There is no such thing as a short conversation with Tom Wylie. A ten-minute conversation with the yacht designer will last an hour and a half and will range from sail airflow to carbon-fiber mast construction. Along the way, the conversation will drift past the economics of small boats, touch upon the maximum curvature of the bilge that is consistent with laminated frames, and linger on his passion for ocean conservation.

On this day in September 2010, Wylie is describing the design considerations behind the Spaulding 16, a boat originally sketched by Myron Spaulding in 1923 but reinterpreted by Wylie in collaboration with naval architect Doug Frolich. The new design is not only a tribute to Spaulding, one of the San Francisco Bay Area’s premier yachtsmen, boatbuilders, and sailors, but also the signature craft of the youth boatbuilding program at the Spaulding Wooden Boat Center in Sausalito, California.

The design brief called for a boat that would be moderately challenging to build, fun to sail for both experienced and less-experienced sailors, and a good boat to introduce neophytes to the sport. It would introduce 10- to 18-year-olds to Spaulding’s boats and the history of wooden boat building in Sausalito.

Craig Southard/Spaulding Wooden Boat Center

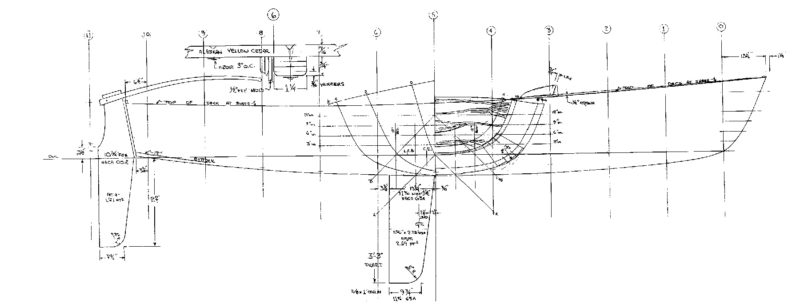

Craig Southard/Spaulding Wooden Boat CenterIn keeping with the mission of the Spaulding Wooden Boat Center, the Spaulding 16 was built with traditional lapstrake planking of Alaska yellow cedar, fastened over laminated frames of the same species.

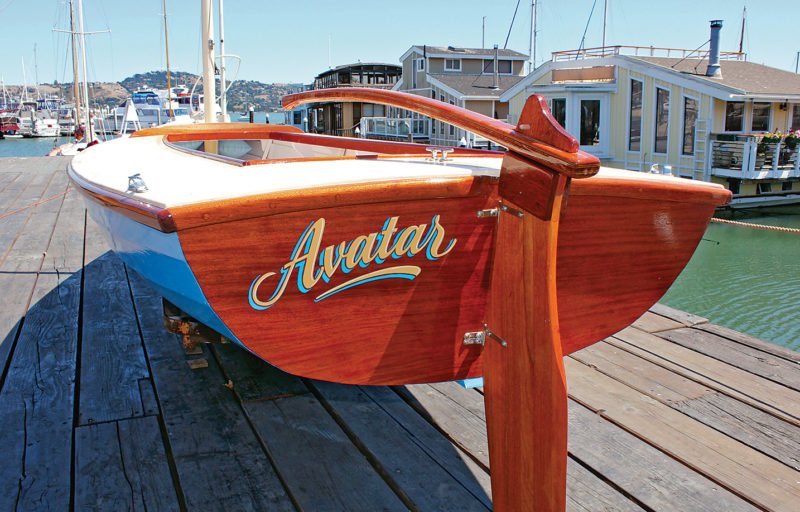

As the first Spaulding 16, AVATAR, hangs from a crane in anticipation of its official launching, Wylie tells me about turning a simple drawing into a boat. “We aren’t really sure what Myron intended, so I had to improvise. There is no way that sheer is Myron’s sheer, but I think I have captured the spirit of the boat that Myron was sketching.”

As we are speaking, Andrea Rey, the Associate Director of the Spaulding Center, starts the official launching ceremony for AVATAR, built by 25 teenaged apprentices over the course of 12 months. This was not the first boat built in the youth boatbuilding program, but it is by far the most complicated. The round-bilged, lapstrake-planked hull provided the challenges of shaping the curved stem and carving the rabbet, spiling planks, cutting “gains” at the ends so that the planks meet flush at the stem, and fitting deckbeams and carlins to support the deck.

I study the sheer as the boat is lowered into the water. I do not know much about Spaulding’s work, but it looks like a Wylie boat to me. The boat floats high in the water, and it looks fast with its carbon-fiber mast and the square-headed mainsail. Wylie is known throughout the West Coast and the world for designing high-performance sailboats that are fast and handle well, and AVATAR is no exception. Wylie started his long career in boatbuilding and design as an apprentice under Spaulding himself, and to this day he has the same restless inquisitiveness and willingness to try new things that Spaulding was known for. Some of his designs, most notably RAGE, which was built by Steve Rander in Portland, Oregon, and set records for California-to-Hawaii Transpac races in the 1990s, are cold-molded. However, he has enthusiastically pursued composites in his yacht construction, so the Spaulding 16 represents a nod to his roots at Myron Spaulding’s boatyard.

Craig Southard/Spaulding Wooden Boat Center

Craig Southard/Spaulding Wooden Boat CenterStudents in the Spaulding Center’s youth boatbuilding program built the prototype Spaulding 16, which they christened AVATAR. The boat was launched in 2012.

Seeming larger than her 16′, the Spaulding 16 has seating on the side decks or on the floorboards. A single thwart straddles the daggerboard trunk. Because of its beam and high freeboard, its single rowing station will require long oars and tall oarlocks. A single scull mounted on the aft deck might be a reasonable alternative.

The boat weighs about 350 lbs and was designed to float on its lines with 450 lbs of crew weight and gear. The relatively slack bilges make the hull initially tender, although it stiffens up as it heels. Sailed light, she will reward experienced sailors with a fast and exciting ride. But to make her more forgiving for education and training, which are central to the Spaulding Center’s mission, ballast may be necessary. Wylie is examining water bags or a weighted daggerboard to add ballast without permanently altering the boat’s sports-car-like performance.

AVATAR was built of 7⁄16-inch-thick Alaska yellow cedar planking screwed to laminated frames. The plank laps are fastened with copper rivets backed up with a bead of poly-sulfide caulking. Plywood was used for the transom and decks to simplify construction and prevent leaks. The daggerboard and the rudder were traditionally fashioned from solid wood, edge-glued and drift-bolted.

Two decisions made early in the building process came back to haunt the builders. The first was to cut out full-sized paper templates rather than lofting the boat, and the other was to use eight strakes per side instead of ten. Jim Labidoa, a cabinetmaker and adult volunteer, said the apprentices had to engage in a full-scale wrestling match to get the paper half-templates to lie flat and true while their outlines were traced onto plywood mold stock. Making them symmetrical proved nearly impossible. I had to laugh as Jim was waving his arms and describing the unruly templates, because I have had the same experience myself, which is why I now loft every boat I build.

Reducing the number of strakes made each of them less flexible than the narrower ones would have been, and as a result the planks would not lie flush to the mold at station No. 1 forward. Craig Southerd, the Youth Program Director, noted that the crew broke several planks trying to fit them to the slender bow. Lofting could have exposed this problem earlier. As it is, the boat is a little fuller in the bow than the plans call for, but nevertheless the plank lines are fair and the shape of the bow blends in beautifully with the rest of the boat.

Traditional materials and techniques fit the Spaulding Center’s mission. But if I were to build this boat, I would likely strip-plank or cold-mold the hull and sheathe it in fiberglass so it would be light and perpetually tight. A few broken strips during construction would not be a financial burden.

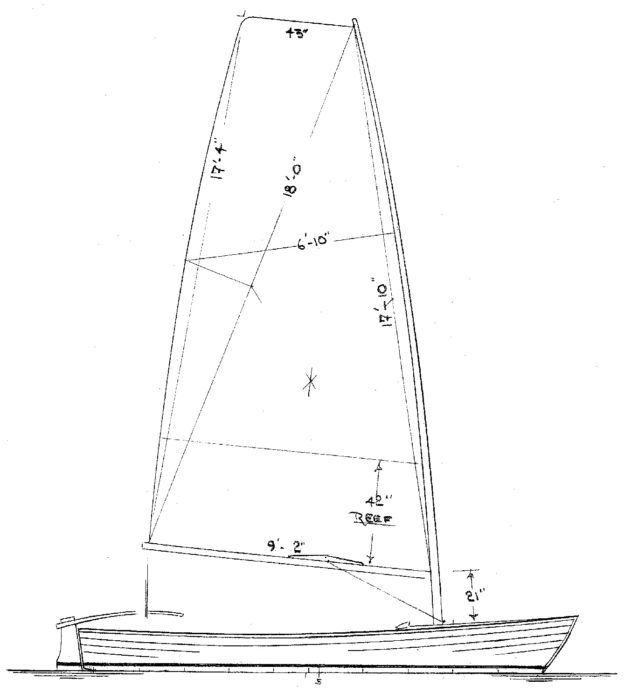

The carbon-fiber mast and the square-headed rig, though not traditional, are in keeping with Wylie’s thinking about rigs. The sail is controlled by a single sheet and is easily reefed. These are important elements for a sail-training boat that will also take some Spaulding Center visitors daysailing. The slender, unstayed mast is designed to bend off to leeward in puffs, spilling wind to keep the boat on its feet. The square-headed rig carries quite a bit of sail, 111 sq ft, with a single halyard on a relatively short mast. Reefed, the sail is 80 sq ft. The mast is made of the top of a windsurfer mast joined to a custom-made carbon tube. A wooden mast would work, but at the cost of additional weight aloft. At the foot of the sail, where weight is not as critical, wood is used for the boom.

Craig Southard/Spaulding Wooden Boat Center

Craig Southard/Spaulding Wooden Boat CenterAVATAR is a handsome addition to the Sausalito waterfront, bringing Myron Spaulding’s youthful vision into life and providing an exciting sailing option for the Spaulding Wooden Boat Center.

Rides were hard to come by on launching day, so I had to content myself with secondhand performance reports. Craig Southerd, smiling broadly, said that on the first sail, the boat planed out of the harbor with two people aboard and a reef in the main in 15 knots of wind. The sailors were Gordie Nash, a Bay Area boatbuilder and one of the best racing sailors on the Bay, and Frolich, the architect and an accomplished sailor in his own right. “It’s typical of a Tom Wylie boat: lively, easily balanced with a light helm, quick to tack, and responsive in fluky winds that ranged from 10 to 25 knots,” Frolich said. Even with two aboard, he would not have added ballast. “This boat is really fun to sail. Extra weight would just slow it down. I wouldn’t hesitate to take my wife and two young children out on day sail around Angel Island right now. That would be a great ride!”

The Spaulding 16 would be a challenge to build but would reward the careful builder with an exciting boat that will be a delight to sail. Although building times are highly variable, I estimate that 1,100 hours would be required to build a cold-molded version, which is a substantial investment of time and effort. But very few of Wylie’s designs are suitable for an amateur builder, and the Spaulding 16 might very well be the quickest and least-cost way to get into a Wylie-designed boat. Also, the Spaulding Center can build completed boats for paying clients in traditional, cold-molded, or strip-construction.

As I watch AVATAR sail out of the harbor with the first group of young apprentices aboard, I am impressed by the way the boat slides through the water, even with five people aboard. I hear nervous laughter from a couple of students who helped build the boat but have never been sailing. AVATAR is a tangible tribute to Myron Spaulding, the realization of a project begun in 1923. But an even greater tribute is the way this little craft has united four generations of Bay Area boatbuilders. It is an impressive piece of work, and the students are justifiably proud. John McCormack, the lead instructor on the project, summed it up best: “The kids did a really fine job.”![]()

The Spaulding Wooden Boat Center no longer offers plans or finished boats for the Spaulding 16. The review is presented here as archival material.

The Spaulding 16 design builds on a sketch that Myron Spaulding drew, and her traditional plank-on-frame construction pays homage to the legendary Sausalito designer’s aesthetics. At the same time, especially with its square-headed, unstayed rig, designer Tom Wylie brought a modern sensibility to the design, something that Spaulding himself may well have appreciated in a boat by—and for—youthful sailors.

Spaulding 16 Particulars: LOA 16’3″, LWL 14’7″, Beam 5’6″, Draft (board up) 6′, (board down) 3’3″, Sail area 111 sq ft, Weight 350 lbs

Are plans and offsets available? It’s a beautiful little boat.

The Spaulding Wooden Boat Center no longer offers plans or finished boats for the Spaulding 16. The review is presented here as archival material.

—Ed.