President John F. Kennedy made a speech in Houston, Texas, at Rice University on September 12, 1962. I was only nine years old at the time, but one part of that speech eventually reached me and stayed with me, as it has for most Americans:

“We choose to go to the Moon…We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.”

The president’s declaration led to Neil Armstrong, less than seven years later, making the first footprint on the lunar surface. And getting to that point was hard, even for a nation with almost unlimited resources. As individuals, we set goals for ourselves that are more modest than going to the moon, but those that are the hardest for us to achieve, no less “measure the best of our energies and skills.”

In this issue, Isabelle Heker tells us of the daunting task she took on of building a Greenland kayak in spite of her lack of skills, tools, and materials and in spite of the doubts cast by those closest to her. Dave Gibson, also in this issue, built a plywood kayak and confessed that after looking at the instructions, “I had not even started,” he said, “and I was buffaloed.”

I was also intimidated by the steep front face of the learning curve I had chosen to scale when I first started building boats. I read lots of books, gathered up the tools I thought I’d need, and made a start. I got as far as stetting the frames on the bottom of the dory skiff that was my first real boatbuilding project. A batten sprung around them showed the frames weren’t all making contact along that batten’s fair curve. I spent a week, maybe two, checking offsets, studying the lofting, measuring the frame, searching for the numbers that were causing the problem. I couldn’t find them, gave up on that approach, and decided that the only solution was to take my direction from the batten and build the boat.

Building that 14′ skiff was the most difficult thing I had done to that point. In spite of the challenges, the mistakes, and the disappointments, I often stepped back from the work, nestled in the pile of redolent oak and cedar shavings I’d swept into the corner of my makeshift shop, and gazed at the boat in wonder. The feeling of “I did that” wouldn’t have been as rewarding if the project had been quick, easy, and without suffering.

I thought the repairs I had to make to the kayak I had allowed to fly off my roof racks would have been easy. I’d made repairs before, after it had arrived seriously damaged after being air-freighted from Denmark. The new fix the aft deck required was easy, a repeat of the repair to the foredeck I’d done years earlier. But addressing the damage to the skeg and the crack in the aft half of the hull had me a bit “buffaloed” and took a lot of thinking before I could continue the work.

I had to create some new tools and new ways of using existing tools as well as invent methods for working on damage I could access from just one side. I complained to Rachel that I was having to find solutions to problems I’d never encounter again. That missed the point. The value of the exercise was not in a solution I’d never need again, but in being determined to solve a problem I’d never encountered before.

If I had taken up woodworking because I had wanted it to be easy, I would have stuck to projects that involved only straight lines and right angles. I wouldn’t have started building boats with the struggles posed by their curves and compound bevels. With each boat I built after the dory skiff, I took on more complex builds that would pose new problems to solve, knowing full well that they would at times frustrate and even annoy me, but knowing just as well that the level of satisfaction would rise with each elevation of the difficulty. To put it Kennedy’s way, the challenges would serve to organize and measure the best of my energies and skills.

In that 1962 speech, President Kennedy also said this: “We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained.” It’s no surprise that his metaphor was about boats.![]()

Update:

I greatly appreciated all of the comments sent by readers who could empathize with my story about forgetting to tying my Struer kayak to the roof racks and the damage it suffered falling onto the pavement. I finished the repairs recently and, after a two-month hiatus, got it back on the water. Here is a review of the damage:

The rudder blade was bent almost 90 degrees by the impact.

The forward end of the hull had lots of scratches.

The skeg was punched into the hull and a break along the centerline extended about 5′ forward from the hole.

These cracks aft of the cockpit were the worst of the damage to the deck.

And here is what it took to make the kayak seaworthy again:

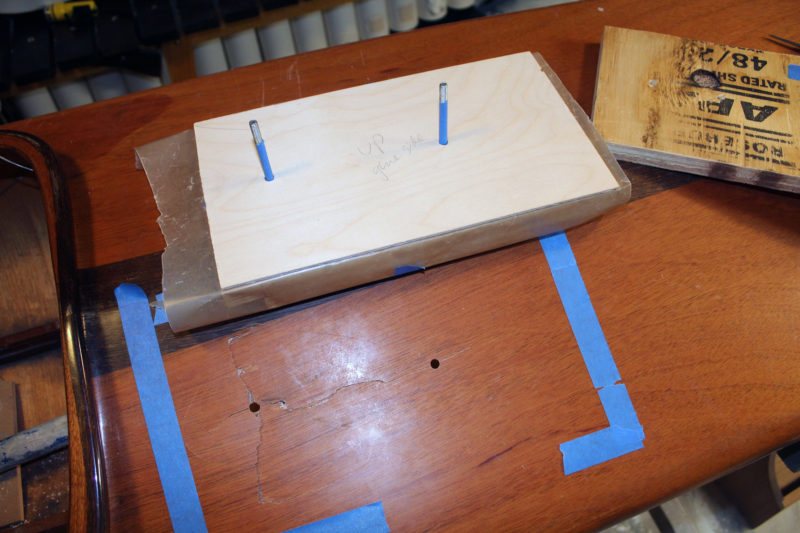

The fractured area of the deck would be epoxied to this piece of 1/8″ birch plywood. Two pieces of 3/4″ plywood, cut to the same shape and drilled through with holes to match those on the deck, would pull the interior patch tight to the underside of the deck.

Two carriage bolts pulled the sandwich together and assured that the flaps of torn plywood would all come to a smooth, fair plane.

Torn plywood edges don’t just snap back together like a puzzle pieces. The frayed fibers have to be scraped away to get the edges to align. A small pen-knife blade did the job for all of the cracks except the one here on the port side of the skeg. That fracture, right at the edge of the skeg, was at a shallow angle pointing at it, blocking access. I made a tool from 1/4″ mild-steel rod with one straight edge and one hooked. I heated each end with a torch to hammer and bend them to the rough shapes required, then filed and belt-sanded the scraping edges.

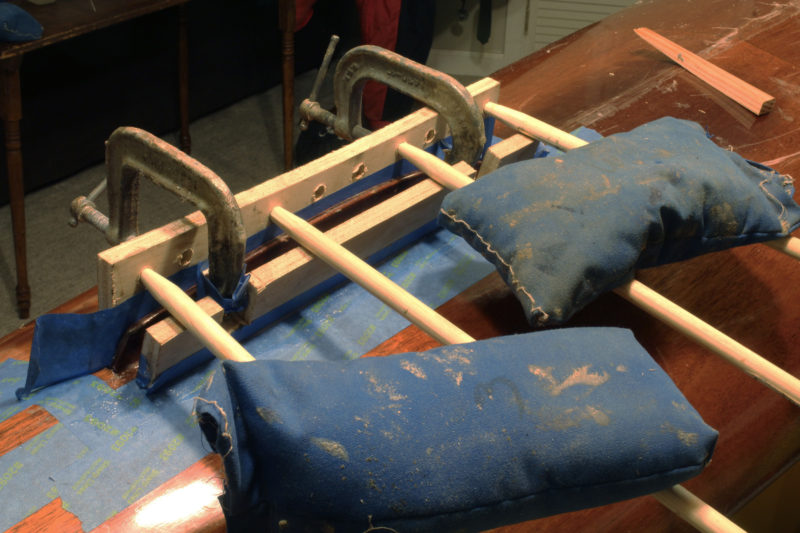

I couldn’t get the skeg to line up with both sides of the hole in the hull at the same time so I glued the starboard side first. A long stick parallel to the skeg pushed the edge of the hull flat and fair. Three short sticks, weighted with small sandbags and their ends tucked under blocks hot-glued to the skeg, applied pressure. The straps, wedges, and blocks push down on two parts of the tear that needed more force to lie fair.

For the second step, gluing the port side of the skeg, I used a variation of the same cantilever pressure system. One block of wood with holes drilled in it was clamped to the starboard side of the skeg. Another block of wood, pushed down by the sandbagged dowels, applied pressure on the hull side of the break.

And here are the results, with a fresh coat of varnish:

The damage to the bow’s underbody was mostly superficial and remedied with sanding and new varnish.

The skeg is back where it belongs, with very little mahogany missing along the breaks, and the rudder has its proper posture back.

I didn’t bother to disguise the bolt holes, filling them with white thickened epoxy instead. I’m OK with the visible reminder to tie the kayak to the roof racks.

Two months after dropping the Struer from my car, it is back on the roof racks. This time I tied it down.

Out for the first time this winter, the kayak felt and looked almost as good as new. There were few other boats out on this chilly January day. A sailboat on the south end of Seattle’s Lake Union was one of them and the only one I passed by within earshot. The skipper took a long look my way, then called out: “Nice looking kayak!”

By the way, the axis of the rudder seems very well known to me. It looks like the output shaft of a head-lamp wiper motor. In the eighties I developed this little motor for nearly every existing car. While testing, we did a lot of misuse. They survived, for example, three times the lifetime cycle completely under water. So we did the best, so you could use the shaft at your boat 🙂

Best wishes from Germany

The repairs turned out great.

Whenever I “complain” to Pat, about a problem I have encountered in a project, she says, “remember, it’s part of the process.”

Exactly!!!

Nicely done !

Great story. If it was easy, anybody could do it…

I built my boat in a 12′-wide boat shed with exposed studs in walls (boat is 8′ wide). To achieve some of the plywood bends,I utilized the upright studs with other lumber wedged in. Some bends in the bow were pretty tight and unclampable. Your repair looks great.

Just wonderful – and you’ll love the boat all the more!

This reminds of an oft-quoted comment by Nick Schade who – toward the end of his book, The Strip-Built Sea Kayak, points out the the boat is not complete until it sustained its first gouge (painful but inevitable). I’m not sure Nick had this kind of gouge in mind, but based on this attitude, you now have an immensely perfect and complete boat, and a stunning beauty at that!

Couldn’t agree more with all of the above comments, and I also know from personal experience dropping my Sam Devlin Duckling 14 off the roof of the car while trying to load it on a slope that, after the repairs, the bond between boat and owner is stronger than ever, just like the repair. Congratulations.

Wayne from Australia

I have a Wilderness Systems Arctic Hawk fiberglass Greenland-style kayak that I thought I’d spread out the cross bars on my roof carrier before heading to the cape. People told me to be wary of traffic on the Bourne Bridge. Not having much success budging them, I started out. he nagging tap tap sound I heard about 1 hour down the highway I attributed to my straps flapping, a common occurrence. It got louder and I glanced the rear view mirror in time to watch the whole kayak AND the cross bars (I kid you not) go flying into the breakdown lane of I-295 in Maine. Apparently I had budged them more than I thought. Luckily there were no cars immediately behind. An off-duty state trooper stopped and helped me load it in the back of my Volvo and I limped home.

I thought it was toast but the more I looked at the cracked nose and couple of scrapes, I realized I could epoxy that back together which is just what I did. It’s not the prettiest job but allowed me to get it on the water again. Others expected me to make a planter out of it, which I wasn’t having

Also I get bragging rights to the day my Arctic Hawk took a flying leap.

When I was putting wood together to make something called a sharpie and hoping that it would float at some time in the future, I performed what I called my “ok, give it your best shot, have a beer and remember it is wood and can be cut away” dance just before attempting a difficult part of the build. From numerous dances, experience showed: Do not use cheep beer. Only the best, and sometimes in quantity, creates the best results. Looking at your photos, I estimate you had a case to case and a half job. Well done.