When I realized the car that had turned right at me was not slowing down, I tried to speed up, but the camping gear I carried on my 10-speed weighed it down and I was unable to get out of the way. The car hit me broadside and the impact launched me over the handlebars: I did a somersault in mid-flight, the top of my head just glanced the pavement, and I landed on both feet in a deep crouch. I stood up, stunned that I wasn’t injured aside from a road rash on my left elbow. My bicycle didn’t fare as well. The rear wheel was badly bent, and the left crank arm was pushed to the opposite side of the frame so that both pedals were on its right side. Somehow my left foot had come free of the toe clip and strap and my leg wasn’t broken. I ran after the car, which had stopped a few dozen yards away.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorOn the approach to Salt Lake City, Jim (seen here) and I had to endure a hot, 40-mile stretch of road across the Great Salt Lake Desert.

On August 1, 1977, my best friend Jim and I started riding from our hometown, Edmonds, Washington, headed for the Grand Canyon. We rode 800 miles to Salt Lake City and Jim was missing his new girlfriend, Jane. He decided to take a bus home, and I couldn’t blame him. On August 10, I continued south on my own. I’d gone just a few miles and was still within the city limits when the elderly driver with impaired vision ran into me. After my brief suborbital flight over Utah asphalt, I had no idea that the collision would (eventually) lead to my dream job—which I couldn’t even have imagined at that point: working as an editor for WoodenBoat. At the time, I was just happy to be uninjured. The driver paid for a replacement bicycle and, two days later, I was back on the road and pedaled another 1,400 miles before arriving back home. That was my last bicycle tour.

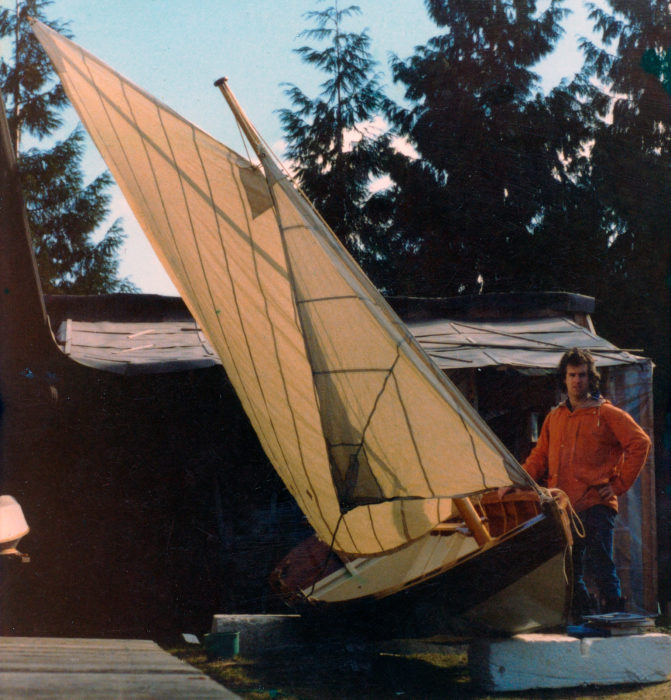

At the same time that I was finishing the dory skiff, I sewed its sails from cotton boat drill, as recommended by Pete Culler in Skiffs and Schooners. The structure behind the boat is the shop in which I built the skiff. My father had the garage occupied with his racing-shell repair work, so he let me build an extension on the back of the house over the concrete pad I’d used for basketball.

Before that ride in the summer of 1977, I had done a lot of backpacking, but I had hit the limit of what I could carry and how long I could stay out. Eventually, the pressure of a 70-lb load on my pack’s hip belt had caused nerve damage that left my right thigh numb for decades. I shifted to bicycle touring, but after getting hit I was no longer at ease sharing the road with cars and gave that up, too. I still wanted to pursue traveling under my own steam, and small-boat cruising seemed the best way forward. A boat could carry more gear than I could haul on my back, and waterways had room for me to stay well clear of motor-driven traffic.

After I finished the skiff, I dismantled my boatshop and left one corner of it around the garage door at the back of the house for Dad to use as an extension when he was working on 40′-long four-oared racing shells. The workbench beyond the bow of the skiff, with the red chair on it, was roughly built and meant to be temporary, but I’m still using it 45 years later.

I studied maps of Puget Sound and British Columbia and was taken by Knight Inlet, which follows a crooked 78 miles from the B.C. coast to some of the 7,000′ summits of the Coast Range. I needed a boat but I couldn’t afford to buy one, so I decided to build one. After reading a handful of boatbuilding books, I settled on the 14′ Marblehead dory skiff. I started building it in the fall of 1978 and launched it on a rainy spring day in 1979.

Our neighbor across the street gave Dad an old trailer for a V-bottom boat and the rollers weren’t at all suited to the skiff. I set a piece of 1/4″ plywood over the rollers to protect the hull. Dad’s 1965 Chevy Sportvan was the tow vehicle.

While my plan had been to row and sail to Knight Inlet that summer, I had grown uneasy about my lack of experience. I had also discovered that building the skiff was a challenging endeavor, and far more satisfying than the means to an end that I’d thought it would be. I put aside my vision of cruising and talked my father into letting me build a boat for him. I spent the next year building a Chamberlain gunning dory.

There was a boat ramp on the Edmonds waterfront, but I wanted to launch the boat at Skinny Beach where I had spent my summer vacation days all through secondary school. I also preferred having the dory carried bow-first to the water by my family and friends rather than backing it in on a trailer.

After launching Dad’s boat in the summer of 1980, I felt obligated to finish what I’d started with the dory skiff before I let another year slip by. I launched from Mukilteo, Washington, and headed north. After a week of rowing, Knight Inlet was coming up just as I’d settled into the rhythm of rowing day after day and enjoying the wilderness as it unfolded around me. The rowing was tiring but didn’t leave me aching at the end of the day as backpacking had, and not a single boat had run over me. I wanted to keep going and opted to follow the Inside Passage northward. I managed to row and sail 700 miles to Prince Rupert, just shy of the Alaskan border, and stopped the day after the mild summer weather had given way to dangerously strong winds.

Inspired by the orphan girl played by Paulette Goddard in Charlie Chaplin’s movie, Modern Times, I christened the dory GAMINE. It was a rainy windless day, so I left the sails at home, but brought the mast for the Cunningham house flag I’d made as a copy of the flags flown by five generations of my family before me.

When I got back home, my parents showed me a copy of Nor’westing, a local boating magazine, which had been published while I was away. In it, presented as the first article of a series, was a letter that I’d written to friends of my parents who had been eager to hear about my trip. They were also the owners of the magazine. I was shocked that my casually written letter had made its way into print and, worse yet, that a few thousand readers were expecting the rest of the story from me. To spare myself further embarrassment, I had to become a writer.

After my first row aboard GAMINE, I took my parents out. The sou’wester Mom is wearing is one I made of canvas coated with GacoFlex, a rubbery paint Dad had used when he reskinned a wood-and-canvas canoe.

I didn’t do any more writing for publication until 1987 when I sent Sea Kayaker magazine an article about building a paper canoe and paddling it 2,500 miles from Québec to Florida. Still wary after my first experience with publication, I fussed over the writing endlessly until I was sure it was squeaky clean. It was squeaky clean, apparently, and was published verbatim. Two years later, I got a phone call from the founding editor, who was planning to retire. He had remembered my clean copy and invited me to succeed him. I knew nothing about magazine production, but I took the chance. It turned out well and I held that job for 25 years.

Two years after launching GAMINE, I set out from this stretch of Puget Sound on a course that took me 700 miles north along the Inside Passage and beyond that to a career devoted to boats and their stories.

In the last few of those years, sea kayaking had passed the peak of its popularity and in 2014 the magazine had to close. Shortly after the last issue went out, I got an email from Matt Murphy, the editor of WoodenBoat, with the offer to edit Small Boats, a new online magazine that WoodenBoat Publications had in the works. The path that began with getting hit by a car in Salt Lake City had finally delivered me to my dream job.

Many of my classmates in high school and college seemed to know from an early age where their life trajectories would take them, but I didn’t have that gift of foresight. Perhaps being raised as a rower by a father who was himself a rower got me used to not seeing where I was headed, and the notion that the path would only make itself clear while I was looking back. As it turned out, I didn’t need to know where I was going to arrive where I wanted to be. Sometimes we have the good fortune to be guided by happy accidents.![]()

Chris,

A delightful story about your summersault into a life in boats. I’m glad that old guy didn’t end it for you before you even got started.

Andrew

Wow, this brings to mind my own bike accident. Not during one of the many bike tours thankfully. Just a ride to work on road undergoing perpetual reconstruction. Done in by those massive side mirrors of new at the time Ford truck-sized SUV.

I emerged relatively unscathed, certain the Bell helmet played a role. Writing wasn’t on my horizon, but I did happen to take up sailing soon after. Oddly last sticker for boat was ’93, still at my now ex wife’s house.

I subscribed to Sea Kayaker from 1996, when I first arrived in the Northwest and began kayaking, through its final edition in 2014. It taught me a great deal about kayaking and touring, led me to try building a kayak in 2001, and that in turn led to building five (so far) sailboats. But the most valuable thing the magazine did was to publish a long article in nearly every issue about a sea kayaking expedition that went bad—a few even fatal—with detailed analysis of the kayakers’ mistakes. I have no doubt that these articles saved lives.

Chris deserves enormous credit for his contribution to the sea kayaking community.

Chris, the two white shapes on the wall, behind the red chair??

Well, since you asked, those are swan wings. I’d found a dead swan near the railroad tracks that run along the beach in Edmonds. There had been a storm the day before and I guessed that either the wind or a train had killed the swan. I was interested in anatomy and skeletons back then and got started with dissections in school, an earthworm in grade school, a frog in junior high, and a roadkill gray squirrel on a summer break. I’d brought a roadkill raccoon home and skinned it to make a coonskin cap, with tail, like the one worn by Davey Crocket, or at least by Fess Parker, who played him on TV. I dissected the swan and pinned the wings on the south-facing back wall of the house to dry. I saved the swan’s down to stuff a pillow and used a section of a humerus for a sail-needle case. I was fascinated by the trachea. There is the long section in the swan’s neck, but there is even more in the sternum in a loop that runs from manubrium to xiphoid (if the swan’s sternum had those parts, but it didn’t) and back up and making an additional smaller loop before reaching the split into the bronchia at the lungs. If not for my growing interest in boating back then, who knows, I could have been a coroner.

Right, those twists and turns of life pushing us to where we want to be…..building boats for fun and personal satisfaction. ;o)

Thanks so much for sharing your story. Reflections of a journey well lived.

Who other than Chris Cunningham can move us from place to place with a positive message? So glad to receive that call back in August of 1977 reporting that Jim was on the bus for home and that you would be heading in the “write” direction too.

Chris,

Excellent article. I envy you!

You mentioned the boat (which is beautiful) as a “Marblehead.”

Is that the same as the Chamberlain?

Chip

Yes, the Marblehead dory skiff and the Chamberlain dory skiff are one and the same. William Henry Chamberlain had a boatshop in Marblehead, Massachusetts, and was active in the early 1900s. I also built a Chamberlain’s gunning dory for my father. He was born and was raised in Lowell, MA, and summered in Marblehead. When I was growing up, we went to Marblehead every other summer. So we both were drawn to Marblehead boats.

Great story and great insight on the path one takes through life. Few of us have any idea of where we’ll end up. Hopefully always a fun surprise.

As an avid reader of Sea Kayaker for many years and now Small Boats Magazine, I have always hoped that you could find the energy and resources to produce an on-line archive of all of the issues that Sea Kayaker published. I have paper copies of a number of issues which I reread, but I wish that the entire series was available to read on line or purchase.

Like Larry Cheek, I subscribed to Sea Kayaker in the 1990s and soon it became my favorite magazine, largely because it was so well written and edited (plus it was devoted to my favorite pastime). When it ended, I worried what would happen to its guiding light, Chris Cunningham. Years later I decided to build myself a wooden kayak at a WoodenBoat School class taught by Eric Schade, which led to wanting to build a wooden sailboat, which led to Small Boats Magazine. Lo and behold: I rediscovered Chris, still writing great reviews and personal experiences and editing what now is my favorite magazine. The guy is legendary!

This article is like many that make me anxious for the next issue or an old issue with an unread article from the past. Thank you again.

I am wrestling with the making of a tent/sun shade for my 16′ sailing yacht down here in the wet Bay of Islands, New Zealand. There are hours/days when I throw the template cloth on the floor and think “Stuff it! Pay the money and get a sailmaker to make it”…BUT…there, somewhere burnt into my brain forever, written by you, is the Chris Cunningham family mantra: “Why buy it when you can make it?” I will soldier on. The power of words, eh?

All the best and thanks for a great magazine.

Pete Jones

P.S. I’m really enjoying the voyage of the LUNA. It’s up there with The Unlikely Voyage of Jack De Crow.

Really? As good as Jack de Crow? That is serious praise!

Reading The Unlikely Voyage of Jack de Crow carried my dreams and humour whilst rebuilding our Wharram Hinemoa, MYSTERY.

I have yet to find a more connected story, thank you for the recommendation

Fantastic article for one that lives vicariously enjoying the articles about camp cruising our waterways. I have owned many powered sailboats, gradually downsizing to kayaks for their ease of maintenance and now age and balance issues have me thinking about camp/cruising in a row/sailboat. I would enjoy reading more about suitable designs with an emphasis on ways to make cruising the coast of Maine comfortably and safely.

Wonderful piece, and beautiful analogy about rowing and looking back at your path. Thanks.

Great article.