John Carswell retired to Jekyll Island, a 7-1/2-mile-long barrier island on the coast of Georgia. With gentle slopes of white sand on its Atlantic coast and creek-laced salt marshes on its western side, Jekyll is surrounded by shallow water. When John and his wife Dorothy relocated there, they brought a boat with them, a Princess built in 1932 by the Thompson Brothers Boat Manufacturing Company of Peshtigo, Wisconsin.

Photographs by John and Dorothy Carswell

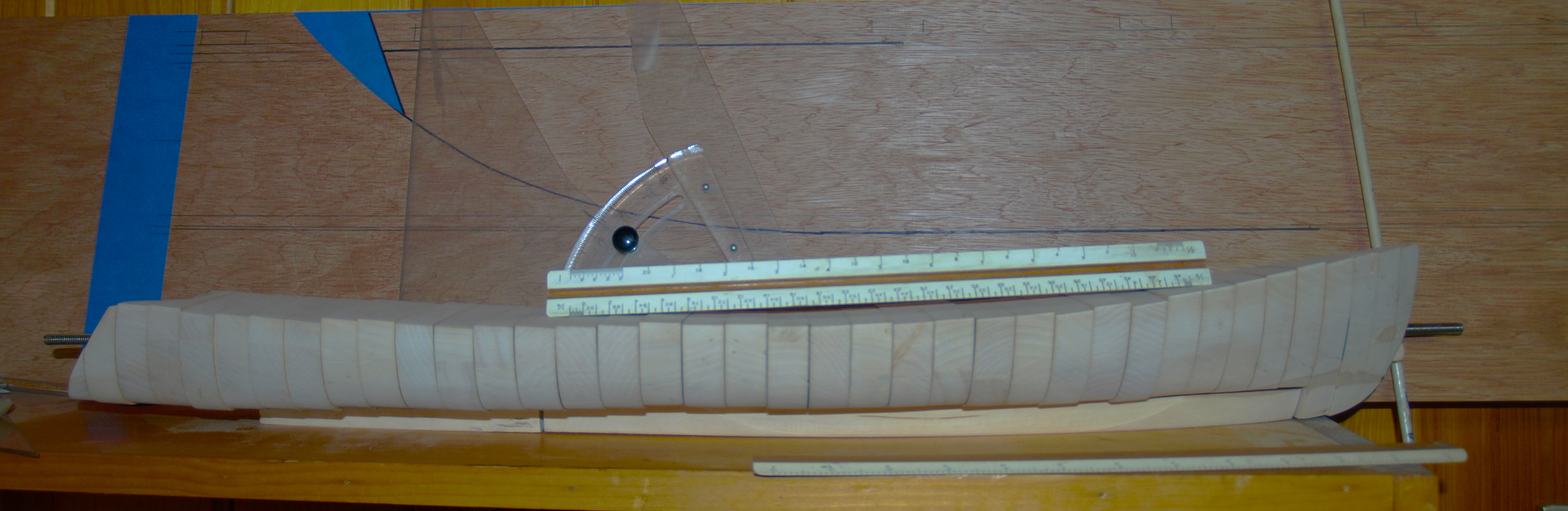

Photographs by John and Dorothy CarswellJohn began by carving a half model made of 38 vertical transverse lifts. The method is uncommon but is a direct route to a section drawing. The sections, somewhat loosely arranged here, are set on a separate horizontal piece for the box keel. He put each piece on a scanner and a print shop scaled the images up and printed them full size.

John had been rowing an aluminum johnboat for five years when he bought the aging Princess in 1985. It was far prettier than the johnboat even though the long-neglected cedar-on-oak hull had been sheathed outside with fiberglass, which was peeling away from the strip planking, taking the green paint with it. The interior varnish was cloudy and the oak frames were black along the punky keelson. John rowed GREEN HERON, as he named the boat, for five years on the lakes of central Florida and later, after a move to Washington, D.C., another 10 years on the Potomac River and its tributary, Piscataway Creek. John estimates he rowed GREEN HERON between 3,000 and 4,000 miles.

John cut the paper patterns out, traced the outlines onto ¼″ plywood, and cut them out to make molds. The time and money he saved on the flimsy plywood cost him many hours in the long run. It was a struggle to keep the molds from shifting as he built the hull’s framework over them. “I kept trying to make it work when I should have started over,” he commented. “The day I finally lifted the frame off the form and cut the 1/4″ plywood into little pieces was a day of relief and revenge.”

The boat was already hogged and leaking when he brought it to Jekyll Island and, in the five years he rowed her there, the hull deteriorated to the point where it required bailing four times for every mile traveled. After 80 years of service, GREEN HERON was beyond saving. In 2012, John armed himself with a saw but he couldn’t bring himself to put his old friend in the dumpster; it’s still under the eaves at the back of his house.

The structure of steam-bent oak frames was lifted from the molds and readied for planking. The tunnel for the propeller called for some frames bent to very unusual shapes that required a second steaming for the one half of the frame after the other side was secured in place. The box keel and the deadwood for the prop shaft were put in place after the frames were bent.

John wasn’t about to give up on rowing. For decades it had provided the conditioning he needed for a troublesome lower back. He decided that he would build his next boat. He had a shop and tools, but beyond working for a while framing houses, he had no real woodworking experience: “I just fixed old things,” he says, “I did not build new things. I was most definitely unprepared; I didn’t know how to sharpen a chisel.” And though he had fixed at least a dozen old boats, he was at a loss as to where a new one begins. He bought books, among them Building Classic Small Craft by John Gardner and started reading WoodenBoat. The study in itself was in some ways as therapeutic as rowing: “After a couple of years of retirement, my brain needed adventure as much as my body needed a rowboat.”

The 5/16″ sapele strip planks were glued only to each other and not attached to the frames. John applied only two strakes each day—the first in the morning, and the second in the evening after the epoxy had cured enough to hold the first in place.

He was drawn to the Whitehall type, imagining it as easily driven under oars as GREEN HERON, and likewise easily equipped with a sliding seat, but larger, capable of taking his son fishing. His recalled that his son suggested he should consider having a motor “because eventually I would get too old to row home.”

The hull’s strip-built shell and its framework were built as separate pieces. After removing the framework, John applied fiberglass to the inside of the shell.

Browsing through back issues of WoodenBoat, John was intrigued by Robb White’s 2006 article, “Rescue Minor: A shallow-draft motorboat.” White lived in south Georgia and, like John, needed a boat well suited to those shoal waters that extend south from Jekyll Island and into northern Florida. Photographs in the article show his 20′ adaptation of the original William Atkin design speeding along just a boat length from a sandbar in water so thin that the bottom is clearly visible. Another photo shows the boat with its box keel resting flat on the intertidal flats, with one blade of its propeller just visible above the sand, the other blades hidden by a hollow in the hull.

With the hull elevated with a hydraulic engine hoist, the protection the box keel and the tunnel provide for the propeller and rudder is clearly visible.

Atkin had designed the Rescue Minor for plywood construction and a hard-chined hull; White strip-built his version with complex curves instead, and incorporated a distinctive tumblehome stern. The plywood version would have been much easier to build, but John was taken by White’s curvaceous interpretation: “I did not worry much about the fact that Robb White had built dozens of boats and I had built zero.”

SKIMMER is quite at home in her thin south Georgia waters and rests between tides on her flat box keel. In the distance, over her stem, is the Sydney Lanier Bridge, which connects Jekyll Island to the mainland.

Rather than working from plans—they were available for the Atkin design, but not for the White—John started with a half model he carved, not with waterline lifts but with a horizontal stack of bread-slice sections.

The sliding seat is a shop stool. Its base, made of rock maple and hidden beneath the floorboards, rolls on 4″ wheels.

SKIMMER, being a lot of boat for a solo rower, isn’t fast under oars, but John rows to keep in shape, not to get from place to place.

The generous accommodations provide plenty of room for guests.

SKIMMER has two transoms: an inner one that gives the hull its watertight integrity, and an outer one built as a grating that drops down like a landing craft’s bow ramp. John used to slip over the side of GREEN HERON to go swimming on the Potomac, then clamber back aboard over the transom. That was 30 years ago; John opted to build SKIMMER with this easier way to get back aboard. Like GREEN HERON, SKIMMER was outfitted with a sliding seat—rolling, actually, on 4″ wheels—and oarlocks and 10′ ash oars salvaged from GREEN HERON.

After serving for two years as a rowing vessel, SKIMMER got her auxiliary power, a 13.5-hp diesel, neatly fit into a box that serves as the skipper’s seat.

John rowed SKIMMER for two years while he saved money for her inboard motor. When the time came, he bought a marinized Kubota 13-1/2 hp diesel and installed it under an engine cover that also serves as the driver’s seat. The instrument panel is neatly tucked away in the keel, and the starboard side of the engine box is equipped with a removable whipstaff for steering.

It was John’s son who thought that the boat John was going to build should have power as a backup to rowing. Skimming briskly along, John couldn’t help but be pleased with the suggestion.

John usually launches SKIMMER in the Jekyll River on the west side of the island and motors upwind or up current for a few miles and then rows back with the elements in his favor. SKIMMER isn’t fast; John can row about 2 miles per hour at 12 strokes per minute, but he’s out for exercise and the pleasures of the inland waters and the marsh. And while White’s Rescue Minor could do 22 knots, SKIMMER, heavier and with less power, will do just 10 knots, but as with his rowing, John is in no rush to get anywhere.

The drop-down grating transom is an elegant means of stepping aboard with dry feet.

The grating also provides a safe and easy way to climb back aboard after a swim. It easily supports John’s weight without pulling SKIMMER well out of trim.

John did very well for a first boat, especially for building one from scratch, and SKIMMER naturally draws compliments like “beautiful” and “a work of art.” But John isn’t inclined to let even the well-deserved praise go to his head: “It’s nice to hear, but I think it is mostly the varnish they see. It takes some education to appreciate the beauty of wooden boats, at least it did for me. The pleasure is in the fair curves, the scarf joints, the handles on the swim platform, that stout ipe post.” Building his first boat was neither easy nor quick. “I paid for my ignorance with a lot of hours,” John recalls. “I’ll have to live a long time to row SKIMMER for as many hours as I spent building it, but that’s okay.”![]()

Do you have a boat with an interesting story? Please email us. We’d like to hear about it and share it with other Small Boats Magazine readers.

Comments:

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.

Truly inspirational. Congrats!

John,

What a great design and project!

I was a big fan of Robb White, his expertise and humor.

Billy Atkin, joined later by his son John, designed a number of boats with the box keel. He called them Seabright skiffs. The smallest one I’m aware of was a 17′, with many in the 18′ to 24′ range, and even some to serve as shallow draft tankers (300′ or so) for use in WW II. In fact, Rescue Minor was intended for rescuing downed airmen, though I don’t know whether it was ever put to that use. Atkin said the original Seabright skiffs were fished off the shallow, exposed beaches of the Jersey shore. The originals used the box keel even before the introduction of power.

A few were round bilged, both smooth skinned, and lapstrake, but most were chine hulls, though usually not for plywood planking (too many compound curves). The Rescue Minor came along when waterproof plywood was still a new material. Atkin always claimed these hulls were good for decent speed (up to 17 mph) with low horsepower. The 17′ I mentioned above called for only a 5 or 6 hp engine. I once owned the plans for that boat, either from How to Build 20 Boats or The Rudder, and I always admired it. Sadly, that magazine with its plans went missing years ago. In those days, the magazine articles almost always gave enough information to build the boat right out of the magazine.

Most of the Atkin Seabright skiffs were published in MotorBoating magazine; later, the boatbuilding articles were bound together in hardcover volumes. I own several of these, though again, a few have wandered off. 90% of the plans were by the Atkins. Though a few of the designs now seem very dated, especially power boats, many would still be worth building. One design that was rendered in fiberglass in the 1970s (you could buy just the hull) was originally printed in MotorBoating. That was a 38′ double-ended ketch called Ingrid, a beautiful boat. There is one even now in Port Townsend advertised on Craigslist.

One of the most beautiful sets of line drawings I’ve ever seen was for a 25′ double-ended sloop called Eric Junior. I still do occasionally see one of these boats around.

An absolute beauty!

The Seabright skiff design still lives on in the lifeguard boats used on the beaches up and down the coasts of the US. Now made of ‘glass instead of wood, they sit upright, resting their box keels, on rolling logs just touching the surf as they await the next rescue.

As for Skimmer, as I am enamored with electric propulsion, I would have been very tempted to drop either a Pod from Torqeedo or Epropulsion in place of the diesel. They might have the range at speed the engine would have, but would be much lighter and more simple to operate.

Other wise, Bravo! I love the tumblehome and the cleverness of the drop down stern. You do not need to be older or have reduced mobility to see the advantages of such a set up.

Cool story, cooler boat! …

Robb White’s Rescue Minor had a keel cooler if I remember correctly. Any details on that for SKIMMER?

Congratulations on a wonderful build.

It’s a wet exhaust. I built a two-chamber water lift muffler that works very well; you can’t hear the exhaust. (The little Beta-Marine two-cylinder makes enough noise with its clackity-clack valves.)

Great article about a great guy who spent his career helping disabled veterans.

A wonderful boat. Congratulations, John.

John Atkins’ Happy Clam has intrigued me for some years now and I have often wondered why more boats of this practical design have not been built.

I have obtained a 30.5 cu. in. diesel 1-cylinder of 9 HP continuous and have ideas! Fizz boats are O.K. but they are very expensive to run and even deep -V’s are not so much fun in even small chop. I’d rather enjoy the ride.

This article is an inspiration. Well done, John Carswell.

Ah, “Happy Clam.” That was the name of the design that was in the old magazine (can’t remember whether “How to Build Twenty Boats” or “The Rudder.” 17′ long as I recall. I think that was the smallest of the box keel boats that Atkin designed.

Have you built it yet? Why not?

What an amazing story and an awesome boat. Happy to see you enjoying the fruits of your labor.