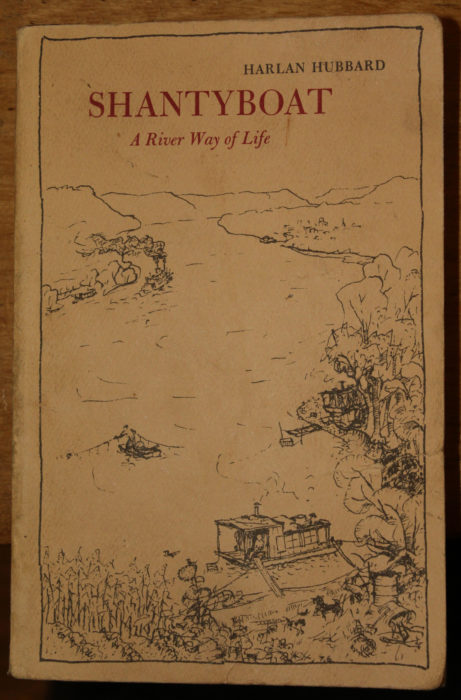

When I was planning for my rowing trip down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers in the early 1980s, I read as many books as I could find on traveling those waterways in small boats. Four Months in a Sneak Box by Nathaniel Bishop was my main guide, as it was his trip that I was going to duplicate. I also read Mississippi Solo by Eddy Harris and Old Glory by Jonathan Raban, both good reads, but Shantyboat: A River Way of Life by Harlan Hubbard was my favorite and most inspiring.

In 1944 Harlan and his wife Anna built a shantyboat near Brent, a cluster of houses along a road paralleling the Ohio River just upstream from Cincinnati, Ohio. They stayed there on the banks of the river for two years, living on what they could grow in their garden or catch in the river, and left Brent on the high waters of November 1946. They stopped for the summer in Payne Hollow, about 120 miles downstream, and stayed there for the summer of 1947 before moving on. They reached New Orleans in 1950 and stayed another year in the Louisiana bayous before returning by car to Payne Hollow in 1952. They settled there, building a house and a life for themselves.

Harlan’s account of the river journey did much more than help prepare me with the details of what I might encounter on my rowing trip; it described an independent and idyllic life:

“The season for syrup making did not last long. We continued our sugar camp for nine days, boiling down washboilerfuls of sap. It was a joy to be working in the winter woods, above the river, building huge fires. I would roll some logs and big chunks of hardwood on the last trip before bed time. Then I walked back to the boat through the dark, starry woods by a path well known. Our dinner was often shad broiled over the coals and potatoes and corn dodgers baked in the ashes. The new syrup was delicious with the hot bread.”

The book played a significant part in my decision to live in a number of cabins in the woods, usually without power, plumbing, or phone.

When I was on my way rowing down the Ohio in the winter of 1985, I stopped in Brent. From my journal:

It turned cold last night, about 25 degrees at my camp in an open shanty at Shady Grove. I slept with my clothes on and managed to sleep well enough. Getting up this morning, though, was painful. My whole body ached with cold, my hands stung. The river had dropped about three feet overnight so I had to drag my boat down the bank to the water of Nine Mile Creek.

I was on the water by 7:30 rowing hard to warm up. As the sun was coming up behind a bank of high clouds to the east there was clear sky overhead and a thin vapor on the water. Vortices in the breeze spun columns of mist ten feet in the air and carried them across the river, undulating like a tall wobbling stack of dishes. Six miles into the morning the sun breached the clouds. I ferried across to the Kentucky side to Pleasant Run. Somewhere on this bank, now all covered with trees, Harlan Hubbard built his shantyboat.

Though it was still pretty early, I put ashore at a ramp leading through a tunnel under the railroad tracks. There were two old houses there in what must be the town of Brent. No one was up at the first house I knocked at. There was a light on at the second. I rang the bell and knocked. An old lady came to the door. Age was what I was looking for, since the Hubbards were there 20 or 30 years ago. The woman remembered him but didn’t know him. She said that there had been an article about him and his paintings in the Cincinnati newspaper last week. She said the Hubbards are down at some place, some hollow, and that they raise a lot of their food down there.

I got about all I could from the woman, a Willis, one of the families that Hubbard mentioned in his book. As I was walking back to the boat I remembered that it was Payne Hollow where the Hubbards spent a season on their drift downriver. I looked through my charts and found two hollows where they might be. I was 105 miles from them. I got quite excited. The Hubbards were still alive, still living on the river, and two days away. I am full of excitement that I might get to meet the Hubbards.

Tearing up the bottom of my sneakbox approaching Payne Hollow turned out to be a stroke of good fortune.

When I reached Payne Hollow I rowed ashore and ran into a sharp rock hiding just below the surface of the muddy river water. I pulled the sneakbox alongside the Hubbard’s aluminum johnboat and took a look at the damage. The rock had carved a deep gouge in the bottom of my boat and I’d have to dry it out and make a repair before moving on. I walked up into the hollow where the Hubbard’s home sat high on the left bank. I found Harlan and Anna there and introduced myself. I said that I had just come to meet them and then be on my way, but I’d damaged my boat and asked if I could stay while I made a repair. I would have been quite happy setting up camp by the river, but they insisted I spend the night in their home.

The Hubbards’s home bathed in the evening light as the sun sets over the Ohio River. Harlan’s studio is to the right.

Harlan was 85, quite lean and square shouldered. Anna was 83 and wore her long silver hair pinned up. Both of them were soft-spoken and had a very serene air about them; they were somewhat formal, especially Anna, though warm and welcoming.

I returned to the river, emptied my gear into the johnboat, and propped the sneakbox up on edge to let the sun dry the gash in the cedar hull. Harlan had another visitor that day, a man who worked at a museum or an art gallery, and I tagged along as Harlan walked us to his studio a few yards from the house to show the man his latest work. I had always admired the woodcuts and the pen-and-ink drawings that illustrated Shantyboat; Harlan had been doing paintings, mostly local landscapes in oils on Masonite boards. His studio doubled as his workshop and contained a fascinating collection of beautiful paintings and hand tools gleaming with a patina of long service.

I returned to my boat later that afternoon, cut away the torn fiberglass and wood fibers, and applied a ’glass-and-epoxy patch. There was just enough daylight left to cure the epoxy as the sun settled over the woods on the opposite side of the river.

Some of my memories have faded, but I think I sat down with the Hubbards to a dinner of homemade soup that evening. The table shared the living room with Anna’s grand piano. (Harlan’s instrument was a violin.) Their bed was stored out of the way to one side of the stone fireplace Harlan had made. When it was time to turn in I was given a bed on the uphill side of the house. On the walls around it, many of the household items Harlan had made were hung from pegs and nails. There was a popcorn popper made of screen and stout wire with a wooden handle. The room I was in was up a step but not separated by walls from the living room where Anna and Harlan would sleep. I could see Harlan’s side of the bed and the gleam of his smooth white hair was the last thing I saw before he extinguished the kerosene lantern. The last words I heard were from Anna: “You get some good rest, dear.”

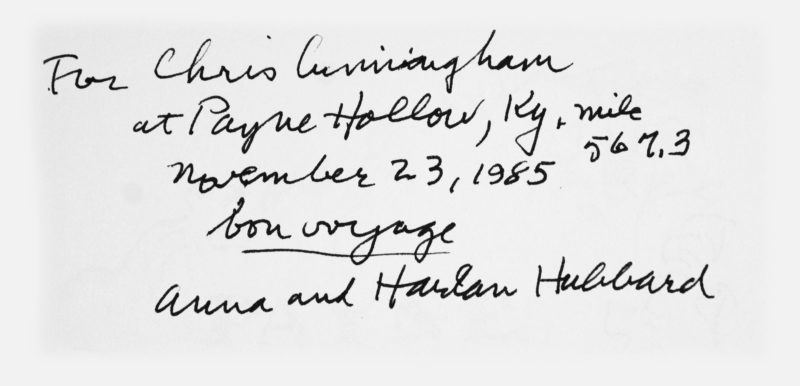

In the morning I repacked the boat, and returned to the house to say goodbye. Harlan gave me a copy of his book Payne Hollow: Life on the Fringe of Society, with the inscription:

I didn’t take any photographs of the Hubbards, just the photo of the house you see here. I couldn’t imagine asking them to pose for me or to take photos of them surreptitiously. A camera takes away the being in a place, the being with someone, and I didn’t want to give up a moment with them in Payne Hollow. My memories have, of course, faded over the past three decades, and it is likely even what remains with me will fade. The one thing that I won’t forget is the tenderness in their voices as they said goodnight to each other. It gave me a glimpse of what love becomes after a long, full life lived together.

I carried on down river to the Gulf of Mexico. Anna died the following spring; Harlan two years later.![]()

Thanks for sharing this memoir. I have enjoyed two of their books and I’m glad to know a little of their later years. And thanks for sharing this story in such a tender way.

This is a touching story; it’s remarkable that you were able to meet them. Inviting a stranger to stay the night in their home causes me to think that they must have been kind, generous people. There are still people like that today; this story is a reminder that the world is not all bad.

In all of my travels I’ve found people everywhere are quite accommodating. In 7,000 miles of coastal and river cruising I could count the inhospitable people on one hand and still have my thumb and index finger left over.

I think there is a special sense of community along waterways. It also helps to be traveling in a small boat, especially under human power. I knocked on the door of one home on the St. Marys river on Christmas Day, just to get water and was was invited in for Christmas dinner. An elderly woman living alone near the Intracoastal Waterway just south of Charleston South Carolina came to her front door after I knocked, took a look at me, then a look at my canoe and said, “Honey, ain’t never been a thief come by canoe. Come on in.”

Thanks for sharing the memory. Lovely story nicely told. And nice stewardship of available resources. Tell us more (or point to where you have already) about your Bishop/Sneakbox adventures.

I have Shantyboat, Shantyboat on the Bayous, and Payne Hollow, as well as the DVD Wonder. I treasure and have enjoyed them just as I did my wonderful illustrated copy of Swiss Family Robinson I once possessed as a boy. All were filled with tons of practical solutions, ingenious contrivances, and field expediencies that were thrilling to read—to say nothing of the exciting locations and fanciful encounters with both local creatures and local peoples. I’ve never traveled by oar, though I built a rowing skiff with my grandson for him and his friends on Puget Sound and I’ve fished most of the Sacramento and put my line into many other waters across the country and deeply love the live water found in rivers and streams. Thank you to Mr. Cunningham for reinvigorating the pleasure I’ve found hearing of the lives of the Hubbards.

Hi Chris. Another interesting read is On the Water: Discovering America in a Rowboat by Nathaniel Stone. He too reminisces about the Hubbard’s shantyboat trip down the Mississippi although to my knowledge he did not meet them as you did.

Nat started his trip in NYC in a single scull and between taking shortcuts and portages got to the Mississippi delta at New Orleans where he took a break. He returned in a more traditional rowboat to ply his way in the Gulf and then up the East Coast back to New York City. The change in craft was dictated by the need to be able to sleep aboard in the less hospitable parts of the country.

Not done, he left NYC and was determined to reach Eastport, which he did after being denied passage through the Cape Cod Canal. Undaunted he completed his goal by rowing around the Cape and reached his final destination.

So did they ever have to leave their house because of flooding? Not too worried about that here in DownEast Maine, though the lobster dock I manage should have been built a foot higher as it is almost under water on big tides now.

Many of the towns I stopped in along the Ohio River had markers to show the river level during the Great Flood of 1937 where the waters reached 79.9′ above flood stage. In his book, Harlan writes about a previous homestead in Payne Hollow: “House and barn were carried away by the 1937 flood.” So they knew about the Great Flood. Later he writes: “From the beginning we had determined it [the house] should be above flood level.” None of the neighbors could tell the Hubbards where the flood waters had reached, so Harlan and Anna used “a carpenter’s square, a piece of string with a weight on it and a tape line…to calculate approximately the elevation of the chosen site above the normal pool of the river. The Ohio is never expected to exceed this mark and we hope this is a true prediction, but for our part, flood water in the cellar would be a small price to pay for the sight of the river grown to enormous size, extending from our hill to those on the far side, covering the tallest of trees.”

Chris, thank you for your exceptional article! I don’t know how I missed this article in March. I grew up reading Shantyboat. It was one of the earliest books I can remember reading, and Payne Hollow is a classic in its own right from the ’70s. My grandparents’ home was right next door to Harlan’s brother, Frank, in New Rochelle, N.Y., so we heard regular stories of Harlan and Anna’s exploits when Frank and his family would come to dinner, though I never did have the pleasure of meeting Harlan or Anna themselves (I was a young boy at the time). Frank, Jr., was a well-known harpsichord maker, and wrote a classic book on the subject. They were a talented family! I seem to recall that Harlan and Anna had become something of guiding lights in the back-to-the-land movement of the late ’60s and early ’70s. You definitely have some memories to cherish. Thank you for sharing them.