There were three original Chebacco boats, all designed by Phil Bolger for Brad Story. Story was a friend of Bolger’s and a boatbuilder, now retired, of considerable talent in Essex, Massachusetts. All three boats feel very much alike on the water. I’ll make a point of differentiating between them when appropriate, but otherwise comments are true for all three. In fact, on a day of racing them against each other, and trading back and forth to see if any small differences were the result of the people aboard, it was really easy to lose track of which one I was actually on at any one time. They’re that similar. (A fourth, raised-deck version recently joined the fleet.)

The first was an extension—literally—of Bolger’s 15’ Harbinger catboat that Bolger designed for Story in 1975. It was done more to the New York style rather than Cape Cod so that it would row better and need a smaller sail plan. The lines are slack-bilged, especially below the waterline, with significant flare. It’s a fair, easy, dish-shaped, easily driven shape that developed into the sandbaggers. It offers amazing performance in the usual light air of New England (and New York) summers.

The first Chebacco was Harbinger with a 5′ stern fairing and a small mizzen. She was a cold-molded stock design built to order at Story’s shop. The added length gave Chebacco a significantly higher top speed than her predecessor, even better ghosting ability, and allows for a really big cockpit and a small, but quite comfortable cuddy.

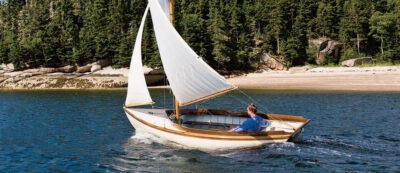

Photo by Jamie Orr

Photo by Jamie OrrThe Bolger-designed Chebacco boat is an 18′ cat yawl based on an earlier Bolger daysailing cat.

Other than the mizzen, the rigs of the first Chebacco and Harbinger were essentially the same unstayed gaff cat with a very short luff, and a long gaff and boom. The shape of the main allows for a short mast, which in the cold-molded Chebacco is a very good thing. It passes through the cabintop and into a step on the sole of the cuddy. It takes some commitment to lift even a mast this short into place and luck or patience or another person to get it into the step. Lengthening the mast for a longer luff, or (even more to the point) to get a vang on the boom, only makes the process harder.

These are corky, light, playful boats on the water. They move effortlessly in light air, heel easily but slowly, accelerate quickly, and become very stable as they settle onto their flared sides. They balance beautifully until well off the wind. In fact, the boats can be steered with the mizzen sheet alone anywhere from a beat to a beam reach. They tack in 95 degrees steering with the mizzen sheet, 90 degrees with the tiller. They become harder-mouthed off the wind, but not offensive. The end plate on the shallow rudder works.

Despite how easily the Chebaccos move, they feel quite deliberate. The tiller is firm, her motions smooth rather than flighty. They feel more like keelboats than light trailer boats. Restful rather than athletic, but not boring, these boats feel much bigger than their 20′ and 1,000-lb displacement would suggest.

Above the waterline they are all volume and open, uncluttered space. The Chebaccos’ cockpits run almost the full width of the boats and about a third of their length. The cockpit size is enhanced by depth and a broad expanse of cockpit sole. The floor space and depth invite getting up and walking around, or sailing with the tiller propped against a hip.

The benches are chair height and width, and are angled down and outboard at just the right pitch. The coamings form high seatbacks. The forward faces of the seats are also angled—wider at the sole—to make for more foot room. The boats are delightful to be aboard.

These kinds of boats have to provide more pleasure than almost any other kind. The list of what makes them so wonderful is long, but let me indulge myself, as they also seem to be surprisingly rare.

They are small, simple, and light enough to launch, rig, and sail alone. They don’t need a slip or mooring, and so save the expense and open up many more areas to sail. They don’t waste a week of spare time fitting out in the spring or putting up in the fall. They don’t demand a whole day if there’s only an hour or two to sail, but they are plenty comfortable for the full day if it’s available. They are sailing within 15 minutes of reaching the ramp.

They’ll take a party to a low-tide beach for a picnic. They sail in the most delightful places: water that’s shallow and close to shore, full of minor dangers and great discovery and sport. They are light and shoal enough to push off a mud bank. They can tow a dinghy, but don’t have to. They can be rowed at a reasonable pace, standing, with long sweeps, or can be sculled over the transom, or can take an outboard.

They sail backwards steadily and predictably, or sideways for that matter, should you want to get into tight places or show off. They spin in their own length under sail. With some tweaking, they’ll steer themselves. These boats are capable enough for semi-open water. They’re fast enough to cover distance. They lie-to like a duck under the mizzen alone should a mistake be made with the weather.

They have a dry place for cold crew members, a shaded place for sunburned or sleepy crew members. They have plenty of storage to keep gear aboard and ready to go, but not underfoot.

Young children will find everything aboard to their scale and will feel much their own people, able to sail the boat and not be bored. Adults, too, will feel everything to their scale. What a difficult combination. Everyone aboard will feel safe.

They are strong, stable, dry, and capable. They’ll take adventurers off for a weekend of camping on the water in far greater luxury than most campers put up with, let alone backpackers. And at the end, it’ll only take a half hour to put the boat back on the trailer and pack it up. And everything is aboard, locked up, and ready for the next opportunity to get out.

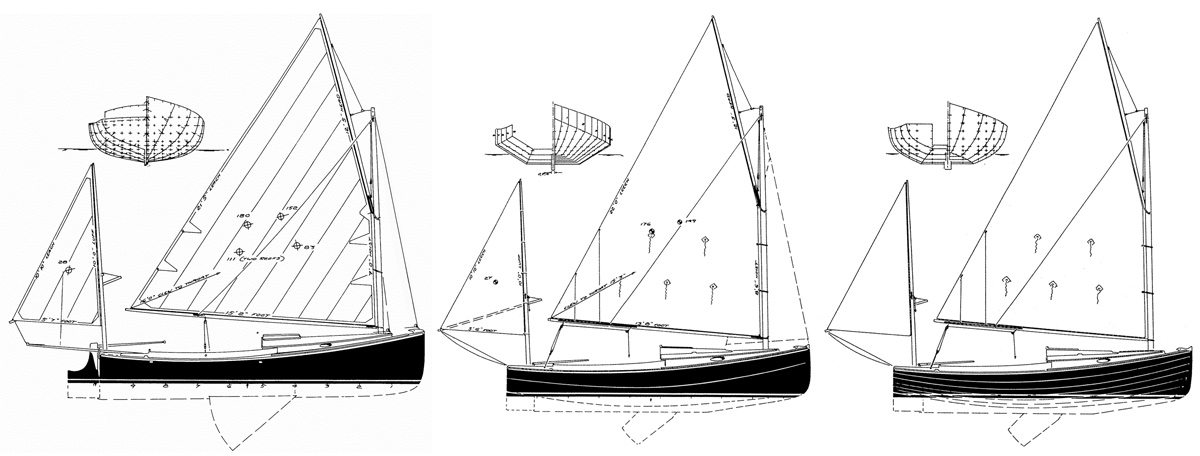

Photo by Onne Van Der Wal

Photo by Onne Van Der WalThe Chebacco concept began life as a cold-molded, round- bilged boat (right). A sheet plywood version (left) followed, and on the heels of this came a lapstrake-plywood version (middle).

Despite all of the virtues listed above, the cold-molded boat got to be too expensive to build. Sales dried up. Story went back to Bolger for a less expensive design in plywood that had all the same properties, plus some added conveniences. It was an opportunity to improve a great boat.

The sheet-plywood boat that resulted retains the plumb ends, the broad transom, large cockpit, and uncluttered cuddy. The rudder was moved inboard to allow a free-flooding outboard motor well on centerline so the motor can be both convenient and out of the way. The huge centerboard of Harbinger was replaced with a much smaller board and a full-length, very shoal keel, though the draft remained at 1′. The keel allows some progress to be made with the board all the way up. It also stiffens and strengthens the flat bottom.

The mast on the plywood boat steps through a slot in the cuddy’s housetop. Place the heel in the step and walk the mast up. Since it’s so easy, the mast is 3’ longer, the boom and gaff shorter. Sail area is about the same, though the rig looks better. And it might be faster.

In almost all ways the plywood boat is more functional, convenient, and usable. Aesthetics are in the eye of the beholder. The sheet-ply boat is all angles. Her upper chines are very much in evidence, her sheer- strake plumb, like her ends. I find her, too, very beautiful, but in a different way than her cold-molded sister: where one is smooth and sensuous curves, the other is cutaways and angled flats. Perhaps an acquired taste, but striking from any angle.

Story liked her well enough, but wondered if he couldn’t do a more traditional-looking boat from lapstrake plywood for the same price and time in labor. There are some people who he thought might not like the look of the sheet version. What extra time he used in fitting the planks, he’d save by not having to ’glass and grind. Bolger drew the third Chebacco.

The lapstrake boat has an apple-cheeked, Brit- ish look to her. Her deck and rig are identical to the sheet-ply boat. The materials cost is the same. Labor time worked out to be about 10 hours more. On board, it’s hard to know the difference between the two plywood versions. The sheet boat might feel a little more tender initially, and harden up more definitely when she gets her upper chine in. But it’s hard to say for sure. We never had more than 12–15 knots of air. At 15 we might think about taking the first reef. At a steady 18 we definitely would. It would be interesting to see if the two boats still felt the same as the breeze came up.

Story did get Bolger to draw one more Chebacco boat. This one was a 25-footer, lengthened to provide better accommodations in the cuddy. It’s plywood lapstrake, and looks very much like the others. I’m not convinced that the added length is not a mistake, though. Too much of a trade-off in convenience, both on and off the water. But that’s the subject of another article.![]()

Designer Phil Bolger passed away in May 2009. His legacy of great designs includes the three-boat, 18′ Chebacco series shown here. A later 25-footer, and a still-later 18′ raised-deck version, followed.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2010 and appears here as archival material. Plans for the 19′ 8″ x 7′ 5″ tack-and-tape version are available from H.H. Payson & Company.

I have always admired the Chebacco, in particular the clinker version. My only problem with the design is that apparently plans are no longer available. Is this indeed so? I’d really like to build one!

https://www.instantboats.com/product/chebacco-19-8-x-7-5/

Try Harold Payson’s site: https://www.instantboats.com/product-category/instant-boats-plans/sailing-designs/

The Chabacco boats are all in the Bolger book, “Boats With an Open Mind.” The offsets and scantlings are there, and if you can build without someone holding your hand, it should be possible to build one right out of the book.

The plywood Chebacco plans are still available from Dynamite Payson’s survivors:

https://www.instantboats.com/product-category/instant-boats-plans/sailing-designs/

Phil Bolger’s widow, Susanne, can supply plans for the other Chebacco varieties. She frequently posts to the online Bolger group:

https://groups.io/g/bolgerboats/

It was a pleasure to see Wayward Lass at the top of the article! :o)

https://flic.kr/p/2mMpv5J

The plans can be obtained from Dynamite Payson’s website for the sheet plywood version.

https://www.instantboats.com/product-category/instant-boats-plans/sailing-designs/

The other designs can theoretically be bought from Susan Altenburger.

The Payson plans are not the clinker (lapstrake) version.

Try Harold Payson’s site

https://www.instantboats.com/product-category/instant-boats-plans/sailing-designs/

Here you go. Click on “References and links”, then scroll down to the bottom where it has a couple of plan sources.

http://www.chebacco.com/

I have the original cold-moulded hull #1. I’ve had it for 10 years and steadily rebuilt most everything on it. I still sail it in the Salem sound where she always gets a lot of positive comments from sailors and non-sailors alike. While I am a graduate of the Rockport apprenticeship ‘88, much of the improvements I made were simply born of common sense. The boat is as much a pleasure to sail as it is to work on. It is a testament to Story and Parlee’s craftsmanship that she is still sailing 37 years later.

I have the original Story-built blue hull in photo and featured in WoodenBoat magazine. I have owned and sailed her for 30 years. I’ve spent the last 7 years working on her, bottom paint, varnish, cockpit, but she has not been launched. Boat-house stored always. Bristol condition. I have 2 other boats (power) and I’m getting too old to manage her.