Low gray clouds and fog hung in the hills above Port McNeil, an isolated town on the northeast side of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, and the jade-green water of Broughton Strait didn’t show a ripple. A curtain of dark conifers lined the shore and a bare, logged hillside hulked in the distance. Every inch of space of ROW BIRD, my 18’ Arctic Tern, was stuffed with gear, food, water, art supplies, and books. It was early August, and over the next six weeks, I would row and sail some 350 nautical miles through British Columbia’s Inside Passage back to the United States.

Photographs by the author except as noted

Photographs by the author except as notedI wasn’t used to rowing with a heavy load—seven gallons of water and three weeks’ worth of food—and the going was slow, but the scenery near Near Port McNeil was so striking that I didn’t mind.

After I launched at a campground between town and the Nimpkish River, the clouds broke up and thin strips of blue sky appeared. ROW BIRD glided through the shallows, gliding over a meadow of eelgrass. The tips of my long green blades were just inches beneath the surface; rusty rock crabs and finger-sized fish darted at the approach of the boat’s shadow. Reaching deeper water, I rowed toward the jumble of buildings and boats that crowded Alert Bay, the village lining the edge of Cormorant Island, 1-1/2 miles away.

At the north end of the bay, a First Nation’s longhouse, as big as a barn, was covered with the black-and-white stylized painting of an eagle perched atop a skeletal fish. Several cedar totem poles with orca, wolves, and human figures painted in bold red, green, and black stood nearby. I spent the afternoon walking around the island, and that evening I anchored just offshore of the longhouse. I unrolled ROW BIRD’s cockpit cover and stretched it between the masts; I arranged my foam pad, sleeping bag, and mini pillow on the floorboards. Black turnstones—stocky, white-bellied shorebirds perched on splintery pilings—kept me company with their shrill chirps until dusk. Exhausted by a busy first day, I quickly fell asleep.

Edye Colello-Morton

Edye Colello-MortonThe wind shifted from hour to hour, so I frequently changed from sailing to rowing. Fortunately, the balanced lug sail was easy to set or strike.

I awoke in the morning to a fog so thick I could barely see the shore 300’ away. I stowed my bedding, transformed the cockpit into a galley, and cooked a breakfast of oatmeal with dried apples. When I peered out under my cockpit tent, I saw nothing but a dingy white haze and heard only the deep bellow of ships’ horns farther offshore. I got under way and crept along close to the shore, but when one particularly loud horn inexplicably seemed to be getting closer and closer to the shallows, I tied up to a dock. A break in the fog revealed the source: a seven-story-tall cruise ship that was anchoring in deep water just a few hundred feet away.

When the fog lifted, I rowed east along the upper reaches of Johnstone Strait into the Broughton archipelago through the churning currents in Blackney and Whitebeach passages. In the fluky wind filtering between islands and along channels, I changed from sail to oar frequently as I navigated through a few dozen of the archipelago’s hundreds of forested islands, tree-capped islets, and bare rocks. I measured time now only by the tides and the amount of daylight available, and because I wouldn’t be returning to my starting point near Port McNeil, there was no need to think about when to head back, only where to go next.

At the north end of Vancouver Island, dense fog dominated the mornings. Here, just south of Mound Island, I waited for it to lift.

I explored the intricate shorelines of the Broughton Islands, poked around rock gardens, and slid into small coves. A few dozen yards off Mound Island, a 3/4-mile-long wooded island nestled in the south end of the archipelago, I used my Anchor Buddy to keep ROW BIRD off a stone outcropping almost as big as a baseball diamond. At its top was a shallow basin filled with salt-marsh plants and succulents like lime-green pickleweed with tiny salt crystals under its plump stems. Intricate horseshoe-shaped patterns of blue-gray lichen clung so closely to the rock that they appeared to be painted on.

I could have spent my whole trip wandering through the archipelago, but I had a loose itinerary that included 35 stops. I had allowed for a few relaxing zero days, as well as weather or tide delays, but felt I had to move whenever weather and currents were in my favor, meaning I was neither rushing nor lingering.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

To travel eastward from the Broughtons, one option was to take on 50 miles of the notoriously windy and rough Johnstone Strait, a narrow passage so long and straight that its eastern extremity would be hidden not by islands but beneath the horizon. The passage provides limited shelter for a small boat, so I opted for a longer, more protected route through the meandering back channels along the mainland. On this calmer journey I would only need to navigate a brief 15-mile stretch of Johnstone Strait—but I’d have to contend with the fast-moving tidal currents in Chatham Channel, Whirlpool Rapids, Greene Point Rapids, Dent Rapids, Gillard Passage, and Yuculta Rapids.

I had rowed for several hours against a current in Johnstone Strait and was relieved and exhausted by the time I reached Sunderland Channel. When I found the tiniest breeze, I set sail, even if it meant moving at just one 1 knot.

A few mornings later, I was rowing in the 3/4-mile-wide channel between the Lady Islands and Turnour Island. Since dawn, the only sounds I’d heard were the gentle splashing of my oars and the occasional guttural cackling of a raven, but that calm was pierced by the loud “PFFFFT” exhalation of a humpback whale that had broken the glassy surface of the water just a few boat lengths to starboard. The whale was as long as a school bus and could have been quite frightening, but it just rolled on its side, extended a 12′ long pectoral fin upward, and promptly disappeared.

Many of beaches along the Inside Passage are composed of stone and pebbles. A white shell beach, like this one in the Mist Islets of Cracroft Island’s Port Harvey, is a good indication that the site was once a First Nations village.

The next day, leaving from the placid waters of Lagoon Cove on the north end of East Cracroft Island, I rowed through The Blow Hole, a 130-yard-wide channel between Cracroft and Minstral Island that’s known for strong winds that funnel through the gap. I encountered only a modest headwind that followed me as I turned south between the steep, forested hillsides that surround Chatham Channel, the first of six tidal rapids I’d need to traverse.

Near Port Harvey, on a rare clear morning, the reflections on the water changed from pink to a deep blue. It was 7:15 as I was getting ready to depart from a beach near Port Harvey after spending the night at anchor.

I tried sailing against the headwind, but found myself making ground on one tack and losing it on the other, making it to Chatham rapids later than I expected. I turned on my marine radio and looked around for other boats. Seeing none, I headed east in the narrows with almost 2 knots of current in my favor. About halfway through, I saw a flash of red through the trees. I saw it a second time, but I wasn’t sure what I’d spotted on the far side of the bend until the radio came alive.

“Tug heading west up Chatham Channel,” a voice said. “This is motor vessel ENCHANTED SEA. We’re heading east. What can we do to keep out of your way?”

“We’re triple wide,” the tug’s captain replied, indicating the he was in one of two tugs pushing four barges, “It would be appreciated if you could spin a few circles above the rapids until we pass.”

“Roger that.”

Under oars alone, it was a challenge for me to turn ROW BIRD around and buck just a couple of knots of current. As the tugs and barges came into view, I doubted there would be enough room for me to stay safe between their likely course and the jagged, barnacle-covered rocks in the shallows. I spied a tiny cove, barely twice the width of my boat, on the Cracroft shore, a few hundred feet downstream. I floated into that small refuge, just as the tugs and massive barges labored by leaving, to my relief, virtually no wake behind them.

When I spent the night at the Port Neville dock, my boat was, as usual, the smallest. The other mariners were curious about me and my travels, which often resulted in much-appreciated invitations to dinner.

Over the next few days, I covered about 30 sea miles almost entirely under oar power, and transited Johnstone Strait, Sunderland Channel, and Whirlpool Rapids in the middle of Wellbore Channel. The northwest winds that I’d read were typical in this area never materialized, despite daily weather forecasts issuing warnings for a strong northwest wind.

Edye Colello-Morton

Edye Colello-MortonUnder calm conditions, ROW BIRD is easy to steer standing up. During long days in the boat, I took every opportunity to change positions.

As I rowed west along Cordero Channel and approached Greene Point Rapids on the northeast side of West Thurlow Island, I expected funneling winds to push me through the gorge-like passage. The rippling rivers of water pushed with the flood tide, waving kelp, and swirling back-eddies were the only signs of movement for the first few miles. Eventually, a westerly wind rose just enough for a sedate downwind sail through the end of the rapids; it petered out at the east end of East Thurlow Island, just before I reached the 600’ government pier at Shoal Bay. I cleaned the hull in the afternoon and then spent a sociable night at the dock there with cruisers who had arrived aboard several big motor yachts.

When I built ROW BIRD, I used topside paint on the interior and exterior. Worried that keeping topside paint submerged for weeks on end would damage it, I dried the boat periodically, as I did here at Shoal Bay, and scrubbed the bottom to rid the hull of growth that would damage it.

Underway again at dawn, the coal-black water reflected the low clouds overhead as I rowed toward the final trio of rapids—Dent, Gillard Passage, and Yuculta—strung one after another along a 3-½-mile stretch of Sonora Island’s east coast. I had planned to complete one rapid per day, slipping through each one as wind and current allowed, stopping for a night in between. I went through much faster. I arrived early enough that I rowed against the last of the opposing tide and passed through Dent Rapids as soon as slack started. Surprised to see that I’d made it to the Gillard Passage rapids just as the tide was turning in my favor, I forged on, taking Innes Passage, the 250′-wide channel tucked behind ½-mile-long Gillard Island.

Just 1/4 mile south of Gillard I entered Yuculta Rapids, where two hulking sea-lion bulls cavorted in the water. I rowed into an eddy and slowly pulled out my camera, thrilled as they came closer. Then, like a growing crowd of rowdy school boys, three more bulls joined them and I felt I was becoming the subject of their chasing game. Worried one might get the idea to leap aboard, I charged away into the heart of the rapids. It was just past slack, and a tongue of bubbly water down the center of the broad channel showed the safest and least obstructed route. ROW BIRD was jostled and turned here and there, but I drew on my experience with whitewater rafting to hold a steady course downstream.

Once clear of the main current, I pulled into a small cove on the rocky east shore of Sonora Island. I landed on a patch of white shell beach where I found a cascading freshwater stream surrounded by logs and lush green sedges. I checked for bear scat and prints, and seeing none, stripped off my sweat-soaked clothes and stepped in for a chilly bath and laundry session. It was pure relief to be clean again, despite the long strands of algae that clung to my hair and clothes. From the safety of the cove-nestled stream, I watched logs and woody debris in the tail end of Yuculta churn beneath the flanks of the surrounding mountains.

During the two weeks I’d been out, I hadn’t encountered another self-propelled cruiser, but I was hoping I’d cross paths with my friend Dale, who was participating in the Barefoot Raid, an informal race for sail-and-oar craft. I studied the race itinerary I’d jotted down on a scrap of paper before I’d left home, and realized that with a small change from the route I had planned, I could intercept the fleet on the northwest side of Cortez Island.

With this hopeful and loosely planned rendezvous on the horizon, I rowed into the lazy backwaters of Háthayim Park and spent a zero day cleaning salt off the gunwales, mopping out the bilge, organizing my supplies, and relaxing.

A wide variety of production and custom-built boats made up the Barefoot Raid fleet. At night the racers gathered around the mother ship POOR MAN’S ROCK.

The next day, I ghosted south 2 miles to rock-fringed Carrington Bay, also on the northwest coast of Cortez Island. The fastest of the racers had already arrived and were at anchor. A few stragglers, Dale among them, tacked all the way in a dying breeze to join the rest of the fleet. I tagged along and soon all of the boats had surrounded POOR MAN’S ROCK, a two-story workboat that followed the racers and served as the Raid’s sweep, cookhouse, and party spot. It was large enough to hold several boats in its cargo bay and 20 Raid sailors on its deck.

In the morning I joined the raiders as they continued on their clockwise circumnavigation of Cortez Island. We made the 1/2-mile crossing to West Redonda Island, tensely waited out a gale warning in a cove, and then plowed south flanked by the steep, forested hills along Lewis Channel. On the third day, the group headed west around Cortez and I continued south, crossing to the mainland’s Malaspina Peninsula, and the town of Lund. It was the first time in weeks I’d seen cars on a road.

I spent a restful night in a tidal estuary near Powell River while a storm blew through Malaspina Strait. I anchored in shallow water so ROW BIRD would settle on mud during the night, allowing hours of peaceful sleep.

I followed the mainland coast for another 15 miles, resupplied in Powell River, and continued toward the Strait of Georgia, a vast body of water covering nearly 2,400 square miles. Each morning I listened to the marine forecast, trying to make a cautious plan to cross safely from the British Columbia mainland to Vancouver Island. The forecast covered such a wide area that it was hard to know what I’d encounter within the narrow band of the strait where I’d make the crossing.

Malaspina Strait was protected by Texada Island from some of the influence of the adjacent Strait of Georgia, but being over 2-½ miles wide, it was choked with chop and confused swells that splashed aboard ROW BIRD. The one saving grace was a northwesterly 15-knot wind that pushed me through the lumpy conditions to Pender Harbor, where I would start the first half of the 20-mile crossing to Vancouver Island.

Humpback whales were a common sighting. The white cloud in the center is the exhaled mist from the whale that had come up to breathe.

Leaving the crowded harbor the following morning, I was excited to get back to open water and the freedom to move without constantly looking out for faster-moving motorboats. From Pender to Lasqueti Island was about 11 miles. I put on my sun hat and slathered myself with sunscreen. To row at the quickest pace I could before the wind picked up, I dropped the masts into the boat. I had rowed barely an hour when the tide must have shifted, because the water became so thick with short chop that it felt as though I was rowing through syrup. My normal 3-knot rowing speed dropped by half.

Later in the day a tailwind filled in and I set sail; wind waves combined with the chop, creating a lumpy 2′ following sea. ROW BIRD seemed to push the water like a bulldozer instead of cutting through it. As the wind strengthened from a gentle breeze, little whitecaps began to appear in the distance. Normally, I’d reef my mainsail when the wind approached 12 knots, but I pressed ahead under full sail. ROW BIRD bounced along, taking spray over the bow, but with the ballast of 7 gallons of drinking water and all my gear on the floorboards, combined with the steadiness of the wind, the boat felt docile and the tiller was light in my hand.

Hours later, the 8-mile crossing of Malaspina Strait was behind me and I passed Texada Island. After another 3 miles, I reached the craggy south end of Lasqueti Island. Its black volcanic rock jutted out into the strait like the broken furrows of a giant plow. I had a 1:20,000-scale chart for the islands, so I knew where Squitty Bay was, my destination for the night, but I couldn’t see its narrow entrance. I dropped the sail and poked cautiously into crevices in the southern shore by oar, aware that an errant wake could bash me against the rocks. Finally, I saw masts sticking up above a steep stone outcropping, and found the crooked 30-yard-wide entrance. ROW BIRD glided through the sheltered water toward the government dock, where I found a spot just big enough among the 10 local boats occupying the rest of the space.

Sheltered by two long ridges of rock, the water around the dock was smooth enough to see a reflection. I fell into conversation with James, a local shipwright working on a wooden sailboat moored there. He’d been living in the islands and exploring them in craft large and small for most of his life. I told him about my journey, and he suggested a route across the western 8-mile crossing of the strait that would avoid a National-Defense torpedo test range southwest of Lasqueti and provide some protection from waves by threading through a series of house-sized rocks and small islands close to the mainland.

Squitty Bay was surrounded by a provincial nature park, and feral sheep grazing among the smooth-skinned madronas and rough-barked junipers kept the grass and shrubs under the trees so low that it looked like it had been mowed. I spent two days relaxing, sketching, and waiting for the right weather window. Early on the third morning, I climbed a 200’ hill that looked over the strait. Smooth water spread to the south of the island; to the west, where I was bound, dark ripples marked the open water separating Lasqueti from Vancouver Island.

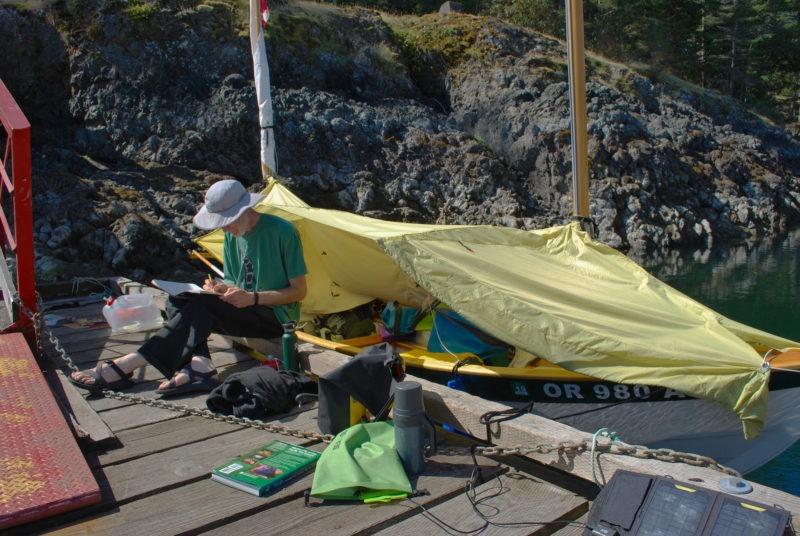

At Squitty Bay, I slept comfortably aboard the boat, my accommodations for more than 30 nights during the cruise. The canopy, here opened on the starboard side, is a two-layer cockpit tent. Its outer layer is waterproof ripstop nylon, and the inner layer is breathable Sunbrella.

The forecast called for a 5- to 10-knot northwest wind, so I anticipated a fast and mellow crossing. I rowed out of Squitty Bay, negotiated around a tug towing a log raft the size of three football fields, then passed from the smooth water into the first of the ripples I’d noticed from the hilltop. In the distance, Vancouver Island was so far away it looked like a thin ribbon of green on the horizon, in spite of the 4,000′-high ridge running along its length. Once I was under sail, the water became lumpy, and a confused swell from the north slapped ROW BIRD on her starboard side. Every third or fourth wave sent spray over the bow that left a salty film on all my dry bags and lines.

Half an hour later, the hull hissed as ROW BIRD bounced through the chop, leaving a frothy wake astern. Seven miles into the crossing, I cleared the Ballenas Islands, two 1/2-mile-wide islets that sit 3 miles from Vancouver Island’s shore. The swell and wind had increased enough that I hove-to and put a reef in the lug mainsail. The wind turned gusty, and I had to luff the mainsail more often than I could haul it in; I hove-to again and put in a second reef. I was following the plan for the crossing that James had outlined, but the rising wind and worsening sea state was troubling. Nanoose Harbor, the nearest place on Vancouver Island to get off the water, was still about 3 miles to south, but with access limited by a military base along its shore, I was reluctant to pull in there unless I got desperate.

I scanned the chart for a sheltered landing site, but couldn’t figure out how to progress safely perpendicular to a following sea that had now built to nearly 4′. Putting the third and final reef into the sail, I tried to make my way toward a private marina I saw in a tiny cove but ultimately decided I couldn’t make it. To avoid taking on water, I had to steer away from crests breaking astern. Seawater sloshed in and out of the bilge and over my feet, but I didn’t dare stop and bail.

A strong gust made ROW BIRD round up and slam over the back of a steep wave into a deep trough. The sails hung limp for a moment, then rattled noisily. I decided to let ROW BIRD drift, hoping that conditions would moderate. I set the mizzen tight, and the bow pointed into the wind, but, unfortunately, the waves were coming from a different angle and hitting the starboard quarter. I drifted toward slowly southward toward the Ada Islands, little more than a cluster of bare rocks with reefs awash in whitewater. I clenched the tiller in my right hand, adjusting to each set of waves, wondering if the next might swamp me. I pulled my VHF radio out of my PFD pocket and switched it to channel 16. Would this be the day I called for a Coast Guard rescue?

The waves crested in crumbling white foam, lifted the boat, then slowly passed me by without breaking entirely from top to bottom. Twenty minutes later, I decided that I wouldn’t call for help as long as I could still sail, so between swells, I hauled the mainsail back up, loosened the mizzen sheet, and turned ROW BIRD downwind. She surfed, swerved, and ducked between waves, and as I approached Stephenson Point at the entrance to Departure Bay. In the lee, the wind and waves abated but I had to steer away from an approaching ferry, and in the bargain slid over a reef near Horswell Rock, scraping the centerboard. When I slipped behind Jesse Island, the sails suddenly went limp, and with the ordeal of the crossing over, I felt lightheaded and hot. I peeled off my damp drysuit and collapsed onto the thwart. When I regained my strength, I rowed into a marina in downtown Nanaimo, where the high-rises loomed over the shoreline. I went to check in at the front desk, and exhausted and ravenous, I asked where I could find some pizza. The harbormaster immediately produced a partially eaten pie from behind the desk. “Take as much as you want,” he said.

Two days later, I left Nanaimo and continued southward. Using a pair of range markers, I slipped between Vancouver and Gabriola islands via False Narrows. This signaled the entry to the Gulf Islands and cruising in civilization where there were ample calm anchorages, marinas, and sand beaches. The days that followed were like a vacation rather than a wilderness expedition. I rowed and sailed in protected waters where a multitude of islands prevented much fetch from building, and stopped frequently in small towns for luxuries such as ice cream and fresh baked pastries. No longer did I think about my stores or the presence of bears; I simply enjoyed long ambles in provincial and national parks.

The afternoons were set ablaze when the sun set, turning the sky and water fiery reds and oranges, and, as September rolled in, there were fewer boats on the water. Rainstorms indicated that the season was coming to a close. Forty miles to the southeast of Nanaimo I stopped at Saturna, a 7-mile-long island pushing into a notch in the border between Canada and the U.S. Black clouds skated across the mountains to the west and blocked the sun. As I stood on a dock at Winter Cove, rain fell in dreary streaks from gray clouds.

On the days that followed, I made my way at an easy pace through the Gulf Islands, and then crossed Haro Strait into the San Juan Islands of Washington.

Under clear skies, a chilly westerly wind drove me across the San Juan archipelago to Orcas Island, where I left ROW BIRD at a marina for a few days off the water. I spent two nights at a friend’s house, grateful for the shelter as thunderstorms or low clouds rolled in each evening. Being indoors was starting to feel appealing.

My friend Andy had brought my car and trailer from home, parked them on the mainland, and came by ferry to Orcas to join me for the last leg of my cruise. After being alone on my boat for over a month, it felt good to have some company as we wound through the remaining islands.

We spent a damp night camping on Lopez Island’s Spencer Spit, a popular marine park, and got underway in the morning, headed east for Thatcher Pass, a ½-mile-wide gap between islands on the thoroughfare to and from the mainland. A hide-and-seek fog covered navigation marks, waterways, and entire islands. Foghorn in hand, we crept around Decatur Island to the safety of the cove on the west side of James Island.

I lingered on the edge of James Island in the San Juan archipelago. Even in the still air, the fog banks formed and dissipated quickly.

We tied ROW BIRD to the public dock there and climbed the wooded trail to a ridge where we hoped to see east across Rosario Strait to Anacortes, 3 miles distant, but it was lost in the fog’s dull-white void. The strait is a dangerous crossing, with strong currents, long fetches, and a north–south shipping lane crossed by a busy east–west ferry route. I’d never attempt it in fog, and even if it were to lift, we’d have to wait for the turn of the tide to slow the currents in the strait. We were stuck, at least for the night, on James. Andy got busy with his phone, making arrangements for the unanticipated absence from home and work. But for me, the fog provided the chance for another zero day and a welcome excuse to savor a final day of cruising, my 37th away from home.

Late the next morning, the fog had cleared, and with Andy navigating in the stern, I rowed, somewhat reluctantly, the last few uneventful miles across water that shimmered like rippled satin.![]()

Bruce Bateau, a regular contributor to Small Boats Monthly, sails and rows traditional boats with a modern twist in Portland, Oregon. His stories and adventures can be found at his web site, Terrapin Tales.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Great little story. I am in the the Pacific Northwest just finishing up my boat and preparing to leave for the greater far north. I love stories about small-boat cruising, as I started off that way too.

Inspiring reading, properly tempered with reminders that you take the good weather with healthy doses of bad, and days of solitude can easily be interrupted by moments or hours of terror. Sounds like time well spent!

It was great to meet you for coffee in Sidney, Bruce, and now it’s great to read the rest of the story in more detail.

Glad you made it past that long stretch of Johnstone Strait north of Sunderland Channel without mishap. It’s quite a slog when there is no wind, as Tim and I found out in 2016 going the other way.

Great writing and pictures, Bruce. Chris and I met you at our sailboat DAUPHINE on the dock we shared in Nanaimo. We’re the ones that charged up all your various batteries overnight. You told us the story of that wild crazy ride in the storm when you almost called for help. We can attest to how nasty that wind and waves were—we were severely pounded by them when we headed into the Georgia Strait and we turned around and came back inside. We left Nanaimo US-bound, a day behind you, and we looked for you along the way but never saw you again. Congratulations on completing an epic adventure. So glad you made it safely the rest of the way.

Great story. Very challenging to think of doing such a trip.

Every trip is a series of small steps. Some of them start well before the journey. There is a parallel thread about some of those details over at the WoodenBoat Forum.

Great adventure Bruce. I haven’t the good fortune to explore the waters of the Northwest yet. I’m jealous. Thanks for bringing us along.

I enjoyed your trip. Glad you made it back to share it with us. How do you get your “selfies” while on the water?

I have plans to build the Arctic Tern (actual paper plans in hand, that is), but was also considering the slightly larger Sooty Tern. Was the Sooty Tern ever a consideration for you, and if so, do you wish you had built that instead of the Arctic Tern?

The Sooty is a great boat too. It is a bit more spacious and possibly faster due to its length. I’m happy with the Arctic Tern—as you can see from this article, it can really go places and carry plenty of food and gear. If you are looking at the Sooty, I’d consider how much rowing you will do and your strength to move the extra weight.