I never saw Frank Prothero smile. He was a gruff, imposing figure with enormous beat-up hands who looked like he had strayed here from the 19th century. He was revered in Seattle’s wooden boat community for his lifelong career as a shipwright and, even beyond the respect due for his inestimable accomplishments, he had an air about him that commanded it. I used to see Frank back in the early 1980s when I was working for Joe Bucek and Land Washburn, owners of the Wooden Boat Shop in Seattle’s University District. I was in my late 20s and had built just a handful of boats and knew just enough about boatbuilding to mind the store.

Frank was then in his late 70s and had been building boats for over 50 years. It was in his blood. His ancestors in Wales had been building boats since the late 17th century, his great-grandfather immigrated to Seattle in 1870 and went into business building boats on the shores of Lake Union, and his grandfather, father, and brother were all shipwrights. Frank was in a retirement, of sorts, and was building himself a 65′ gaff-rigged topsail schooner in a floating boatshop on the south end of Lake Union. He had been working on it since 1965.

Frank would often come to the Wooden Boat Shop, always wearing a newsboy hat, a khaki shirt, and leather work boots with white crepe soles. I don’t recall ever speaking to him beyond a hello when he came in, or getting any more of a reply other than a nod. When he wandered the aisles looking at the wares, he had a habit of pressing his lips together tight in a straight line, turned neither up nor down at the corners of his mouth.

During one visit, he was browsing around the store while Joe was helping another customer come up with a fix for a leak between his boat’s keel and a garboard. Joe was well aware that Frank was within earshot, and when he had come to the end of his recommendation he turned to Frank and asked, “Does that sound about right, Frank?” I don’t recall that Frank even looked up, but he muttered, matter-of-factually, “I don’t give a good goddam what he does with his garboard.” I was thunderstruck; steeped as I was in Seattle politeness, I couldn’t imagine being that unbridled, and admired him all the more.

I could put Frank’s abrupt manner in a familiar context because my Massachusetts-born father had raised me on the Downeast humor of Marshall Dodge of Bert & I fame. His record albums were inhabited by lots of crusty New England old-timers. Dodge tells a story about Maine shipbuilder Harvey Gamage impressing the owner of a boat that needed a fix for a puzzling leak, at a garboard in fact. Gamage took one quick glance at the boat and gave him the simple solution to the problem. The customer asked, “How did you know just what to do?” and Gamage replied, “Goddammit man, I can’t understand all I know.” Frank was just such a character. Genius can be forgiven for the faults that often attend it.

Joe let me accompany him once on a visit to Frank’s shop. It sat on a 110′-long barge, and the schooner filled the cavernous shed built over it. I kept my eyes open and my mouth shut. As I recall, Joe told me that Frank started the project with the lofting—no model, no drawings, no offsets—he had all that in his head and just went straight to work with a batten. The hull was heavily timbered and immensely stout, and yet there were delicate carvings on the cabin cornerposts. The boat had already been 17 years abuilding and it was clear the Frank was not taking any shortcuts to finish the schooner in the years he had left in his life. Everything he did was a devotion to the best traditions of an era he had seen come to an end. He wasn’t just building a schooner, he was making a monument.

During the construction of the schooner, vandals had opened a faucet by Frank’s shop and left the water to pour into the barge. It went unnoticed for quite some time and eventually the barge listed heavily and the schooner fell over on its side. Frank pumped out the barge, righted the boat, and went right to work repairing the damage to the hull and resuming construction.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamFrom lofting to launching took Frank 21 years. Here, with one hand on the boat’s cradle and the other on his hip, he takes a last look at the hull’s underbody.

He launched his schooner on a sunny day in July 1986. After working on it for over two decades, getting it afloat on Lake Union could have been a time for Frank to be beaming, but all the while his face was set in that tight-lipped impassive expression. He christened the schooner GLORY OF THE SEAS.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe launch of the schooner was done without fanfare. I suspect Frank may have been eager to be done with it so he could get back to work.

Frank wasn’t being vain about his work in the name he had chosen. It honored a 250′ three-masted clipper ship, GLORY OF THE SEAS, designed by Donald McKay, best known for his GREAT REPUBLIC, the largest full-rigged ship ever built in America and FLYING CLOUD, a record-setting clipper. GLORY OF THE SEAS was launched in 1869. She was the last and the finest of McKay’s clipper ships and sailed for 41 years before being stripped of her masts to serve as a cannery and cold storage. On May 13, 1923, she was run aground south of Seattle, at Brace Point, and burned for her iron and copper. Frank, then 18 years old, was there and took part in the salvage. He must have seen how beautiful a ship she was and regretted taking part in her ignoble demise.

Frank died on November 16, 1996, at the age of 91. Just the night before, he had been working on GLORY. As far as I know, he had never raised sail on GLORY, but that wasn’t his goal. His son, Bill, related how Frank felt about sailboats: “He used to say the only reason to take them out was to have an excuse to work on them when you get back.”

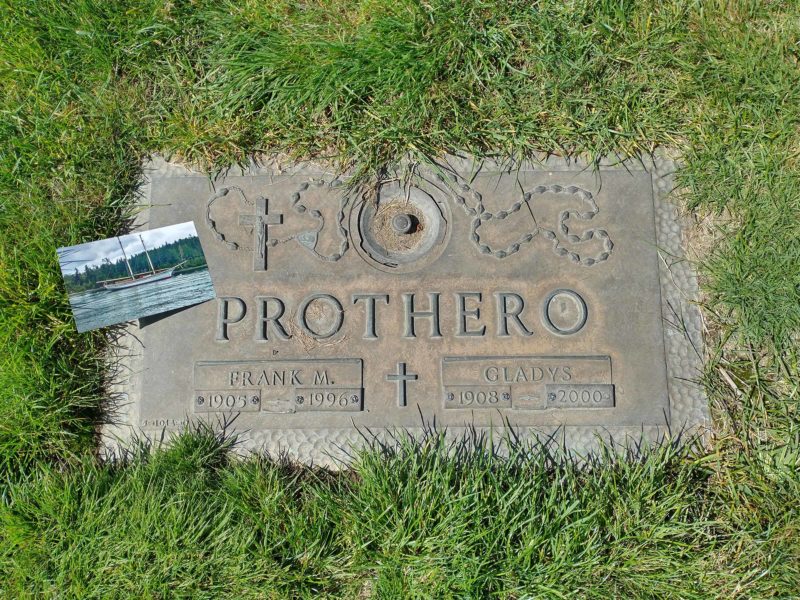

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamWhile I was looking into Frank’s background for this story, I happened upon the location of the grave where he and his wife were interred. The cemetery is along one of my regular bicycle routes and I’ve often ridden to it to pay a visit to the grave of my best friend’s mother. I had unknowingly passed by within a few yards of Frank’s grave many times.

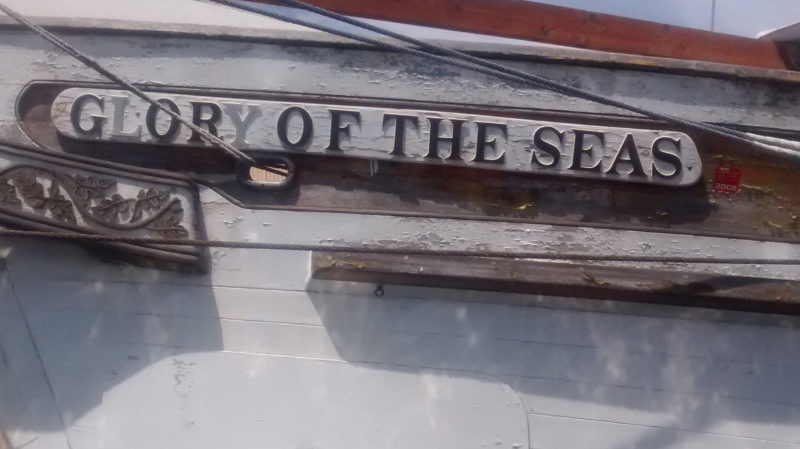

GLORY remained afloat in Lake Union and for years, I often visited her when I kayaked around the lake. She was tied alongside a boat shed that could have protected her but for her masts, towering even though her topmasts were gone, so she remained out in the weather. The covering built over the deck was eventually in tatters. Her topside paint peeled, and a tangle of running rigging hung from the mastheads like cobwebs. The nameboard on her port bow couldn’t have been Frank’s work. GLORY OF THE SEAS was spelled out in plastic letters tacked on an unadorned board with the first S in SEAS upside down. Her condition worsened year by year, and then last year she disappeared.

Jeremy Snapp

Jeremy SnappAfter Frank passed away, GLORY languished at the south end of Lake Union.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamI often visited GLORY when I went kayaking on Lake Union. She was hidden behind a row of floating boat sheds, out of sight, and seemingly forgotten.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe nameboard must have been a temporary one. It was hastily done and showed none of the care that Frank put into the trailboard (at left).

Several months ago, driving into Port Townsend, I caught a glimpse through the poplar trees along the road of a schooner propped up in a boatyard. It was GLORY. She had a gaping hole in the starboard side where the planks had been removed. Fragments of rotting frames had spilled out and littered the ground around her. A shipwright I spoke to there said that she was in need of a new owner, someone who had the skills and the finances to put her back to rights. A month ago, I went looking for her and she was gone again. A woman at the marina said she had been launched and was taken to Lopez Island.

Lark Dalton

Lark DaltonAnchored off Lopez Island in Washington’s San Juan archipelago and under the care of a skilled boatbuilder, GLORY is finally getting some of the attention she deserves.

I tracked GLORY down and she’s now in the care of shipwright Jeremy Snapp and his son Trevor. I met Jeremy when I was living on Lopez Island in the early ’80s and was impressed with the caliber of his work. GLORY is in good hands, but she’ll need the support of a broad community to fund her restoration.

Lark Dalton

Lark DaltonFrank had a hand in building hundreds of boats and GLORY OF THE SEAS, the last of them, is perhaps his finest.

Jeremy sent me the photograph above of GLORY at anchor just off the shore near his home and to see her looking shipshape again, freed from the confines of Lake Union, nearly brought me to tears. However gruff Frank might have seemed to me, this great beauty was always in his heart.![]()

If you’d like to support Frank Prothero’s legacy and the restoration of GLORY OF THE SEAS, check the website in her name and contact the Snapps at [email protected].

I was living on a houseboat just north of Prothero’s shop back then and went down to see her when she came out of the shed. I can’t recall now if it was for the actual launching or not, but boy, was she impressive. Her relatively rapid decline seemed so unfathomable to me; such a precious thing being let go. I also stumbled across her while in Port Townsend and her condition pretty much caused me to lose all hope. I can’t tell you how good it is to see her coming back; the effort to get her to the point of relaunching alone must have been huge.

I always admired Frank’s philosophy, that the only reason to take out a boat, was to bring it back and work on it. ;o)

Great news that it is being restored!

This is good news, more power to Jeremy. It was devastating to see GLORY hauled out in Port Townsend with mulch spilling out of her guts.

I also have memories of visiting Frank and GLORY in the shed. This was prior to boat school and much of any carpentry experience on my part. But I had a long wandering eye and intense interest in boats. GLORY so dominated that space, the shed was like a cathedral. It was SO much to absorb. I visited a few times. Somehow Frank tolerated me. Sometimes he would be sitting in his moaning chair back in a nook of the shop. I have not the foggiest memory of what either of us said. Surely not much. I was vaguely terrified. What could I say. But it was OK.

There’s something profoundly sad about a person who goes through a long life life without smiling.

As a person of advanced age (69) who interrupted a career as a merchant mariner to do a seven-year stint as a wooden boatbuilder back in the eighties, and have continued to build, and work on wooden boats since, I’ve read a lot about Frank Prothero, and have admired him from afar.

For me, part of the the joy of wooden boats is the camaraderie involved. Early in my apprenticeship, there were many folks with much more experience, that willingly, and happily, shared their knowledge with this then-neophyte. For the life of me, I don’t get why Mr Prothero’s rude response to a reasonable inquiry actually increased the editor’s admiration of him. Mr Prothero’s brain was clearly that of a master shipwright, but his heart was that of a jerk!

Frank wasn’t malicious, a defining trait, I think, for a jerk. As I was considering writing about Frank, I talked to a few people, all boatbuilders, who had met him and had similar stories to tell of him as a gruff character, but none thought any less of him for his rough edges. He was regarded with the utmost respect.

Well, I don’t know about that. If the recipient of a rude rebuff feels it as malice, then the effect of it is indeed malicious—intended or not. Like David Mitchell above, I’ve enjoyed a great deal of kind advice and assistance from professional and amateur boatbuilders alike as I’ve advanced in my avocational career. Nobody ever hammered me for a dumb question. One person drove 90 miles to my home—twice—to provide hands-on help with construction problems that were a little beyond my competence. Another generously loaned me his homemade spar lathe. Still another contributed a bucket of lead shot for ballast. I think these are the people who deserve our utmost respect.

That’s a beautifully written profile, Chris. I never met Frank Prothero, but I’ve heard a lot about him and have been deeply curious as to what he was like on the personal level. I now feel like I have a complete and full-color picture. And it was probably better to read about him at this distance than to have been introduced!

I was afraid the story was going to have a thoroughly unhappy ending as far as GLORY is concerned, but it’s great to learn that she’s now in the care of a capable owner. Schooners are the most beautiful of all sailing craft, and this is a fine example.

Nicely written and a well chosen story, Chris. You don’t hear enough about Frank Prothero and his life building boats in the Northwest. Maybe his gruff approach to life keeps his story hidden. I too worked at the Wooden Boat Shop, but around 1993, after the Land Washburn era. Frank was still coming into the shop then. He would drive up in some unmemorable monstrous sedan that was always spewing steam from the radiator. After a few visits to the store, I made a mistake saying, “…hey Frank your car is overheating.” His response was a penetrating scowl. He didn’t need words. “Yeah, I figured you noticed,” was my response. I tried to laugh my way around Frank’s hardness knowing he was a giant in the world of boat building.

I was hoping some great foundation would recognize and save GLORY and make her Seattle’s icon to its maritime history (big ask for such a venture). Happy to see her in good hands. I hope GLORY has a same future of care and love as the ALCYONE, a 65′ schooner Frank built in his backyard.

I never had the pleasure of meeting him, but a friend once told me of having the chance to meet Bud McIntosh. He, too, was a master at his craft but, unlike Mr. Prothero, it seems that everyone who met him was touched by his warmth, his willingness to share advice, tools, and most importantly, encouragement. This was certainly my friend’s experience. I’m 70 now, and I still don’t understand the whole “crusty old guy” act, even when I can view it (now) from an old guy’s perspective.

J. Daw

Uncle Frank always treated my Dad and his brother like the black sheep. Regardless we admired his skill. After all, he put to sea and rode out the Columbus Day Storm on one of his boats. Seeing this neglect saddens me deeply!

Harry Prothero

Can anyone comment on the status now?