It was 5 a.m. and Thor Belle and I were late. The first beams of light were already slicing through the clouds of a gray Washington morning as the crunch of gravel under our truck tires marked our arrival to the Port Townsend boat launch. When we stepped out of the truck, we heard halyards smacking masts in the adjacent harbor. Just offshore, sailboats tacked back and forth behind the starting line like greyhounds nervous to leap onto the racetrack.

For days, there had been speculation about what the early-June weather would do, and big conditions seemed likely. Most of the teams gathered here for the 2019 Race to Alaska (R2AK) were already on the water, and only a handful of smaller craft like ours were still in the final preparations to launch. The pier next to the Northwest Maritime Center was crowded with spectators and race-tracker junkies who had turned out to support the 50-odd teams of crazies. The race, on paper, is straightforward enough: Navigate a boat without a motor and with no outside support from Port Townsend, Washington, to Ketchikan, Alaska. Simple, right?

Photographs by and courtesy of Thor Belle

Photographs by and courtesy of Thor BelleThe dory, LOOK FAR, was built in 1978 in Anacortes, Washington, by David Jackson of Freya Boatworks. David, now a marine surveyor, says he built the Hammond 16′ Swampscott dory to plans in the Dory Book, but with a few tweaks. Thor, pictured here, found the boat in the bushes down by the Columbia River, where it had been sitting for the last ten years or so, half-heartedly covered and just waiting for some fools to come along and give it a second life. The owner agreed to sell it to Thor for a dollar after hearing a long story about wanting to raise money to help the ocean by restoring an old wooden boat and going on a crazy adventure with it. The hull had two major cracks, one of which had been repaired with chopsticks, dental floss, and spray foam.

Two of our most loyal supporters, Emiliano and Sue, came to see me and Thor off. After a rushed greeting, they ceremoniously circled our Swampscott dory, LOOK FAR, singing blessings and adorning her with feathers and sprigs of cedar. Emiliano had sewn the original sails for LOOK FAR when she was built in 1978 and, as an avid dory lover himself, was fully invested in our success. The Soviet National Anthem, the official starting “gun,” suddenly rang out over the race organizers’ PA system, and the race was on.

As the fleet charged across the starting line, we were still stuffing the space under the dodger tight with dry bags full of food, gear, and tools. When the gear was all stowed, the only living space that remained for us, both 6′ tall, was a ludicrously small 4′ x 4′ section of seats. Before backing the boat off the trailer, we thanked and hugged our small group of loyalists. The long road that had brought us to the boat launch had been full of unforeseen circumstances, among them a recent automobile accident that had cracked our centerboard and dislocated Thor’s shoulder. We were just happy to be at the start.

I stepped into the ocean and felt the chilly water squeeze the dry suit tight around my calves. Pebbles shifted grittily under my feet as I eased the boat into the water and pivoted the bow around for launching. The gleaming amber varnish contrasted with the gray and muted blues of early morning, and the 41-year-old boat’s beauty made me think that it belonged in a museum rather than the R2AK.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

I steadied the gunwale, which rested only 6″ above the water, while Thor hopped aboard on the opposite side. The boat careened as I made my own entry, betraying the tenderness of its 4-1/2′ beam. Thor tucked himself into the aft rowing station and rowed us away from shore while I set to work raising the mainsail, securing the halyard to the oak cleat at the bottom of the mast. Thor took the helm and pointed the bow into the wind as I raised the jib. The wind caught our sails and as the boat gained way, I crouched beneath the boom and struggled to organize the mess of lines. A cry of “Go Team Funky Dory!” rang out from the pier, and I was shocked to see just how many people were watching us. The slosh of water at my feet snapped my attention immediately back to the boat.

LOOK FAR had been out of the water for weeks while we sanded, varnished, drilled, glued, and puzzled over how to turn a 16’ Swampscott dory built in 1978 into an expedition race boat. Nine months earlier, Thor had found her under a tangle of blackberry bushes by the Columbia River, rotting away from neglect and exposure. Her path to recovery and improvement had continued until the very night before the race as we spliced shrouds by headlamp. Now, as water trickled in through imperceptible and unrepaired cracks in the planks, 1,000 hours of work were being eclipsed by our failure to get the boat in the water early enough to swell up.

Within minutes, the water inside was above the floorboards. On top of the steady trickles coming from below the waterline, every time the boat heeled, water seeped in at the sides through cracks that had formed around the lap rivets. For bailing, we had a gallon milk jug and a small electric bilge pump. Unfortunately, we hadn’t had time to wire the pump and it was in a dry bag stuffed in the bow; the milk jug was our only option. Balancing our weight in tandem, Thor and I alternately leaned in and out of the boat to allow me to reach the bilgewater without swamping us. I hurled jugful after jugful over the side.

We immediately fell even farther behind the fleet. The larger boats quickly disappeared around Point Wilson, soon followed by the smaller craft. A short time after we passed the Point Wilson lighthouse, the lone stand-up paddleboarder passed us by taking advantage of an eddy along the shore. As he went by he shouted out an overly optimistic “See you in Alaska!” Steaming in frustration over our poor speed under sail, we changed course and landed on a boulder-strewn beach near McCurdy Point, just 5 miles from the start. As Thor lifted the rudder off the transom, I hopped out into waist-deep water, grabbed the painter, and threaded the boat between the submerged boulders to a patch of sand. Thor dropped the sails and I set up the rowing stations for tandem rowing. With the boom detached, we lifted the mast out of the center thwart, wrapped it and the boom in the sail, then tucked one end of the bundle under the aft thwart. The rolled-up spars stuck out haphazardly beyond the stern. A quick handful of beef jerky and we launched back into the gentle surf.

One of the greatest advantages of our 16′ boat was the possibility to pull her up on land. Whether that was for boat work, avoiding a questionable anchorage, or just to stretch and feel solid ground, I grew to greatly appreciate the dory’s versatility. It almost made up for its slow hull speed and inability to keep above some wave crests. Almost.

We were not able to row for long. I had dislocated my elbow ten weeks before the race, and Thor had dislocated his shoulder just six weeks before. The wind picked up swiftly and my elbow burned with the effort of pulling the oars to plow LOOK FAR through the chop. Exhausted and in pain, we once again retreated to land, this time through crashing surf to a pebble beach not a quarter mile beyond the previous stop. We hopped into neck-high water and manhandled the dory up onto the beach. We raised the sail rig again and launched back into the waves. After hauling the boat out past the break line, we counterbalanced each other and crawled aboard simultaneously.

I raised the main as Thor went to drop the centerboard; it refused to move. We pushed our fingers and various objects into the hole atop the case to push the board down, but it would not budge. In our haste to pull the boat above the surf, it seemed pebbles had lodged inside the case, firmly jamming the board in place. Defeated, we returned to the pebble beach. It seemed that our months of working on LOOK FAR had produced a boat scarcely capable of a 7-mile journey. We pulled her up as high as we could on the narrow beach, our optimism in the boat seeping out of it as quickly as the water had leaked in.

We took stock of our situation and decided we could not continue in our present state. It was already late afternoon and we had serious problems. We had intended to make it to Dungeness Spit, 10 miles to the west, but this was clearly out of the question. Just 2 miles away, the siren of Protection Island glimmered in the white gold of a bright afternoon sun. While the rest of the race fleet was likely within striking distance of Victoria, we were stuck looking at Protection Island. If we were going to attempt a crossing of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, we would have to wait until tomorrow.

Unable to sail, we set to work repairing things. Thor and I pulled everything out of the boat, removed the top of the centerboard case, and rolled the boat on its side. We used long pieces of driftwood and bits of line to pry the pebbles out of the case one by one. We reassembled the centerboard case, pushed seam compound into the larger cracks to slow the leaking, and set the boat high on the beach for the night. Tasks finished, we rewarded ourselves with a hearty mac-n-cheese dinner and lingered in the beauty of a tangerine sunset. The stars were soon above us and we huddled between driftwood logs in our bivy bags. Gale-force winds howled around us on the exposed beach and surf crashed just a few yards away.

Our first day in, things didn’t exactly go to plan. Someone once told me: “When everything goes wrong, all you really can control is your attitude and how you handle it.” So here we are taking a selfie and making the most out of our leaking failure of a first day. A selfie for the moms, thumbs down for the boat.

We were up at 4 a.m. the following morning. Thor set to work with pliers, a beach pebble, and a butane lighter to wire the bilge pump into the battery box. I prepared coffee and oatmeal for a quick breakfast, and we launched at first light.

Conditions were ideal to start, and our little boat surged quickly out into the Strait of Juan de Fuca for the 25-nautical-mile crossing to Victoria. Our work on the leaking cracks had greatly diminished the flow of water into the boat, and we watched as Protection Island shrank rapidly behind us. We sailed northwest for Vancouver Island as a westerly wind ripped across a powerful spring tide approaching maximum ebb. An hour offshore, lines of whitecapped tidal races pulsed with the pull of the ebb. Spray blew over the dory’s dodger and into our faces. I clipped the race-tracker beacon to my life jacket and Thor clipped an EPIRB to his, our sober acknowledgement of the gravity of the conditions.

Cresting waves were coming at us from several directions, each one capable of swamping us if hit at the wrong angle. The electric bilge pump was working, but it couldn’t keep pace with the water sloshing over the gunwales. I began to bail and kept at it non-stop, easily filling the milk jug with each plunge into the bilge. We treated each wave as a unique obstacle, shifting our weight and easing and tightening sheets. We ran this gauntlet for hours, so singularly concentrated on survival that we were in disbelief when the buildings of Victoria came into view. Slack tide provided us the brief opportunity to drink some water, eat a protein bar, and pee, activities which were not possible during the six-hour crossing.

A mere 1/4 mile from Victoria Harbor, conditions deteriorated in the span of just a few minutes. Winds gusted to 30 knots, and Thor and I hiked out as far as we were able to, cursing our failure to reef. We passed the first channel marker and found ourselves in the path of an outbound ferry, COHO. We tried to tack out of the way, but the jibsheet snagged on a cleat on the mast mid-tack, pitching us sideways. One wave was all it took –water rushed over the side and in seconds we were under. Still sitting in the boat but in chest-high water, my hands shaking, I grabbed the few loose items that were about to float away. Thor shouted at me to hold on to the sheets.

Astonishingly, as the sinking dory stabilized with the gunwales several inches below the waterline, our mast, boom, and sails remained proud above the water and continued to propel us forward. I looked to Thor in bewilderment as we held on for dear life, the heavy air pulling us out of the path of the COHO and across the harbor entrance into the cruise-ship terminal.

Once inside the sheltered waters of the terminal, we dropped the sails and I hopped into the water, swimming and hauling the boat by the painter over to the 6’-diameter rubber bumpers along the wall. Climbing out onto an algae-coated bumper, I used an oar and my foot to stave off the dory from smacking into the bumper as Thor used our 5-gallon two-handled emergency bathroom bucket to bail. With my weight out of the boat, Thor made good progress. Unfortunately, the bumper was not a friendly place for the dory in the yet choppy waters, and we elected to try anchoring in the terminal instead. Beneath an ironic “Welcome to Victoria” sign, our anchor held and we were able to finish self-rescuing. It took us a good 30 minutes to restore our boat to our standard several gallons of water in the bilge.

With adrenaline wearing off, we stowed the sails, set up the aft rowing station, and proceeded the final nautical mile through the harbor. Our survival was now guaranteed, and the realization sank in that we might actually make the 5 p.m. cutoff; the dock bearing the bell marking the end of Stage 1 of the R2AK came into view with 15 minutes of the allowed time left. Pulling into the dock, we were welcomed with two cans of warm beer and hearty congratulations. Hungry, exhausted, and relieved, Thor and I walked over to the bell, and cracked the beers. Although the skipper conventionally takes the honors, Thor did not stick to tradition. We cheered and rang the bell together to mark our arrival.

The city of Victoria was kind to us. Our fear that our battery and electrical system had been ruined during the swamping proved unfounded and the Canadian Coast Guard returned our dry bag of safety gear which had been found floating in the harbor. During our rest day, friends from Team Sail Like a Girl helped us get supplies to modify our snotter and reefing system and install a boom vang. With our gear and projects strewn across the dock, racers, race fans, journalists, and the general public stopped by to pepper us with questions and show support. Most seemed as surprised as we were that we had made it across in time.

Our work took us late into the evening and ultimately just the two of us remained on the docks. Katherine, a journalist covering the race, generously offered us the use of the pullout couch in her hotel room. Happy to have one final night of comfortable sleep, we walked the deserted streets of Victoria to her hotel at 1 a.m., our way illuminated by thousands of city lights. Once in bed at the hotel, I savored the crisp sheets and soft pillow, trying to burn the sensation into my memory to recall in the days to come.

At noon the next day, Thor and I stood sweating in our dry suits as the bell went off signaling the Le Mans start of the roughly 700-mile-long second leg of the race to Alaska. We were going to be slower on the water than almost all of the other teams, and there was no sense in fighting it, so we walked rather than ran to our boat. As underdogs, racing for a participation award seemed as much as LOOK FAR and our injured bodies could expect. Once outside of the harbor, the rough waters to the south that we had battled over the two previous days were now flat as a pancake all the way back to the Olympic Peninsula, where the sun was reflecting off the snowy peaks.

Pictured here is LOOK FAR’s version of motorsailing and our sail displaying the many lovely people and businesses who supported us and made the journey possible. We received incredible community support and would not have been able to even get on the water without the help of others. The R2AK pulls together an extraordinary community of individuals who are passionate about the environment and the spirit of adventure.

We commenced “motorsailing.” Thor held the boom away from my head while I rowed. I did a one-hour stint and then we switched. We only made 2 or 3 knots with this technique, but dropping the sailing rig seemed risky given the cumulus clouds to the south. Two hours later, we were sailing downwind at 5 knots along the Strait of Georgia under clouded skies. I happily watched the last islands of familiar land fall away behind us.

That night, we tucked into a small bay off Prevost Island, a more than hospitable place to spend our first night sleeping aboard. We stacked dry bags on the floorboards, followed by sleeping pads and bivy bags stuffed with mummy bags—there was just enough room for two. Exhaustion and the calm waters lapping lightly against the hull pushed out any misgivings I’d had about sleeping in a boat with only 6” of freeboard.

Pushed gently along by a southerly up the south side of Galiano Island, we passed beneath the bows of tankers on anchor in Nanaimo (at right on the horizon). While in their presence we debated the trade-offs of globalization and the conflict of industry and nature. Confronted by the beauty of the Inside Passage, it’s difficult to feel moved to take the side of industry, and we were eager to put distance between us and the larger vessels.

As we rowed north toward Nanaimo, industry pressed in along the shore where I had expected we’d find wilderness. Towering above our dory, oil tankers at anchor were steel giants intruding on the soft-edged beauty of the Gulf Islands. Log booms lined the shoreline for miles and houses occupied the remaining waterfront.

Squeezing in among the fishing boats of Port Nanaimo, we left LOOK FAR to restock on provisions. Stripping off our dry suits was liberating, and in the hot sun we indulged in a pint of Häagen Dazs each before resuming our slog north. It’s the small rewards that keep you focused in an endurance race, and few things are more motivating to Thor and me than a pint of ice cream.

Our search for wilderness continued. When we pushed through the seething boils of a dying flood tide in Seymour Narrows and settled into the glacial views from Plumper Bay, it seemed we had finally found it. Eagles swooped down to catch fish in the dying twilight, and we began arranging the boat for an evening on anchor. Out in Discovery Passage, seven cruise ships invaded our quiet wilderness with blasts of their horns and large clouds of smoke, parading through the narrow tidal gate at Seymour, one right after the other. Left in a cloud of diesel exhaust, the dying light refracted gold through the remaining haze and I couldn’t help but feel ashamed by what civilization has done to these waters.

Sleeping in the dory at anchor was surprisingly comfortable, but most certainly an exercise in trust. I could drop a hand over the edge and touch the water without putting my wrist below the gunwales. Combine that with wave action and being zipped into a mummy bag that’s stuffed inside a bivy sack, and stress dreams inevitably disturbed my slumber. Thor, on the other hand, appeared unfazed and snored his way through most nights on anchor.

In Discovery Passage, the morning flood tide ripped through the mile-wide channel, forcing us to row into the back eddies with our oar blades a mere 1’ away from the barnacle-encrusted granite cliffs. We craned our heads over our shoulders, keeping watch for lurking boulders in the dark water. Sea lions and a solitary minke whale passed us on our way, and the sun kept us warm and smiling despite slow progress north up the passage to Johnstone Strait.

As we rounded the corner into the strait and began to head west, the afternoon turn of the tide arrived with a series of strong gusts of wind. Thor was taking a light snooze and I shook him awake to the rapid change in conditions.

“Dry suits on,” I said. “Something is about to go down out here.”

Within five minutes, what had been a glassy-smooth sea was seething in whitecaps. With no time to reef and the wind too strong to pause, we were vulnerable. We rode a single tack north across Johnstone to the only sheltered beach in sight. By the time we reached the lee of the headland protecting the beach, the water inside the boat was just two planks below the gunwale.

We landed and while I emptied out water and lashed our supplies in, Thor put a double reef in the main. We were determined to make miles and headed back out. Rounding back into Johnstone, the full force of the wind heeled us over immediately and we resumed bailing steadily. The current had strengthened, forming messy patches of standing waves and large whirlpools. Driftwood logs spun in place as the wakes of freighters headed south ricocheted off each other.

Johnstone Strait is full of tiny, secluded, charming coves. In many spots, the sandy bottoms and good sunlight can almost fool you into thinking you’re in the Caribbean. Until you stick your hand in the water. Ocean temperature aside, these bays made excellent spots for a quick snack and a moment to appreciate our progress through the ever-changing landscape. We were moving just slow enough to observe the subtle changes in geology, wildlife, and climate as we headed north.

Occupied more by bailing than by sailing, we decided to make for the only sign of safety, an unnervingly short little fingernail of a beach. With no other option, we were forced to gamble that the high tide wouldn’t flood the beach we’d have to land on. We unloaded all of our gear and pulled the boat up as high as possible, the bow nosed into the forest and tied off. We pitched our bivies on the forest floor. There were piles of bear scat not 20′ away. Spooned around our only can of bear mace, I slept fitfully.

After an adrenaline- pumping day in Queen Charlotte Strait and a wavy approach to the beach, we emptied LOOK FAR and pulled her high up onto the logs to spend the night. We were lucky to find a plentiful supply of dry wood and used my hammocking tarp to keep us dry and warm through most of the rainy night. In the dark, with rain pelting down on the tarp above, I wondered how many souls had spent a night on this unnamed beach in a cove with an entrance just wide enough for a boat our size.

When I awoke to the shadowy light of dawn, the trees were heaving in the wind, and Johnstone Strait remained too dangerous to sail or row. I was secretly happy for a guilt-free excuse to make some much-needed repairs during the day and enjoy a full night’s rest.

We left the beach at sunrise on the second day and made our way up the Strait with the sea state still on the edge of precarious. Around 10 in the morning, the winds again peaked and forced us to pull off at Sayward, a once vibrant logging town that’s now a sleepy settlement with only a few hundred residents.

At first glance, it appeared to be a ghost town. There were trucks and RVs parked next to the community pier, but not a soul was to be seen. The wind howling, it seemed eerily deserted. It felt good to stretch my legs and we headed toward the pier where we found a small gift shop which wouldn’t open until 11 a.m. Next door was a place marked “Al’s Room.” It was evidently designed for people like us, wayward souls with no shelter in need of a warm, quiet space. Its doors never locked and anyone was welcome to enjoy its microwave oven and selection of steamy romance novels. What luxury!

At 11, a bubbly woman stuck her head in the door. Sue, the gift-shop manager and mayor’s wife, informed us we were welcome to stay in Al’s Room for as long as we needed. After spending the day watching the water and hoping for a break in wind—which never came—she convinced us to join her family for dinner at her house. Sitting around the table, the luxury of a cold beer and a home-cooked meal made it easy to forget how slow a race we were running.

Johnstone Strait was a particularly trying part of our journey. For days on end, as the tidal currents of up to 5 knots switched directions in the late morning, opposing northwest winds gusting up to 35 would kick up and make forward progress in the dory impossible. We spent many hours on land watching the whitecaps froth and listening to the winds howl through the trees around us, as clouds blew over the snowcapped peaks in the distance. Forced to remain ashore while other larger craft such as this seiner headed north weathered the storm, we were grateful for the enthralling views.

At first light we left Sayward and resumed our slog up the Strait. It took several more days of dancing on and off the water to make it out of the erratic conditions of Johnstone. By this point, we began to see R2AK boats that had already finished the race and were heading back home from Ketchikan. It became apparent that we would be knocked out of the race by the Grim Sweeper, a delightfully named sweep boat and “rolling disqualifier” for those who don’t reach Ketchikan before it.

After a 16-hour day of rowing, we stretched out our aching bodies on the docks of Port McNeil and evaluated our position. We were not yet halfway to Ketchikan and about to enter unbroken wilderness, but our bodies were failing. The ache in my elbow had transformed into ominous pangs of acute pain that would radiate up my arm while I was rowing. Thor was struggling with his shoulder and needed to take longer breaks from rowing more frequently.

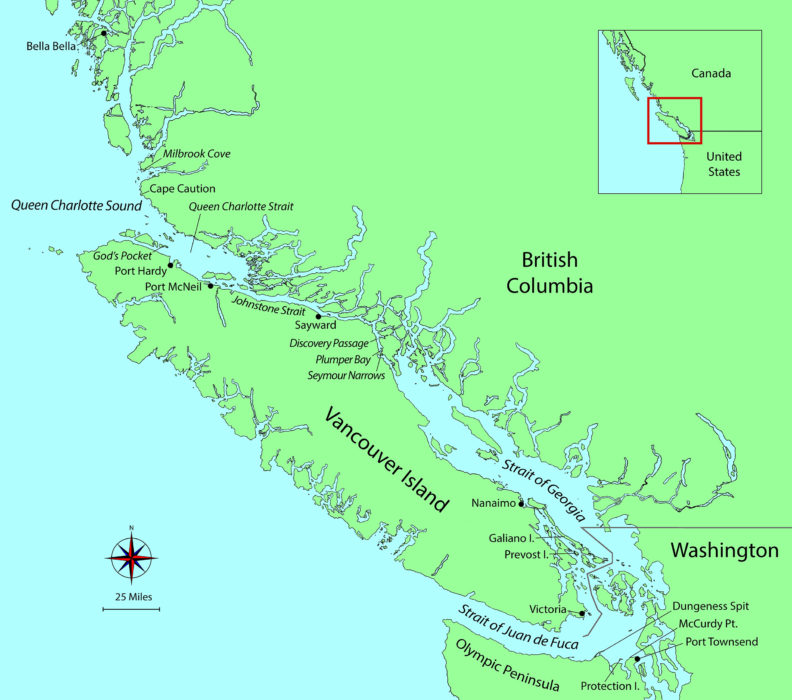

There wasn’t much choice in the matter—we had to withdraw from the race. We sent word out for Thor’s girlfriend to meet us with a trailer in Bella Bella. Bella Bella wasn’t quite Alaska but it was the section of British Columbia coastline that we were most excited to see. We had come too far and worked too hard to call it quits on Vancouver Island at Port Hardy. This left us with two challenges remaining: navigating Queen Charlotte Strait and rounding Cape Caution.

Queen Charlotte Strait is a dangerous area. The swell of the Pacific Ocean rolls in to meet the powerful tidal surges of Johnstone Strait and the outflow of several glacier-fed rivers. The confluence of the waters and the wind can be tame at times or lethal. The advice from the locals was to hug Vancouver Island until we can safely cross to God’s Pocket, an aptly named island chain of exceptional beauty. We’d spend the night there and wake up before first light; if there is any wind, we don’t go. If it’s clear, we row like hell. Conditions are known to deteriorate rapidly over the course of a day, making rounding Cape Caution risky. Even large boats take the Cape seriously.

Sailing in flat water is a rare treat along the Inside Passage and was truly a wonderful experience in LOOK FAR. No water came in over the sides, and Thor and I weren’t forced to bump into each other as we tried to balance the boat. Our momentum wasn’t swallowed by every wave trough, and the laps of the planks happily displaced the small wavelets in its path. These conditions made Thor and me smile from ear to ear whenever we came across them.

We entered the sheltered area of the Sound by midafternoon, happily sailing past Port Hardy, and aiming for God’s Pocket. God, it turned out, had other plans for us than the safety of his pocket. Dark clouds appeared to the west, menacing us with a sound that most resembled a freight train approaching.

“Is that the wind?” Thor asked in disbelief.

“I think we need to turn around,” I responded.

We did, and less than a minute later the choice was validated as the right one while we hurtled back toward Port Hardy, taking on water at an unsustainable rate. We wouldn’t make the town so we instead tucked into the bay at its edge, a small cove host to an off-grid fishing lodge.

Prior to the R2AK, I had never really seen a log boom up close and personal. Rowing up next to one, Thor was eager to climb out and take a picture. A tanker wake passed by not a moment after this photo, forcing Thor to make a leap back into the boat as I quickly rowed us out from the impact zone with the logs. There were many moments of near calamity on our journey, and this was an early reminder to always keep our wits about us.

As we tacked back and forth along the entrance to the cove, a man in the interior dragged logs erratically by motorboat to create a barrier. No communication was made despite our obvious distress.

After ten minutes, the man finally shouted out “Y’all screwed up or what?”

The humor was not lost on us. We yelled back, “We’ve been better!”

“Well, you better come land. I’m Dave and this is my lodge.”

He escorted us in between the logs and instructed us to land on his dock. It hadn’t taken him long to evaluate our situation. To the motoring fisherman, our journey was reckless and bordered on absurd. He gave us each an apple, a cup of coffee, and a floor to sleep on inside a small unfinished cabin that had a roof but no windows. Dave entertained us with tales of humpbacks burping up seagulls and orcas cornering pods of dolphin in his bay. He was unpolished and proud, generous, and strangely charming. His stories were hilarious and the following morning, as we departed for Cape Caution, he sent us off with some frozen salmon for the rough day ahead.

We sailed north through two glimmering island chains and at the opening of Queen Charlotte Strait we encountered the Pacific swell. It gently lifted and dropped us several yards, bringing Cape Caution in and out of view. By the time we reached the exposed headland, intensifying afternoon squalls were chunking up the water. There are very few hospitable beaches near the Cape, and the swell makes a surf landing and launching dangerous. We were forced to sail 2 nautical miles back away from the cape before finding a bay with enough protection from the swell to attempt a beach landing. When we came ashore we spotted fresh wolf and bear paw prints below the high-tide line; the patter of rain spurred us to action. Under a tarp supported by driftwood, we set our bivies on the wet sand and built a large fire. We kept it alive until morning to deter the predators from coming too close.

The rough conditions persisted the next morning, but we elected to go anyway. Explosive waves around the Cape made it safer for us to sail miles out to sea, coming about only when we were positive the port tack would clear the point. Our two-man balancing and bailing act kept us afloat as we endured the open ocean slapping us around. North of the cape, spray blew up around us from a series of hidden rocks and ledges. Not daring to stop even to eat, we pushed on until sunset. The golden rays of another day gone by ushered us into the protective cedar-draped shores of Milbrook Cove, 10 miles north of the Cape. We were happy to have the company of throngs of bald eagles and a sea otter happily hunting in the kelp beds.

It took us three more days of continuous rowing to reach the village of Bella Bella. The tidal exchanges were large and each low tide exposed a rich world of color. Magenta and ochre sea stars and crimson sea urchins dotted the yellow rocks, vying for space in the intertidal zone. Despite the bone spur I could feel growing on my elbow, my brain began playing tricks on me, challenging my decision to stop and encouraging me to ignore the pain. Who needs a left arm after all?

When we were within sight of Bella Bella, everything inside of me was fighting our logical, safe choice to withdraw from the race. But for better or worse, it had already been decided, as the wheels were literally in motion to bring us home. Our loved ones with a truck and trailer were headed up Vancouver Island at that very moment. We approached the public dock and tied up among the fishing vessels.

Without needing to do any work on the boat and our contact in Bella Bella busy until the evening, we took our free moment and sought out a consolation prize of cold beer. Thirty minutes and two tallboys later, Thor and I were seated on a concrete slab adorned in graffiti, gazing out on the harbor.

Thor and I had sought out the Race to Alaska as a venue to share our passion for the ocean and boats with kindred spirits and raise money for Pacific Wild, a nonprofit dedicated to pushing for wildlife protection and environmental rights in British Columbia. For me, visiting their headquarters in Bella Bella was a personal victory despite the failure to finish the race. The race structure had brought my ego into the forefront: pushing myself both physically and mentally. Failure freed me from that and returned my focus to the ocean, to its many lessons and gifts, to peace and gratitude for my experience. Our journey to Alaska, for now, was finished. ![]()

Pax Templeton was born in 1992 and grew up exploring the woods and beaches of Maine and the desert of New Mexico. For the last several years, he has lived seasonally between Utah winters and Washington summers, kayak guiding, skiing, and commercial fishing. Always up for an adventure, Pax has a deep love and appreciation for the ocean and the ability to go by boat where no roads lead. He became exposed to the world of sailboats through his friendship with Thor and learned most of what he knows regarding their operation, upkeep, and repair from him. The R2AK was a steep learning curve and bestowed tremendous respect for the Port Townsend and R2AK community, wooden boat builders, the sheer power and beauty of the ocean, and the capabilities of a 16′ Swampscott dory.

Thor Belle had a boat well before a car and grew up poking around tidepools in Maine and spending as much time as possible in, on, and around the Atlantic Ocean. Thor is happiest when it’s cold out. He has adventured all over the world and has many years of experience on the open ocean delivering sailboats in the North Atlantic, teaching environmental education and big-boat sailing, and working for commercial sail charter businesses. He firmly believes in boats as a way to connect people to their environment and hopes to devote his life to doing just that.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Great story, guys! Thanks for sharing it.

I really enjoyed reading this! Thank you for sharing. Aside from the leaking hull troubles, I am curious about the author’s or anyone else’s perspective on using the Hammond 16* for this kind of expedition.

*The Hammond 16 is a Swampscott dory presented in John Gardner’s The Dory Book with a page of drawings and offsets. Ed.

Thanks for sharing this story in such detail. We read it, enthralled, remembering all the details of our own journey through those beautiful, wild waters. You guys were so darn tough. Hope you keep adventuring, maybe in a slightly bigger boat. 🙂

-Team Backwards AF

I haven’t laughed so heartily, in that unique way of both appreciation and commiseration, in a long time.

Congratulations on both the journey and the retelling.

Thanks much!

The Inside Passage: it doesn’t matter where you end up. You go, you win.

Hi Guys,

Funny story. I really enjoyed it. With name like Thor and Pax, it dawn on me, you are the two bought Watermelon. I hope it does a better job of keeping the water out.

Cheers,

Uly

Loved the story and adventure! Thanks for sharing this well-written expedition!

Awesome well-written adventure. Challenging times can forge great friendships. Hoping next adventures are soon.

Well done and well written. My own adventures on the water have been more modest than this, but cold water and high winds, available even within an hour’s drive of metro Atlanta, have sharpened my own sense of mortality and humility. Thanks for sharing your story!

Your story puts me in mind of Susan Conrad’s book “Inside,” in which she describes her ordeal paddling a kayak from Anacortes to Juneau in 2010. This was a solo journey. She lives (still, I believe) in the tiny town of Oso, WA, some miles up the Skagit River.

I have paddled (with various paddling friends) on two trips in the Bella Bella area. The first time, after being deposited by the ferry at Franklin Bay, 2 or 3 miles south of Bella Bella, we started the hike into town for dinner. As we trudged along we paid little attention as a car passed us heading our direction. Ten minutes later, it came back, did a U-turn in the road, and the driver offered us a ride. He explained that the first time he saw us, his car was too loaded with stuff to accommodate us, so he unloaded his gear at home and returned to pick us up. We were very appreciative of this generous act of kindness.

During our first ride up on the ferry, a young woman was admonishing anyone planning to paddle in the area to check in with the first nations band. Which we did. Later, as we explored around the area, we had the feeling that small boats passing in the distance were checking on our welfare; as I have also become aware during Baja kayak trips, locals are often generous and kind.