The French term voile-aviron translates to “sail and oar,” and describes a type of small cruising boats with a devoted following. French naval architect François Vivier has created an extensive portfolio of voile-aviron boats, and the Ilur is his most popular—many hundreds of them sail in France and a growing number are being built in North America. With a quiet, robust beauty, the Ilur’s current iteration represents an impressive marriage of classic form, 21st-century computer-assisted design, and modern plywood-and-epoxy glued lapstrake construction.

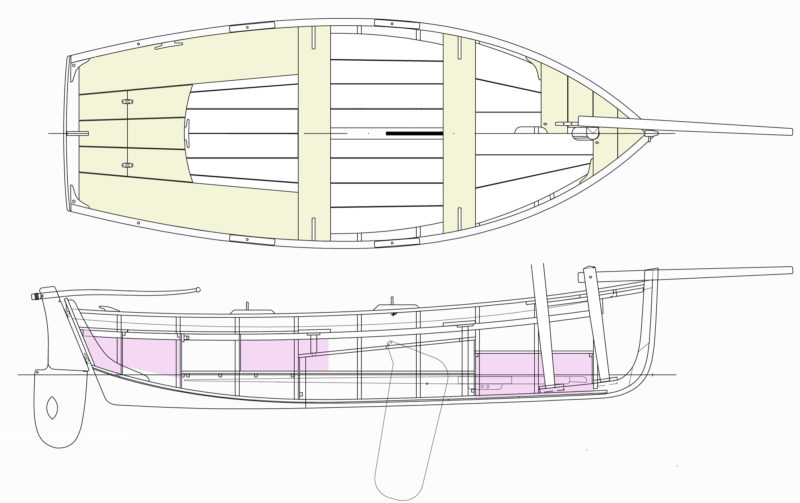

The Ilur arrives on pallets as a precut kit with CNC-cut components, including a strongback on which the hull is built. One of the key aspects of the kit-built method is the use of sawn bulkheads and interlocking longitudinal stringers that, as Vivier brilliantly executes, form both the building jig and the majority of the internal furnishings, so that after the hull is planked and flipped, much of the interior has already been completed. The result is an extremely strong hull that can be accurately and quickly executed by professionals and amateurs. The bulkheads and frames are 3/4″ marine ply, the planks are 3/8″.

John Hartmann

John HartmannThere are two rowing stations on the Ilur. The author made the aft station’s thwart removable to open up the cockpit for sleeping aboard, and he now usually sails without it.

With 10 strakes per side, there are a lot of rolling bevels to cut at the laps, and gains at bow and stern, but the work is pleasant, and not difficult. The builder will need to source lumber for the keel and keelson, floorboards, benches, thwarts, and spars. The plans are extremely detailed, and Vivier is quick to respond personally to emailed questions. Instructions are included for construction of rowing and sculling oars, and for hollow, four-sided spars. Vivier suggests about 400 hours to assemble the CNC kit; I took me almost twice that long, but the extra time went into items not covered in the plans, such as constructing hollow bird’s-mouth spars and casting a bronze mast partner.

The finished boat looks like a classic, traditional lapstrake boat. It also has ample storage with room below the cockpit sole for two pairs of 9-1/2′ oars, an anchor locker ahead of the forward thwart, and a large lazarette at the stern. For a boat less than 15′ long, it feels like a much larger boat. The hull shape is quite full, and the bilges are firm. As a result, the Ilur is very stable—I can stand or sit on the gunwale, and there are still three strakes of freeboard above the water.

John Hartmann

John HartmannThe mizzen and boomkin are set to port to keep clear of the tiller. This boomkin is hollow, allowing the mizzen sheet to run through it. The arrangement helps keep the stern a little less busy and prevents the sheet from fouling on the tip of the boomkin when coming about.

Under sail, the firm bilges show their worth in a wide range of conditions. As the breeze freshens, the boat will heel until the turn of the bilge buries, and the boat stiffens up and accelerates under its ample press of sail. In ghosting conditions, I sit to leeward, and the boat offers a sweet spot with minimal wetted surface area, while the full, curvaceous midsection of the hull maximizes waterline length for potential speed.

Though the Ilur’s measured waterline length is just over 13′, it is sneakily fast, and will happily sail in company with much longer boats such as Oughtred double-enders or Sea Pearls without struggling to keep up. In all conditions, the boat communicates clearly, gently, and progressively—there is simply nothing twitchy about her. Vivier designed the boat with built-in flotation in compliance with EU regulations, and it can be righted singlehandedly in self-rescue situations. Once upright, the water level inside the boat is below the top of the centerboard case, further improving the odds of a complete recovery.

John Hartmann

John HartmannThis Ilur carries the boomless Misainier rig. The lugsail, reefed here, has an area of 131 sq ft.

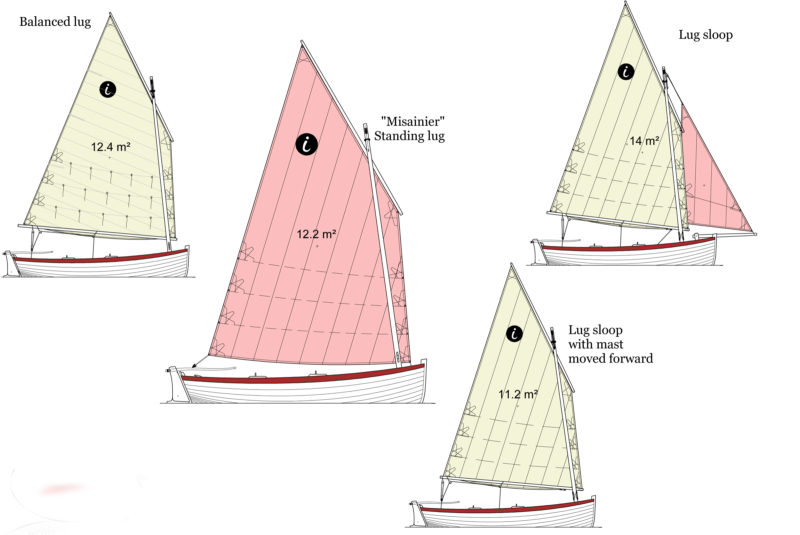

There are four rigs available, including a large, boomless standing lug, a balanced lug, a lug sloop, and most recently, a lug yawl, the rig that I had asked Vivier to create for the Ilur I built. The boat is well balanced under sail in all those configurations, and the weather helm is mild. It is surprisingly close-winded, and tacks through 90 degrees.

The full forward sections and generous freeboard provide a pretty dry interior when conditions are choppy, and any spray coming aboard drains to the bilges, so the crew is high and dry on the cockpit sole. In light wind, my favorite place to sit is on the sole, with my feet up on the leeward bench. My weight is low, the sail is well overhead, and the view over the gunwale is unobstructed. It is a delightful and cozy place. Likewise for the crew, a seat on the sole allows the gentle curve of the hull to form a very comfortable backrest, and the boat is roomy and secure.

The helm takes just a finger on the tiller, and often, using the mizzen to balance the helm, the Ilur can be trimmed to self-steer. As the winds strengthen, I sit up on the bench. Hiking out is rarely required. By the time whitecaps are widespread and the winds are in the 12–15 mph range, it is time to tuck in a reef. With the yawl rig, this couldn’t be simpler: turn the boat head to wind, sheet the mizzen in tight, and drop the tiller. The boat stays calmly hove-to, with the mainsail quietly at rest over the centerline of the boat. I walk forward and lower the sail while the boat tends itself. I move the tack downhaul up to the first reefpoint on the luff, then I move to the clew end of the sail. The mainsheet is reattached at the new reefpoint, and the sail is rolled into a neat bunt as I tie in the reef nettles while working my way forward. Back at the bow, I raise the main, then move aft to retighten the tack downhaul. After I release the mizzen sheet I can fall off onto my new heading. The whole process takes two or three minutes, and can be handled solo without any drama, even when conditions are boisterous.

The Ilur has stations for two rowers, but the glued-lap construction makes the boat light and easy to propel rowing solo in calm conditions. Even when the boat is loaded with a week’s food and dunnage, I can maintain 2-1/2 to 3 mph at an all-day pace. I drop the spars to reduce windage. The sail, yard, and mizzen fit inside the boat; the mainmast is taller than the boat is long, and is stowed with several feet overhanging the transom. The plans describe arrangements for fitting a small outboard to one side of the rudder. A long shaft is preferable, so no transom cut out is needed, just protection on both inner and outer faces of the transom for protection from the outboard’s clamps. I have not felt the urge to equip my Ilur for power, given how easily it is driven by sail or “ash breeze.”

Gabrielle Hartmann

Gabrielle HartmannThe lug yawl rig carries 134 sq ft of sail. The sprit boom on the main was suggested by the sailmaker, Stuart Hopkins of Dabbler Sails. With its forward end set high it is self-vanging, a useful attribute when running downwind.

Ilur owners who cruise with their boats can sleep aboard under the shelter of a boom tent. The CNC kit boat’s full-width sawn frames are rigid enough without being braced by a thwart, so the rear thwart can be fitted to lift out of the way, creating a tremendous open area for spreading out bedrolls. Here again, keeping the weight low in the boat pays benefits. The Ilur, like many boats designed for oar and sail, is designed with a relatively narrow waterline beam to improve its rowing qualities, and if the sleeping platform were at thwart height, the boat would feels “tiddly.” With the floorboards at the waterline, the Ilur is anything but tiddly with the crew sleeping there, and a restful night’s sleep awaits.

On a recent overnight outing on Lake Champlain, I anchored in a protected bay after a fine day of sailing. I watched an osprey catch its dinner a few yards from my anchored Ilur, and as evening fell, I was surrounded by a flock of several hundred Canada geese that shared my mooring area for the night. In the morning, as I was readying the boat and storing gear, and was investigated by a family of four otters that swam up to check me out at close quarters. Experiences like these are what I love about voile-aviron boats—they get you to beautiful places slowly and quietly enough that you join the neighborhood of wildlife without scaring it off. The Ilur is perfect for the task—capable, commodious, and comfortable.![]()

John Hartmann lives in central Vermont. He built his Ilur, WAXWING, to sail the 1000 Islands region of the St. Lawrence River, Lake Champlain, and along the coast of Maine. You can see his Ilur flying a mizzen staysail in “Mizzen Staysails Add Power” in our August 2017 issue.

Ilur Particulars

[table]

Length/14′8″

Waterline length/13′5″

Beam/5′ 7″

Draft, board up/ 10″

Draft, board down/3′

Displacement/930 lbs

Sail area/129 to 151 sq ft, depending on rig

[/table]

Plans for Ilur are available from François Vivier; kits in North America are available from Chase Small Craft or Hewes & Co. Marine Division.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Interesting boat. Why is displacement for a 15′ plywood boat 930 pounds?

You may be taking the displacement to be the boat’s weight. We usually use “Displacement” to refer to the weight/displacement of the bare boat plus the load recommended by the designer, and “Weight” to refer to the boat alone, without cargo or passengers.

Here are the weights for the Ilur as calculated by Vivier:

Clinker built, without rig: 540 lbs

Clinker built, ready to sail: 661 lbs

Strip built, without rig: 639 lbs

Strip built, ready to sail: 761 lbs

Christopher Cunningham, Editor

If John understands displacement and is wondering why it is so high for a 15′ boat, the ILUR has a lot of displacement because the hull was drawn with a lot of volume under the designed waterline. That may seem obvious, but that is why. The boat itself is not light, about 550lbs. That is what they call in the EU the ISO lightweight and it includes hull, anchoring/mooring equipment, rig, and oars. Still, reviewer John Hartmann carries at least 50 lbs of lead shot under the floorboards. He did a great job; his was the first kit-built ILUR to hit the water in the US. When I started into kits, I was lucky to become a partner with Vivier and be the first to bring his boats to the US market. I am excited to continue doing so with complete kits.

Something doesn’t seem right. If the hull+rig = 640 lbs and the total displacement is only 930 lbs, then she can only carry 290 lbs of people and gear?

According to French regulations the Ilur can carry 5 people. Roger Barnes explains how he bought his boat in France from a man whose family increased by one and since there were now six of them he needed a bigger boat. See his YouTube video.

Beautiful boat, very capable, practical, robust, and easy to sail. Preferred craft of Roger Barnes of the Dinghy Cruising Association. There is a story about his Ilur, AVEL DRO, in the August 2018 Messing About in Boats. She is also heavily referenced in his 2014 book The Dinghy Cruising Companion: Tales and Advice from Sailing a Small Open Boat.

Boat Smart!

Kent

As the owner of the blue Ilur in the photo above, I concur that she likes a little ballast if there is enough wind to require a reef (maybe 10kts). Fifty pounds makes a noticeable difference, and settles her down. If you don’t need a reef, you don’t strictly need ballast, but I always carry 50 lbs.

I’ve sailed my Ilur, solo, in a late September breeze in Boston’s outer harbor. I had 100 lbs of ballast, in 4 lead sleds in the bilge. By mid afternoon, I had all three reefs in her, more because of the size of the waves than the strength of the wind. I found her easy and comfortable to handle, but more work to row. While reefing, she lay to quietly with very little leeway.

As for overall weight, I think the Ilur is a heavier boat than other glued ply designs. She’s probably comparable to a fiberglass boat her size, such as an O’Day Osprey. Under way she feels closer to a small keel boat, such as a Herreshoff Bullseye, than a typical lightweight centerboarder.

Other nice things about the Ilur:

1. She’s pretty dry going upwind. The high sides block a lot of the spray.

2. You can stand up in her and walk around, just like you can in a Cape Cod Catboat. She won’t dump you.

3. She’s buoyant up forward. This is the secret to much of her nice handling I think. A boat with a lean sharp pointed bow will go closer to the wind, but can also trip and broach when pushed hard downwind. The Ilur will roll pleasantly along in big seas. One time my wife was in the bow, unsure of how to handle a mooring pennant, and I went forward to help her, and we were both right up in the bow of a 15′ boat. I think most boats would toss us if we tried that.

4. Simplicity. This was the goal for my Ilur. I wanted a sailboat as simple as a kayak. She’s actually not as simple as a kayak, but she’s pretty close. The ‘misainer’ rig has one mast, one halyard, one sheet, and no boom to bonk my crew on the head. Simplicity gives peace of mind.

Peter, next month I will receive delivery of Ron Mueller’s kelly-green Ilur. I am looking forward to all you wrote above. Delmarva, the Chesapeake (home fields), Kerr Lake (North Carolina) and, hopefully, Maine will be some of my retirement multi-day trips, in a few years. Hoping to meet all Ilur owners. Love the colors of yours.

Rob K.

I understand displacement, but it actually seems low to me, given the weight of the boat. The weight numbers are a little confusing because Vivier’s site shows both sets of figures—the 540# ISO weight, as Clint mentions, plus the four different weights referenced by Chris, which suggest the ISO weight for the glued lapstrake version is really 660#. I’m assuming Clint is right, since he’s weighing the kits going out the door. But here’s my question in considering this boat for a winter project—is there really only a 300-350# payload after adding some ballast? Is the total displacement also an ISO number with some big water safety factor built in? Four hundred pounds, less ballast, doesn’t seem like much—either for the overall size/weight of the boat or for the intended use—but it’s hard to find comparable figures for similar boats so I may be off base. Thanks for your thoughts.

Beautiful boat! I noticed that the mizzen mast is set slightly to port of the centerline in order to make room for the tiller. Does this have any negative impact on the boat’s sailing performance?

Can’t speak from personal experience, but Phil Bolger freely used off-center mizzens, and sometimes mainsails as well, and insisted there was no performance penalty.

Having built an Ilur with the lug/sloop configuration and having three Ilur seasons under my belt, I have not doubt that four people aboard an Ilur would not be too much. In fact, I recall John Hartmann sailing (at the Small Reach Regatta in Maine) just fine in light air with three others aboard. The lug/sloop configuration has 151 sq ft of canvas in the air. That is A LOT of sail and is awesome in light air. At 12-15 knots I’m ready to tuck in a reef and if sailing solo am happy just about then with 50 lbs of lead shot in the bilge. Having admired both of these other Ilurs in person and in action on the water, all I can say is there is not a bad choice. Whatever strikes your fancy! Here is a link to CLARISA (my Ilur) sailing on the Tangiers Sound (Chesapeake Bay). Roger Barnes was a major inspiration and John Hartmann was a guiding light and great help in getting my Ilur launched. What a great design!

I’m local. When you’re ready to sell I’ll be there with a brick of cash! 😉

That is a beautiful boat. What material did you use for your sails? Oceanus or Clipper Canvas?

Vivier has certainly managed to put a lot of boat under a 15′ hull. Beautiful, rugged appearance and buoyant fore and aft sections. I too wonder where does Ilur gain its weight. Similar design and size boats can be half the weight, for example Oughtred’s Tammie Norrie.

John,

I’m building an Ilur. I was thinking of removing the side panels and the bulkhead under the side benches to facilitate sleeping. Is this necessary?

You removed the thwart, is there enough room between bulkhead and centre oars case without my proposed modification?

Andy,

Vivier has addressed this with update in “kit” design.

https://www.vivierboats.com/en/clinker-kit-ilur-better-sleeping-onboard/

I think with that change you can sleep with comfort and keep flotation chambers as in the plans.

I’m starting building mine and intend to stick to the design – with the exception of removable thwart.

Lukasz,

I’ve now flipped my hull and will design the thwarts to be removable like WAXWING’s (an Ilur in Vermont blog). There’s plenty of sleeping room room with one’s head towards the bow and feet at the tiller.

I had thought about waterproof hatches to capitalize on using the space under bench and forward flotation chambers, this seemed a bit complicated and unreliable though.

So my plan B is to make the floorboards and benches hinged to give access to the voids beneath – I intend to fill the buoyancy chambers with dinghy flotation air bags so I can deflate them to make room for luggage, ‘Roger Barnes’ style, when on expedition.

Yesterday, I fitted my wine-cellar racks beneath the floor boards alongside the centerboard case. Why use lead ballast when there’s fine Merlot and even Chablis on ice to be had (red bottle to port, green bottles to starboard)?

Forward of the centerboard case there is a gap between the side buoyancy compartments that is about the right size for a galley box and a battery box.

Insulating the buoyancy compartments either side provides space for expedition comestibles in an insulated cool box with ice. As the food goes down, simply blow up the dinghy bags to replace it.