When John Harris of Chesapeake Light Craft (CLC) came to WoodenBoat School here in Brooklin to lead a six-day class in building his newly designed Tenderly Dinghy and brought two finished boats with him, I jumped at the opportunity to see the progress as he taught, and to take the finished boats for a spin in Great Cove.

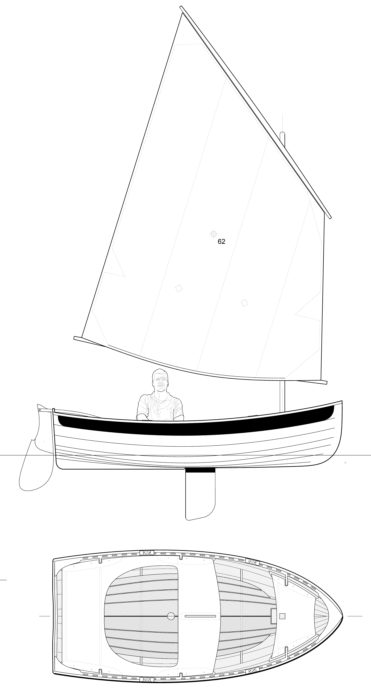

While Harris didn’t draw inspiration from any one particular lapstrake design, the general English clinker day boat aesthetic is apparent. He was looking to do justice to a vision from Swallows and Amazons in a kit boat with attributes that would make for a great dinghy—plenty of volume, good to row, and a worthy daysailer. Harris aimed for a salty-looking design with good stability and carrying capability, and achieved that in a boat 10′ long with a beam of 52″ and a payload limit of 425 lbs. “At a more technical level, what I was pursuing was the most shapely boat I could manage in an amateur-construction context,” said Harris. “Tenderly has a lot of shape for a stitch-and-glue boat. The really full bow in plan view transitions seamlessly into a hollow waterline.”

A few details elevate the Tenderly from a simple kit boat to classic lapstrake heartthrob. The open gunwales, the breasthook and quarter knees, the bead wale, and lovely sheerline belie her mostly plywood construction. When the eight optional floorboards are added, which make for more comfortable seating in the bottom of the boat and drier gear, the very finished appearance is the icing on the cake. What a looker.

Anne Bryant

Anne BryantThe transom and the full bow offer room to stow proper oars. Handholds in the transom ease the tasks of handling the boat on a cart and launching into a chop from a beach. Note the plug closing the daggerboard trunk.

The recommended 8′ oars fit inside the boat when shipped, which is a great advantage. Oftentimes, tenders have to give up 6″ to 12″ of oar length to make the oars short enough to stow in the boat. With a guest or two and some groceries in your Tenderly on the way to your boat at anchor for a sundowner, you’ll be glad to have the proper oar length.

Aaron Porter

Aaron PorterFloorboards come in handy as dry, comfortable seating for sailing in light air; the sturdy aft thwart extends forward into the boat and acts as a perch for when bigger wind requires weight to counter the boat’s heeling.

The Tenderly has a lug rig. It is an easy rig to handle, set up, and stow onboard should this be a tender for a larger vessel and need to have its rig fit inside. She’s also got nice bit of sail area, 62 sq ft, and needs very little hardware to deploy it: a couple of small cleats do the job for the downhaul and the halyard, which runs through a dumb sheave—a hole—in the masthead. The head and foot of the sail are lashed to the yard and boom with 1/8″ line. I suppose one could add a jam cleat to the aft edge of the daggerboard trunk for the mainsheet that could effectively free up a hand should you need it.

Aaron Porter

Aaron PorterWhile the Tenderly is well suited for solo sailing, the CLC web site notes it has “plenty of sprawling room for two adults or a bunch of kids” while under sail.

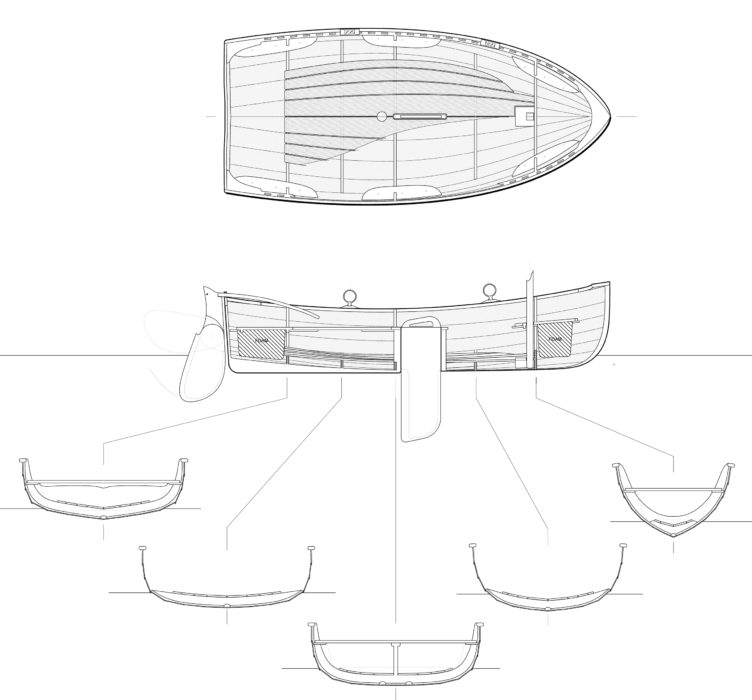

In Harris’s Build-Your-Own Tenderly class each of the seven students began their own boat on Monday and the following Saturday had the assembly complete to take home for finishing. The Tenderly kit employs CLC’s LapStitch construction method, which eliminates the traditional setup of molds on a ladder frame, so builders can quickly assemble the hull around three full frames and two partial frames; tabs on these pieces fit in precut slots in the planks to assure proper placement and alignment. The transom, quarter knees, and breasthook are installed after all of the planks have been stitched together.

Anne Bryant

Anne BryantThe LapStitch hulls go together quickly. The serpentine line aft of amidships is made up of the interlocking puzzle joints that join the plank sections.

The seven boats were well underway when I visited on day two, and the builders, most of them beginners, had already gone from a stack of kit pieces to stitched-up hulls. With the hulls flipped upside down, cyanoacrylate glue, dripped into the laps between stitches, would hold the pieces together when the wires were removed and before epoxy could be dribbled into the laps between planks. On the third day the hulls were flipped upright and given the first epoxy fillets and a layer of fiberglass on the interior up to the top of the fifth strake.

Anne Bryant

Anne BryantFiberglass is cut into wide strips to fit between the frames. The ‘glass on the inside covers five of the seven strakes; ‘glass on the outside covers four.

On day four the hulls were flipped and the bottom four strakes were ’glassed with 6-oz cloth, and the skeg and bead wales were epoxied in place. Builders installed the daggerboard trunk, center thwart and mahogany inwales, outwales, and spacers on the fifth day and finished the interior installation on the sixth. The boats were then ready to take home for paint and varnish and putting the sailing rig together.

The class was an accelerated process with long days in the shop; a builder working at home on the sailing version with daggerboard trunk, rig, rudder, etc. could spend about 150 hours building the Tenderly. The 250-page building manual is geared for the amateur builder and has many color photographs and well-thought-out instructions.

Anne Bryant

Anne BryantThe Tenderly will fit in the bed of a full-size pickup truck. State laws may limit the how far a load can project (4′ is common) and may require flagging.

With a hull weight of 100 lbs (130 lbs rigged), the Tenderly was an easy two-person lift to get it into a pickup truck; the 52″ beam gave just enough clearance between the walls of the bed. A dolly made it possible to move the boat around solo.

Anne Bryant

Anne BryantWith a cart, the Tenderly is easy to move around singlehanded.

Empty and with the daggerboard up, the Tenderly only draws a few inches, which is great when you’re launching from a rocky beach. It hovered lightly in very thin water, and as I hiked a leg up to get aboard, then shifted my weight across the gunwale, it was stable even though I didn’t plant my foot directly in the middle of the floorboards. As a cruiser who appreciates a dinghy that is easy to load, board, and launch from a beach, I find this high degree of stability a necessity.

Anne Bryant

Anne BryantWhen rowed solo, the Tenderly picks up speed quickly. The cap on the daggerboard slot helps keep the rower’s seat dry.

I rowed the dinghy over to the dock and it took off like a shot with just a couple of strokes. I think the flat bottom, sharp entry, and light construction were working with me; it responds quickly and well to turning strokes when approaching the dock or making a sharp turn.

Anne Bryant/Clint Chase

Anne Bryant/Clint ChaseWith a capacity of 425 lbs, the Tenderly can take three on board and still maintain good freeboard for rowing.

The wind was light when I headed off from the dock under sail. The Tenderly moved right along and I immediately felt safe and sound as I tacked, even though I didn’t shift my weight speedily to the windward side. The Tenderly’s stability was forgiving through my quick tacks, and it stood up as I took my time to move from the lee. The lug rig doesn’t go to windward exceptionally well, but this is a daysailer for leisure and fun and the sailing performance is perfect for that.

Aaron Porter

Aaron PorterThe standard kit includes a mast step and the daggerboard trunk; the optional sailing kit includes CNC-cut plywood for the daggerboard and rudder, blanks for the spars, and a Dacron sail.

The next day, I went out again with Andrew Breece, the publisher of WoodenBoat. I sat in the aft thwart and Andrew sat at the forward rowing station. With two people aboard there was good trim and balance, and the dinghy hummed right along.

We rowed out to Andrew’s yawl, MAGIC, to pull the Tenderly along for a while to see how it towed. Andrew said that he could feel very little drag as we towed the dinghy at about 2 to 3 knots while leaving the mooring field. We increased our speed to about 5 knots, and to feel the drag for myself, I pulled on the painter to see how hard it would be to get the Tenderly closer. It was sitting high in the water and came without complaint or too much effort.

courtesy of Chesapeake Light Craft

courtesy of Chesapeake Light CraftUnder tow, the Tenderly behaves itself and runs true.

When we returned the Tenderly to the dock, there were a few people looking to try it out. Our friend Megan picked up another school instructor, Clint Chase, to bring him back to the dock from a mooring he just tied a skiff to. He did the tricky shift from one small boat to the other, then leaned over the Tenderly’s gunwale to retrieve his gear from the skiff. The Tenderly’s stability kept the maneuver from being awkward or dicey. Megan rowed from the forward station while Clint, a tall gent indeed, sat aft. Well balanced, the Tenderly picked up speed despite the load. Megan didn’t have a problem staying on or changing her course.

Anne Bryant

Anne BryantThe forward rowing station maintains the boat’s trim while it’s being rowed with a single passenger.

We weren’t able to get our hands on a manual-recommended 2-hp motor. Given the smooth towing and the nice balance while rowing, I’d say that a bit of speed and some weight aft is going to be just fine.

courtesy of Chesapeake Light Craft

courtesy of Chesapeake Light CraftThe Tenderly is rated to take an outboard motor of up to 2.5 hp.

The Tenderly is a boat that is easier to build than some of CLC’s other kits, performs extremely well, and is a stable pickup truck of sorts, able to cart around your guests and your provisions. All of us here at WoodenBoat who got aboard it are still talking about how much fun we had. The Tenderly is a stout, seaworthy, and accessible design.![]()

Anne Bryant is WoodenBoat’s Associate Editor.

Tenderly Dinghy Particulars

[table]

Length/10′ 0″

Beam/52″

Weight, bare hull/100 lbs

Weight, rigged/130 lbs

Payload max./425 lbs

Sail area/62 sq ft

Outboard/2.5 hp, max.

[/table]

The Tenderly is available as a kit ($1,699) and as full-size plans ($125) from Chesapeake Light Craft. Add-on kits include sailing components ($1,199) and floorboards ($215).

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Question, would a junk rig go to windward better? I am not a sailor but I am getting drawn to these small boats (Swallows and Amazons) I guess.

What a cool boat! Already built the Passagemaker that I am really happy with or I would build the Tenderly. Next project is Pocket Ship!

14′ or 15′ would be PERFECT for beach cruising. 10′ is perfect as a tender.

Please, John Harris, PLEASE, PLEASE, PLEASE, design and produce a kit for a 14′ version of this boat!

John’s done it again. Easy to build, sails and rows well, and has good stability for kids or a family.

What a great little boat. A 425-lb load rating for a 10′ boat is amazing. She would be a great boat to row or sail around Ventura Harbor. I think I may just have to build one.

I would love this boat in a 12′ – 14′ version. 10′ is a bit small for the wife and me, as we exceed the carrying weight rating.

Other than that, it checks all our boxes.

Long oars I noticed, which is OK if there’s not too much wind on the high freeboard. Beamy for stability and great for load carrying as a tender. I also like the broad thwart for a strong daggerboard casing. I’d have one of these if I owned a larger yacht. Which may well happen next Autumn (April in Tasmania, where I live).

Very interesting reading and video. I live in Tasmania, Australia, and just about to build my first boat; so far I’m trying to chose between the Tenderly and Jimmy Skiff.

Regards, Lesley