The line of Kaholo stand-up paddleboards (SUPs) from Chesapeake Light Craft merge a trendy new sport with the world of build-it-yourself wooden boats. These kits are thoughtfully developed, and they yield a state-of-the-art wooden SUP. For those wishing to scratch-build, plans consisting of instructions and full-sized patterns are available as well.

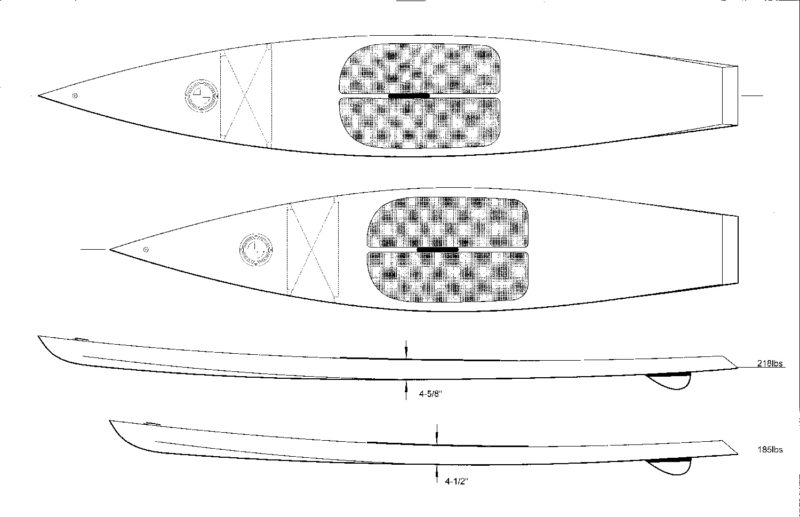

In just a few years, the CLC boards have already evolved through several generations, refining their dimensions, strength, and ease of construction. The hulls are beamy and stable, with a flat run aft, reverse transoms, and a very pronounced V forward. The boards have an actual boaty-looking, wave-cutting bow. Two models are offered, at 12′ 6″ and 14′, to accommodate smaller and larger paddlers, respectively. The newer 12′ 6″ model was also developed to conform to class-racing rules.

As we all know, two boats in sight of each other automatically means a race, and SUPs are no exception. Classes and events have developed, as have different SUP tribes. The various denominations include surfing, open-water races, flat-water racing, whitewater paddling, and touring. There’s great potential for paddle-board expeditions, too: Two evidently unemployed 20-somethings paddled the East Coast from Key West to Portland, Maine, last year. Less ambitiously, I have added picnics and evening cocktail cruises to the list of SUP pursuits, deftly strapping a cooler to the aft deck.

Yes, stand-up paddleboards have spread across the water sports world like the flu in a college dorm. I can judge by the fact that there are now paddleboard yoga classes in Burlington, Vermont, that the boards and their believers are ubiquitous. I’m in my second season of joyfully paddling my board, so I understand their popularity, but I admit that once I agreed to write this review I had to do a little web surfing to figure out their origins.

I first noticed SUPs a few years ago, when the big-wave surfer Laird Hamilton was having his 15 minutes of fame and appearing as an American Express “It” boy. Stand-up paddling was striking, looked cool, and was easy to imagine as a “no waves day” kind of cross-training way to get out on the water. Turns out that that is just about the complete story. Ancient SUP history cites beach-boy surf instructors in 1960s Hawaii resorting to canoe paddles and the era’s long surfboards to take pictures of the tourists taking surfing lessons; standing up to paddle kept their cameras out of the water.

Jeff Meyers

Jeff MeyersChesapeake Light Craft estimates the build time of a Kaholo to be 60 hours. Numerous options are available for customization; the deck pattern seen here was accomplished by embedding Hawaiian shirt fabric under epoxy.

The contemporary SUP was developed in Hawaii a little over a decade ago, and has only recently spread to New England—and circled the globe in the other direction just as quickly. The jump to the East Coast from the West may well have been expedited by, if not at least coincided with, the teaming-up of California SUP guru Larry Froley with the boffins at Chesapeake Light Craft for the design of the Kaholos.

The appeal of the sport is rich and complex. First and foremost is simplicity: It’s just you, a board, and a paddle. Second is the easy learning curve. Turns out the instinct not to fall in the water is pretty primal. One of my kids and I recently spent a day watching beginners try out SUPs, and came to the conclusion that if you are the least bit active and have ever done anything requiring balance, like riding a bike, skiing, or even climbing stairs without clutching the handrails, you’ll be fine. I’ve been paddling frequently for two seasons and have yet to fall in. A third appeal is that paddling a SUP can be as physically demanding as you want, again much like cycling. One can indulge in a leisurely drift around the pond, or jump on for an all-out aerobic workout. You can pick locations and conditions to suit your mood and skills. The muscles involved relate most closely to Nordic skiing, in my experience. After a long paddle my calves and the balls of my feet are the first constituencies to report, then the next day I hear from my shoulders.

The fourth reason for the SUP craze is a board’s transportability. They are just about the easiest cartop load imaginable, and their minimal accessories leave the rest of the vehicle free for whatever your real reason for traveling. Thus it is easy to keep the board handy for spontaneous outings, or to plan a paddle at the end of the day on the way home. Mine lives on top of my truck for the summer. Finally, let’s acknowledge the surreal, giggling fun of standing up as you essentially walk on water. It is hard to describe, but is a very commonly expressed feeling among SUPaddlers. The water, the scenery, the bottom of the ocean, even wildlife are all crazy different and better from a stand-up perspective.

The structure of the boards will seem familiar to anyone who has seen or built a plywood kit kayak. The hull and deck are 3mm okoume plywood, stitched around a complex but ultralight grid of transverse web frames and longitudinal stringers. The underside of the deck is sheathed with fiberglass cloth before assembly, then the completed hull and deck exterior are sheathed in 4-oz ’glass as well. Epoxy is used both as the construction adhesive and for sheathing. Dual skegs are required for reasonable tracking, and they are provided with the kits, already shaped and epoxy armored. An interesting quirk of the Kaholo’s light construction is the necessary fitting of a vent or breathing tube in the finished boat, allowing the completely sealed hull to equalize air pressure when the air inside it expands. Along with the vent fittings, carrying handles and nonskid deck pads are included in the kits. Indeed, a Kaholo kit comes complete with all materials needed, less paint, varnish, and paddle. The most important thing in the kit is the excellent instruction manual, which leads you step by step with clear, concise explanations and key photos demonstrating the techniques and standards.

The completed boards are light (officially 29 lbs and 32 lbs) and very stiff. They are structurally strong and durable, but they must be treated as wooden boats—which is to say, with some care. Losing one in the surf on a rocky shore won’t end well, nor will parking-lot falls or unruly jumping about. Skegs stick out, and as they teach you at boot camp, things that stick out get broken. The best practices for long Kaholo life are to remember to strap them down and to mount and dismount in a foot of water. In my learning to paddle and adventures to date, the only indignities my Kaholo has suffered are a few paint chips and scratches.

While on the topic of best practices, let me offer a few of “novice beware” warnings: Paddling into a wind of any strength while standing is next to impossible. Kneel or even lie down as necessary. Second, keep in mind that cold water is dangerous and dress appropriately. Paddle where you can walk home until you are confident. Make adult decisions about PFDs (the Coast Guard considers you a vessel), and contemplate an ankle leash, as your board may well drift faster than you can swim.

Jeff Meyers

Jeff MeyersAuthor-builder Geoff Kerr explores the thin waters on the edges of Vermont’s Lake Champlain on a 14’ Kaholo stand-up paddleboard. The board is available as a kit from Chesapeake Light Craft in Annapolis, Maryland, and plans are available for scratch-builders.

Prices for the kits make the Kaholos competitive with manufactured boards as long as you only pay yourself $1.89 per hour to build it. The performance of the finished product makes them a bargain, as of course does the personal satisfaction of building it. Perhaps the most fun is the joy of customizing the finish of your SUP. The newly popular practice of applying decorative fabric under the deck glass makes every home builder an airbrush artist without the health and social risks of smoking all that inspiration. The project s officially thought to take about 60 hours. The company’s estimates are a good-faith effort to represent the time required, and are especially valuable relative to their other boat kits. While I agree with this estimate, suffice it to say that results may vary. Nevertheless, the Kaholos are the easiest kit in the CLC quiver, and very simple to build. For some context, students can complete Kaholo kits in a one-week class with no strain or panic, driving home on Saturday with a board that is ready to sand and paint. Tool requirements are minimal, limited to a few simple hand tools plus some spring clamps, a drill, a block plane, and a sander. Shop requirements are also easy. Some floor space (maybe 5′ × 18′ ) and a pair of sawhorses will do nicely. I banged my first Kaholo together in a corner of my shop over the Christmas holidays one year, a few hours a day here and there between family visits. A project like this lends itself well to a routine of an hour or two after work each day ’til you are done.

A Kaholo is a great introductory boatbuilding experience, the sport is a “good for you” hoot, and it may well be the one boat on your beach that everyone in your family can use. That’s a hard-to beat-proposition. Try not to giggle too loudly. ![]()

A series detailing the construction of the Kaholo begins in the November/December 2012 issue of WoodenBoat magazine (No. 229). Order Kaholo plans and kits from Chesapeake Light Craft.

CLC offers two models of Kaholo: a 12’6” board and a 14-footer. The smaller board is intended for smaller padders; the larger one for larger paddlers or for those wishing to carry a companion or a cooler. The smaller board qualifies for several racing classes, while the 14-footer is meant for touring. Kaholo 14 Particulars: LOA 14′, Thickness 4 5/8″, Beam 29 1/2″, Waterline beam 27 1/2″, Weight 32 lbs. Kaholo 12-6 Particulars: LOA 12’6″, Thickness 4 1/2″, Beam 29 3/4″, Waterline beam 28″, Weight 29 lbs

Hi Jeff,

At 75, not quite ready to build a SUP

but wanted to let you know we’re still thoroughly enjoying the Annapolis Double

Wherry we built under your guidance at

The Wooden Boat School in ‘18.

Nice work Geoff! Good to see you writing and building!