all photographs by the author

all photographs by the authorTorqeedo’s outboards with ratings up to an equivalent of 8 hp are designed without anti-ventilation plates. The foil-sectioned shafts on all but the smallest outboard aid in keeping surface air from getting to the prop.

For decades I resisted boating under power and took pride in getting where I wanted to go under my own steam or under sail. That changed when I had kids: they were too young to help with rowing, the summer winds are usually too light for getting anywhere by sailing, and the joy of hanging out with them meant more to me than manning the oars. I built a Caledonia yawl with them in mind and installed a motor well. I bought a small 2.5-hp Yamaha outboard—a four-stroke to avoid leaving behind a cloud of stinky blue smoke typical of two-stroke outboards—but it still had an environmental impact in both the fuel it consumed and the peace it disturbed. For the past 11 years, Torqeedo has worked to eliminate both with their electric motors. In 2010 I tried the smallest motor they produce, the Ultralight, on a kayak. The equivalent of a 1-hp motor, the Ultralight would drive the kayak at an impressive 4 ¼ knots and an exciting 5 ½ knots after I added a foil-shaped fairing to the tubular shaft.

The two Travel motors are the smallest of the Torqeedo outboards. The Travel 503 is rated as the equivalent of a 1.5-hp gas motor; the Travel 1003, the equivalent of a 3-hp. I tried the Travel 1003S (S for short shaft) on three different boats: the Caledonia yawl, a Whitehall, and an Escargot canal boat. Torqeedo lists the shaft length for the Travel 1003S at 62.5 cm (24 5/8″), a measurement from the bearing surface of the mounting bracket to the center of the prop. On gas outboards the shaft length is commonly measured to the anti-ventilation plate, not the propeller axis; the Travel 1003 has no anti-ventilation plate, but I measured 46.5 cm (18 ¼″) to where one would be. That’s roughly the maximum span between the bottom of the hull and the site for the mounting bracket. The shaft length for the Travel 1003L is listed as 75cm/29.5″.)

Disassembling the motor makes it much easier to stow out of the way when it’s not needed. The long pin locks the battery pack in place.

The Travel 1003 weighs 30 lbs, 7 lbs less than my Yamaha, and it separates into three pieces—the tiller and its computer just shy of 2 lbs, the battery at 12 lbs, and the lower unit about 16 lbs—making it a whole lot easier to move around, mount, and stow.

Set in the motor well of a Caledonia yawl, the Travel 1003 S reached a maximum speed of 5 knots. The orange pin on the bench locks the shaft when the boat’s rudder is used for steering. The orange tab on the tiller is a magnetic kill switch.

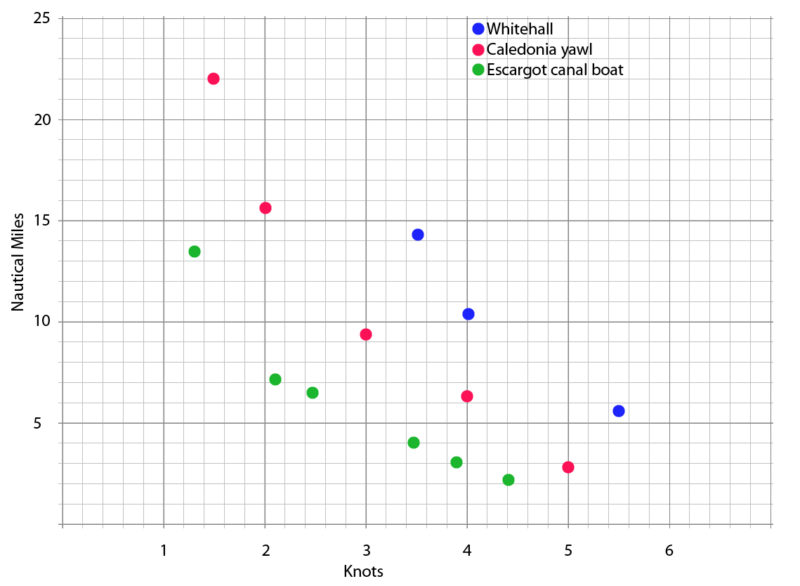

I used the Travel 1003 first on my Caledonia yawl, a 19′ 6″ x 6′ 2″ double-ender. With the motor at full throttle, the yawl peaked at 5.0 knots. My Yamaha logged a top speed of 5.8 knots. (I have an electric trolling motor rated at 40 lbs of thrust, but it falls so far short of the Travel 1003 that I don’t bother including it in these trials.) A built-in computer with GPS shows the percentage of battery charge and the distance it will take you at the speed indicated. At full speed a full charge had a cruising range of 2.4 nm. At 4 knots that range increased to 6.3 nm, at 3 knots 9.5nm, and at 2 knots 15.6 nm. The speeds and ranges I recorded were consistent with Torqeedo’s data for the Travel 1003.

Ranges predicted by the Travel 1003 for a full battery charge with three boats at various speeds

There is a slight lag in the response to the throttle, and the motor will ramp up to the selected speed rather than apply full power immediately. That keeps the boat from lurching about, and, I imagine, prolongs the life of the motor and the boat. Even with the lag and ramp-up, I was impressed with how quickly the Travel 1003 could bring the yawl from 5 knots at full speed ahead to a dead stop: just 3 seconds and less than two boat-lengths.

The Travel 1003 operates in reverse, and a latch keeps the shaft locked down to prevent the prop from climbing. The yawl made 3.5 knots with the Travel 1003 in reverse at full throttle. (The Yamaha does not have reverse but rotates through 360 degrees, as does the Travel 1003.) Releasing the latch allows the motor to kick up over obstructions while moving forward and to be raised to reduce the drag while rowing or sailing. A removable pin will lock the Travel 1003 facing straight ahead for steering with a boat’s rudder.

The Travel 1003 is quiet but not completely silent. It has a whine that rises in pitch and volume as the throttle gets cranked up, but even at its loudest it is neither an impediment to a conversation nor anywhere near as loud as my gas outboard. It doesn’t vibrate either, so there’s no rattling anywhere on the boat. Its relatively quiet operation at low-to-moderate speeds is great for dinner cruises. I’m used to gauging speed by the racket my gas motor makes when moving along at a good clip, but even at full throttle, the sound the Travel 1003 makes belies how fast the boat is moving; it’s more like sailing than motoring.

On my 14′ lapstrake Whitehall the Travel 1003 peaked at 5.5 knots. (I didn’t—and wouldn’t—try to mount the heavier Yamaha on the transom—there’s little buoyancy in the stern.) I also did trials with my son’s 19′ 6″ x 6′ Escargot canal boat, weighing over a half ton with gear and two of us aboard. It brought the canal boat up to 4.4 knots, just slightly slower than the Yamaha at 4.7 knots.

Torqueedo claims on its website that the Travel 1003 “can do everything a 3-hp petrol outboard can, plus it’s environmentally friendlier, quieter, lighter, and more convenient.” The latter half of that is certainly true, but I’d suggest the former isn’t a good comparison to make. According to the owner’s manual, my Yamaha has a maximum output of 2.5 horsepower or 1.8 kW at 5,500 rpm, while the Travel 1003 display reads 1,000 watts (1.0 kW) at full throttle with maximum propeller speed listed by Torqeedo at 1,200 rpm. Going by the numbers gets murky. The Yamaha rating is for propeller-shaft horsepower, and the Torqeedo rating is for input power with propulsive power at 480 watts; static thrust is listed as 68 lbs, but that’s not calculated the same way as it is for trolling motors. Torqeedo offers some clarification on the terms and their equivalence with gas outboards, but my sea trials for top speed didn’t bear that out for the Travel 1003, even up against a 2.5-hp instead of a 3-hp gas outboard.

I haven’t made precise mileage calculations for my gas outboard, but one measurement I made on Google Earth for a passage on a full tank of gas (0.24 gallon) was 6 miles, running at about two-thirds throttle. That’s 25 miles per gallon. At a comparable speed the Travel 1003 will cover about the same distance. To extend the range of my gas outboard, I’ll carry two 2.5-gallon gas cans for a range of 125 miles. For the Travel 1003, an extra battery, at $650, brings the range to 16 miles. For charging away from home, Torqeedo offers a 50-watt solar charger for the Travel 1003, and it is possible to recharge its battery from an in-board 12-volt system. In my experience recharging was an overnight process, only slightly more than the 14 hours listed by Torqeedo; the latest models have cut that time in half. While I don’t have to think much about my range with my gas outboard, the Travel 1003 would require some thoughtful planning to achieve the same range for an extended cruise. If your outings with the Travel 1003 aren’t pushing the limits of its range, you can use the energy for other purposes: its battery has a port you can use to charge electronic devices.

While Torqeedo notes that the Travel 1003 is the equivalent of a 3-hp gas motor, focusing only on range and maximum speed is to overlook their product’s best features and to suggest poorly suited applications. My gas outboard allows me to take five-day island-hopping cruises, but I don’t take it on the vast majority of my outings. For day trips I’m content to row, paddle, or sail short distances in peace and quiet, and with the Travel 1003 I’d be tempted to motor too. I enjoy taking friends and family out on the water for dinners, but my Yamaha is noisy and its fuel messy and smelly; it would be great to be underway with the Travel 1003 during the evening when the sun sets and the city lights come on. I don’t fish, but having an electric motor with the oomph to get to the fishing hole and the quiet operation for trolling would be a boon. I’d also feel much better knowing that my boating under power didn’t add to the burden borne by the waters that carry me and by the air that I breathe. To that end, the Travel 1003 has the clear advantage.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Monthly.

Torqeedo distributes its products through a network of dealers and offers the Travel 1003 for $1,999 with a two-year warrantee.

Thanks to reader Elliot Arons for suggesting this review.

I have had Torqeedo Travel 1003 for several years. It has a strong battery and will push my Norseboat 17.5 for about 10 miles at 3.0 knots. As you say, it is not a good choice for extended multi-day trips where recharging may be difficult, but for a day trip or overnight it’s great.

Aside from the advantages you mention, there is no winterizing, spark plugs to foul, or fuel to spill. Best of all it starts with a twist of the throttle. I feel confident sending my kids or friends out without worrying about their ability to get a gas motor running.

The only drawback, as you point out, is the range, which I bet most of us never exceed anyway. The advantages are far more persuasive to me. If everyone was already using Torqeedos and the gas outboard was introduced as an alternative, I bet very few people would by one.

We have a 1003 that we use on our 28′ Stuart Knockabout which displaces 4,000 lbs. We have a removable side bracket made of very heavy stainless. We had 4-hp Yamaha 4-stroke on it for years and you you could go straight to full throttle. First time we tried that with the 1003, the incredible torque cracked the bracket! After we had it rewelded, we now accelerate slowly and never go to full throttle until the boat has some way on her. Full throttle is just shy of 5 knots and we usually run at 3 if the wind dies. Great motor! I only wish the tiller display was easier to read without glasses!

It should be noted that, unlike a gas motor, the Torqeedo must be removed when sailing. According to the manufacturer, it can not be freewheeled without damage to the motor. This is a pain, especially when one wants to go just a short distance before switching to sail. The motor must be taken off and stowed before sailing. I never worry about drag on my Caledonia, so I would rather leave the motor in the well, but it’s a no-go.

From the manual for the Travel 1003: “Do not leave the motor in the water when the boat is moved by other drives (e.g. while sailing, towing the boat) to prevent damage to the electronics.”

During my trials with the Travel 1003 I could hear the motor freewheeling if I turned throttle to the off position and the boat still had some way on. Those very brief periods of freewheeling didn’t have any evident effect on the electronics, but longer periods may well do damage.

Any outboard left in the water is going to create a significant amount of drag, so there is a good return on the investment of stowing it. The Travel requires some fiddling with the wiring to disconnect the tiller, battery, and motor, but then those three pieces can be removed and stowed separately, a much easier task than pulling a gas outboard out and stowing it.

A friend of mine sailed his Caledonia yawl with his gas outboard remaining in the well and had nothing to plug the well even if he chose remove the motor. On the one occasion I had to sail his boat (without him), I initially left the motor in place. At first I couldn’t understand why his CY was so much slower than mine, but I soon realized the motor must be creating some drag. When I removed it the boat picked up some speed but there was a lot of water sloshing up from the well. I stuffed a couple of PFDs in the well to keep the water out of the boat and to fill the gap it makes in the underwater surface of the hull. The boat then took off and felt as fast and as lively as my CY. I’d guess his boat had its speed cut by at least a quarter with the motor in place.

I’ve outfitted my CY with an insert to fill the well when it is not in use. The bottom of this little “box” lies fair with the hull and has a 1/4″-thick plexiglas window that comes in very hand when I’m sailing shallow water and need a clear view of the bottom.

Question: Can the Torqeedo tilt up out of water if mounted on a transom?

Yes, the Torqeedo Travel can be tilted up out of the water just like any small outboard motor, so you can raise it for sailing, rowing, or coming ashore without having to remove it from the transom.

Thanks for the well done article on the Torqeedo Travel 1003. I was sad to hear of the sudden “delivery” of your Torqeedo into 25′ of water! On our SolarSkiff(patent-pending), which exclusively uses the Torqeedo Travel 1003 as its motor, we have come up with a solution that prevents the problem you encountered. I drill a 1/4″ x 4″x 8″ sheet of King Starboard (a high-density polyethylene sheet available from boat outfitters) with 2 circular holes slightly bigger than the Torqeedo motor-mount screw pads, and attach this plate to the transom with stainless-steel screws, washers, and acorn nuts for a nice finish. Then I place my motor on the transom, screw the pads into the circles and against the transom so that the motor is locked in place and not going anywhere. Even if the screw pads become loose, the motor will stay locked in place by the 1/4″ depth of this added plate.

In the early development of the SolarSkiff, I had a trolling motor come loose from the smooth HDPE plate I was using for the transom. I did not lose the motor altogether, but the sight of the motor veering up sideways is scary enough. This little plate with a couple of circles drilled in it for the motor screw pads solves the problem in style. Of course, the same kind of plate could be built in wood to keep a wooden boat all wood.

As a Torqeedo dealer and user on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, let me offer a clarification about the Travel 1003’s horsepower. The motor has a power consumption of 1000 watts at top speed, which is equal only to about 1 1/3 hp. While this keeps power consumption low, it also keeps the motor under 2 hp, which is useful for boats like the SolarSkiff that are designed following the US Coast Guard standards for watercraft with engines under 2 hp. However, Torqeedo claims a propulsive force equivalent to that of a 3 to 4 hp gas engine: its electric motor is more efficient at converting its 1000 watt input power into propulsive output power, hence the 3-4 hp “equivalency.”

My wife and I had a chance to put this power claim to the test this summer. We crossed the Bay of St. Louis in a two-person SolarSkiff for a group picnic at some friends’ home across the Bay. Going over in the late morning, the winds were light. Coming back, however, the afternoon seabreeze predictably began to fill in and it wasn’t long before we were motoring back against 12-knot winds, gusting to 15, with whitecaps everywhere. The Torqeedo Travel 1003 had the power to keep us moving against the wind and waves with no problem: we can’t do that with a 55 lb-thrust trolling motor! While I can honestly say that 12-mph winds are about the top that I would plan to be out on the water in a small craft with a Torqeedo, it both had the power and the range we needed that day for the 6-1/2 mile round trip. I did take my Torqeedo battery charger in my dry bag, though, and plugged the battery in while we enjoyed lunch with our friends, just to make sure we had sufficient power for the return home.

The most I have run my battery down is to 20% of its maximum capacity, with the motor conveniently and automatically beeping reminder warnings when it hits 30%, 20%, and 10% capacity. With the new lithium-ion battery design, it fully recharged in only 5 hours. The 7-hour recharge with the new battery is for a recharge of a fully discharged battery, whether plug-in or solar.

A friend who uses his Torqeedo Travel 1003 to power his Ensign sailboat with its heavy keel in and out of the harbor feels that a 4 hp equivalency claim is fair, comparing how his boat goes now with the Torqeedo to its performance with his previous gas engine. He does pull the motor up out of the water when under sail to prevent drag as well as the kind of freewheeling damage mentioned in the article.

Bottom line: the Torqeedo has the power and range to support a fun day out on protected inland waterways, but requires both advance trip planning and monitoring the on-board display on the tiller to make sure you have power to spare when you get back to port.

You can see our one-person SolarSkiff running with the Torqeedo Travel 1003 on our web site, the SolarSkiff You Tube channel, or the SolarSkiff Facebook page.

Chris,

Congrats on the outstanding, detailed piece on the Torqeedo and the performance comparison to your Yamaha. I believe the current Torqeedo is a breakthrough product. I broke a long-time promise to myself never to sell my 5-hp 2-stroke Johnson. But, at long last, its 46-lb weight had become too much; its occasional hard-starting caused by water in that miserable fuel known as ethanol had become discouraging, as had the endless pulls on the starter cord.

There is little to add to your piece but the following may also be of help to those considering purchase of a Torqeedo. In your photo of the disassembled motor, there is a small orange peg shown beside the larger orange rod used to secure the battery to the motor. Although I have not found mention of it in the owner’s manual, the orange peg is meant to be inserted through a hole in the motor’s top portion into a hole in the leg. It prevents the head from rotating so the motor can’t be turned as accidentally happened to you when you least needed it. This would be of most use in an application where the boat’s rudder is there to steer with. It would not be practical on the transom of a rowboat where rotating the motor is needed for steering.

Oddly, I recall reading an owner review of the Torqeedo in which he complained that the mounting screws loosened up and his motor fell off. For whatever reason, this may be something owners should check before every outing to ensure things are really, really tight. It was good of you to note there are holes in the clamp handles by which they may be secured to the boat. The owner’s manual should mention this aspect. In my own application on the transom of an inflatable, I have one of those locking devices that slides over the clamping screw handles and effectively prevents them from loosening in any threatening manner. I can imagine your experience was quite unnerving.

As a motor for an inflatable or dinghy to get one from dock to mooring and back, the Torqeedo is perfect. I have found that full-throttle operation for about 25-30 minutes takes the battery down to about 62% but recharging at home has the battery back to full charge in rather little time. When I had the chance to use the Torqeedo 1003 longshaft as a sailboat auxiliary, I found that it easily moved a 3100-lb keel daysailer when the wind died. Putting it on the side bracket was a relative pleasure because, when broken down into its three main components, weight is not an issue. (I have tied a line from the battery to the battery mount rod so the latter can’t be lost overboard.) About 15-20 minutes running at part throttle brought us back to the mooring. Again, recharging was quickly done at home. The key for such an application, as the Stuart Knockabout owner noted, is the motor’s torque. I believe an electric motor develops peak torque at 0 rpm and that is key to getting a boat moving and then keeping it going steadily. But speed should not be a priority.

After one season, about the only improvements I can think of would be larger numbers on the readout display, a less abrupt response to initial throttle input—new owners should practice gingerly when first starting out if in a slip—and a somewhat greater tilt angle to get the skeg completely out of the water. The absence of need to winterize, let alone worry about storing or discarding fuel, are obvious plusses.

The 1003 is about twice the $900 price listed by West Marine for a Mercury 3.5 hp. If one has the right application need, I’d say the Torqeedo is well worth it.

Thanks for your comments, Stan. The small steering fixing pin is mentioned in the Travel 1003 manual on pages 9, 15, and 26 (do a search for “pin”), but there isn’t an illustration that shows it clearly. The pin gets put in place before the battery and once the battery is locked with the large locking pin, the small pin is secured.

I have an Able, a Selway Fisher design, in which I have a permanently installed 6-hp Tohatsu outboard. The engine is mounted on the centerline in way of the keel and I leave it down (in neutral) when sailing. Being in the draft of the keel the drag seems to be minimal. I would like to replace this with a powerpod of some sort, faired into the keel. I was considering a Torqueedo 1003 which I would use the power head and the controller. I did note that the Torqueedo manual says not to leave the unit freewheeling in the water when sailing as there would be damage to the electronics of the system. I am assuming that this is because, when free wheeling, the motor becomes a generator, sending an electrical charge back into the system.

If this is the case, would: A: diodes (to negate electrical feedback) solve this problem? B: A mechanical stop on the prop? C: A master switch to disconnect the power from the power head?

I think that there are many of us out here looking for a way to modify existing trolling motors to power our small craft. Spending $6,000.00 on an Elco pod is out of reach for most of us.

I belong to the TSCA here on Cape Cod and this is a topic of conversation quite frequently. Many freshwater reservoirs and lakes are off limits to gas engines, so this would open up sailing venues for a lot of us.

I’d love some feedback on this.