I woke to the splashing of salmon leaping around MUSTELID, our 24′ by 5′ 4″ home-built, plywood camp-cruiser. Anke slept alongside me, her long hair a sleepy bronze-and-silver tangle. Two layers of sleeping bag, spread wide against the early-morning chill, rose and fell with every breath. Today, we faced a difficult test with a tide to catch. I kissed her awake. I sat up and looked around through the expansive, plexiglass windows flanking the narrow, 4′ × 8′ cabin. Salmon were launching themselves in mercurial arcs, and low clouds, dense with charcoal underbellies, obscured the dark upward slopes of Kruzof Island on either side. The more-often-than-not fog of the last week had lifted slightly, at least within the bay.

David Reece

David ReeceIn light winds, we might row while sailing if we’re hurrying to catch a tide. Here, during sea trials, we sailed under the Ljungström foresail and mizzen. The driver, our aft sail to be stepped on the outside of the transom, was added later. The boards are deployed against guards and prevented from winging out to windward by line secured to the guard ends.

We had designed and built MUSTELID as a more easily driven adjunct to our larger, engineless liveaboard sailboat. As we have aged, sailing it has become more strenuous and we hope that MUSTELID will serve as voyager and forager, allowing us to continue spending our time on the water. In outfitting the boat we were guided by the Agile Approach of software development as adapted for boatbuilding by Jeremy Ulstad, a software developer and boatbuilder:

Make it cheap.

Make it fast.

Make it work.

Make it right.

MUSTELID is a platform for exploring our approach to living aboard, rowing, and sailing. Whenever possible, we employ found, used, or common materials. On this voyage and others, we sail for months or years in the wild. We favor rugged and repairable.

We had set out on this shakedown cruise from our home port of Tenakee Springs, Alaska, on the east side of Chichagof Island. We intended a lazy, meandering circumnavigation, clockwise and totaling about 450 nautical miles. We’d arrived in Kalinin Bay on the north end of Kruzof Island a week into the trip. Trees tinted blue-green by twilight leaned almost over us, their branches draped with long, trailing garlands of yellowish Spanish moss. Extending outward from the rocky, bladder-wracked beach, a ledge of smooth granite formed the nook of our anchorage. We’d caught one of those leaping salmon in the bay for last night’s dinner, working a lane break in the lemony green macrocystis seaweed, whose small, alternate flotation pods and corrugated fronds reminded us that we were now in outside waters.

Photographs by the authors except as noted

Photographs by the authors except as notedLooking aft: the cabin’s 4′ x 8′ floor has carpet laid over foam padding, making it very comfortable for sitting and kneeling. At left is our orange folding mattress. The two pillows hold our bedding. At the back, a 2′-deep alcove serves as our galley. The rocket stove in the middle sits under a smoke exhaust hood. The two storage totes, when pulled out, provide work surfaces. At right, through the windows, our dory tender is visible rafted alongside where it stays quiet.

MUSTELID was Bahamian-moored with two of her three anchors set opposite one another. They limited swing, keeping us off the shore but within the narrow protection of the outcrop. Kalinin Bay has better-protected anchorages farther in, but this spot would save us rowing a mile and a half. We’d need to conserve our energy for this day’s effort. Rousing ourselves, we “made the bed” and stuffed our sleeping bags into oversized pillowcases. These contain the bags loosely, to air them out and preserve loft, and make for great daytime lounging. We folded the double camping mattress along the starboard wall. Our only other “furniture” is the large toolbox that serves as an inside doorstep and the plastic stowage totes that can be pulled from our compact galley alcove to serve as a table and countertops. We kneel on knee-friendly, 1″-thick foam topped by carpet.

We use simple snap-latch dogs to secure the longitudinal bench seat’s storage-locker lids. We also use one for the aft locker hatch. These simple wood-and-paracord dogs were inspired by those used in fishery tote lids. Nylon paracord acts as a spring, angled inboard of a dog’s fulcrum. The dog cam-levers the paracord into tension to snap reliably in place.

Anke kindled the fire in the wood-burning rocket stove. A paperback book provides a compact stack of kindling papers, and while we shy at book-burning, this one—a thick bodice-ripper from a free table—will not be mourned. Lopped-off spruce limbs crackled cheerily in the bright flames flickering in our rocket stove’s gaping mouth. These insulated stoves generate enough heat to burn smoke, doubling the wood’s efficiency and protecting lungs. It had taken some noggin-scratching to design and build a hood from scrap that would provide a large cooking surface and lead the exhaust to the stovepipe. In pleasant weather the stove can easily be removed for cooking outside. We prepared a hearty meal fragrant with sweet yarrow, wasabi-like sea rocket, and the rich smell of poached salmon leftovers. Soon, the percolé of water boiling against teapot’s lid and scent of spruce-needle-steam announced hot tea. As we ate, we listened to the marine forecast: southerly winds at 15 knots over combined seas of 5′ to 7′. Lumpier than we’d like, but this wind was a gift that we had waited a long week for. A southerly is a favorable departure from the prevailing southwester, which blows at right angles to the northwest run of coastline; we weren’t confident that we could sail on a beam reach and stay clear of that lee shore in sloppy conditions. That leaves contrary northerly-quarter headwinds or a dangerous, offshore easterly. This was our shot.

The morning scene here looked very much like the niche we had tucked into at Kalinin Bay. The stowed mizzen amidships leaves a small patch of sail standing. This saves lashing the boom vertically and provides a spot for hanging our anchor light.

First, we must cross Salisbury Sound from Kalinin Bay to round Point Leo. Next, we’d have a run up a pernicious coast, then turn into more protected waters via the treacherously tight and rocky Piehle Passage. It was only 16 nautical miles, anchor to anchor, but challenging at every step. At the heart of this leg are 7 nautical miles off a mile-wide, shallow, foul, and breaking shoreline, open to a 1,000-mile fetch from the Gulf of Alaska. It is liberally peppered with rocks both salient and submerged. The latter are dangerous as they are poorly charted—the whole area is marked “breaking seas”—and might only make their presence known when they thrust a rare, extra heavy swell to toppling height. They’re hard to spot. Our strategy was to ride the last of the ebb tide out of Kalinin Bay and Salisbury Sound. Then the flood would lift us along the coast and carry us through Piehle Passage at the end of the run.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

These were unfamiliar waters and MUSTELID was unproven. Despite 30-some years of sailing, we were new to small, open craft. And though we’ve often sailed open coastlines, we had always insisted on fallbacks. Navigating MUSTELID along this stretch unavoidably broke our standing rule.

We’d spent the previous night in quiet talk and restless sleep, gnawing at this first of only two exposed legs of our circumnavigation. For this one, we were sailing with confidence but considerable trepidation.

Before departing, we made a salad of leftovers: the last of the salmon, rice and lentils, handfuls of chopped wild greens, and berries. We’d spoon it cold throughout the day as needed.

We weighed anchors, hauling the cold, wet 1⁄2″ nylon rodes and even colder shots of 1⁄4″ chain, hand-over-hand. Seated at the aft station near MUSTELID’s waist, I pulled at my 9′ oars; Anke rowed with 8′ oars at her narrower, forward station. By now we were effortlessly synced to the same rhythm.

The kick-up rudder has a downhaul on the port side and swings on heavy strap hinges. The tiller is reversible and here is mounted facing aft. A bungee pulls it hard to port; the line on its starboard side leads to a whipstaff in the cockpit. The driver’s simple mast mount doesn’t pierce the deck and avoids the intrusion of water. Its outboard position allows the mast to be dropped easily. Forward of the mast is the rocket stove’s chimney cap, made from a stainless-steel dog food bowl. Rocket stoves create a strong draft, so a short stack works fine.

The whipstaff, our vertical tiller, controls the distant rudder from the cockpit. It is slotted at the rail and stands upright when the rudder is centered and is held by friction, leaving hands free for the oars. My central station and greater leverage make it my job to attend to course corrections: minor ones by oar, major via whipstaff.

With each stroke, we rolled on double-action sliding-seat prototypes we’d cobbled together from cast-off materials. The high-density polyethylene wheels had no bearings to corrode in the saltwater environment. Their wheels rolled smoothly on cleat-tracks along the longitudinal cockpit bench and locker lids.

On this cloud-enshrouded day the archipelago’s boreal rainforest was not arrayed so much in colors as in tones and shades. Subtle, layered gradients blended one into the next, as if in an old-fashioned, hand-tinted photograph. A light, morning drizzle cooled us and fogged our fleece jackets with pearlescent silvers and grays, mirroring the grumpy sky.

East and west, the steep sides of Kalinin Bay slid by, their slopes densely cloaked in the ubiquitous, climax canopy of somber hemlock and Sitka spruce. Inset from the water’s edge was a fringe of brighter, deciduous greens of red alder and rock maple. Along the water, mottled beaches of boulder, cobble, and gravel, strewn with iridescent seaweed and bone-drab driftwoods, were punctuated by dark outcrops of light-toned granitic and blue-black basaltic bedrock.

Here, at the beginning of our passage from Kalinin Bay to Khaz Head, the fog over Salisbury Sound has lifted. Set on the starboard bow, our anchor sprit makes deployment and retrieval of our main anchor easy while standing securely amidships. At left, on the port gunwale is the whipstaff for steering. The pivot bolt is tightened enough to provide friction to hold the rudder in a fixed position. We later put the whipstaff on the starboard side, a move made easy by our open-gunwale system. We are both right-handed and more comfortable steering on the starboard side.

We were fast approaching Kalinin’s opening. I owled around to peer forward and saw Point Leo across 5 miles of gently rolling water. Here, too, the fog had lifted; we would not be making this jump blind. Our GPS was aboard as backup, but we were relieved we wouldn’t need it.

As we cleared Kalinin’s mouth, our view opened wide across Salisbury Sound. Ahead, were Chichagof Island’s range of mountains, steep for all their modest height. To starboard were the islands and channels through which we’d come. Away to port, there was only liquid horizon, undulant with ocean swell.

Waves rose as high as our cabintop and their troughs spanned 100′ crest to crest, enough to encompass four MUSTELIDs laid end-to-end, but in the morning calm rowing was no harder despite the swell, and we slid along at the easy pace we knew we could maintain all day. We began to breathe more easily.

Rain came and went in turns, ranging from mist to bailable downpours. A quarter of the way across, a first frisson of wind cooled my left cheek, then stirred my hair. A light breeze picked up and up, easterly out of the sound. It was offshore, but we were committed now, and this was, for us, a rare beam reach.

Anke rowed steadily while I stood amidships to unfurl the mizzen sail. It had been wrapped close around the mast but for the small corner at its clew. We stow that bit standing, which saves lashing up its boom. As I unrolled the China-red sail, it flogged against the curdled gray clouds. I hauled the clew out to spread the sail and levered the whipstaff to bear away.

Our inexpensive masts and spars may not grow on trees, but they grow as trees. We look for shaded-out, standing, dead spruce of the right dimensions and taper, which are straight, tight-ringed, and rot-free. It can take a lengthy search to find the right ones, but it’s pleasant work.

The foresail is Ljungström-rigged with the addition of two light booms. The sail itself is identical to and exchangeable with the mizzen sail, but doubled the two sails are fixed to the mast along their luffs. For any point but a run, one sail laps the other like a closed book, and their sheets handle as one. Now, we opened the book for a large balanced sail, pulling from the bow.

A drawknife makes quick and easy work of barking and smoothing spruce trees for spars and looms. Knots are lopped flush with a hatchet and finished smooth with a four-way rasp. Rejects get cut for firewood.

Anke unfurled the twin foresails, trimmed both to port, and we steered back on course. Reaching a long diagonal into and across the swell, MUSTELID’s sampan bow shrugged spray aside and rose over the crests. We yawed some on this long slant, but smoothly and predictably.

Moving mounds of water heaped higher, even momentarily occluding the horizon. As the waves grew taller and steeper, white teeth began to show along the crests. The combers hurled themselves against the rocks in booming bursts of shattered water.

The transom-mounted sprit-boomed driver is controlled from the cockpit by a loop of line led aft through fairleads. One side is fixed to the sprit’s outboard end, and the other to its long-for-leverage inboard end. Between them, the driver can be set, backed, or fixed within a nearly 180-degree sweep. The bight-tail is cleated as one to fix position. The control lines clear the deck and no boomkin is necessary. The stowed mizzen amidships leaves a small patch of sail standing. This saves lashing the boom vertically and provides a spot for hanging our anchor light. MUSTELID’s cabin is inspired by Phil Bolger’s BIRDWATCHER. It is watertight to the narrow centerline gangway and adds immense reserve buoyancy in a knock-down. In theory, we can self-right from within the hull, important for remote, cold-water sailing. Buoyancy when awash is also provided by the watertight long bench, seat lockers, and the watertight fore and aft lockers. The cabin’s gangway is covered by telescoping hatches traveling their entire length. A 100W solar panel is mounted on the upper one.

Slowly, Point Leo rose above us from its crouch, appropriately leonine, and its mane of breakers roared at our approach. Rock faces, mineral streaked and stained in muted maroons, yellows, and carbon-blacks were now vivid above wrack-clad rocks awash in milling fields of foam.

We’d held our upwind advantage against the offshore breeze, and it was time to turn down. I pulled the whipstaff aft, and we fell off to port to parallel the shoreline.

A sudden loud whump and lurch startled us as the foresail half-jibed to open full, wing and wing. MUSTELID surged forward with its doubled power, uncomfortably pressing our hull speed. Anke quickly eased the clew outhaul and reefed four turns, and we slowed to a manageable clip.

We rounded the point at a run, the gnash and splash of water chewing stone close at hand. As if hamstrung, the breeze suddenly fell away. We were left bobbing on ocean swell unopposed by wind. We had covered 5 nautical miles in one hour, and we had rowed a quarter of that. We were an hour ahead of plan; that meant an extra hour of fair tide still ahead.

Sue Horwath

Sue HorwathMUSTELID sailed a light breeze with the Ljungström mainsail closed for windward sailing and both sheets handled as one. Both leeboards are deployed for lateral resistance.

Fortuna Strait, the 1-2⁄3-mile passage inshore of Klokachef Island, grew quiet and flat. We got our first look at Leo Anchorage, a recess in the wall of Chichagof, fronting a broad valley between verdant mountain ranges. It has good holding and is protected from prevailing winds but is rolly and exposed to the south. Not a place to linger, but a decent fallback.

We left behind the protective north reefs off Klokachef and with them, flat water. Ocean swells swept into kicked-up walls of spray and dingy foam on the reefs to starboard. With shore now close to starboard, the waves rebounded to us. What had been widely spaced and gentle slopes in Salisbury Sound were here steep, cross-hatched ridges creating interstices big and deep enough to hold MUSTELID in cupped palms, tossing us from hand to hand.

With each of MUSTELID’s yawing plunges, our oars wrenched on one side, and missed on the other. We quickly learned to time our strokes to connect with the water or to pass and commit less power to each. It was strenuous, slow going, but we were moving steadily.

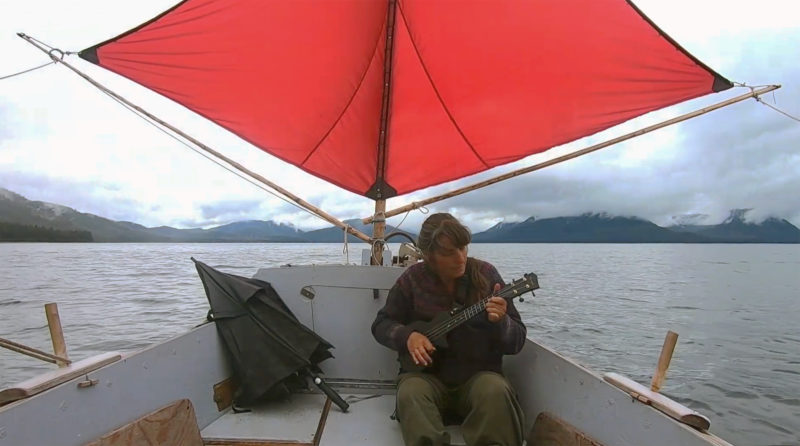

The Ljungström sails, spread wing and wing, provide well-balanced power for downwind sailing. Anke’s carbon-fiber ukulele is inexpensive, lightweight, compact, and waterproof.

After 3 miles of this, though, I felt the first pangs from muscles in my shoulders and back. I was already approaching my physical limit. We were halfway; whether we turned back or carried on, it would take the same effort either way. Anke said she was still at full strength but if I dropped out, her load would increase. I was not sure she could carry us forward alone for long. I kept rowing to help as much as I could manage.

Ordinarily, under these conditions we would find a place to anchor, but while this whole stretch off the Khaz Peninsula is shoal enough to be within reach of our anchor, it’s foul. The bottom could eat the anchor or spit it out. If the prevailing westerly came up, we’d be on a merciless lee shore. By the look of it, even without wind, it would be like spending the night in a blender.

We labored toward Point Slocum, two-thirds of the way up this outer stretch. I was trembling and felt loose in the joints. I had no cramps yet, but they couldn’t be far off. I kept pulling and breathing, a little ragged now. Anke’s tough, and while she was tired, she kept rowing.

We were drawing even with Slocum and contemplated risking one of our anchors as far out as we could reach bottom, when the wind lifted from nothing to a firm push from the south. We unfurled the sails to halfway, foresail open, and let the wind carry us foaming along.

With wind came darker squalls of rain, obscuring the rocks among which we now sailed at speed. Rain splattered on the water around us and the wind hissed in our rigging. MUSTELID was surrounded by the ceaseless roar of surf on rock and the shrill pealing of gulls.

Here at Piehle Passage we enter a cluster of small, wooded islands in an area on the chart maligned as “foul bottom.” The orange spool on the foredeck, made for long extension cords, holds 150′ of ⅜″ line at the ready for an expendable anchor and chain. The single sail and boom are set in the forward position instead of the Ljungström rig. The sheet and clew meet at a grommet that travels along the boom as the roller-furling sail is extended or retracted. By keeping the sheet and the clew anchored at the same point, the load on the boom isn’t subject to the bending force of having the two separated, and the boom can be made thinner and lighter.

We tended inshore, among breaker-marked rocks, closing to make the entrance to Piehle Passage, leading off the outer coast to more protected waters. It had been described to us many times, but no two descriptions matched. Up ahead, we could see a low island, close onshore. Its profile matched our best guess as that marking the turn into Piehle.

Anke jibed the starboard wing over with a jolt, instantly reducing the foresail’s area by half and slowing our approach. She clambered aft to sit close behind me as a particularly dark, wet, squall made dusk of daylight and poured itself upon us.

Together, we steered ahead with the wind on our port quarter. We were tired, and it took my two hands and one of Anke’s to operate the whipstaff. It felt bolted in place.

We tore close on by a boulder that reared mast-high above us, and emerged on its far side, unscathed and in the clear.

Our relief was short-lived. A raft of five sea lions that we had startled charged us while rising high out of the water. Then, as one, they dove off and away, leaving nothing behind but their foul, fishy breath.

Shaking, we turned to skirt the leeward island’s tresses of kelp, floating at their ease amid the froth of breaking water. We rounded Piehle’s entrance into the lee and all that wind and chop and churn—which we could still see and hear heaving behind us—fell to ripples and catspaws.

Spacered outwales create a strong girder to support the sheer. The gaps between evenly spaced blocks provide slots for plug-in accessories like the tholepins, leeboard hanger, and whipstaff (which can be repositioned at will). We carve tholepins from spruce limbs and make grommets from beachcombed poly-pro rope. They cost nothing, and float if dropped overboard. The oar looms come from standing-dead spruce trees, and their slender blades are shaped to shed flotsam or flipped to hook it. A leeboard is below, in its stowed position. It is shaped to be laid horizontally over the cleats to form a large, cockpit platform for sleep, work, or play. At left, the dark rectangle is one of the drain ports that dumps water should the cockpit swamp.

The entrance looked wider than we had imagined but its margins are mostly hidden. Rocks, black and jagged, popped up at random, some marked by weed. Others, we knew, lurked just under water, which was now too still to betray their presence.

Peering overboard, we could see a mixed bottom of sand, weed, and rock a couple fathoms down. Mussel blues and bladderwrack greens, starfish reds and oranges, and anemones’ waxy shades of white shimmered below.

We hung our leeboards over the side from hangers slotted into the outwale to thwart those willy-nilly gusts, which skittered us sideways in the narrow passages.

Many of the rocky islands scattered about were storm-scoured naked, or sprouted a paltry stubble weed. On others were a few stunted trees with trunks fixed in a wind-levered slant. We were not yet through the passage and still on what must be the frontlines of winter storms.

Peter Ord

Peter OrdThe four sails of our three-masted cat-ketch rig—twin-foresail main, mizzen, and sprit-boomed driver—are identical and interchangeable. A deep reef is put in the sail used for the driver.

Maze-like waterways wove and wandered between islets and islands. The chart abandoned accuracy, stating “Local knowledge is advised.” Three elongated islands we had depended on to guide us weren’t clearly identifiable in the mishmash of poorly drawn features. No elevations were given to help sort things out. We got lost.

Only blunt Khaz Head, intermittently visible, hinted our general whereabouts. With it as our guide, we squirreled into one of many havens among crumbling cathedrals of granite, basalt, and metamorphic rock. Anchored, and shore-tied to a wizened tree, we were too tired to celebrate.

We tumbled into our dry cabin, changed into dry clothes, and I hung the wet up to dry. Anke lit a fire and within minutes warmth began to soothe and loosen our tight and knotted muscles. Soon, the teapot burbled that hot spruce-needle tea was ready. We threw the last of the salad into the cast-iron frypan, added handfuls of bladderwrack, and—as a special reward—smothered it in precious curls of cheddar. Once the seaweed had turned brilliant green and tender and the cheese was dripping molten, we fell to and devoured every last morsel.

Satiated, and clumsy with fatigue, Anke unfolded our mattress and pulled the sleeping bags from their pillows while I hitched our anchor light from the mizzen boom, knowing no one would see it.

Cradled and rocked within MUSTELID, lulled by the croon of surf, Anke and I drifted off to sleep.![]()

Dave and Anke have produced a series of fascinating videos about their experiences with MUSTELID. Join them as they design and build the boat that will become their home for an epic adventure around stunning Southeast Alaska. Episode 1 explores who Anke and Dave are, how they live and what they propose for their adventure. New videos will be released each Saturday of the weeks that follow. The entire collection will be archived in the Specials section of the Small Boats Nation website.

Anke Wagner and Dave Zeiger live and sail in Southeast Alaska’s Alexander Archipelago, sometimes for years between towns, on a series of self-built boats mostly of their own design: TriloBoats, MUSTELID, and dories. They acted as caretakers at remote sites for a number of winters and work the gig economy when they must. They most enjoy sailing full and by along the Low Road, with extended stays in undisclosed locations of exceptional beauty. They document their adventures at Triloboats.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

So glad to comment on this adventure. Dave and Anke are simply awesome: ingenious and generous souls. I’m looking forward to enjoying this series on MUSTELID. And learning lots.

“…. we’d have a run up a pernicious coast …,” indeed, Dave and Anke, indeed.

What a treat to hear more about the MUSTELID adventures. I have been following their website for years and have been hoping to hear more about this adventure since Dave first wrote about it. MUSTELID seems to be an excellent platform to take on adventures large and small. Dave’s get-it-done pragmatism and design ideals of simple and failsafe solutions letting you access all the shallows and exponentially expanding a the coastline make the build and adventure seem achievable. I will be following along for this ride, so roll on Saturday and the next.

Looking forward to this series. Been waffling over a design to ply the rivers and reservoirs in my area.

Very impressive. A boat/person could spend a year between Piehle’s and Lisianski and rarely be seen. Incredible country. Hope you got a bath or two at White Sulphur, where I want my ashes strewn.

Cheers,

Bill

Hi Bill,

We totally agree, and who knows? May have such a year yet in the cards. We did get to visit White Sulphur, which lived up to its reputation… that portion of the trip will be covered in MUSTELID – Episode 10.

May your ashes be strewn a very long way down a joyous road!

Dave Z

This is an amazing story, by such a remarkable couple! Wonderful!