Corky Gallo

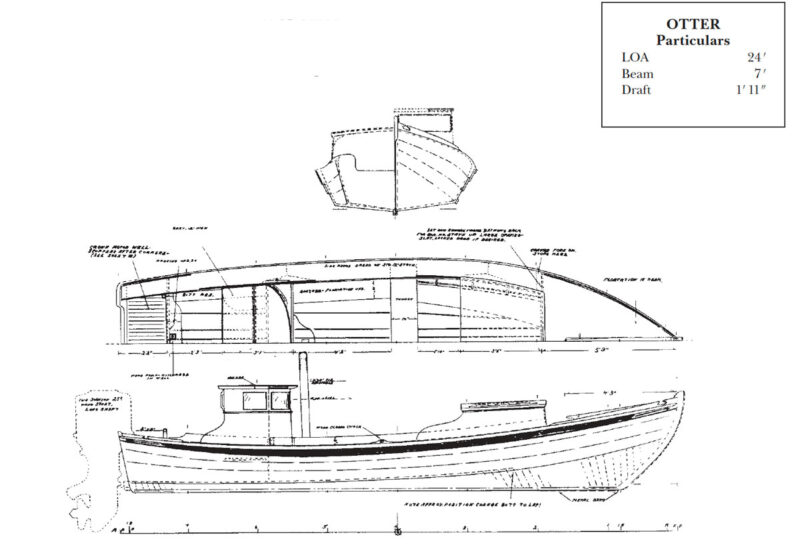

Corky GalloCapt. R.D. “Pete” Culler designed this 24′ outboard-powered launch in lengths ranging from 15′ to 30′; Bill Perkins adapted the construction and cabin design for his particular purposes, and built this example.

Bill Perkins is a tall, soft-spoken man with an easy Southern grace. The man knows boats, so when he needed one to transport supplies and people from the Atlantic coast of Georgia to his old family house on Cumberland Island, he looked around pretty hard before settling on Pete Culler’s 24′ Fast Outboard Launch. Capt. Culler designed a whole series of these boats, ranging from 16′ to 30′, all with that signature Culler sheer and stem, and all based upon the design and construction practices of the old Chesapeake Bay working skiffs.

The boats of this series were drawn, as their name implies, with outboard power in mind. This is an important distinction: For long-term reliability and economy, I prefer an inboard diesel on a boat this size, but if your particular situation calls for convenience, shallow draft, and a better power-to-weight ratio than an inboard diesel affords, it is hard to beat a modern four-stroke outboard. Boats must be designed for where the weight will be concentrated, though, and to simply slap a big, heavy outboard motor on the stern of a boat intended to carry an inboard engine amidships is bad form. Considering that this series of boats has such a traditional pedigree, being designed from the outset for outboards makes these launches distinctive.

Culler’s plans call for conventional plank-on-frame Chesapeake construction: caulked herringbone bottom planking, and massive backbone pieces and transom. But Bill’s needs dictated that he come up with something different: OTTER is stored in a shed, and her hull is supported by just two rails—though, with the boat’s 425-lb motor hanging from the stern, Bill requested a ground-floor berth “so I could support the transom with blocks.” The boat is transported by forklift from the shed to water, and this requires additional strength. “I made a conversion,” said Bill, “to glued-up construction that has proven itself over the past few years in rough water and rough handling ashore.”

Bill began construction by setting up the molds on 3′ centers, and then placed topside frames at 18″ on center. Structural plywood bulkheads, thick floor timbers, and a robust keel help hold the shape.

The bottom is composed of a 1″ × 4″ Western red cedar herringbone-pattern inner layer, and 1⁄2″ fir plywood — laid as diagonal plank opposite to the first layer — on the outside. Bill reports that, working forward from the stern in this high-chined hull, the twist required in the cross planking becomes unworkable in about the forward third of the boat as the chine curves up. From there the planks are gotten out of thicker stock, with the required twist planed in before bringing them down to the correct thickness (an electric plane is a key tool)—a process covered in Howard Chapelle’s Boatbuilding and in various writings of Pete Culler. “The amount of shape this technique produces in the bow is surprising,” says Bill. “I think aspiring builders might like to know about this alternative to sheet ply.”

Starting from the stern, the second bottom layer was laid down in epoxy on an opposing diagonal to the raked herringbone first layer, so the after two-thirds of the bottom is double-diagonal construction until the required twist in the planking again becomes too much. The remaining forward portion was then cold-molded in two 1⁄4″ layers, the laminates glued and stapled to the faired first layer. The finished interior shows the traditional herringbone planking. The cedar bottom is sheathed in two layers of Xynol on the outside and one layer of 6-oz ’glass on the inside so the inner face of the planking may be finished bright. “I watch carefully for deflection or damage of the planking,” says Bill of the boat’s rugged treatment and equally rugged construction, “but can see no problem. The boat has never made a sound when being handled by the forklift.”

Corky Gallo

Corky GalloOTTER, Bill Perkins’s Culler launch, displays her nimble handling (left). Perkins beefed up OTTER’s hull construction to accommodate the rigors of dry-stack storage and forklift transport (right).

OTTER’s topsides are of 5⁄8″ glued-lap okoume plywood—an effort to keep weight low in the boat. No lap bevels are required for this hull shape, though gains must be cut at the bow and stern. The sheerstake was hung with the boat right-side up. “When it was dry-fit to my liking,” say Bill, “I followed a note on the drawing and twisted the aft end a bit to produce some tumblehome there. This looked good, so, again following Culler’s note, I cut a flat in the transom to receive the sheerstrake, then twisted 1 1/2″ over the 3′ from the last mold. It adds a nice bit of shape to the quarters.”

OTTER’s hull is fair. I got the chance to see the boat picked from its storage rack and launched, and can also vouch for the strength of Bill’s construction. It is a startling thing to see the boat, stern-to on the huge forklift with over half of its length hanging there unsupported, being trundled to the dock. These are demanding conditions, indeed. I also appreciate Bill’s efforts to remain loyal to the herringbone, or so-called “file” bottom planking, despite his need for a tight, glued construction. That bright planking inside the cabin just looks right.

“…shallow draft, impeccable manners off plane, and an imperceptible shift onto plane.”

Bill designed and built the cabin and interior, and got the proportions and details dead-on, to my eye. The only aesthetic complaint I can make is that the 115-hp engine appears a bit oversized to me. But that’s an aesthetic bias. Bill has a 15-mile commute in the boat, often with it heavily loaded. His feeling is that the extra speed he can get in the right conditions justifies the engine choice. In different circumstances, I think the boat would be perfectly happy with a 70-hp engine, maybe even less. That should be plenty to drive the boat on plane, and its proportions would be much better.

Reading Bill’s description of the construction and scantlings of OTTER, the reader will not be surprised to learn that this boat feels big, solid, and substantial on the water. She handles waves and chop well. Although like any planing hull she will slap in the right conditions, there is never any impression of fragility. The trade-off for that slight tendency to pound is shallow draft, impeccable manners off plane, and an imperceptible shift onto plane.

As a displacement boat, OTTER has a comfortable motion and good speed, and is easily controlled — even with the extra weight of that big motor. Cutting some of that excess weight in the stern would only improve the fine low-speed manners of the boat. Bill took her up to her 30-knot maximum speed for me, and while zipping through marshes was thrilling and I can certainly see the advantages of top speed on his long commute, I think I am most impressed with the boat just pooting around at idle. In my opinion, far too many powerboat designers seem to be completely unconcerned with the low-speed performance of their boats, while my experience leads me to believe that low speed is more important than top speed. Judging by OTTER’s behavior, I suspect Pete Culler felt the same.

The bays and estuaries of the east coast of Georgia are famous, or infamous, for oysters, strong tidal flows, and the tendency to develop a heavy, short, wicked chop in the right conditions. To be successful here, boats need shallow draft and fine entries. That Chesapeake style of bow with the thick staves planed to shape allows for a much sharper entry than sheet ply would, which let Culler leave the stem a little less raked, and improves the boat’s ability to breast that chop, especially running into the backs of the waves. She didn’t display any tendency to root or broach.

I’ve never spent any time on the Chesapeake Bay, but judging by how well Pete Culler’s design adapts to Bill Perkins’s stomping grounds, I’d suspect that the conditions there must be mighty similar to those in Georgia. In any event, the compromises that Culler chose to make in designing OTTER and those that Bill made in building her have resulted in a wonderfully successful marriage of boat and conditions. Bill still has his molds, and I got the distinct impression that he would love the opportunity to refine his methods, if there is anyone out there who feels the need for a similar set of compromises.

OTTER Particulars

R.D. "Pete" Culler

R.D. "Pete" CullerOTTER’s lines and cross-planked, or so-called file-bottom, construction are endemic to Chesapeake Bay; designer Culler popularized this form and construction technique in New England. This drawing shows Culler’s addition of a “Rhode Island box” shelter to the original design.

Plans for this launch — and other designs by Capt. Pete Culler — are available from Mystic Seaport, 75 Greenmanville Ave., P.O. Box 6000, Mystic, CT 06355–0990; 860–572–5315

Check Out More Pete Culler Designs

You can find a Boat Profile on a Pete Culler designed sailing skiff here.

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.