Sometimes, when you want to slide quietly from one fishing spot to the next, work up a narrow guzzle, or maneuver through a tight mooring field, it’s nice to be able to put a single oar over the stern to move the boat by sculling. The technique also comes in handy when you want to move your dinghy without getting your seat wet from the morning dew or simply do some salty stylin’ in front of a crowd of dock dwellers.

Learning how to scull takes some practice, but with the Scullmatix, a device that automatically produces the right angling of the blade, you can get your boat moving straightaway and without instruction. The Scullmatix provides benefits even for skilled scullers: It doesn’t strain your wrist, it allows you to stand in the best spot to trim the boat, and it converts one of your boat’s oars into a long, take-apart sculling oar.

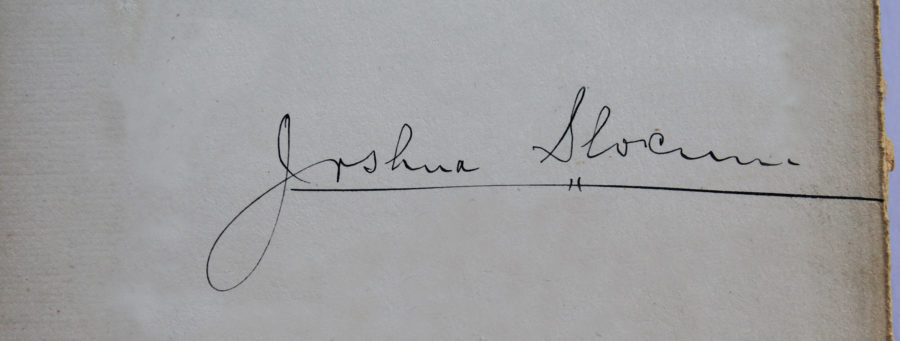

Ben Fuller

Ben FullerThe Scullmatix is made of 1/8″ stainless steel plate and secured withe a pair of stainless 5/16″ bolts and wingnuts. Resting in the boat here, it’s shown upside down.

To use the Scullmatix, clamp an oar in one side with its blade perpendicular to the device and a handle in the other. It’s sized to fit an oar with a diameter of 1¾″ and a handle with a diameter of 1½″ and a length of around 40″. The handle, situated below the oar, automatically twists the blade; you simply pull and push the handle back and forth.

I’ve been sculling for years, so I was curious to see how well the device would work and tried it on several boats. My narrow-bottomed Swampscott dory, TIPSY, was not ideal. A 7½′ oar I had kicking around was too short, even with a 48″ handle; an 8-footer, one of the dory’s regular oars, worked a little better, but I still had to stand too close to the stern. When I clamped the Scullmatix onto my 10′ sculling oar, I could sit on the after thwart; I had a good time sculling for a good half mile at 1.5 to 2 knots. The 10-footer has a 4′ blade that induces a slow and sustainable rhythm; the smaller blades meant for rowing wanted a higher “wag” rate.

Ben Fuller

Ben FullerThe author’s double ender has a short outrigger for an oarlock for sculling. It needed to be slightly elevated for the Scullmatix to keep the handle from making contact with the outrigger.

With RAN TAN, my double-ended 17′ Tony Dias–designed Harrier, I have an outrigger for sculling. With the 7½′ oar in the Scullmatix, it didn’t feel like I had enough blade in the water. The 8-footer made a difference by immersing more blade area. But what was really nice was using my 10′ sculling oar. I could put my body weight into the stroke in a nice rhythm. The boat is a little light and narrow, and it rolled when sculled hard, so the big oar would have been better with a heavier or beamier boat.

I also tried sculling an 18′ Lund outboard skiff on a windy day, using an improvised oarlock socket on a bit of wood clamped to the transom. With my 10-footer in the Scullmatix I was able, much to my surprise, to make good progress into the wind. With a wide, steady platform offered by the wide stern, there was no problem with boat trim or rocking.

The Scullmatix is designed for use with an oarlock rather than a transom notch. The flange in the middle of the device is meant to bear upon the metal lock; it will chew up wood around a notch. The oarlock socket should be oriented athwartships, and whatever the oarlock is mounted on should be relatively narrow so that neither the oar nor the Scullmatix makes contact with it.

The Scullmatix is nicely made of heavy-gauge stainless steel, and the clamping surface is long and smooth enough so that even a soft spruce oar isn’t damaged by it. The unit has wing nuts to tighten it, and securing it requires pliers or a wrench as recommended in the instructions.

The action is indeed automatic. You won’t need to grip the handle firmly to maintain pitch, or to reverse your angle on every stroke. You can push it back and forth and grip the handle only during the pull stroke; your hand can be loose, and even open, as you push. This definitely helps prevent cramping and other wrist and forearm problems. I had no trouble sculling RAN TAN a couple of miles at close to 2 knots in smooth water with little wind.

The biggest challenge is making sharp turns. With a regular sculling oar you flatten your pitch on one stroke and use plenty on the other to turn sharply. With the Scullmatix it seems almost impossible to move the oar with no pitch. Instead, I would alternate a power stroke and almost a coasting stroke to turn. With more practice I’d expect to improve.

What is really handy about the Scullmatix is the addition of a handle to make an oar long enough to scull effectively. Generally a rowing oar is too short to get its entire blade into the water and forces the user to stand too far aft in the boat or hold the oar awkwardly close to vertical. The Scullmatix would be really handy for people wanting to scull small sail-and-oar boats not equipped with with an adequate-length oar for the job. The Scullmatix, by putting virtually the entire length of an oar aft of the transom, solves the problem; a custom-length handle makes it possible to scull from a comfortable spot in the boat. If you have such a boat, I’d certainly recommend adding the Scullmatix to your equipment.![]()

Ben Fuller, curator of the Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport, Maine, has been messing about in small boats for a very long time. He is owned by a dozen or more boats ranging from an International Canoe to a faering.

The Scullmatix is available from Duckworks Boatbuilders Supply for $37.50.

Is there a product that might be useful for boatbuilding, cruising or shore-side camping that you’d like us to review? Please email your suggestions.

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.