Just last year I was hoping to write an article very much like Mark Kaufman’s on making custom hardware, and the approach I had in mind was to make the process and the equipment required more accessible. I happen to have acetylene torches, but they’re expensive and not common equipment in the workshops of amateur boatbuilders. I was hoping ordinary propane torches would provide the heat required for using the silver solder I’d been using for years. Silver solder, like the 45% silver brazing alloy Mark uses, creates a very strong and long-lasting bond and is easy to use. I tried using a single propane torch to solder two short pieces of 1/4″ x 1″ brass bar together without success, then I used two torches, and then two torches with the brass surrounded with fire bricks to retain the heat. I couldn’t get it hot enough to melt the solder and I gave up on writing the article.

photographs and video by the author

photographs and video by the authorThe yellow trigger turns the gas on and ignites it. Turning it clockwise a quarter turn locks it in the off position and depressing the silver-colored button above it locks it in the “on” position. The black knob on the opposite side controls the flow rate of the fuel.

When Mark’s article arrived, I was inspired to give it another try. I reread Harry Bryan’s article, “Silver Soldering: A straightforward technique for joining metals,” in WoodenBoat’s July/August 2010 issue. I followed his advice and bought Bernzomatic’s TS 8000 torch with a canister of MAP gas. (The article also mentioned Bernzomatic’s TS 4000—a similar torch without the trigger and at a lower cost, but it doesn’t deliver as much heat.)

The TS 8000 has some very nice features that are a great improvement over my ordinary propane torches. A finger trigger starts the gas flowing and ignites it with a piezo-electric spark. Releasing the trigger stops the flow of gas, extinguishing the flame. That’s safer and less wasteful than a propane torch, which has a valve to control the flow of gas. The TS 8000 has a valve for adjusting the rate of flow, but you don’t need to turn it to light or extinguish the flame. The trigger has a safety lock to prevent the torch from being turned on either inadvertently or by curious young hands. The trigger also has a “run-lock” button to keep the torch operating without having to keep your finger on the trigger. The cast-aluminum body of the torch provides a comfortable grip that’s more secure than holding a gas cylinder.

The TS 8000 will burn both propane and MAP-Pro gas (propylene)—the cylinders for both have the same threads. Propane burns at 3,600° (all temperatures in Fahrenheit) and MAP-Pro at 3,730°, just 3.6% hotter [This calculation of percentage isn’t appropriate. See Comments below. Ed.]. (Acetylene with oxygen, by the way, burns at 5,800° to 6,300°.) I have three grades of silver solder with different melting points: Hard at 1,425°, Medium at 1,390°, Easy at 1,325°. With those numbers, it seemed to me that a propane torch would have been adequate for silver soldering, but it’s not the temperature of the flame that makes silver solder melt and flow into a joint, it’s the temperature of the metal. While the flame is heating the workpiece, the workpiece is absorbing some heat but losing some to radiation, conduction, and convection. To get to the temperature at which a solder will flow, the torch has to deliver heat at a rate that exceeds that of the heat loss.

The TS 8000 delivers that heat. While the opening at the tip is about the same size as that of a small propane torch, the TS 8000 has a much larger flame. It’s also louder and the grip becomes very cold, both indications that it consumes fuel faster and delivers more heat.

Even with propane, the TS 8000 did very well with silver soldering. I could get a 1″ square of 1/4″ brass silver-soldered to a 5″ length of the same material using hard solder. That’s the cooler flame working the highest-temperature solder on a workpiece larger than what I usually make.

I did another test, heating 1″ lengths of 1/4″ copper rod. With a propane torch, the copper came up to a dull glow and maintained its shape with no signs of melting. The TS 8000, burning propane, melted the copper until it turned into a ball, and, when burning MAP-Pro, it turned the copper into a ball that must have been less viscous because it rolled off the fire brick.

After reading Mark’s article I bought some Safety-Silv 45. It has a solidus temperature (below which it is solid) of 1,225° and a liquidus point (above which it is liquid) of 1,370°. Acetylene with oxygen burns at 5,800° to 6,300°. I was pleasantly surprised to see the Stay-Silv flow quickly into the joint between two pieces of brass bar and then built up a fillet as I fed more of the brazing alloy into the joint. Capillary action pulled the liquid alloy up the sides of the vertical piece. I’ll be switching from silver solder to Safety-Silv 45 for my future boat-hardware projects.

I’ve been impressed with the features and the performance of the Bernzomatic TS 8000. It will do a wide range of projects that fall between a propane torch and an oxy-acetylene torch, and for most of my projects I’ll be able to use it with propane at one-third the cost of MAP-Pro gas.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Monthly.

The Bernzomatic TS 8000 is available at many hardware stores and home-improvement centers and from online retailers. The torch alone can be purchased for about $45, or as a kit with a canister of MAP-Pro gas for about $55.

Some tips on silver soldering

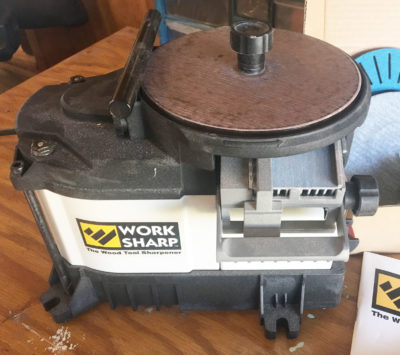

The materials for silver soldering include silver-solder wire, a firebrick for a work surface, paste flux, and a torch. Here the TS 8000 is attached to a propane 1-lb bottle, the kind I use for some of my camp stoves. The more slender 14.1-oz propane bottles also work. The firebrick is very soft and it’s quite easy to saw of a bit of one end to serve as a backstop to reflect heat back to the work piece.

With the areas to be soldered well coated in flux, these pieces of brass are ready to be soldered. I use cross-locking tweezers on a third-hand base to hold parts—as flux melts, pieces tend to shift if they’re not kept in place.

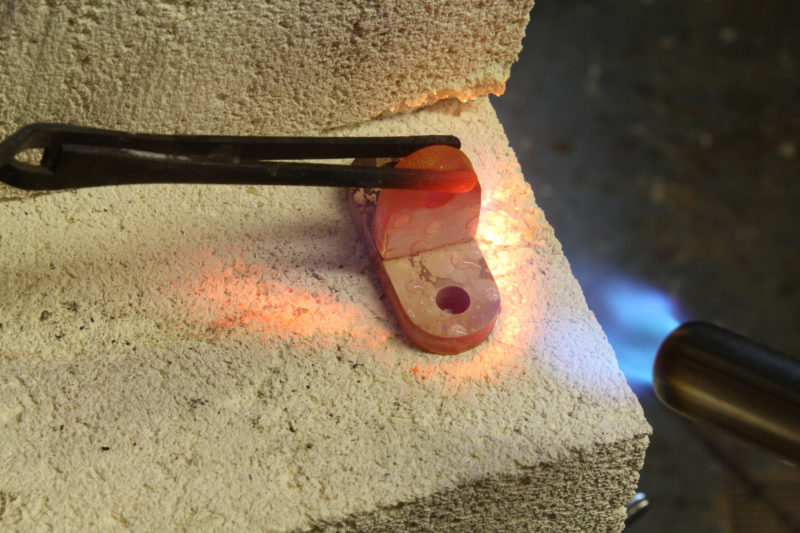

When heating the parts to be soldered, the smaller piece will heat up faster, so aim the flame at the larger piece. When the metal is heated red-hot, it radiates a lot of infra-red rays, and it’s important to wear protective eyewear with a Shade 3 rating to block the infra-red and serve as safety glasses. A respirator is also required. The flux here has melted and looks like water drops. The tip of the solder wire will melt quickly when touched to the metal and flow into the joint between the pieces of brass.

This cooled gudgeon needs cleaning to remove glassy flux and black scale.

Rather than sand the newly soldered piece, you can use a pickling bath to remove the flux residue and black scale. The commercial product I used to use was probably sulfuric acid; lately I’ve been trying a less noxious bath. It’s 1 cup of white vinegar, a tablespoon of salt, and 1/2 cup of hydrogen peroxide. I use a Pyrex bowl and microwave the solution before using it, stopping shy of boiling. While the bath is not quite as effective as what I’d been using, it does make a good start on cleaning up after soldering or brazing.

This is a test piece of brass after soldering.

And this is after soaking in the pickling bath. The flux residue is gone and much of the blackened brass has been removed.

With a bit of sanding and buffing the new gudgeon is ready to go to work. Sanding with 220-grit and higher leaves an acceptable finish, but I like to use a cotton buffing wheel charged with emery for the finishing touches. It gives the metal a nice soft feel.

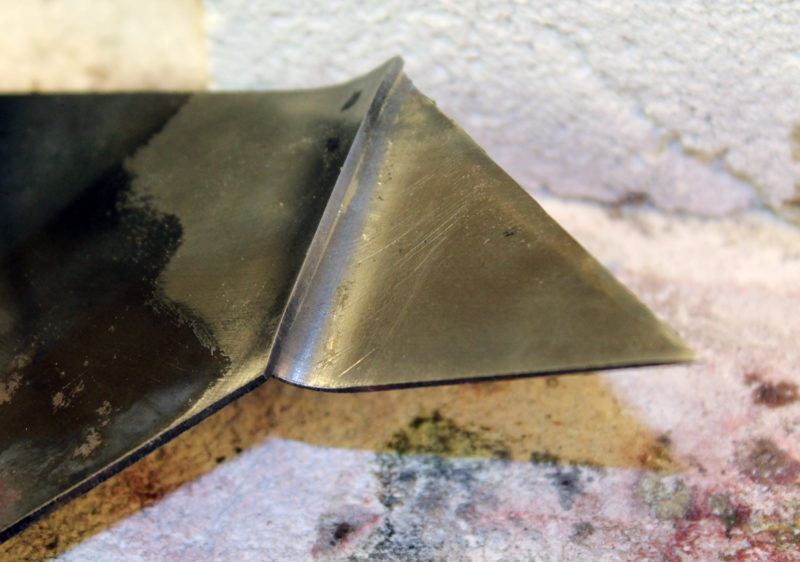

I hadn’t used silver solder on steel, so I thought I’d give it a try using the same flux, solder, and torch on a scrap of the 1/16″ sheet steel I used for my wood stoves. The result, shown here cleaned and polished, looked great.

To test the strength of the solder, I put the triangular piece of steel in a vice and used the other piece to pry the right-angle joint open. The silver solder held with no signs of failure.

Is there a product that might be useful for boatbuilding, cruising or shore-side camping that you’d like us to review? Please email your suggestions.

Thank you for the nice article; I’ll be getting one of these torches for sure. A curmudgeonly comment from a physicist: 3730° F is not 3.6% hotter than 3600° F. Temperature doesn’t work that way; it’s not a unit of heat and does not scale linearly The difference of 130 F° is fairly significant (F° is the notation for Fahrenheit temperature differential) and is equivalent to the difference between 0°F and 130°F. (An example: you might intuitively think that 20° F is twice as warm as 10° F, but if you express the same temperatures in degrees Kelvin, describing exactly the same environmental conditions, you get 261° K and 266° K, which scales (inappropriately) to a 1.9% difference.)

You are very correct in inferring that this torch is more effective because it delivers more heat by burning more fuel.

I appreciate the correction. I can see the problem with the math and the various temperature scales. It’s about 64°F here in my office, which I would have expressed as twice as hot as freezing, 32°F, but with the same temperatures expressed in Celsius, 17.7°C is clearly not twice 0°.

A nice article, with some helpful suggestions. About ten years ago, I built pintles and gudgeons for my MacGregor sailing canoe. I can’t remember what material I used, it might have been bronze but more likely it was naval brass. In any case, I used the same tools, a TS-8000 with MAP gas and Safety-Silv 45. I had no experience with brazing of any kind, but found the job pretty straightforward, apart from heating the brass so much that it started to sag as though it was made of butter. I did learn in the process how important it is to support everything thoroughly and to apply the brazing wire sparingly.