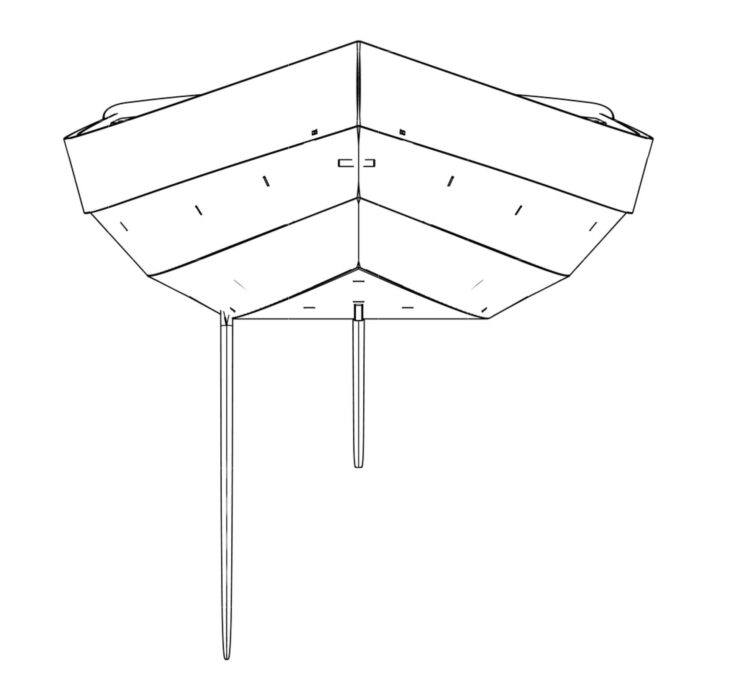

When I first saw the Scout 10, pulled up on the beach with its sail luffing, I quickly took a liking to it not for something I saw but rather for the absence of something: a trunk for the daggerboard. In most sailing skiffs, a trunk for a daggerboard or centerboard usually occupies some very valuable space in the cockpit. Neither board cares all that much where it is in the boat so long as it balances the sail rig above it. The polite thing for either one to do is scoot a bit to port or starboard and get out of the way of the crew. I’ve built three boats with offset boards and none of them has a detectable difference between port and starboard tacks.

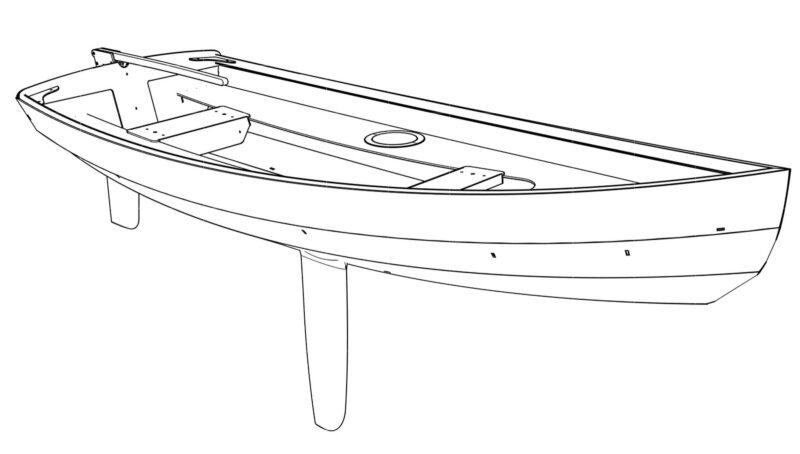

The other feature that drew me to the Scout 10 was the use of slip thwarts that can be set on the parallel edges of the side benches anywhere in the cockpit and removed when not needed. I incorporated the same arrangement in my two beach cruisers.

Duckworks

DuckworksThe slip thwarts can be placed anywhere between the side benches. Removing them opens a long unobstructed footwell that can be used for a berth.

The Scout 10 was developed in Port Townsend, Washington, by Duckworks and Turn Point Design. Their goal was to create “the smallest possible camp-cruising sailboat.” It had to be light enough for cartopping, have plenty of built-in flotation, be easy to rig, sail and row well, have ample dry storage, and be roomy enough to sleep aboard. They squeezed everything into a 10-footer with a 52″ beam. Its weight was kept down around 70 lbs with the use of ’glassed closed-cell foam in lieu of plywood for several structural elements.

The boat is available from Duckworks in kit form. The plywood and foam pieces are CNC-cut and have puzzle joints where they are required to assemble full-length pieces. The rudder and daggerboard are made of foam, cut to precise foil sections that require only finish-sanding and sheathing with ’glass and epoxy. A 120-page manual details every step of the construction with clear instructions, drawings, and photographs.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe kick-up rudder blade, with its CNC-carved foil shape, has a bungee to hold it in the down position while sailing.

The first step in the Scout 10’s construction is to make a flat work surface for assembling, gluing, and fiberglassing the foam and plywood panels. The table consists of two sheets of 3⁄4″ melamine-faced particleboard supported by three straight 2×4s spanning three sawhorses. The surface is leveled and coated with mold release or paste wax. The preparation ensures that all the pieces are flat and take fair curves during the assembly of the boat. The pieces are temporarily joined with zip ties in predrilled holes. Tabs on the interior structural piece fit into notches in the hull to make them self-positioning.

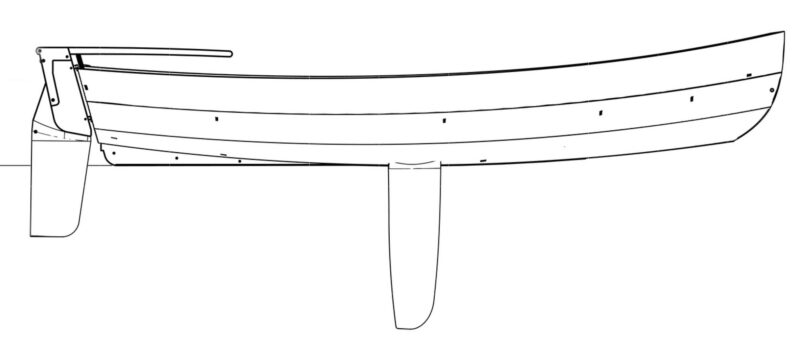

The bottom and first two strakes are joined in the typical stitch-and-glue fashion. The bottom of the sheerstrake is lapstrake and casts a shadow that provides a nice accent to the curves of the hull.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamA loop of bungee cord around the daggerboard allows it to be easily adjusted and holds it in place whether up or down. This seat, positioned for the rower, is one of two. The other seat would be set aft with its angled flange facing the rower to serve as a foot brace.

The inwale is made strong and light by boxing-in a foam core with plywood. There are 5⁄8″ holes predrilled in the plywood top and bottom pieces and after the gunwale is assembled the builder will drill through the foam in between. Phenolic tubes with a 1⁄2″ inside diameter inserted into the holes, epoxied in place, will accept the 1⁄2″ shanks of standard oarlocks or, as was the case in the boat I rowed, Gaco oarlocks with the adapter sleeves. The lined holes also provide soft-shackle attachment points for the mainsheet blocks and ends and can be used to anchor arched supports for a cover or canopy.

The deck, which is composed of the foredeck and side benches, is made of 1⁄4″ closed-cell foam ’glassed on both sides prior to its installation. A slot in the deck on its starboard side provides the opening for the daggerboard trunk, which is built on the side of the footwell bulkhead that is enclosed and concealed beneath the bench. During the time I was rowing and sailing the Scout 10, I was unaware of the foam used in its construction and assumed the benches were plywood and ’glass. They felt every bit as solid.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe Scout 10 is a good size for young families with kids eager to learn to sail and row.

The movable/removable seats are more complex than slip thwarts made from straight pieces of lumber. The seat top, which is set below the level of the side benches, provides good clearance for rowing and requires some bridge-like engineering to make the 4mm plywood a solid platform. One of the flanges that provides the strength is oversized and angled outward and serves as a foot brace for the rower. Both seats are equipped with devices that clamp on the side-bench flange to keep them from slipping out of position whether serving the rower as the seat or foot brace.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamA 10″ hatch provides access to a large airtight compartment in the bow. The halyard and a powerful downhaul are both anchored on the mast so the whole rig can be dropped almost instantly. The mast has a core of carbon fiber and a silvery, abrasion-resistant outer layer of Texalium, a fiberglass cloth with an aluminum coating.

The footwell is 20 3⁄8″ × 81 1⁄2″ long and unimpeded by the daggerboard trunk so it can be used as a place to sleep although the manual cautions that it is “not a luxurious berth.” Its width is a perfect match for my 20″ × 72″ self-inflating sleeping pad. I’m 6′ tall and a side sleeper and can tuck my knees up at a comfortable angle and, if I set my back to one side, I have room for my elbows on the other side. For stargazing while lying on my back, I’d have room for my shoulders, but my elbows would have to be someplace other than at my side. Even so, as a quickly made nest, it would be welcomed by a tired cruiser for a midday rest or overnight sleep. Duckworks suggests using “a cloth, hammock or filler boards over the footwell to create a double bunk.” On three of my camp-cruisers, I’ve used the same approach and made floorboard panels that can be raised to cover the footwells. The sleeping surface provided by the hull’s flat bottom, by the way, allows the Scout 10 to sit upright on the beach.

Collection of the author

Collection of the authorThe Scout 10 comes up to speed quickly and is a pleasure to row.

The enclosed spaces under the deck can be equipped with watertight hatches. The Scout 10 I rowed and sailed had been equipped with the three round watertight hatches—two 8″ and one 10″—that Duckworks offers in its kits for the Scout. For easier access to cruising gear, I’d consider the larger rectangular 10″ × 14″ Sealect hatches that are recommended in the manual as an option.

The 58-sq-ft sail has a sleeved luff and slips over a two-piece tapered carbon-fiber mast. There is no boom, so the rig is simple to set up. The sail has four battens. The top one supports a squared-off head, which adds sail area, and the other three shape the sail and maintain its spread on a downwind run. The rudder has a pivoting blade held down with a bungee and retracted for beaching by an uphaul with a jam cleat. While the rudder will kick up if it touches bottom in a shoal, the daggerboard must be raised by hand. A bungee looped around it holds it in position whether raised or lowered.

Collection of the author

Collection of the authorIn the quick turn here, the stern snaps smartly around. The transom has two handholds for getting a sure grip for dragging or carrying the boat and also has a notch for sculling.

The Scout 10, with the sailing rig left off and just me aboard, is a bit tender but the firm secondary stability kicks in readily. I settled in quickly and enjoyed the boat’s lively, responsive feel. I could spin it through 360 degrees with just five-and-a-half strokes and make crisp turns with a harder pull on one of the oars. The boat trimmed well, with the bottom of the transom just touching the water. The skeg, fully immersed, did its duty, keeping the boat from wandering off course. The wide range of options for the placement of the seat and the oarlocks would make it easy to adjust the trim to accommodate the load and even tune the trim for upwind or downwind rowing. With a GPS measuring my speed, I maintained 3 knots with a relaxed effort and 3 3⁄4 knots at a moderate workout pace. Rowing all out, I could get the Scout 10 up to 4 1⁄4 knots. With a passenger aboard, I moved the seat to the forward end of the footwell and relocated the oarlocks to the appropriate holes in the gunwale. The measured speeds, respectively, were 2 3⁄4, 3 1⁄4, and 3 1⁄2 knots. The additional weight in the boat also nicely firmed up its initial stability.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe 14′ mast weighs just 5.2 lbs and breaks down in two pieces for easy stowing on board. The uppermost of the four battens supports a bit of extra sail area up high.

Rigged for sail, the Scout 10 was easy to manage. The sheet is led through a small block at the clew, through blocks at each stern quarter, and forward along both gunwales to another pair of blocks; it ends in stopper knots. The system allows the skipper to sit facing forward, with one hand on the tiller, and the other taking hold of the sheet by its leeward stopper knot. The boat was well behaved in the light and occasionally fluky winds I had and absorbed the puffs without requiring me to respond dramatically. The hull carried its speed well enough to get through tacks without getting caught in irons. On the new tack, the battens were limber enough to snap to the new leeward side without requiring a sharp tug on the sheet.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe Scout 10’s 58-sq-ft sail is boomless so an accidental jibe is forgiving to a crew caught off guard.

I didn’t do a capsize drill with the Scout 10, but Small Boats reader Daniel Patterson did. In his video we can see the boat coming to rest on its beam ends, prevented by the mast from turning turtle. The airtight storage compartments float the footwell above water level and when the boat is righted, the only water in the bottom is what is scooped up in the angle between the side bench and the sheer and that’s not enough to affect stability or even require bailing before getting underway again. The built-in flotation also provides support for crawling over the gunwale to get back aboard.

Common wisdom is that the size of a boat is inversely proportional to the frequency of its use, and a boat as small, light, and as versatile as the Scout 10 is likely to lead a busy life. It can be made ready for the road in short order and can explore waterways near and far whether for a few hours or a few days. ![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats.

Scout 10 Particulars

The Scout 10 is available from Duckworks in kits ranging from the CNC kit of precut plywood and foam pieces for $2,099 to the complete package with the full sailing rig for $4,299.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats readers would enjoy? Please email us your suggestions.

Chris, I’m intrigued by the “cartoppable” comment.

Weight is given as from 65 – 75 lbs. Is that all-up including spars, rigging, oars and so on?

How heavy is the empty hull without all that, which is presumably the minimum weight that one would be manhandling?

I wasn’t equipped to weigh the Scout when I had access to it. In a video produced by Duckworks it’s noted that “the bare hull’s around 80 lbs.” One of the web pages cites the prototype weighed 65 lbs.

My 18’9″ decked lapstrake canoe is a bit over 80 lbs and I regularly cartop it, right side up. I also cartop my 14′ sneakbox, which is , I’m guessing, over 100 lbs. I only lift one end at a time to get either boat on the roof rack. Boat length is an advantage. For the Scout 10, its 10’4″ length would put the boat at an angle closer to vertical when one end has been raised and is resting on the rack. That puts the greater share of the weight on the end still resting on the ground. The lift would be hardest at the start and get easier as the boat approaches horizontal and then slides forward across the back rack. If the rack is wide enough for the Scout’s 50″ beam, the boat could be set on the racks upside down. While I’m guessing that I could load the Scout on my 2001 SUV, I have to be more careful about what I subject my back to and would consider some of the DIY rack extensions to create a ramp to raise the boat safely by degrees.

Thanks Chris.

Scout is short enough that it should also go into the back of a pickup truck with the tailgate down, a much lower lift. It would leave a couple of feet hanging out, but that might be OK for a short-ish trip down to the launch ramp.

Hey Alex, below is a picture of Duckworks’ demo Scout 10 being cartopped, right side up, on an SUV to take it out to a local small boat festival. It’s surprisingly light, two people can lift it up to the top easily. And since it sits flat on its own bottom, it sits politely on a roof rack without issue.