wasn’t too worried, and the rest of the winter passed without more episodes. At the end of May, I had another major episode at home, but the drug still worked. Not so the episode that came three weeks later. The drug not only didn’t reset my heart rhythm, it turned the atrial fibrillation into atrial flutter, apparently a more dangerous condition because the heart beats even more rapidly. I checked myself into the emergency department again and was successfully cardioverted back to normal sinus rhythm.

I had planned an extensive summer cruise for 2023 and was eager to see how the boat would perform with my modifications, but this last episode had me worried. In a follow-up talk with my doctor, he thought that the risk of it happening a second time was low and that the meds could still work if it happened again. Accordingly, I planned a cruise for late July.

Galen Piehl

Galen PiehlCAMAS MOON, with Alex at her helm, sailed in the Victoria Classic Boat Festival during their shake-down cruise in September 2022.

The morning of Thursday, July 20, I launched CAMAS MOON at the public dock in Sidney, B.C., and headed out. I had a very pleasant warm-weather sail in sunshine and light winds, with some motoring, over to Bedwell Harbour on South Pender Island, and arrived in midafternoon. As I was raising the centerboard, I heard a bang—the lift pennant had broken. I had to fix it somehow, and after thinking about it, came up with a jury-rig solution using the materials I had on board. It took me three hours down in the cabin in the heat, to complete the repair. By then I was tired and somewhat dehydrated. I drank some water, but probably not enough. As the sun went down, I moved CAMAS MOON over to a park mooring buoy, which was a little more protected from the swell that had started to roll into the anchorage. I went to bed a little early but woke at 11:15 p.m. to the familiar disturbed rhythm of AFib. I took my meds right away, but the AFib didn’t reset on its own. I was up to pee every hour through the night, one of the effects of AFib, which likely aggravated my dehydration. I got up for the last time at 5 a.m. and although I didn’t feel too bad at that point, I decided I couldn’t continue the trip. I needed help.

I slipped the mooring buoy and motored back to Sidney in the calm. I arrived at about 7:30 a.m., and luckily got a berth in the nearly full marina. The only spot left was on the very last float at the end of the last dock, 500 meters from the office and ramp. I called my wife to come to pick me up. I made three trips back and forth to the office to check in, back to the boat to fetch stuff that I didn’t want to leave on board, back again for a couple of important items I forgot, and then back up the final time, feeling more tired each time, having walked nearly 2.5 kilometers by then. I was feeling more and more light-headed as we drove to the emergency department at our local cardiac hospital. About three-quarters of the way there, it was so bad that I had my wife pull over and call 911. I was dizzy, nauseated, sweating, and apparently my color was not good. I felt like I came very close to passing out. I got out of the car and laid down on a lawn.

Paramedics arrived very quickly, first a fire truck, then an ambulance. My blood pressure had become very low, just 80/60. They loaded me into the ambulance and took me to the emergency department. It was very busy, so it was nearly three hours before I got to see a doctor. I was dehydrated and very thirsty, and my heart had gone into a flutter again, but at a higher rate than it had a month before. The paramedics got a drip going in the ambulance and dripped in about 1.5 liters of saline. As I waited, my blood pressure started to come back up. According to the ER doctor, it is likely that at least part of the unusually low blood pressure I experienced was due to low blood fluid volume. More of the usual tests followed and once again cardioversion was administered, which restored sinus rhythm with just one jolt. By then it was 2 p.m., nearly 15 hours after the AFib had started.

Alex Zimmerman

Alex ZimmermanAfter leaving Victoria, Alex motored south through the San Juan Islands and across the Strait of Juan de Fuca to the Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival. The 140-mile round-trip cruise is the only long-distance voyage Alex has completed in CAMAS MOON but he’s still hoping there are more cruising adventures to come.

Would the AFib have had such a severe effect on me if I had remained properly hydrated? I can’t answer that. The other big unanswerable question I have, of course, is what if this had occurred later in the trip, when I was more than a couple of hours away from a marina? I’ve always hoped I would never have to call on the Coast Guard to get me out of a situation I could have avoided through better judgment or decision-making, but I am not ready to take the consequences of a bad decision and “die like a gentleman” either, rather than call for help. And if I had been even farther away when I called for help, what then? I might not be here to tell the tale.

It is early November as I write this, and while my AFib situation has clearly taken a turn for the worse, I feel fine at the moment and day-to-day. But I feel as if I am tethered to an emergency department. After more consultation with the cardiologist, I now have a treatment plan for my AFib that, if it works as well for me as it has for others, should allow me to get out and voyage solo again. I should know within a few months.

Through all this, have I experienced some transformative epiphany around affliction and aging? Not really. Everyone who has ever lived has been born under a death sentence. I think it took me longer than most to internalize that, and to recognize that my end might not come suddenly but via a slow decline. Regardless, I believe life is to be lived to the best of my abilities. If age, infirmity, or both mean those physical capabilities no longer include taking on tough challenges, then I will do what I can with my intellectual capabilities for as long as I can. Writer André Malraux wrote: “A man is the sum of his actions, of what he has done, of what he can do, nothing else.” I think I still have something to contribute, so perhaps I will pursue my writing more seriously, or gain competence with my recently begun artwork, or take up my guitar again. Regardless of to what degree I’ll be able to continue my cruising adventures, I may finally be developing a sense of self-worth that is based on what I have done and what I can still do, not on what I cannot.![]()

Alex Zimmerman is a retired executive and engineering consultant who became enamored with the sea and sailing after he learned basic seamanship in the Royal Canadian Navy. From his home in Victoria, along the coast of British Columbia, he has put several thousand miles under the keels of the various small boats he has built for himself. His book, Becoming Coastal, chronicles many of those journeys. He continues to write about wooden boats and the people who build and sail them.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Excellent article.

My hope is that Mr. Zimmerman is able to enjoy many more solo voyages. As for his writing, I very much enjoyed his writing style and personal and engaging approach. I hope to read more from him in Small Boat Nation.

Best regards,

Sandy Ross

North Vancouver, B.C.

Thanks for the kind words, Sandy.

I’ll write something more for SBN when next I have something worthwhile to say.

I had A Fib for years, going in and getting a cardioversion (or shocked back into regular rhythm at the hospital. At age 75 I had an ablation which has resolved the problem. I am now over 80 and no more A Fib.

James, I’m due for an ablation, too. Just waiting for my name to come to the top of the list. I’m told the procedure has a first-time probability of success of 60-80%. I just hope I’m at the upper end of that probability curve!

Not exactly the quality of adventure Alex is used to, but the Salish 100 cruise sponsored by the NW Maritime Center is an excellent 100 mile multiday cruise in the company of like spirits and never out of reach of modern medical facilities.

Worth considering, for sure, although being from out of country I’m not sure how much I want to rely on travel medical insurance, should I actually need it, when I have a “pre-existing condition.”

Thanks, Alex for another outstanding article and your willingness to discuss your health issues and the concerns, frustrations, and emotional dissidence that accompanies such things. Your adventures always make great reading and lest I forget, your CAMUS MOON is outstanding as well. Nice work!

Steven

I appreciate your sharing your latest challenges in your adventures.

It is a reminder to those of us working towards our retirement to enjoy each day we are healthy because there are no guarantees. Health will not wait for our freedom to begin.

As a 74 year old still practicing Emergency Medicine physician, oarsman, marathoner, and cyclist I read this article with interest. Kudos for Alex’s willingness to share his personal story. I cardiovert at least one Atrial Fibrillation patient on each shift and it is very effective. When the arrhythmia returns frequently, it is time to talk to your cardiologist about an ablation, as a prior writer has mentioned. As I tell patients, nothing in medicine in 100%, but ablation seems very effective. Don’t give up those oars!! Here is a patient information sheet from Canada.

Thanks Tony. As I mentioned to James, I’m in line for an ablation and am keeping my fingers crossed that it will work for me.

Have you read “The Haywire Heart”? One of the authors is an electro-physiologist and an athlete with afib. As an emerg doc and a marathoner yourself, you would likely find it helpful.

I haven’t read it, but will put it on my list. I tell our residents and med students that after 40 years old one loses about 1% of their strength and aerobic capacity each year. Exercise won’t reverse this but might slow the rate of decline. I agree that obsessive addiction to exercise will likely cause harm. I focus more on flexibility and balance and less on strength and speed.

Tony

I hear ya. My daily stretch routine is a vital part of my day although it doesn’t get any easier.

I think an article about the CAMAS MOON would be worthwhile- although maybe not the kind of writing you had in mind. It looks to be a very practical and capable cruising boat and I’m impressed that you built that solo in 2 years. You did a beautiful job on her and I think many would be interested in her layout and construction.

Thanks Steven!

Few places in the world as striking as the BC coast, thanks for the reminder. I’ve been A fib free for 3 years following ablation after a series of meds and cardioversion, all of which were not helpful. Even the ablation failed at first but, cardioversion a few days later and all was good. Looking forward to seeing you (and CAMUS MOON) on water.

Excellent article, Alex! I’ve enjoyed following your adventures for some time, first in the WoodenBoat Forum, then your book, and now, here. I was sorry that you weren’t able to make it to the Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival with CAMAS MOON this fall, as it was my first ever time there. I wish you all the best. You are a fine example, for this 73-year-old guy, of adapting to and adjusting for the changes that come upon us as we age.

Many thanks. I wish you and yours all the best.

Thanks James, thanks Chris.

I’m looking forward to being able to get out there next season, too. In the meantime, there are a couple very minor boat projects to finish.

Alex,

I enjoyed and learned a great deal from your article. I will now look forward to reading Becoming Coastal. I am an Afib sufferer, ex-marathoner, and sailor of production fiberglass sailboats. Also, as a new discoverer of building and sailing wooden boats, I find your story inspiring. I hope to develop the skills to build and sail my boat on similar cruises.

Thank you,

James

Glad to help, James. Have fun on your boatbuilding adventures! None of us were skilled when we started. The learning journey is as rewarding as the cruising, I find.

As for finding out that all that marathoning we did might not actually have been good for us – who knew?

Alex, I appreciate your body of work around small boats. Your article on foils a few years ago is something I have gone back to several times as the best digest on the topic I find that FIRE-DRAKE comes as close to my ideal sail-and-oar cruiser as any boat I could imagine. The way you express your creativity, intellect, and awareness through boats has given me considerable enjoyment.

I am a 63-year-old male at the beginning of my dinghy cruising adventures. You have given me the benefit of your experience which I am sure will improve my self-care on the water.

Best wishes,

Paul

Paul, you’re just a young pup from my perspective! Lots of years to develop and grow your skills, confidence and experience.

Pleased that my scar tissue is of use to someone else!

Stay safe out there.

Alex, your article really resonated with me. I’ve struggled with AFIB for several years, even as I completed two R2AKs in my Montgomery 17, two Seventy48s and 1700 miles of the Pacific Crest Trail. At 74 years old, I had an ablation this summer, followed a couple of months later by a cardioversion, but I still need to take a Beta blocker to stop recurrences. The Beta blocker forces me to move much slower, but I managed to hike nine days in the Himalayas this fall with no flutter or AFIB. I know I’m done with endurance boating, which really disappoints me. I’m just struggling with whether I have enough left to hike a few hundred more miles on the PCT, at a reduced pace. The slowing down is deeply disappointing, and I didn’t really see it coming. Thanks for such an excellent article.

I hear you Bill. I’m really glad to hear that the ablation is working for you, mostly. The last significant backpacking hike I went on was 3 years ago, when the pill-in-a-pocket was still working for me. I entertain hopes of being able to do that again post-ablation, albeit likely with reduced daily distances. There are some magnificent places you really can only reach on your own two feet with a pack on your back.

It sounds like the cause of your afib might very well the same as what I suspect mine is – “exercise-induced afib” A doctor friend sent me this study that talks about the state of knowledge on it as of 5 years ago. It’s worth a read.

Alex, I loved your frank and beautifully written article and have great sympathy for the limitations your heart issues have placed upon your adventuring. I have never been the athlete that you clearly were in your younger days and my heart is fine but, at 71, I have suffered two traumatic brain injuries and find that I have lost confidence in my decision making. I enjoy puttering around the BC coast in my home-built, 14-foot, power dory but am always leery about finding myself in a situation that I can’t safely find my way out of. Like you, I am learning that writing about boating adventures is a often safer bet than actually participating in them; I’m looking forward to reading your book! I wish you many more safe boating adventures.

Murray,

Apologies for the late reply – visitors and the holiday season claimed all my attention.

Very sorry to hear about the brain injuries, but it seems to me that being leery of finding yourself in a situation that you can’t safely find your way out of is just prudence!

I hope to read some of your writing and thoughts about boating, in this venue or another. Keep us posted!