I was sitting in the cabin of the Escargot canal cruiser BONZO, a boat my son, Nate, and his friend Bobby Calnan built the summer after they’d graduated from high school. It was a winter evening—cold and dark outside—but I had a fire going in the woodstove and a few candles lit. I heard a knocking on the hull and opened the door to find a woman peering over the transom. “Hi,” she said, “I just wanted to say how much I love your boat.” I invited her to come aboard and she climbed over the transom, a bit awkwardly because she was wearing a long skirt and fashionable leather boots with high heels. I couldn’t fault her for her attire because she’d just gotten off the bus on her way home from work. BONZO was on the trailer, high and dry in my driveway.

Photographs and video by the author

Photographs and video by the authorAfter spending a quiet and cozy night with BONZO aground on a gravel bar, Nate tidies the forward sleeping quarters while his sister, Alison, does the dishes. The rising tide floated BONZO for the downstream home stretch on the Snohomish River.

As a wooden boat, the Escargot is an unlikely charmer. It has a hull like a shoebox, only two curves to speak of, and is entirely bereft of brightwork and brass. Nonetheless, it has an ineluctable appeal inside and out. The cabin with its arched roof and stovepipe has the look of a gypsy wagon and the lure of running away from it all, in comfort. My father said of it: “The moment I step aboard, I’ve arrived.”

The cabin and the forward berths are separated by small bays for the head (left) and the wood stove (right).

The Escargot, like many of the small boats designed by the late Phil Thiel, is meant to foster the ideals of what the French called a flaneur. Charles Baudelaire described the flaneur as the “passionate spectator” for whom “it is an immense joy…to be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the center of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world.” The Escargot steers us in that direction. As a “flaneur afloat” Phil aimed to “savor the shore-side pleasures at the ideal rate of speed—slowly. The faster you go through the environment the less you can enjoy it. At slower speeds the world around you reveals itself on a smaller, more human scale.”

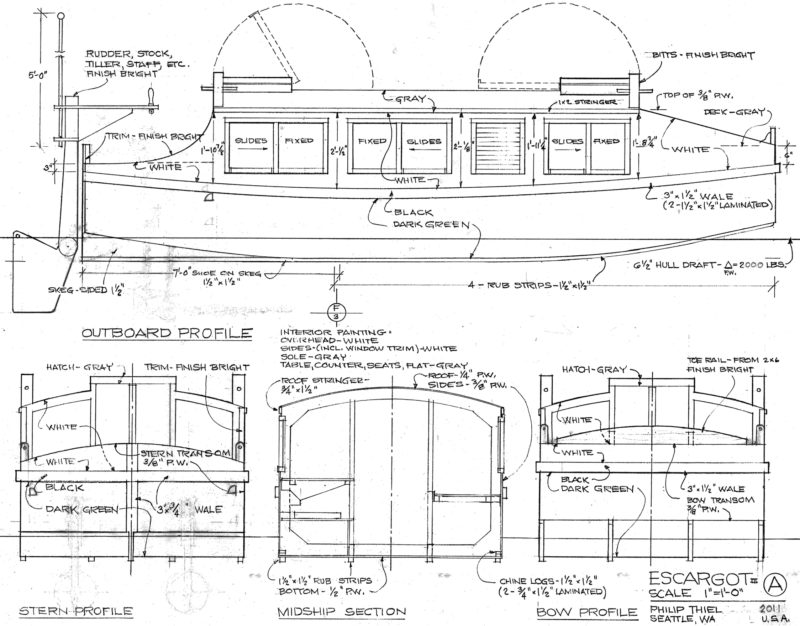

Let’s get the Escargot afloat. Phil intended her for “use limited to sheltered inland waterways.” The canals he frequently traveled in France were his inspiration, and similar narrow waters free of wind and waves are where the Escargot performs most admirably. The barge-like hull is an 18′ 6″ by 6′ rectangle. The flat bottom meets the bow transom 6″ above the waterline and the stern transom just even with it. The cabin is 11′6″ long and divided into three sections: a cabin with a galley and a dinette/berth, twin berths partially tucked under the foredeck, and a 2′ bay in between for the head and a hanging locker. The foredeck and the cockpit are both about 3-1/2′ long.

In thin water it’s time to kick up the motor, stow the oars and haul the Escargot on foot.

Phil calculated the weight of the bare boat at 750 lbs; displacing 2,000 lbs, the Escargot will draw only 6″. Nate and I have pulled BONZO across shallows scarcely more than ankle deep. As you’d expect, the barge-like hull has exceptional stability. I have yet to ask passengers to shift their weight to trim the boat.

The Escargot is not a petite boat but its shallow draft gets it into some small waterways. Standing in a forward hatch, Nate explores a backwater frequented by beavers but not by boats.

We don’t have canals in the Puget Sound area, but there are a number of narrow sloughs where the rivers take their sweet time crossing the flatlands between the foothills and the Sound. Here the Escargot is quite at home: the water slips quietly under the bow and curdles up astern.

We’ve taken BONZO out on the local lakes and on the wide salt water of Puget Sound, and have had a few run-ins with wind and waves. In a bit of chop the bow transom will begin shaving the tops off the waves, and in anything much over 12″ high it will throw up some spray. The cockpit is far from the fuss and protected by the cabin, so it’s a good refuge for the helmsman. With only a 2.5-hp for power, BONZO carries enough momentum to keep moving forward through the waves we get in the lakes we frequent.

The kick-up rudder coaxes the Escargot through turns; steering with the outboard makes her much more maneuverable in tight quarters. While underway in a crosswind there’s enough steerage with the rudder to hold a course, but when idle, the bow will slip downwind. I’ve thought that a slot in one of the rub strips would make it easy to slip a daggerboard alongside the foredeck; it would resist the downwind drift of the bow and give the hull a point to pivot around.

Phil had originally designed the first two versions of the Escargot to be driven by a pair of SeaCycle pedal drives: “This pied-à-l’eau approach was, and remains the ideal. However, the pedal-drive unit I proposed using was not suitable for slow speeds and heavy loads.” SeaCycle’s drives are designed for light, easily driven catamaran the company makes, the largest of their boats being only 14′10″, 175 lbs, and capable of 12.8 mph. The pitch of SeaCycle propellers is not well suited to a boat the size, weight, and speed of the Escargot and couldn’t be pedaled at a comfortable cadence. (There are some Escargots in Germany that use pedal drives, but they’ve been outfitted with custom-made props.) The Escargot plans available now call for a 2- to 5-hp outboard. BONZO is powered by a 2.5-hp, four-stroke outboard that’ll get us up to about 4.5 knots.

The cockpit of SHAMBALA is built according to the plans. Builder Bryan Lowe omitted the hinged hatch over the companionway on the aft end of the cabin roof, but kept the one over the smaller passageway forward. Bryan steers SHAMBALA with his outboard. BONZO was ultimately outfitted and steered with the rudder drawn in the plans.

Building an Escargot Canal Cruiser

There are a few modifications we’ve made to the design. Our first experience with the design was aboard Bryan Lowe’s SHAMBALA, and we followed his lead and added 6″ to the height of the cabin sides. It’s a bit more complex than working with the standard 48″ width of plywood sheets and adds to the windage, but the extra headroom is a better fit for tall passengers. Bryan’s cockpit, built to the plans, felt a bit confined, so we lengthened BONZO’s by 12″. The easiest way to do that was to add the length to the flat part of the bottom to shift the aft third of the hull out past the cabin wall. We have more elbowroom for starting the motor and sharing the space with passengers.

The catwalk added to the cabin roof proved to be a popular perch aboard BONZO. The bow often allows stepping ashore with dry feet, though in this case, with very muddy boots.

Nate wanted a catwalk on the roof to use as a runway that he and his friends could use for diving on summer outings. It turned out to be a very pleasant place to sit with a commanding view, and it saved Nate and Bobby from making the hatches over the companionways.

Christened, launched, but not quite finished, BONZO experiments with oar power. With the cabin obscuring vision between oarsmen, synchronizing was difficult.

We added oarlocks at both ends of the boat and hatches on the foredeck to create footwells for the bow oarsmen. Rowing was a nod toward a human-power ideal we share with Phil, but ultimately it proved impractical for covering long distances. Even if we could get four oarsmen, the bow rowers couldn’t see the oars of the stern rowers and couldn’t row in synch with them. The hatches turned out to be useful for stargazing from the forward berths.

With the roof an extra 6″ higher, the main cabin has plenty of headroom and an open, airy feel.

The galley Phil designed for the main cabin has a built-in sink and a recess for a stove to starboard. Nate didn’t anticipate needing a permanent galley and opted to put seats on both sides so he could have a fourth berth. Large plexiglass windows in all of the cabin compartments let in plenty of light, provide expansive views, and, when open, a cooling breeze. The hanging locker was converted to make a space for a small homemade wood stove.

The number of modifications we made isn’t an indication that the design lacking in any way, but that it is easily adaptable to suit the needs of the builder. With so many straight lines and right angles, it’s very easy to shift things around for personal preference.

The Escargot is initially assembled upside down. Uprights on the transoms and bulkheads extend to a baseline to align them. After they are secured to the sides and the bottom, the extra length is sawn away.

The plans are exceptionally well detailed, covering every element of construction from the cutting schedule for the 23 sheets of plywood to the drain slots on the window molding. There won’t be much head scratching in the building, even for novice woodworkers. The instructions specify marine-grade plywood. We used marine-grade fir plywood for BONZO. It used to be pretty good stuff, but I’d steer clear of it now. Mahogany BS 1088 plywood costs more but has fewer defects, is easier to work with, and lasts longer.

Materials for BONZO cost about $4,000 in 2009. We didn’t keep a log of hours, but Nate and Bobby poked along through the summer and put on a big push, working nearly full-time in September to get her ready to launch before cold, wet weather set in.

Nate and his friends often take summer weekend cruises in BONZO. For myself there are two times each year when I especially like to be aboard: to celebrate my birthday and to do my taxes. It is (with apologies to Charles Dickens) the place to be in the best of times and in the worst of times.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small boats Monthly.

Escargot Particulars

LOA: 18′ 6″

Beam: 6′

Draft: 6″

Bare Hull: 750 lbs

Recommended outboard engine: 2–5 hp

Print and digital plans, at $75, are available from the WoodenBoat Store.

Be sure to read our design review of the Escargot before you build.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

I like the idea of raising the cabin height but wouldn’t a celestory window the length of the cabin achieve the same thing?

That’s certainly a possibility. The cabin is quite brightly lit with the windows it has—too bright on those summer mornings when you’d rather not get up with the sun. Consider curtains for any windows you put in.

I love it! Thanks for the great read and the inspiration.

I’ve been scheming of a similar design, something between this and Harry Bryan’s Shantyboat.

I worry about the amount of slapping at anchor in a bit of chop. Has this been an issue for you?

As you might expect the hull is quite resonant. The noisiest waves are those that slip under the overhang at the bow and make contact on a broad area all at once.(If waves are high enough to hit the bow transom, you may have the wrong anchorage.) I’ve mused about ways to get quieter nights: making the anchor rode fast to a bit on the corner, putting sound-dampening cargo under the forward sleeping platform, stringing a line of fenders under the bow—but haven’t tried any of them yet. In the “sheltered inland waters” Phil designed the boat for, we’ve always been able to find small, quiet coves. The nosiest nights are those Nate has had when he has anchored in Anderson Bay on Lake Washington. It’s the only place in the Seattle City Limits where you can legally anchor and the bay is open to the north.

Great article. We are actually building one of Phil’s boats ourselves now. Not the Escargot but the Joliboat, (a larger version: Length 22’9″, Beam 8′, Draft 9″). You can see progress at our photo album. Our plan is to launch her next summer.

For another neat small houseboat I’d suggest DIANE’S ROSE. featured in Small Boats 2015 and on YouTube.

I have been quite taken with this rather attractive design as a great holiday boat on our River Murray where house-boats abound in huge numbers and many sizes. The problem here is that in the quieter and shallower reaches of the Murray there are submerged trees and stumps, which cannot be removed as they provide habitat for the Murray Cod. It appear that the Escargot has a 1/2″ plywood bottom, which concerns me a little.

Hitting one of these trees might penetrate the hull. I was wondering how an extra sheet laid over rub strips might affect the performance.

The curves on the bottom are not so tight that you couldn’t use thicker plywood on the bottom. Adding fiberglass would further increase the resistance to damage by submerged stumps.

Gorgeous design, do you think the hull could be sail powered? Perhaps with pivoting leeboard and either a balanced lug or lateen sail.

A square sail is the only one we’ve tried and it works very well for making relaxed and quiet downwind runs. I put fittings on the forward end of the cockpit, just to the port side of the door, to support a mast from one of our other boats. That’s as far as we’re likely to carry that experiment. You could put a sail and a leeboard on an Escargot, but if sailing is a priority you might look for a similar design with some concessions made for sailing performance. A few worth taking a look at are the Jewelbox, the Superbrick, and the Triloboat.

Hi Jeroen,

Exciting to see the Joliboat is under construction! Let me know when it’s finished. I would love to come over from Munich to see it!

Take care, Tamiko (Phil Thiel’s daughter)

Hi Tamiko,

Just read your reply! You are more then welcome. The project was on hold for two months because we had to wait for space on the building site. Plan is to erect the frames this summer.

Might be a dumb question, but does it really matter that much if you don’t row in sync as long as the oars don’t hit each other?

It’s not at all a dumb question. When a crew is rowing any boat, whether it’s as heavy as an Escargot or as light as a racing shell, the greatest load comes on the rower at the catch. If the crew is in sync, the load is divided evenly by the number of rowers. If the crew is out of sync, the first oar in the water will feel the entire combined weight of boat and crew. In theory, the load on the rowers could be equally distributed if each made the catch at even intervals, but then that requires as much coordination, if not more, as rowing in sync.