François Vivier originally designed the Seil 18 in 1988 for a group of sailors from Nantes, a region of France through which the Loire, the country’s longest river, flows on its way to the Atlantic Ocean. They wanted a boat suitable for rowing and sailing on rivers. The design was intended for glued-plywood construction, but about 150 were produced in fiberglass by Canotage de France before the company went out of business in 2007.

When Tasmanian Adrian Levings bought the Seil plans some years ago, they came with a full set of Mylar templates for “pretty much everything,” including the box-girder building frame, the molds and bulkheads, the planks, rudder, and centerboard. Vivier’s study plan for the boat included drawings with all the component parts laid out on sheets of plywood to allow the most economical cutting. Today, there are many companies around the world (including in the USA, UK, and Australia) that produce CNC plywood kits, and Vivier can provide electronic CNC cutting files.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorWhile cutting gains on the plank-end laps is called for by the plans, this Sei has the laps left proud at the transoms.

The hull is built upside down, on a 12″ × 16″ box-girder strongback made from 3⁄4″ chipboard. It is the length of the boat and is angled at the ends for the transoms. Two supports installed under the strongback hold it at a comfortable working height and have angled outer edges so that the whole structure may be tilted 45 degrees to either side to allow for easier planking. On top of the strongback, amidships, there are four bulkhead supports, and near each end is a mold. The building frame is completed with the addition of two longitudinal pieces on the centerline, which establish the curve of the middle plank (referred to in the plans as the sole). A gap between these pieces accommodates the centerboard trunk.

The bulkheads are 3⁄8″ plywood, and where they extend above the thwarts as frames they are reinforced with 3⁄4″ upper frame doublers. Adrian beveled the bulkhead edges according to the information on the Mylar templates, and then temporarily bolted them to their chipboard supports, which were already installed on the strongback. Both transoms were made up of two layers of 3⁄8″ plywood, and Adrian temporarily fastened each of them to the angled ends of the building frame and the centerline longitudinal chipboard pieces. The centerboard trunk—3⁄8″ plywood, sheathed in epoxy and ’glass on the inside faces with spacers and reinforcement in celery-top pine—is glued and screwed in place between the middle two bulkheads.

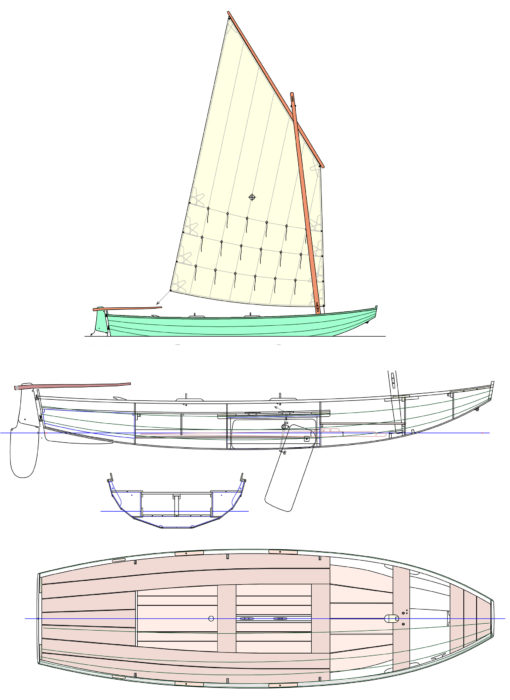

The Seil 18’s 108-sq-ft boomed balance lug has an advantage downwind over the optional loose-footed lugsail.

Each of the hull planks is made up of three scarfed pieces (the study plans also offer finger joints as an alternative in the case of CNC-cut kits). There is no conventional centerline component—keel or keelson—but the middle plank, which gives the boat its narrow flat bottom, is of 1⁄2″ plywood, the extra thickness being used for additional strength. After Adrian had cut the centerboard slot into the bottom plank, he glued it to the transom, frames, bow transom, and centerboard case (he applied plastic tape to the edges of the molds to prevent adherence there). He then installed the remaining 3⁄8″ plywood planks (four each side). Throughout the planking process, Adrian planed the plank edges to the correct bevel to accept the adjacent planks in situ. He temporarily fastened the planks with screws and large flat washers—none of the planks needed twisting or edge setting.

Once all the planks were fitted, Adrian applied epoxy fillets on the outside of the hull between the edge of each plank and the face of its neighbor; and then sheathed the hull in 10-oz ’glass and epoxy up to the lower edge of the sheerstrakes. He finished the exterior with two-part polyurethane paint. Finally, Adrian freed the bulkheads from their strongback supports to release the hull so that he could turn it over.

Adrian stripped the box girder and then built supports to cradle the upright hull at a comfortable working height. He began fitting-out the interior by installing the gunwales. The plans call for oak, sapele, mahogany, or Douglas-fir; Adrian used celery-top pine. Each gunwale is laminated in four 3⁄4″ × 1″ pieces. The first piece had a 3⁄8″ rabbet machined into it so that it could be fitted on the inside of the planking and cap the end-grain of the plywood sheerstrake; the second piece went on the outside of the planking, and the last two to the inside face of the first. He then fitted the celery-top pine transom knees, fore and aft (the plans specify oak, acacia, or iroko).

Both rowing stations have stretchers to aid more powerful rowing, but they are removable so they can be stowed, out of the way, when sailing. Raising the pivoting rudder blade reduces drag when rowing.

The plans call for foam buoyancy in various parts of the boat, but Adrian decided to fit the sealed compartments with round plastic access hatches. There are seven such compartments in total: a central one at the bow and three on each side; one between the mast gate and the forward rowing thwart; one under the side benches between the two rowing thwarts; and one each side of the sternsheets. The compartments are constructed with 3⁄8″ plywood with the listed support framing members. Supports made of 4″ strips of 3⁄4″ plywood, set on edge just outside of the perimeter of the floorboards, have angled notches to accept 1 1⁄2″ dowels that serve as the rowing stretchers for the two rowing stations. The forward station straddles the centerboard trunk, and the stretcher is made in two separate pieces. The notches offer each rower two stretcher positions.

For the thwarts, seats, and floorboards, the plans recommend red pine, spruce, Douglas-fir, and larch (hackmatack). Adrian used 3⁄4″-thick cypress (macrocarpa) for the center section of the sternsheets and forward sole, while for the aft parts of the side seats he used gray ironbark, and for the 1″-thick thwarts and mast gate he used celery-top pine. To fasten these components, he epoxied stainless-steel threaded inserts into their bearers to allow for easy and frequent removal without deteriorating the wood. He coated these and the gunwale and knees with Deks Olje D1.

The designer shows the centerboard and rudder blade made from two layers of 1⁄2″ ply, but Adrian chose to make them from strips of 1″ celery-top pine glued together. Discussions on the WoodenBoat Forum revealed a consensus that “solid wood was more robust as long as it was laminated with opposing grain pieces and sheathed appropriately.” He filled a 6 1⁄4″-diameter hole cut into the end of the centerboard with lead shotgun pellets bedded in epoxy and sheathed the outsides of both the rudder and the centerboard in 10-oz ’glass and epoxy.

The plans for the Seil 18’s transom include a notch to port for a small outboard and a smaller circular notch to starboard for sculling.

Vivier offers two alternative sail plans: a 118-sq-ft loose-footed standing lug or a 108-sq-ft balanced lug with boom. Adrian opted for the latter, again guided by the WoodenBoat Forum “about sail twist and control,” and because he had used such a rig on a smaller pram dinghy he had previously owned. The plans call for spars made of northern pine, spruce, Douglas-fir, or larch, with the mast stock glued up in three layers. Adrian made the spars from salvaged Douglas-fir—the mast is hollow; the boom and yard are solid. He thinks he didn’t hollow out the middle of the mast’s three laminates as much as the design stipulated, and so it is a little heavier than intended, but nonetheless it is easy for one person to step and unstep, ashore or afloat.

The Seil is a fun boat to sail. It has the momentum of a bigger boat, and tacks easily and with no threat of getting caught in irons, an important quality for a boat without a jib that could be backed to help the bow around. It is very stable, which is particularly important to Adrian: he has a 12-year-old son and is “navigating between keeping him interested and not giving him a fright.” It is also remarkably directionally stable: a couple of times I secured the tiller amidships and didn’t touch it for a while: she held her course nicely, despite variations in the wind strength. In Vivier’s study plans there is an option to create a large flat sleeping platform (using the thwarts and floorboards) so that one or two people can spend nights on board under a tent (although Adrian has no plans to do this).

The Seil 18’s sternsheets extend to the forward rowing thwart. There is plenty of room aboard for six, the design’s maximum capacity.

Adrian bought used 14′ oars from a local rowing club and shortened them to 10′, the length specified by Vivier. The Seil weighs almost 600 lbs, so it was no surprise that, when rowing, it takes a bit of effort to get it moving, but before long it starts to carry its way in a most satisfactory manner. Adrian has rowed the boat extensively—including one 2.7-nautical mile trip from the Tasmanian town of Snug to Bruny Island and back—and reports that it is better to leave the rudder in place with the tiller tied on the centerline for directional stability. To reduce windage and clutter when rowing, the mast can be stowed on top of the side benches—one end on top of the aft buoyancy tanks, the other beneath the mast thwart, while the other spars can be stowed in the bottom of the boat beneath the thwarts. Similarly, although Adrian does sometimes sail his boat with the oars stowed along the gunwales, in windier conditions he likes to get them out of the way in the bottom of the boat. With a second set of oars, two rowers will get a great deal of pleasure from this boat, and there is plenty of room for a crew of up to six when sailing or rowing. Although Adrian has no plans to get an outboard motor, the Seil was designed with room under the sternsheets’ removable ’midship sections in which one could easily be stowed.

The Seil 18 is a thoroughly enjoyable boat to row and sail and, I would imagine, would also behave well under power. It is excellently suited for singlehanded use, but there is plenty of room for a helpful crew member and several passengers.![]()

Nigel Sharp is a lifelong sailor and a freelance marine writer and photographer. He spent 35 years in managerial roles in the boatbuilding and repair industry, and has logged thousands of miles in boats big and small, from dinghies to schooners.

Seil 18 Particulars

[table]

LOA/17′ 8-1⁄2″

LWL/13′ 9-1⁄2″

Beam/5′ 4-1⁄2″

Draft (board up)/8″

Draft (board down)/2′ 11-1⁄2″

Hull weight, bare (approx)/375 lbs

Hull weight, fully rigged (approx)/463 lbs

[/table]

Study plans, plans, and patterns for the Seil 18 (previously the Seil or Seil 54) are available from François Vivier Naval Architect, and in the U.S. from Duckworks Boat Builders Supply.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Just a hunch, but I wonder if the ease of planking (without planks requiring twisting) is due to the pram bow. Could even be a reason that bow was developed originally for Norwegian prams.

Looks fantastic. Well done Adrian. I’m over in Christchurch, NZ, and have been looking at this design for a while, how does it sail in a chop and a breeze?

Cheers, Rich

I just returned from the Maritime Festival “La Semaine du Golfe” in Brittany, France. In my fleet number 2 (Sail and Oar) sailed close to a dozen SEIL. The conditions were on several occasions very rough with an ugly chop due to wind against the strong tidal currents. When I wasn’t too busy myself keeping upright I observed all of the SEILs doing well in these conditions, some of them quite heavily loaded.