When Erik W. was growing up in rural New Jersey, his father would take him on adventures in a 15′ Old Town canoe, fishing on small local lakes and paddling whitewater stretches of the Delaware River. When Erik entered high school, he joined the whitewater kayak team, playboating standing waves and creekboating through fast-moving whitewater in tight creeks and rivers. Those early experiences instilled a love of the water and of paddling that has never left him.

After high school Erik joined the Army and went to West Point where he trained in mechanical and aeronautical engineering. It was a natural fit for the young man who loved to see how things come together and how a design can turn into a functional, physical object. He was, he says, “the kid who took things apart, but who also built things like tree forts and pinewood derby cars.”

Erik W.

Erik W.Before DORCAS was rigged for sail, she was used as any other canoe, for paddling and occasional camping trips. Erik and his father have also ventured with her into some whitewater stretches of the Delaware River.

All things wood and floating went on the back burner for Erik’s nine years in the military, but in 2012, returning from a final tour of duty in Afghanistan, a friend suggested bareboat-chartering a 42′ Hunter sloop in the Florida Keys, and Erik fell in love with sailing.

Upon his return to civilian life, Erik set himself up making fine furniture for a living. Largely self-taught, he specialized in chairs. He was drawn to the craft, he says, because “you’re constantly trying to figure out how to do things, how to transform ideas and designs in your head into things that have beauty, purpose, and longevity. I particularly liked chairs because they’re very technical; they have to have an aesthetic, the right ergonomics, and be structurally sound.”

Erik W.

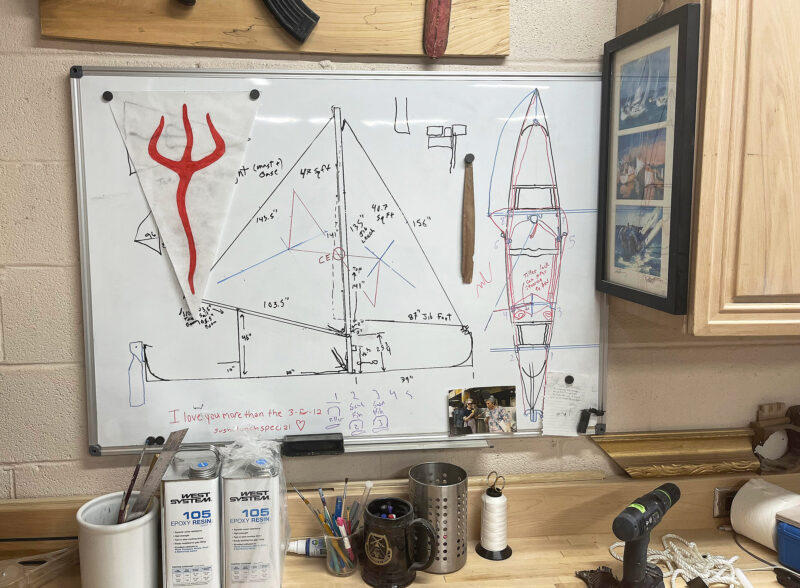

Erik W.The scale drawing that led to DORCAS’s rig was worked out on a whiteboard in the shop. The house flag—a combination of a W (the family’s initial) and a trident—is flown at the masthead whenever Erik goes sailing.

Erik ran the woodworking business with two employees for three years, but inevitably, he says, “when you turn a hobby into a profession it robs the fun. I stopped enjoying it.” He closed the shop to commissions, “entered the professional world,” and went back to having fun with woodworking. In 2017 that “fun” led to the building of a cedar-strip canoe.

It was a return to his roots. He still dreamed of sailing, but paddling was more immediately attainable and familiar. He set out to build a cedar-strip version of the 18′ 6″ White Guide, a 19th-century canoe with enough carrying capacity to accommodate himself, his wife, and then-baby daughter, Wendy. “I thought it would be good to build something the whole family could enjoy, something we could take out for two or three days and not have to come back in to restock supplies.”

Erik W.

Erik W.Before venturing out onto the water, Erik tested the outrigger (ama) set-up in the garage. The outrigger arms (akas) are tied to the gunwale mounting blocks with Dyneema line. Erik stands DORCAS in the cradle blocks when he rigs her at a launching site and has made similar cradles for the ama.

Erik began the project with high hopes and high energy. His original idea was to assemble all the parts, mill the bead-and-cove strips, set up the forms and strongback and then, with the help of two friends, get all the strip-planking done in one four-day weekend. “We worked furiously,” Erik says, “and by the end of the weekend we’d gotten half of it done.”

His friends departed, leaving Erik with half a canoe hull. Like so many builders before him, he discovered that even after all the strip-planking was done there was much to do. “There was sanding, fiberglassing, and fitting out.” Some of the construction, he says, was fun. To guide him in the process he had two books—Illustrated Guide to Wood Strip Canoe Building by Susan Van Leuven and Building a Strip Canoe by Gil Gilpatrick—but found that there was never quite enough detail to get him through. But he enjoyed the figuring out. “I don’t like the ‘paint-by-numbers’ approach to construction, so I was fine with that.”

Erik W.

Erik W.The canoe, ama, and all other parts can be transported in the back of Erik’s truck. Apart from the maststep, the only permanent fixtures that were added to the canoe were the rudder gudgeons and the stemhead fitting for the jib furler.

Along the way, Erik tweaked the design here and there. Wanting to improve the rigidity and strength of the gunwale, he increased the width of the spacers between the inwale and the hull from 1⁄2″ to 3⁄4″. He changed the decks from solid cedar to cedar strips to match the hull and installed bulkheads for additional flotation in the ends. He was glad of this last modification when, the following summer, he and his father almost swamped the canoe coming down the Delaware laden with food and camping gear. “We were well loaded,” he says, “and hit a wave train that was just too high. We would have swamped without that flotation.”

Between the figuring-out and the fit-out there was “always the sanding…so much sanding.” Faced with the tediousness of the task, Erik found himself veering away from the canoe to other “more interesting” projects and so the weeks became months, and the months became years. “I just wasn’t very engaged,” he says. “When it eventually came time to finish and name it, I was so frustrated that I chose what I thought was an appropriately terrible name, DORCAS.”

Erik W.

Erik W.The forward aka also serves as a partner to support the mast. At the port end of each aka is a small seat for hiking out. On the inaugural outing, DORCAS’s mast was unstayed but Erik decided it wasn’t stiff enough and has since added shrouds.

Despite his early antipathy, DORCAS—both the name and the canoe—grew on Erik once she was out of the shop. For the next couple of years, he used her extensively. He and his father went whitewater paddling—“We’ve only cracked her three times hitting rocks… I never forget to bring duct tape, but I guess people don’t normally go whitewater canoeing in a cedar-strip”—and Erik would take his family out for less adventurous outings on a local reservoir, making the almost 1-mile crossing to a favorite beach for picnics.

All through the build and subsequent paddling, Erik continued to dream about sailing. He snatched up any opportunity to sail that came his way. He went on a weeklong camp-cruise in Annapolis with Warrior Sailing, a program for veterans, and delighted in being part of a sailing community. He considered buying his own sailboat, looked at some 21- and 22-footers that were for sale, but realized that he didn’t want “a trailer with a big boat on it” sitting in the driveway. He also knew he didn’t want to take on the commitment of a bigger boat with all its associated upkeep and maintenance.

Jackie W.

Jackie W.The golden eyes painted on the bow of the ama were inspired by the adornments once seen on Greek triremes. Erik chose gold for the irises because “it’s the symbol of shapeshifters in literature.”

Instead, Erik imagined putting a sailing rig on DORCAS, and as he developed the idea, he came up with some design parameters: The rig had to fit inside the back of the truck. The canoe and all its parts had to rest on his truck’s cab and tailgate and be strapped down, as it always had been. The additions to the canoe had to fit in the garage, out of the way of his wife’s car. It had to be exciting but safe under sail, and he didn’t want to be hiking out the whole time. It had to incorporate an outrigger with enough trampoline area between the outrigger and the canoe for the whole family to come along for the ride in comfort.

He eventually devised and built an outrigger, ama, with a compartment in the middle for water-ballast and flotation in the ends. The curved laminated-white-ash outrigger arms, akas, are inserted into sockets on the ama and held in place by locking latches. The akas are lashed to blocks bolted to the gunwale.

Jackie W.

Jackie W.Wishing to avoid an offset tiller from astern Erik designed a system of pulleys and lines leading from the rudder yoke to a ring mounted beneath the sheet bridge. He steers with a short tiller mounted on the ring. The removable bridge is also the mount for all the running rigging lines.

“I didn’t want to make any significant changes to the canoe other than installing the rudder gudgeons, the stemhead fitting for the forestay, and ’glassing in a maststep,” says Erik. He also wanted the process of rigging the canoe to be simple and quick. “There are five lashings to attach everything to the canoe,” he says. “We don’t always put on the trampoline, but even if we do, start to finish, it can be rigged and ready in under an hour.”

To keep everything short enough to fit in the truck, Erik considered a gunter rig to keep the length of the mast down, but “it felt like there’d be too many moving parts.” Instead, he went with a leg-o’-mutton mainsail on a 14′ mast with a furling jib. In its original iteration the rig was unstayed, but on the first outing Erik realized the mast was too unstable, so he added shrouds. A leeboard to starboard reduces leeway and improves the canoe’s maneuverability.

Erik completed the rig in May 2023 and sailed DORCAS five times that summer. “I changed the rig each of the first four times, but by the fifth it seemed pretty well sorted out. Once I’m set up for sailing I’m pretty much committed, but I can still paddle her. I designed it so the forward paddler can work on either side. The aft seat is blocked by the outrigger to starboard, but I can compensate with the rudder. Plus, she tracks really well with the leeboard down. Under sail she’s very responsive. She scoots around in 5 knots of wind. I’ve sailed her in 18 knots, but I did spill a lot from the sails. There are no reef points, but I can furl the jib and she sails really well with just the main.”

Erik W.

Erik W.Seated forward of both the mast and the forward aka, the bow paddler can work to port and to starboard. The red bag to port is holding the anchor and all the anchor line. It’s attached to the gunwale with a soft shackle. When needed, the anchor is taken out of the bag and the line is then paid out, being stopped with a Prusik hitch to another soft shackle.

For Erik, the sailing rig has been a great addition to the canoe. His daughters—Wendy, now five, and her two-year-old sister, Robyn—have had a mixed response. Robyn loves it and sits with Erik at the helm excitedly shouting, “Go Daddy, GO!” while Wendy is less enthusiastic. Erik thinks she was having a bad day when she came out with him but admits that she’s also used to “just sitting around on the cushions of her grandfather’s 31′ powerboat while he cruises her around.” Not to be daunted, Erik is planning a couple of overnight trips this summer and hoping to meet up with other sailing-canoe enthusiasts at the Wooden Canoe Heritage Association’s gathering at Paul Smith’s College in New York.

As for DORCAS, she has risen from time-consuming chore to much-loved family boat. And Erik has even changed his opinion of the name. “Turns out dorcas is Greek for gazelle,” he says. “Given her speed under sail, that seems very appropriate.”![]()

Jenny Bennett is managing editor of Small Boats.

Do you have a boat with an interesting story? Please email us. We’d like to hear about it and share it with other Small Boats readers.

DORCAS looks like a great small boat that can be paddled or sailed and does not need a trailer to move it to the water. It is a great example of where less is more.

I would like to build this boat. Are there plans available?

Harry Coster